During the development of Cook and the Pacific, the National Library of Australia consulted First Nations peoples from the places Cook visited. Some members of these communities have provided us with responses to and information on objects in the exhibition. You can read these below.

Totaiete Mä (Society Islands)

John Webber (1752–1793)

A Portrait of Poedua c. 1782

oil on canvas; 144.7 x 93.5 cm

National Library of Australia and National Gallery of Australia, Rex Nan Kivell Collection (Pictures), nla.cat-vn321629

‘She is wrapped with päreu (cloth) made of white tapa going down to the knees, which women of all ranks used to make. White tapa is made with ‘uru (breadfruit) bark. The refinement and white colour of the tapa, the tähiri (fan) made of wood, the nape (string of coconut husk fibres) and frizzy hair, as well as her posture show us that she belongs to the chief family. Her released brown undulating hair down on her shoulders and fair skin are also signs of her aristocratic status as lower caste women had shorter hair. Nudity above the navel is often a pride for young ladies, but they could also tie the päreu on one shoulder.’

Natea Montillier Tetuanui, Tahiti, Cultural office of French Polynesia

Ta (Tahitian Tattooing Implement) and Tahitian Tattooing Mallet 1700s

wood, plant fibre, bone

Collection of the Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa, Wellington, FE003010 and FE003009

Gift of the Imperial Institute, 1955

‘Tattoos in Polynesia covered the body (face, neck, chest, armpits, arms, hands, legs, feet, anus) and even the late chief’s skull, most often from the hips to the knees, making the person look as if he wore clothes, with patterns which would trace the memory of events (death, birth of a child, the social position, the passage of puberty), natural elements (flora, fauna), geometrical symbols representing a clan, a god, a totem animal which have similarities with the Pascuan rogorogo ideograms. They would vary according to the origins of the individual. Tattoos were meant to exalt sexual attraction, inspire terror to the enemies. They matched with the splendid ornaments worn for celebrations. They were restricted for young women on the body parts under the clothes, on the waist, the lips, the chin (as an exception, only women used to be tattooed in Fiji). The bloodshed is a proof of courage, a sacred ritual, linked to the metaphysical. People believed they would bring the person a magic power against diseases, recover wounds, help procreate and give birth. The tattooing is close to another rite, the scarification which was performed on the skull, on the tongue, for a relative’s or a chief’s funerals.’

Natea Montillier Tetuanui, Tahiti, Cultural office of French Polynesia

Unknown artist,

after Sydney Parkinson (c. 1745–1771)

and after John James Barralet (c. 1747–1815)

A View in the Island of Otaheite with the House Called Taupapow, under Which the Dead are Deposited 1773

pen and ink; 25.0 x 33.1 cm

Kerry Stokes Collection, Perth, 2012.070.07

‘A fare tüpapa’u (house for embalming) was built for chiefs. The tahu’a miri (embalmer) would tämiri (extract) organs from the guts and skull, fill them with scented plants like the miri (basilic and fragrant resins) there, anoint the skin with perfumed oil, let the corpse dry out of its flesh, mucus and blood on the tu’ura’a-turuma or taha-tüpäpa’u … which was placed on a platform higher than that of a house, near or on the marae, at more than ten feet from a house because of the smell. Then he would ha’apa’a (mummify) the body by wrapping it in perfumed tapa and a mat, often in a sitting position. The roof was meant to prevent rain from ruining the embalming process.’

Natea Montillier Tetuanui, Tahiti, Cultural office of French Polynesia

Chief Mourner’s Costume (partial) from the Society Islands 1700s

shell, plant fibre; 91.0 x 56.0 cm

Collection of the Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa, Wellington, FE000336/1-5

Gift of Lord St Oswald, 1912

‘The tahu’a heva (mourner priest) wore a pü-tahi (costume) during the heva (mourning ceremony) or pütopo-pau reserved for ari’i (chiefs). People fled when the priest approached the village … as he makes his tete (mother of pearl castanettes) clink and as his warriors catch one or more victims designated by him for the human sacrifice to be held on the marae (sacred place).’

