Been indulging in too many Covid snacks lately? Take some Turkey Rhubarb! 10 weeks of ‘iso’ brought you to ‘lowness of spirits’? Try Spirit of Sal Volatile! Had you been languishing in Ballarat, Victoria, in the 1850s, these are two of the remedies that probably would have been dispensed to you by Mr George Wakefield.

As my own antidote to lockdown languishing, I have been transcribing one of the Library’s digitised manuscript collection, MS 684, comprising 32 letters from newly arrived immigrant, George Wakefield, written around the 1850s from Ballarat and Kerang, to his family back in England.

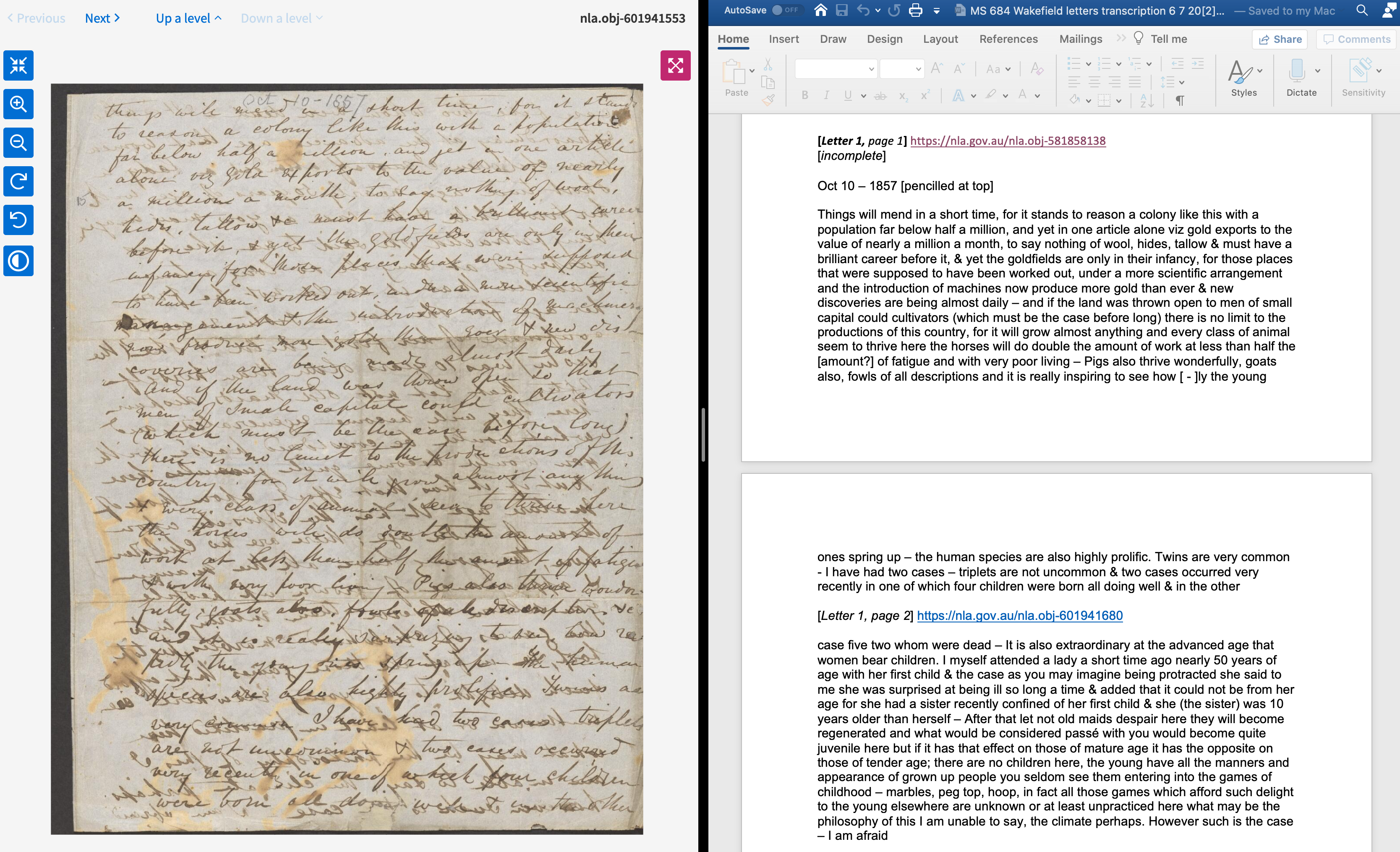

Left: MS 684 Papers of George Wakefield 1853-1887; Right: Clare Cruickshank's Transcription, 2020.

The Academy of Science believes George was a medical practitioner who ‘flourished’ between 1853 and 1888. From his letters, we learn he was a doctor with his own dispensary. George’s first letters after arrival describe his attempts to find a suitable shop and he complains about exorbitant rent prices (plus ça change). Others include requests for a variety of dispensing labels and mentions of ‘a chemist’s shop’.

Transcribing colonial letters brings many challenges—decomposition (as it were), untidy handwriting, unfamiliar formal language, abbreviations and terms, and ink bleed through. So I was perplexed but not surprised to be faced with entire lines of apparent gobbledygook at the end of the first letter to his father, dated 10 October 1857. George’s correspondence tends to follow a pattern: an account of his personal circumstances, a litany of complaints about colonial society, ending with a shopping list of supplies his father is to send. Chemists, then as now, place labels with their own name and address on each bottle. George details the range of ‘dispensing lables’ he requires—which is where I got stuck. Can that really say ‘Turkey Rhubarb’? ‘Ess Pep’? ‘Sp.Ntre’? Is that word ‘Opoldeldoc’? Has the man had a stroke? Or could this be one occasion when it is permissible to consult Dr Google?

