National Library of Australia Fellowships provide an opportunity for researchers to explore the Library’s collection, blissfully uninterrupted, for up to 12 weeks.

Dr Kama Maclean is Associate Professor of South Asian and World History at the University of New South Wales, and is a 2019 National Library of Australia Fellow supported by the Harold S. Williams Trust. Her Fellowship presentation, R.G. Casey, the Bengal Famine and Australia-India Relations was delivered on 29 August 2019.

Associate Professor Maclean’s research examines the life of statesman Richard Gavin Gardiner Casey (R.G. Casey) during his governorship of Bengal, India from 1944 until 1946. His governorship was a short, wartime appointment in a province troubled by famine, the threat of invasion, and rising communalism prior to its partition in 1947. Drawing on the diaries of Casey and his wife Maie, Associate Professor Maclean considers Casey's attempts to ameliorate the effects of famine, which included working with Australian civil society organisations who lobbied to raise funds for famine relief.

In this blog, Associate Professor Maclean explores the effect of R.G. Casey’s spouse, Maie Casey, during his tenure in Bengal. She writes:

My project at the NLA was to focus on the impact and significance of R.G. Casey’s Governorship of Bengal from 1944-1946. No existing biography of the Caseys, Dick or Maie, particularly deftly deals with this part of their lives; it was, after all, a short two-year appointment. But Casey held the role at a critical time for the Indian province, on the frontline of war, and in the grip of a devastating famine that would kill an estimated three million people.

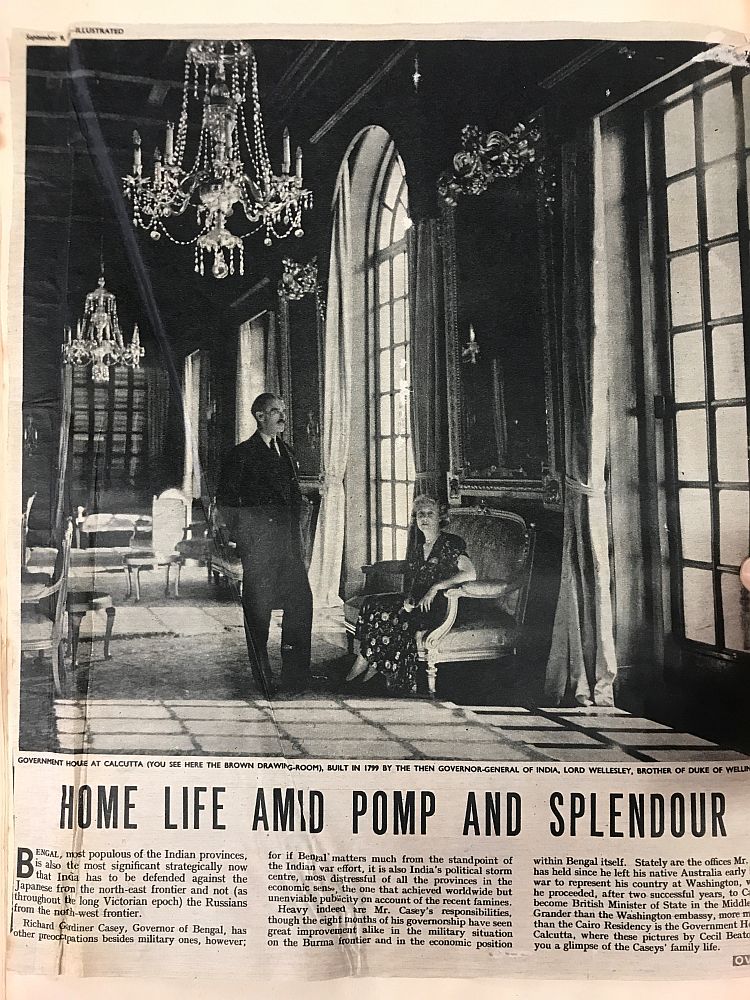

In correspondence between the Viceroy and Secretary of State for India it is evident that one of the unwritten criteria for appointment to the role of Governor of Bengal, a high-status Presidency, was the suitability of the candidate’s wife. Maie fit the bill. She was described in the press at the time as ‘a great asset to her husband in public life’. She was in many ways very unconventional: like Dick, she was a capable aviator, who personally flew her children, Jane and Donn, to their boarding school in Nainital; and she was a woman with formidable organisational skills.