Natea Montillier Tetuanui, Tahiti, Cultural office of French Polynesia

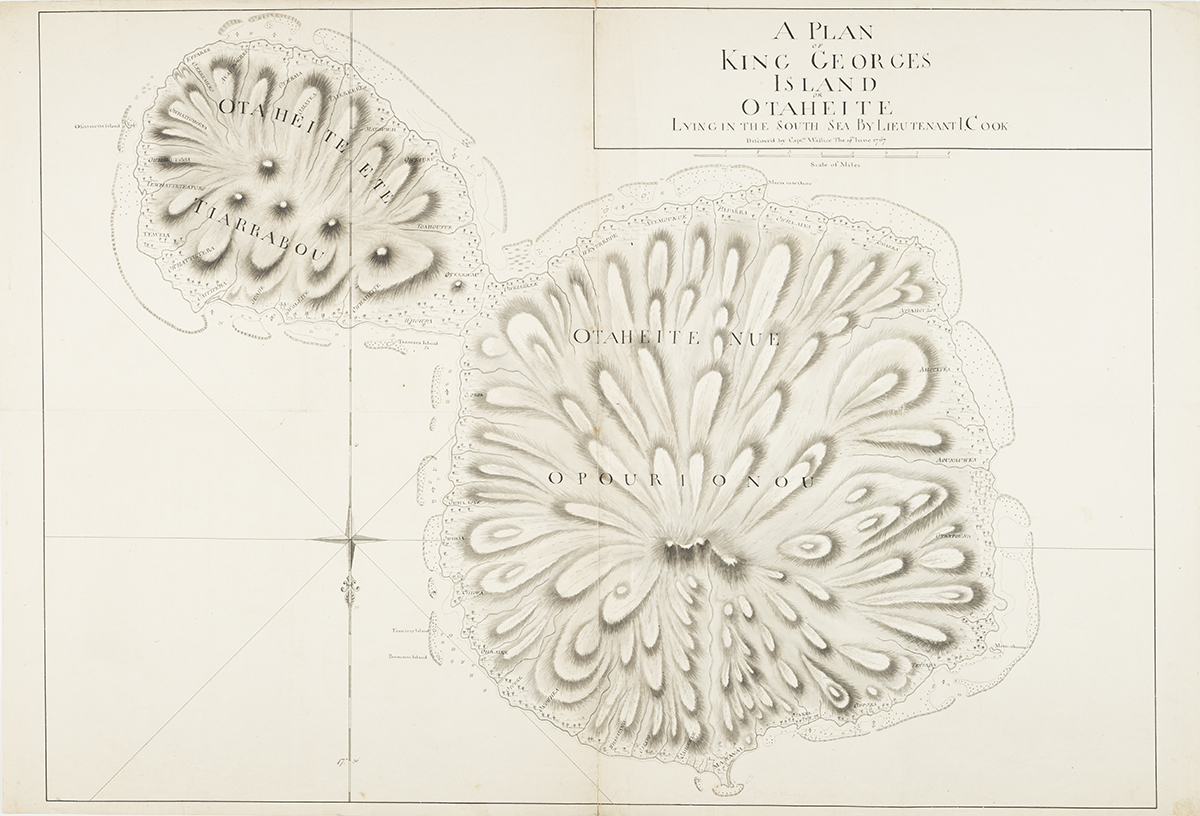

James Cook (1728–1779) and Isaac Smith (1752–1831)

A Plan of King Georges Island or Otaheite Lying in the South Sea1769

ink and wash; 63.3 x 88.3 cm

State Library of New South Wales, Sydney, SAFE/DLSPENCER168

‘Cook is very renowned amongst Polynesians to have been an excellent navigator and good observer. This map shows the several valleys, villages and rivers of Tahiti.’

