‘Making a contemporary weave is like planting a seed into a new, uncultivated field. When the seed sprouts, the resulting fabric is a fruit which communicates with all our senses and makes us rejoice.’

- Junichi Arai

The National Library collection of Japanese textile sample books includes examples from old to new: from replicas of imperial fabrics from a thousand years ago, sample collections from the 19th century, sales sample books from a century ago, regional samples collected in the 1970s; and many others.

The National Library collects these sample books due to the importance that the Japanese Unit of the Overseas Collections Branch has attached to the “Mingei Movement” which was developed in the late 1920s and 1930s in Japan, founded by Muneyoshi Yanagi. The Mingei movement was an art movement which tried to discover and introduce the beauty of Japanese folk art and craft to a larger audience, not dissimilar to the British Arts and Crafts movement of the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

There are many ways to study these sample books. You could research the history of the Silk Road and how techniques arrived in or were reverse engineered in Japan. You could research the different structures, designs, dyes, materials, purpose, of the cloths, while considering the influences from society, dynastic change, historical technological development, market force and regulated economics. You could consider the anthropology of weaving communities, how they interact in cities and rural areas, and the influences of seasonal changes.

Having a background in textiles, I have found it very difficult to focus on one element of these textiles, but for the moment at least, I have been focusing on the sample books with some documentation about the fabrics.

I know first-hand the value of learning from sample books - a lot of my early weaving development came from a set of industrial weaver’s sample record books from the 1920s. They are technically rigorous, aesthetically beautiful and demonstrated a snapshot of early Australian textile design production. These books became personal; it was much more of a conversation with a weaving mentor from nearly a century ago. The answers were in the books, you just needed to find your own way to ask questions.

My research so far in the Library collection has been concentrated on samples mostly from Japanese Traditional Woven Fabric., a snapshot of 150 woven samples mounted on washi paper, compiled in 1975. Aside from the impressive volume of samples, the collector has thoughtfully noted the type of fabric, content, weaver and location - this information is seldom recorded. Adding to this unusual information is a second volume containing detailed accounts of exactly how each fabric was produced, including photographs of harvesting the fibre, processing, weaving and finishing the fabric. At a limited edition of 750 copies, this collection is a rarity, as well as an invaluable resource to weavers and historians alike.

Woven Structure

The first thing a weaver can learn from sample books is basic structure - a thread goes either under or over another perpendicular thread. Plain, tabby or hiro-ori is the strongest, sturdiest and simplest weave structure. The sample below demonstrates how simple colour changes are used effectively in plain weave.

Sample on page 25, Nihon dentō orimoto. shūsei (Traditional Japanese Woven Fabric), compiled by Kirshiro Tatsuai, 1975, nla.cat-vn6489327, nla.cat-vn6489327.