Image 1. The Caseys in Government House, Calcutta, the original Viceregal Palace, built in 1799. Illustrated (London), September 8, 1944. Papers of the Casey family, 1820-1978, Series 5, Box 40, nla.cat-vn2896954

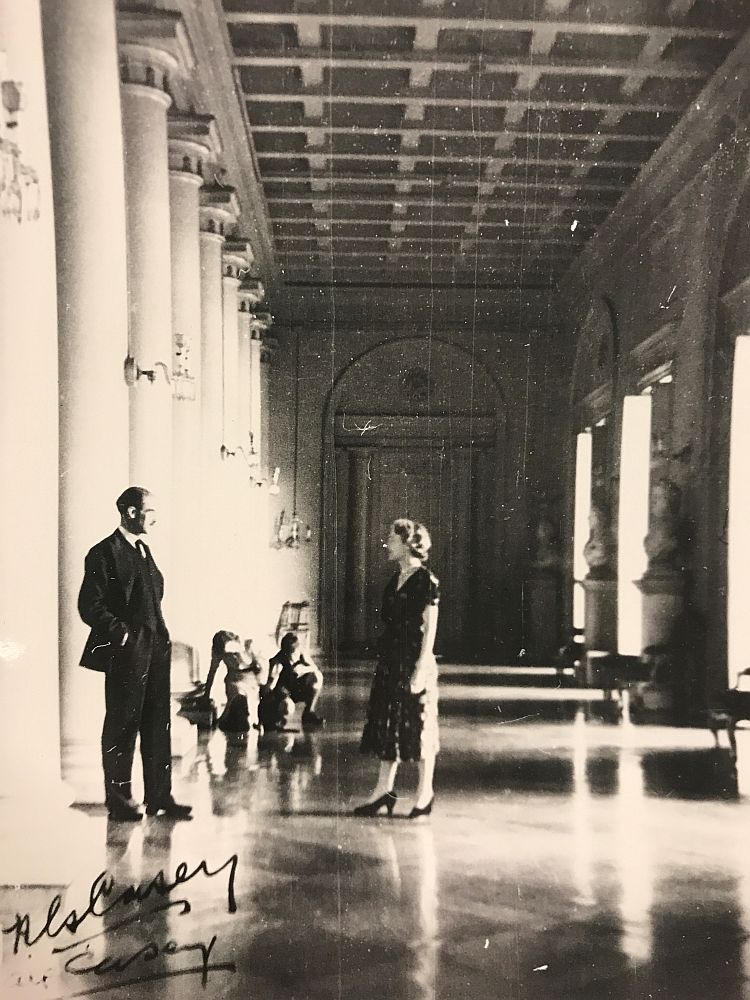

The Caseys had a very good understanding of the importance of positive media coverage, engaging Pat Jarrett, a friend and confidante, as their press secretary. An experienced journalist herself, Jarrett excelled at feeding the Australian media with a steady diet of press releases and photographs. The Caseys were projected in the Australian and even in the British press as a handsome power couple (Image 1). It did not hurt, either, that they were close friends with Cecil Beaton, who photographed them extensively during their time in Calcutta (Image 2, 3).