Natea Montillier Tetuanui, Tahiti, Cultural office of French Polynesia

New Holland (Australia): Cooktown

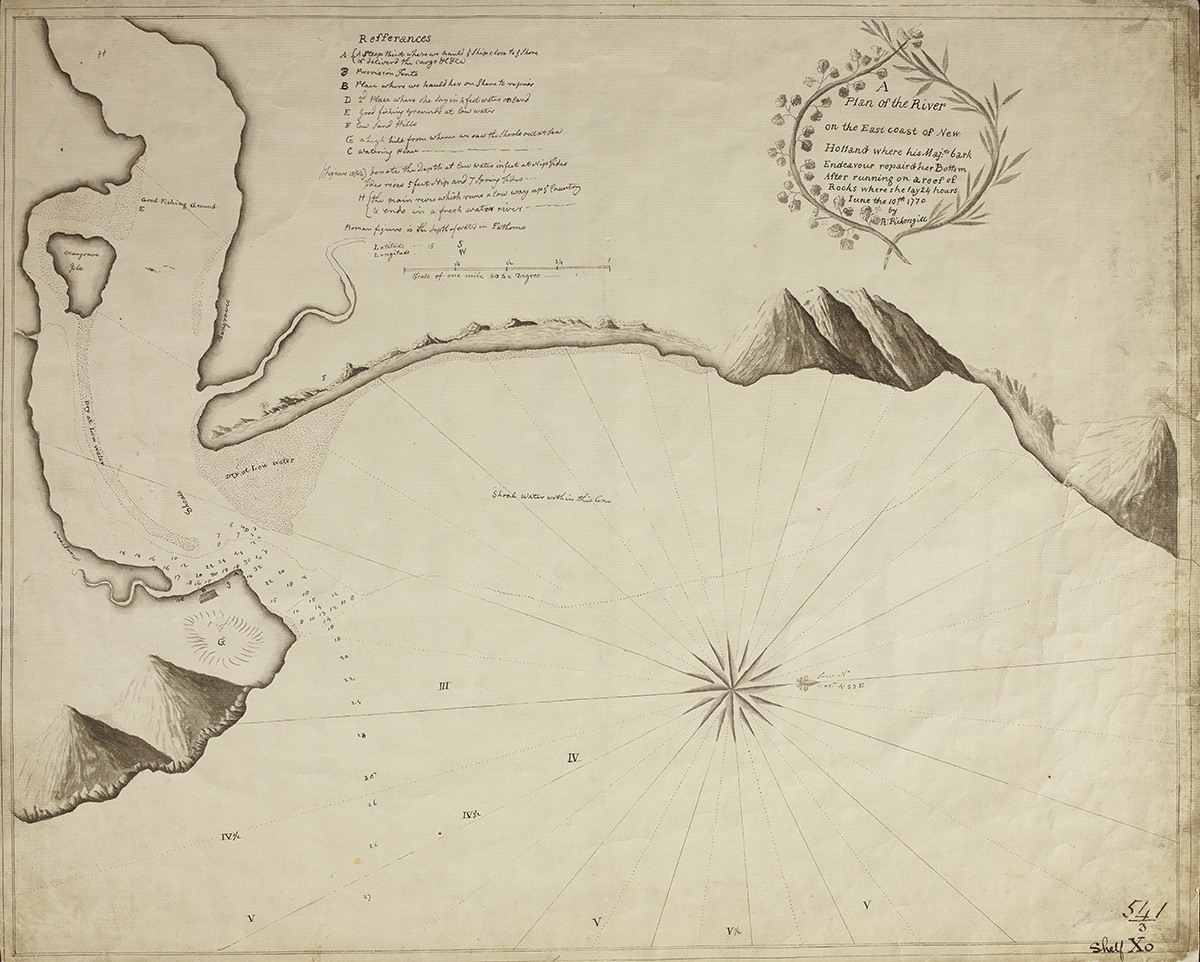

Richard Pickersgill (1749–1779)

A Plan of the River on the East coast of New Holland Where HM Bark Endeavour Repaired Her Bottom After Running on a Reef of Rocks Where She Lay 24 hours 1770

The National Archives, UK, ADM 352/381

© Crown Copyright – image courtesy of The National Archives

‘We have a special story to tell, because when Captain Cook came here in 1770 to repair his ship, he didn’t realise he had landed on a neutral zone. This Clan Land of Waymburr was a place where women from surrounding Clans came to give birth, marriage alliances were made here, conflicts were settled here. Bama came here for initiation ceremonies, for celebrations. The law said that there was no blood to be spilt on this bubu on this land. Not many people know that without the cultural and spiritual laws of the Guugu Yimithirr Bama, Cook would not have had a successful first voyage.’

Alberta Hornsby, Guugu Yimithirr Traditional Owner and Bama Historian, Endeavour River

