As an avid reader, and editor of Story Time: Australian Children's Literature's companion publication Story Time Stars: Favourite Characters from Australian Picture Books, I approached the task of choosing my favourite pieces from the exhibition with no little trepidation. How do you prioritise the stories that have imprinted themselves on your soul, shaping your world view into adulthood? Exhibitions such as this one are so successful because of the way we connect in a deeply emotional way with the books we read as children.

There were two that stood out to me as I remembered those stories I’ve read over and over until the scenes and emotions feel like they could be my own memories: Ethel Turner’s Seven Little Australians and Isobelle Carmody’s Obernewtyn.

It has been at least two decades since I last read Seven Little Australians, but the quintessentially Australian scenes are still stuck in my brain, even as many are visions of an Australia long before my time. Some things never change: Turner’s rendering of the bush always made me feel like I could be right there in the middle of the Woolcot children’s lives, though perhaps as a witness rather than co-conspirator—they were much more mischievous than I could ever imagine being. In the end, knowing all too well the effect of a toppling gum tree, I felt it in the very pit of my stomach when Judy saved the General from a falling tree and was then crushed herself.

Ethel Turner, Seven Little Australians. (Melbourne: Penguin Books, 2014), nla.cat-vn6454037.

Despite the heartbreak it delivers to the Woolcot clan, there is something undeniably encouraging about a setting that could be right outside your back door. Seeing representations of our own lived reality gives value to our experiences, even in what may seem like a background element. And that is why it is Turner’s setting that sticks in my brain after all these years, when the minutiae of the Woolcots’ adventures has long faded in my memory.

While I read Seven Little Australians in primary school, the Obernewtyn series was a mainstay of my teen (and twenties…) reading. I read the first book, Obernewtyn, in 2000; the eighth and final book in the series, The Red Queen, was released in 2015. I can’t even remember if it’s the first dystopian novel I read—Robert C. O’Brien’s Z for Zachariah springs to mind—and it certainly wasn’t the last, with Suzanne Collins’ The Hunger Games trilogy a firm staple of my re-read pile. But it is certainly the one that has stuck with me, etched into my literary consciousness.

In my early teens, I identified painfully with the series’ protagonist, Elspeth, who is literally labelled ‘Misfit’ in the early chapters of Obernewtyn. Elspeth is uncomfortable in her own skin and unsure who to trust. Yet she is also special—a common aspiration in awkward teenagers, I’m sure! Telepathy enables her to communicate with animals as well as people, while a curious mind and brave heart empower her to take charge of her fate instead of letting it come for her. Set mainly in a massive, grim stone manor house against the backdrop of an immense mountain range—in a dangerous land poisoned by a nuclear holocaust and governed by a tyrannical council—Obernewtyn feels darkly Romantic, verging on Gothic. And so it creates in me the heightened emotional response of the Gothic: I am Elspeth; her friends are my friends; her fears, my fears; her quest, mine.

Stephanie Owen Reeder, Story Time Stars: Favourite Characters from Australian Picture Books. (Canberra: NLA Publishing, 2019), nla.cat-vn8032620.

Working with author Stephanie Owen Reeder on Story Time Stars was a wonderful trip down memory lane, even before the Story Time exhibition opened. Faced with her own choice between much-loved characters, Stephanie looked not just at the most significant or recognised children’s books from the last century, but also their recognition with awards, translation into other languages and a range of other qualities.

It was fascinating to see in this book just how far our Australian stories have travelled—May Gibbs’ beloved gumnut babies, for example, have been published not only in other English-speaking countries, but in Israel and Japan as well. While it was, of course, delightful to encounter some of my much-loved childhood friends, Story Time Stars also highlighted many wonderful stories that I was unfamiliar with. I knew of former ballet dancer Li Cunxin’s extraordinary biography, Mao’s Last Dancer, but not that he had written a simple but powerful and hauntingly beautiful picture book about his journey (The Peasant Prince, illustrated by Anne Spudvilas).

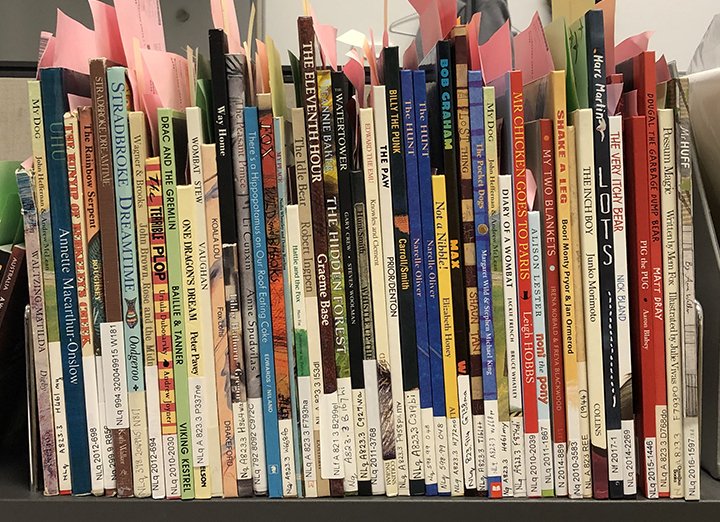

A shelf full of children's books - source material for Story Time Stars.

As Stephanie and I worked together on this book, I had a desk shelf filled with picture books. Poring over them all—the familiar and the unfamiliar—has been one of the highlights of my year. And so I end as I began, with the conviction that the books we read when we’re young—and, I will add, books that are targeted at the young—affect us on a level that rarely happens in adulthood. Revisiting them is a richly emotional experience.

Story Time: Australian Children’s Literature is produced in association with the National Centre for Australian Children’s Literature.