Image 2. R.G. Casey with wife Maie and children Donn and Jane in Calcultta, 1944 trove.nla.gov.au/work/33574995

Image 3. A signed portrait of R. G. And Maie Casey, by Cecil Beaton. Papers of Frank Clune, ca. 1930-1992, Series 4, Box 222, nla.cat-vn2631836

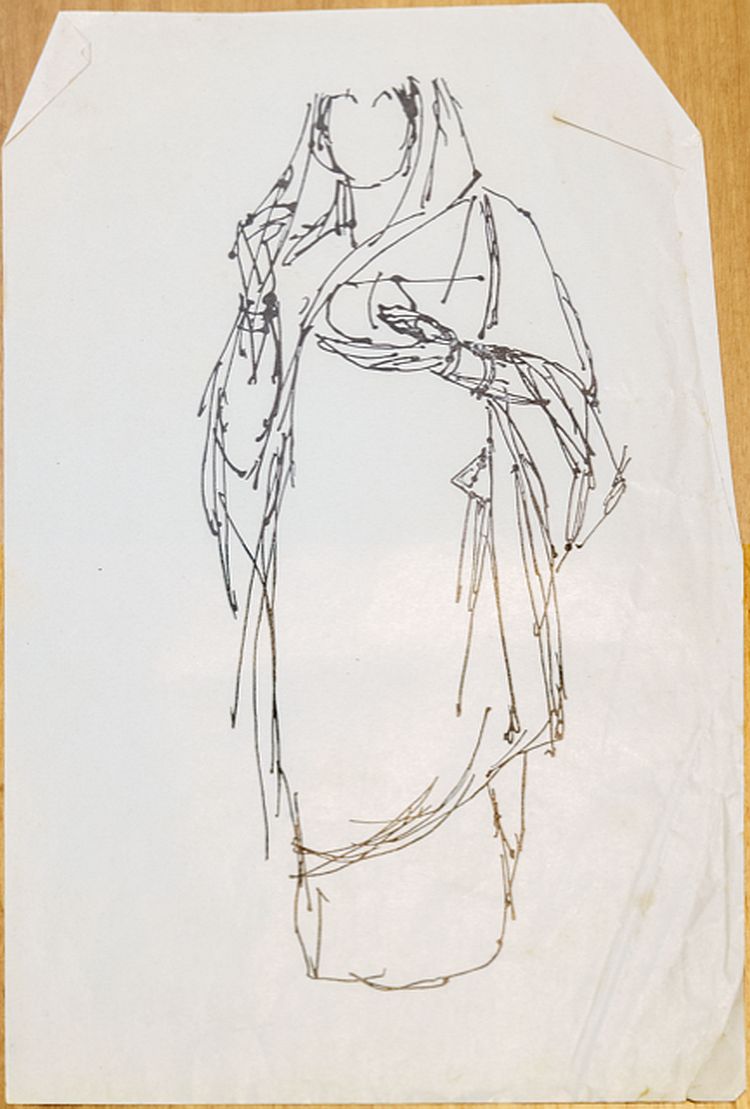

Not long after her arrival in Calcutta Maie wrote to a friend in New York, Elizabeth Hudson, that ‘as far as art goes, I feel rather starved’ (1). Art was one of her life-long passions. It did not take long for her to seek out one of Bengal’s most famous contemporary artists. Within weeks of arriving, she had met Jamini Roy (1887-1972), an eminent modern artist of the Calcutta Group whose distinctively minimalistic style eschewed Western realism. Casey notes in his diary, on Jan 26, 1944: 'Donn apparently had quite a success today with a painter called Jamini Roy – a caste Hindu. They exchanged drawings’ (2). The sketch Roy gave Donn is kept in Maie’s papers (Image 4), along with letters Roy sent to Maie, which indicate that he sent coloured paints for Donn and Jane with the encouragement that they both keep painting, and to visit him again soon (3).

Image 4. The sketch Roy gave Donn, Papers of Maie Casey, 1821-1987, nla.cat-vn2997181

In 1945, Maie organised an exhibition of Bengali art in the ground floor of Government House (Image 5). This was unprecedented, as Pat Jarrett recalled: ‘the official people on the staff at Government House were horrified at the thought of Bengalis wandering through Government House looking at an art exhibition!’ But Maie proceeded, ignoring their protests and the exhibition ‘went off without any trouble at all’ (4). An editorial in the Statesman commented that the act of ‘throwing open the solemn precincts of Government House’ to the public was perhaps more significant than the exhibition itself (5).