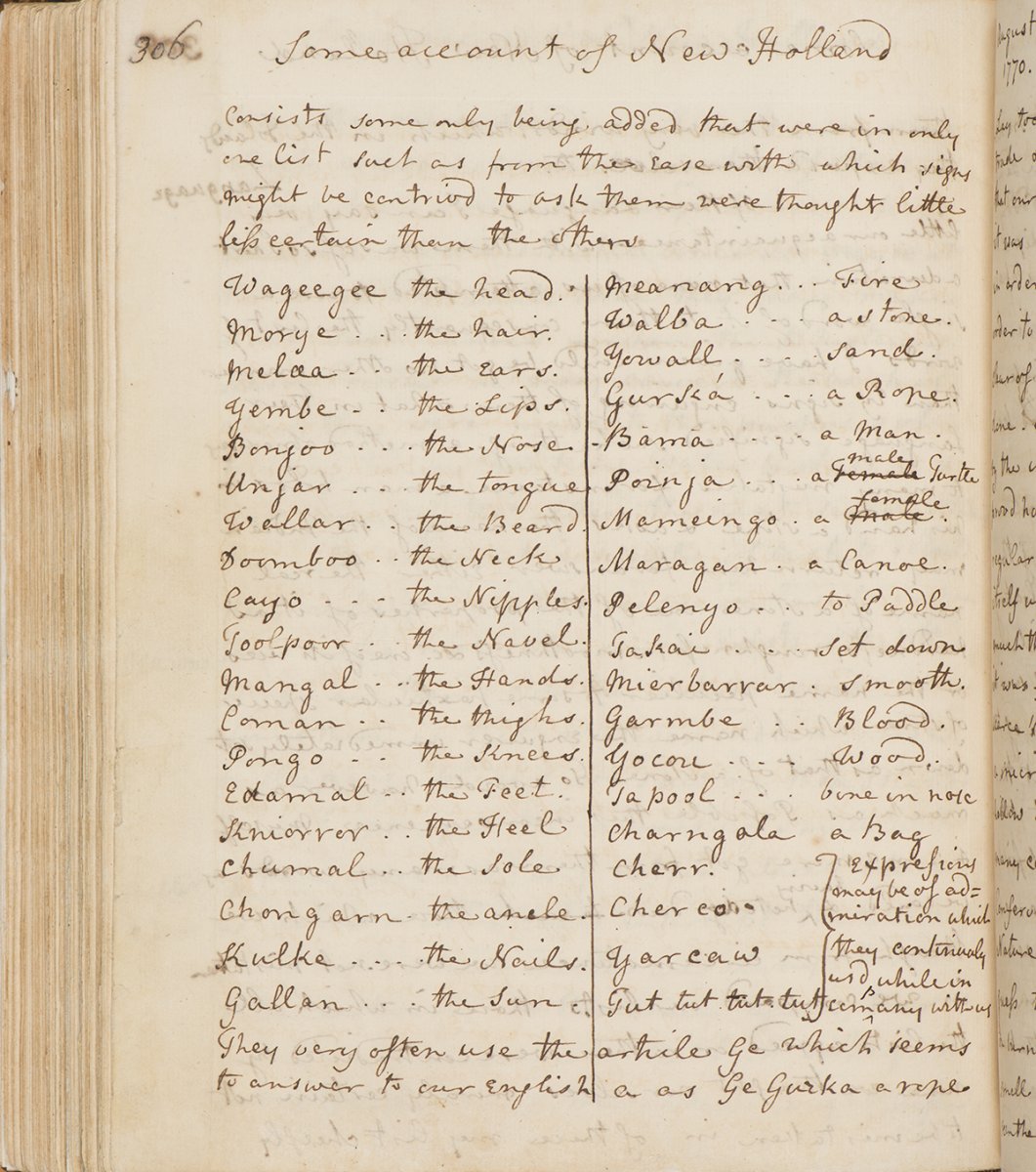

A Short Vocabulary of the Guugu Yimithirr People, Waalambaal Birri (Endeavour River)

in Joseph Banks (1743–1820)

Endeavour Journal 15 August 1769–12 July 1771

State Library of New South Wales, Sydney, SAFE/Banks papers/ Series 03.02

‘It’s really interesting to look at this wordlist from 1770, because even today, a lot of the words are still recognisable, but it also contains a lot of words that I don’t recognise, but may have been language that has been used in the past, and we don’t use it today.’

Alberta Hornsby, Guugu Yimithirr Traditional Owner and Bama Historian, Endeavour River