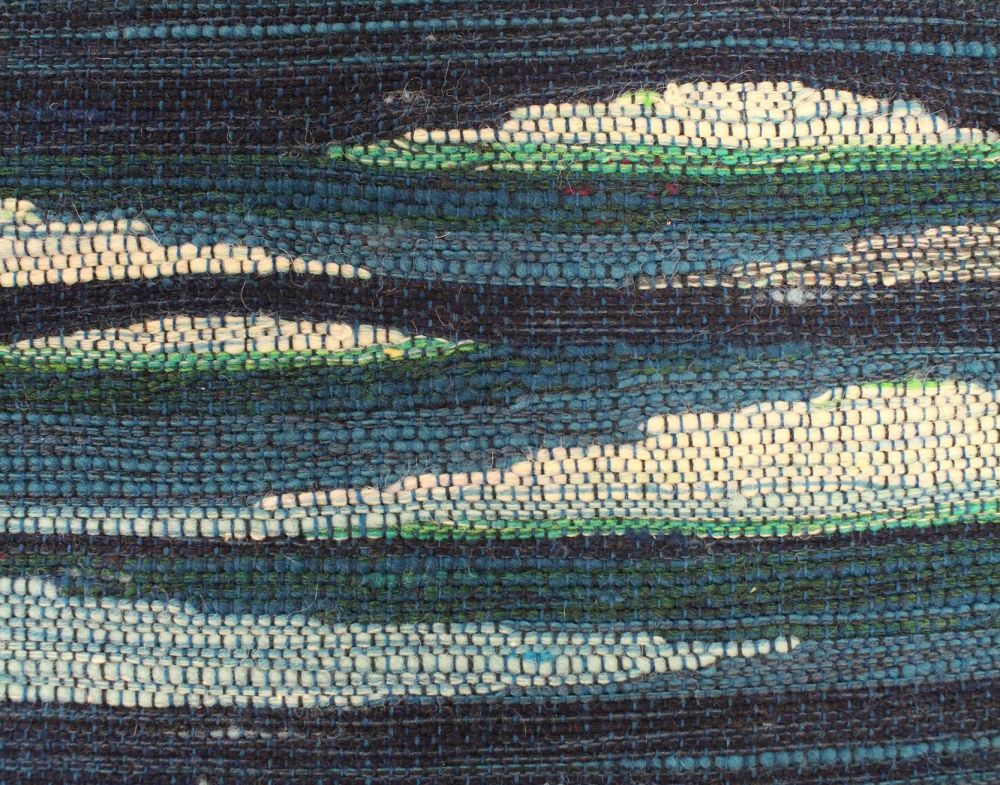

After you are comfortable with plain weave, you might notice that a thread moves in a different way, going under two or three threads instead of one, making a different pattern. In the image below, the dense blocks (like a checkerboard) are created by the darker weft threads skipping over several warp threads, creating denser blocks of colour (the warp and weft alternate with light and dark threads; the reverse has the light wefts skipping over the same areas).

Sample on page 123, Nihon dentō orimoto shūsei (Traditional Japanese Woven Fabric), compiled by Kirshiro Tatsuai, 1975, nla.cat-vn6489327, nla.cat-vn6489327

Sample on page 123, Nihon dentō orimoto shūsei (Traditional Japanese Woven Fabric), compiled by Kirshiro Tatsuai, 1975, nla.cat-vn6489327, nla.cat-vn6489327

Or you might wonder how this pattern below is created so precisely using plain weave and specially dyed threads. You can spend several lifetimes learning and practising kasuri or ikat weaving from different parts of the world. The threads are tied and dyed in a pattern before they are woven on a loom. The slight misalignment that occurs when woven creates a beautiful blurring effect.

Nihon dentō orimoto shūsei (Traditional Japanese Woven Fabric), compiled by Kirshiro Tatsuai, 1975, nla.cat-vn6489327, nla.cat-vn6489327

Materials

While it is quite common to find Japanese cloth made from silk, cotton and hemp, there is a wide variety of plant fibres to experience through the sample books. Banana, ramie (from the nettle family), bamboo, bark, paper and what is becoming my favourite rarity, fern silk from the tiny fiddlehead of osmunda japonica. Tiny, fluffy fibres are harvested from newly emerged fern fronds and spun into thread. The sample below is from the Yamagata Prefecture and demonstrates the resulting texture.

Sample on page 101, Nihon dentō orimoto shūsei (Traditional Japanese Woven Fabric), compiled by Kirshiro Tatsuai, 1975, nla.cat-vn6489327, nla.cat-vn6489327.