Image 5: Maie Casey poses with artists at the Exhibition of Bengali Art, Government House, April 1945. Papers of Maie Casey, 1821-1987, Box 21, nla.cat-vn2997181

The exhibition was praised in the Amrita Bazaar Patrika as a rare and ‘happy hour of official appreciation of the original qualities of Vernacular art of Bengal’ (6). News of the exhibition reached Australia, with the Art Galleries of New South Wales and Victoria writing to Maie to have the exhibition tour Sydney and Melbourne (7). In the context of the war, however, shipping the artefacts, some of which were large stone sculptures, turned out to be difficult to arrange.

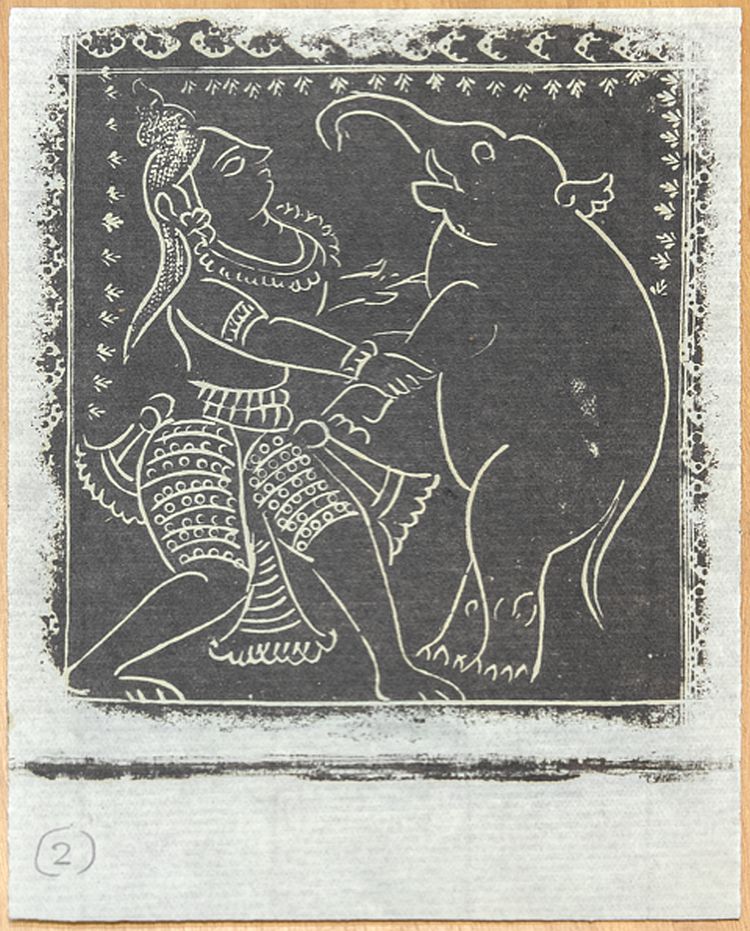

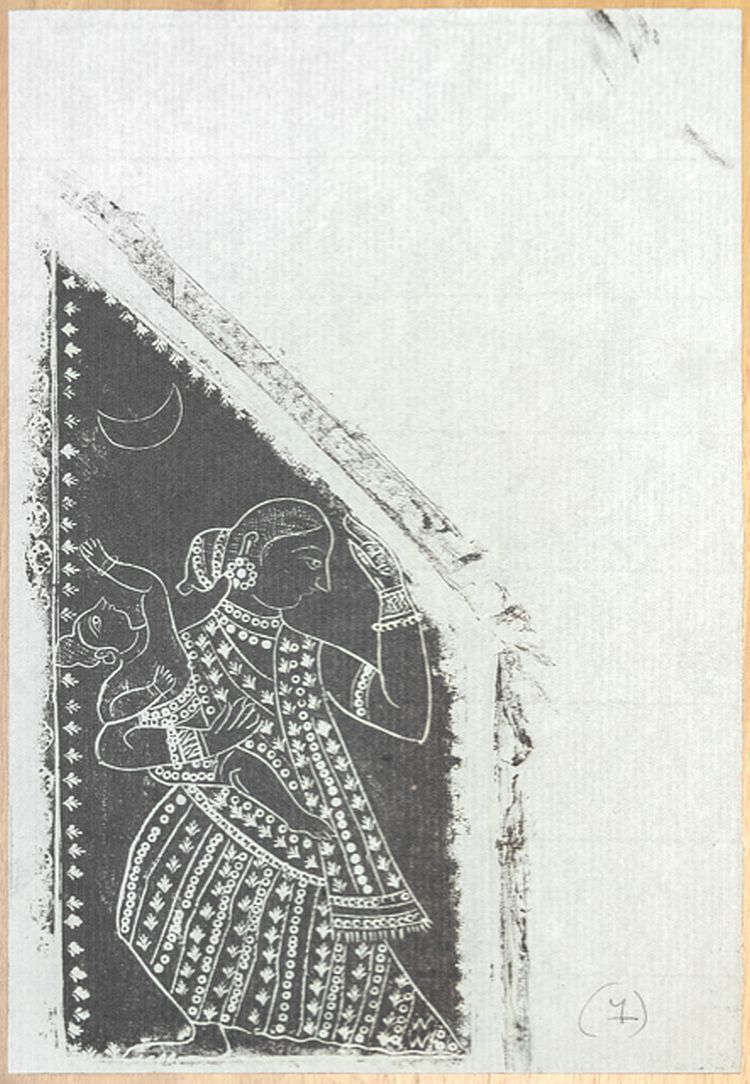

Maie Casey’s papers hold an extraordinary collection of rubbings taken from brass engravings from a 200-year old chariot from Baukathi, in the district of Burdwan. The 18 rubbings, representing scenes from the life of the god Krishna, are well preserved (Images 6, 7). Maie also took a great interest in Bengali folk arts, and published a book on Alpona, a traditional form of decoration done by women using rice flour. As the Caseys were preparing to leave Calcutta, Maie wrote to a friend saying how much she would miss India: ‘like Dick, I am sorry to leave. But one only has one life and we are very fond of Australia and anxious to be of service there’ (8).