New Holland (Australia): Ulladulla

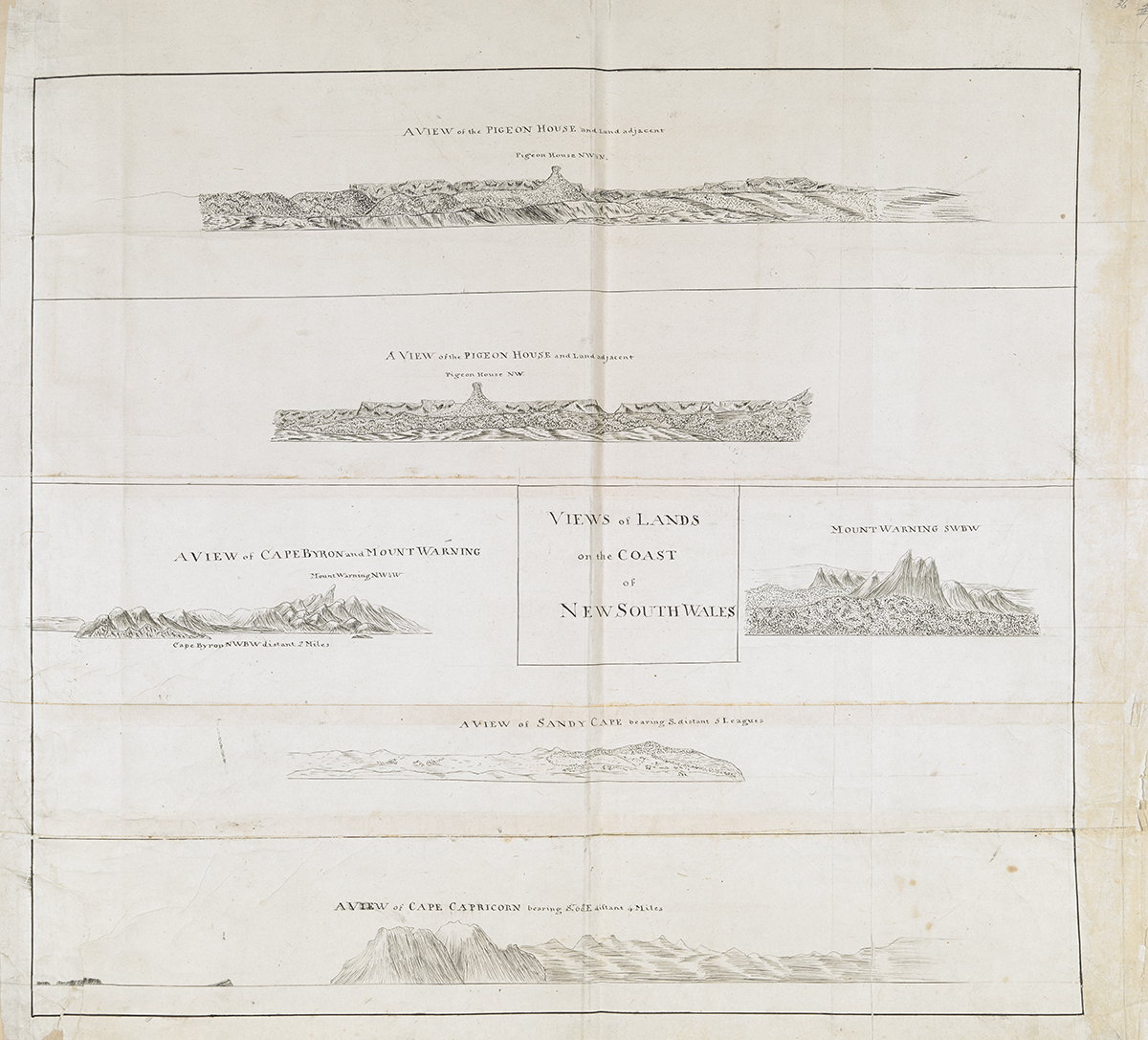

Charles Praval (copyist, d. 1821),

after a voyage artist

Views of Lands on the Coast of New South Wales 1770–71

ink; 54.0 x 62.0 cm

British Library, London, Add MS 7085, f.36 b, c, e

© British Library Board

‘My people have lived in this area for millennia. Pigeon House or Didthul as we call it, is a very sacred place to us. It has men’s sites and women’s sites, it has art sites. It is not a site that we visit constantly but it is a place that we hold very dear to our heart. It was also very well known outside our area and is also a very sacred place for other Aboriginal people who live both north, south and west of us.’

Shane Carriage, Murramarang, Ulladulla, NSW

‘A lot of the knowledge that we hold is not knowledge that’s found in books. A lot of the knowledge that we’ve got comes down from our Aboriginal ancestors all passed on through generations and generations. We talk about our local sites Didthul (Pigeon House). Places like that are part of our songlines, they connect the mountains to the sea.’