At this point I had two strokes myself (of luck). One is living with a medical historian who recognised ‘Ess Pep’ as Essence of Peppermint, for treating wind. The second was a breadcrumb trail leading to an article about the Faithfull family collection in reCollections, the NMA’s erstwhile online journal. The Faithfulls came from Springfield, near Goulburn, and their extensive collection was split between the National Library (papers) and the National Museum (objects). The article explored the medicine chest of Dr Robert Faithfull and, fortunately for me, outlined its contents (pictured below) and his instructions for their use, relayed below.

Some of the contents of the Faithfull family collection medicine chest, National Museum of Australia.

George’s illegible scrawl gradually swam into focus as I correlated the chest’s contents with his letter. Dad was to send bottle labels for:

- Essence of Peppermint, Essence of Lemons (for wind);

- Paregoric, a delicious tincture of opium, benzoic acid, camphor and anise oil;

- Sweet Spirit of Nitre, ‘for relief in suppression and heat of urine, particularly in the scalding arising from gonorrhoea, or clap’;

- Turkey Rhubarb for ‘indigestion from crudities, cholic, gripings, and pains in the bowels’;

- Best Jalap, a purgative used to induce vomiting;

- Opodeldoc, a plaster or liniment;

- Spirit of Sal Volatile, a restorative in fainting or low mood;

- Purified Epsom salts;

- Seidlitz Powder and aperient (laxative) pills.

Once decoded, George’s list provides a valuable illustration of the history of medicine and treatment in colonial Australia. But there its utility ends. None of these treatments they believed beneficial are used today. Some are harmful, others useless. The number of purgative medicines (for both ends) underlies the belief going back to Roman times, of illness being the result of imbalance in the body’s humours. So the approach was to purge the body of unwanted elements in order to restore balance. Although germ theory was beginning to be understood in Europe around the time of Wakefield’s letters, its spread to the colonies lay in the future. I could not help but reflect, as we struggle to combat a new pandemic, how medical knowledge is constantly evolving.

So, what started as an annoying interruption to my transcription task turned into a fascinating exploration of early Australian medical history and of how one manuscript collection can inform and illuminate another. And I learned that dietary fibre and safe sex did not figure prominently in colonial society…