Image 6: Krishna fighting with an elephant. Papers of Maie Casey, 1821-1987, Box 21, nla.cat-vn2997181

Image 7: A gopi with her son, looking at the moon. Papers of Maie Casey, 1821-1987, Box 21, nla.cat-vn2997181

Maie’s papers reveal the importance of her work in supporting Casey in Calcutta. More importantly though, they indicate her interest in and engagement with the world of Indian art, appreciating and celebrating its uniqueness.

Kama Maclean is Associate Professor of South Asian and World History at the University of New South Wales.

(1) Maie Casey to Elizabeth Hudson, 26 March, 1944. Papers of Maie Casey, 1831-1987, MS 1840/1/77, nla.cat-vn2997181

(2) 26 January, 1944, Papers of the Casey family, 1820-1978. MS 6150/4/6, pg 52, nla.cat-vn2896954

(3) Jamini Roy to Maie Casey, 4 April, 1944. Papers of Maie Casey, 1831-1987, MS 1840/4/6, Box 21 nla.cat-vn2997181

(4) Jarrett, Pat & Cranfield, Mark (1984). Interview with Pat Jarrett, journalist. nla.obj-202244707/listen

(5) 'An Exhibition of Bengal Art’, Statesman, 29 April, 1945

(6) ‘Exhibition of Bengal Art’, Amrita Bazaar Patrika, 1 May, 1945. Papers of Maie Casey, 1831-1987, MS 1840/4/2, Box 21, nla.cat-vn2997181

(7) ‘Plan to lend Indian art collection’, Herald, 5 January, 1945. Papers of Maie Casey, 1831-1987, MS 1840/5, Box 41, nla.cat-vn2997181

(8) Maie Casey to J.R. Bryans, 12 December, 1945. Papers of Maie Casey, 1831-1987, MS 1840/1/76, Box 10, nla.cat-vn2997181