Victor Channell, Murramarang, Ulladulla, NSW

Pacific Encounters: Tonga

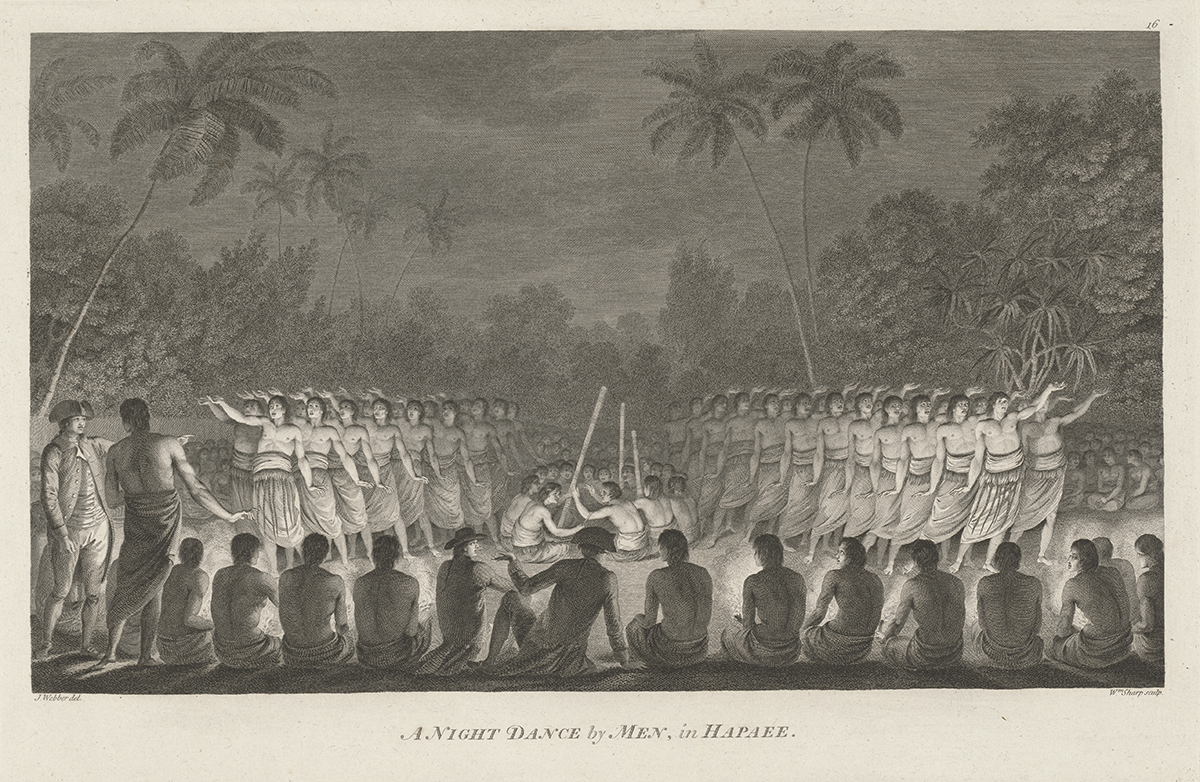

William Sharp (engraver, 1749–1824),

after John Webber (artist, 1752–1793)

A Night Dance by Men in Hapaee 1784

engraving; 27.0 x 41.8 cm

National Library of Australia, Rex Nan Kivell Collection (Pictures), nla.cat-vn2098424

‘As you can see here, Captain Cook and his crew from the Resolution and the Discovery were treated to lavish feasting and magnificent entertainment. The warmth of the people really came out. Their talitali kakai (hospitality) and anga’ofa (generosity) were quite obvious to Captain Cook. Hence he gave the name the Friendly Islands or ‘Otu Motu Anga ‘Ofa.’

Manutu’ufanga Naufahu, Tongan Community, Canberra

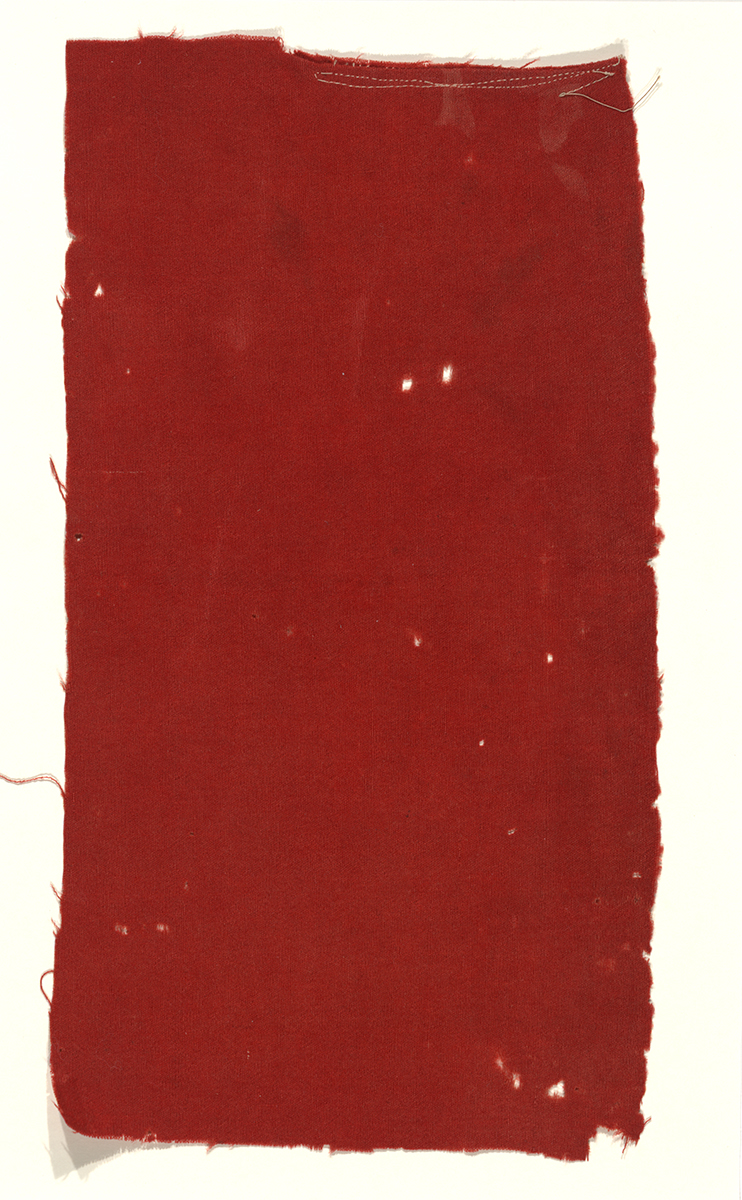

Piece of Cloth Given by Captain Cook to ‘The Tamaha’ of Tonga 1777

linen; 31.7 x 15.6 cm

National Library of Australia, Pictures Collection, nla.cat-vn596662

‘In one of Captain Cook’s voyages or visits to Tonga he gave red cloth to the Tamaha, and that is the daughter of the king’s sister and she’s the highest in the land. It is interesting to see that the colour is red, because most of the things back home valued by people are red and most of the coconut husks which they made some of their cloth from is in that colour too. So a sisi fale, which has been woven from coconut husks, is normally worn by the Tu‘i Tonga Fefine (the king’s sister) or the Tamaha. And it may be the connection why the red linen cloth was given to the Tamahaby Captain Cook, as a gift.’