Design

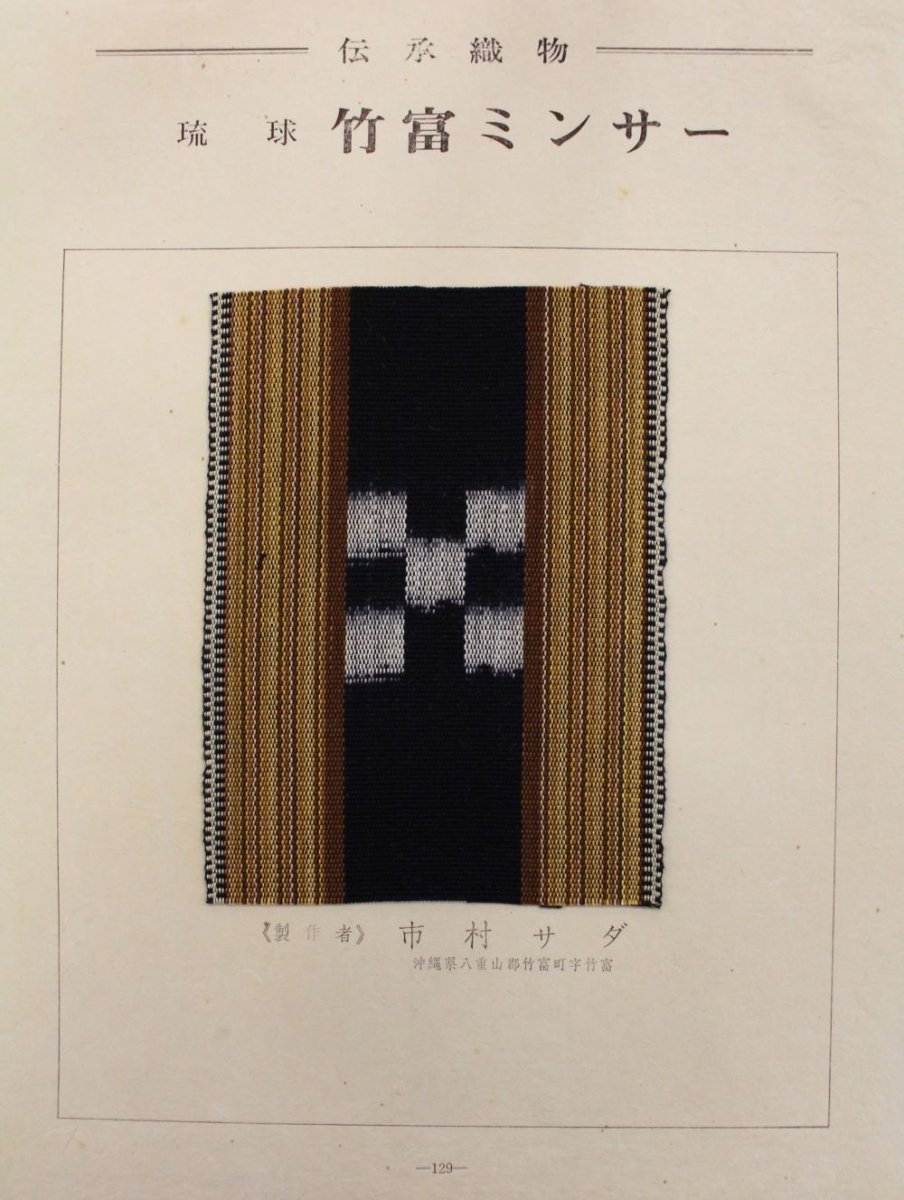

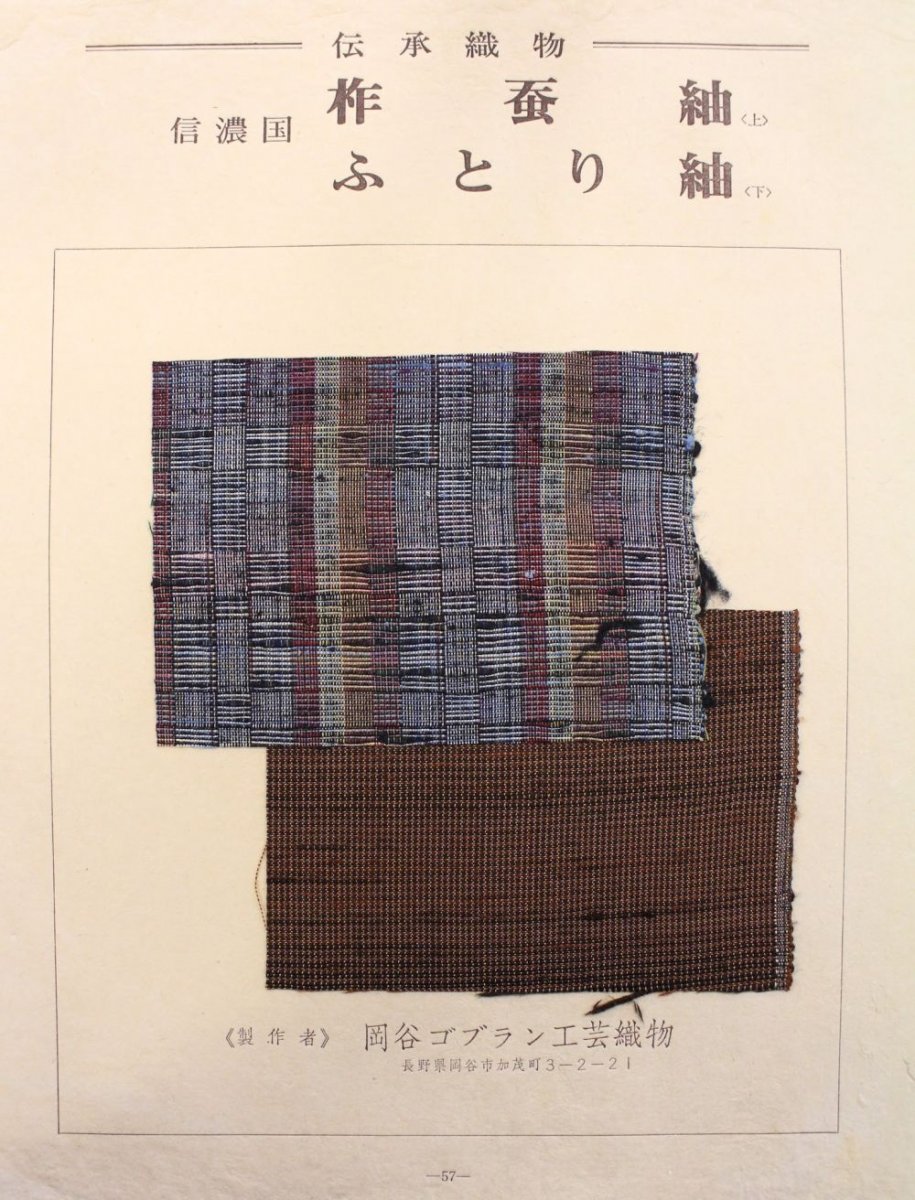

The Japanese sample books vary wildly in design, as the purpose of each book is different, if only slightly in some cases. The designs for the fabrics of monks, you would expect to be significantly different from the rough durability needed for everyday workwear. Regionally, as is beautifully recorded in Japanese Traditional Woven Fabric, the differences are carefully noted. Note the differences between the first example below from a maker in Okinawa and the second from a workshop in Nagano Prefecture.

Page 129, Nihon dentō orimoto shūsei (Traditional Japanese Woven Fabric), compiled by Kirshiro Tatsuai, 1975, nla.cat-vn6489327, nla.cat-vn6489327.

The sample produced in Taketomi Island, Okinawa is a detail from a narrow but long (approx 2.3m) kimono sash called a ‘minsa’. The design is said to derive from the Ryukyu Era, around 400 years ago. You can recognise these quite easily from the design in which five squares are quickly followed by the opposite 4 squares, which is associated with a saying ‘Itsu (sounds like the Japanese for five) yo (sounds like four) mademo’ - ‘Love me forever’, or similar sayings. If you look closely, you can also see a comb-like pattern on the edges called ‘Yashimari’ which should indicate that a women wishes the recipient to visit her frequently. Thanks to the unusual detail of this sample book, we know that the weaver was Ichimura Sada.

Sample on page 57, Nihon dentō orimoto shūsei (Traditional Japanese Woven Fabric), compiled by Kirshiro Tatsuai, 1975, nla.cat-vn6489327, nla.cat-vn6489327

Eventually, you come to know and understand the weaver and realise the choice that was made at that moment. It’s exciting to realise that a person held this piece of fabric when it was merely threads. Suddenly you’re connected to a person who constructed a piece of fabric thirty, forty or several hundred years ago.

Sample on page 120, Nihon dentō orimoto shūsei (Traditional Japanese Woven Fabric), compiled by Kirshiro Tatsuai, 1975, nla.cat-vn6489327, nla.cat-vn6489327

Join us for an opportunity to get up close with this sample book and other hidden textile treasures in the Library's Asian collections at the Friends White Gloves: Asian Textiles event at 6pm, 9 April 2019.

With grateful thanks to Belinda Jessup for asking the right question, Haji Oh for several translations and explanations, and to the wonderful staff in the Asian Collections Reading Room at the National Library of Australia.