Stella Pahulu Naimet, Tongan Community, Canberra

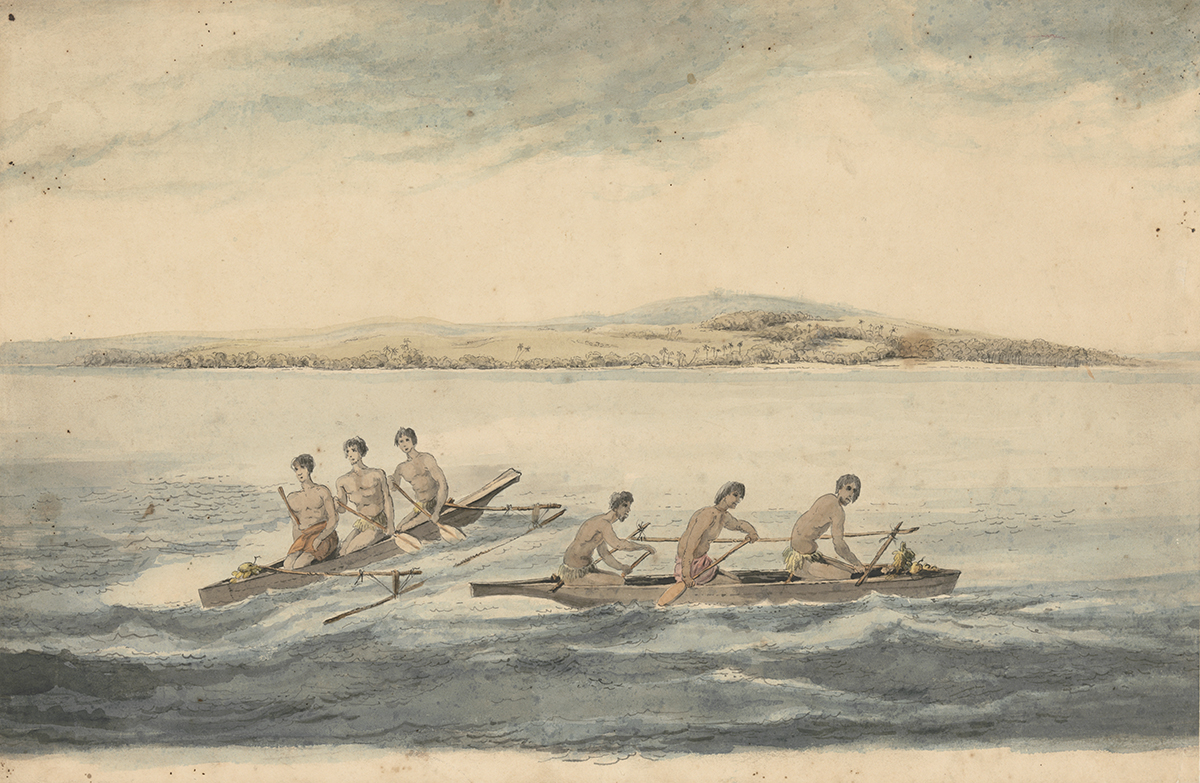

Attributed to John Webber (1752–1793)

Canoes of the Friendly Islands 1777

watercolour; 27.1 x 40.8 cm

National Library of Australia, Pictures Collection, nla.cat-vn2649034

‘This picture tells us that Tongans are sea warriors because they loved boats and they lived by the sea and this is their connection to the other islands–having to use canoes. But nowadays they use this as their favourite sport. It’s called tawa alo. But in Cook’s days, it used to entertain kings and royal families.’

Sioana Faupula, Tongan Community, Canberra

Nootka Sound

John Webber (1752–1793)

Indians of Nootka Sound April 1778

sepia wash; 19.5 x 14.5 cm

National Library of Australia, Petherick Collection (Pictures), nla.cat-vn2644000

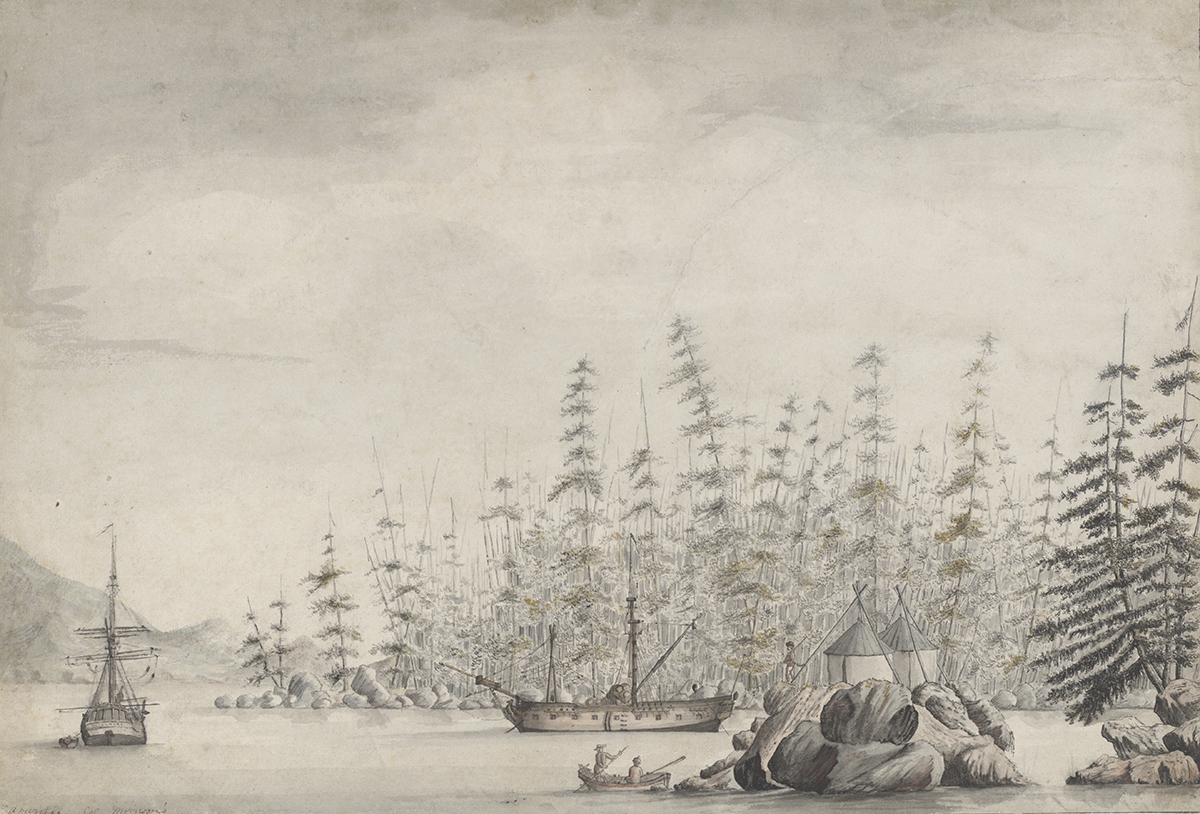

William Wade Ellis (1751–1785)

A View in Ship Cove 1778

pen and watercolour; 35.7 x 52.5 cm

National Library of Australia, Pictures Collection, nla.cat-vn2058465

‘The historical drawings by Webber and artists like Ellis are the greatest visual legacy of the Cook era. These eighteenth-century images provide us with a snapshot of our past as it was in real time without today’s technology. These pictorial records document important moments in world history–in our history. Understanding the significance of the events and persons at the time had a different meaning than today. As Nootkan people, we have questioned the context of the drawings and what has been depicted and commemorated has evolved to difficult and challenging times for us. Today, we are rethinking our histories and our futures. We continue to appreciate the artists' skill and creativity and how this exhibition provides a window of opportunity to honour our past and for the viewer to better understand its impact on human history and the relevance to the current and rising global interest with Indigenous issues.’

Margarita James, President, The Land of Maquinna Cultural Society

Michel Tuffery (b. 1966)

Cookie from Aotearoa to Mangaia 1777 2011

acrylic on canvas; 40.0 x 40.0 cm

Courtesy of the artist and Andrew Baker Art Dealer, Brisbane

'After an unfriendly welcome from the people of Mangaia on 29 March 1777, Cookie quickly set sail north landing in Atiu; he missed the main island of Rarotonga. The hibiscus are a metaphor for his arrival to what is now known as the Cook Islands, which I’ve always personally questioned–how did we inherit the name ‘Cook?’'

Michel Tuffery, artist

Michel Tuffery (b.1966)

Cookie in Te Wai Pounamu Meets Cook Strait 2011

acrylic on canvas; 40.0 x 40.0 cm

Courtesy of the artist and Andrew Baker Art Dealer, Brisbane

'[This painting] Depicts Cookie when he realised Te Wai Pounamu (South Island) and Te Ika a Maui (North Island) weren’t connected, whence is the reason why it’s named the 'Cook Strait'. The Ika in his ears are a metaphor to Tupaia, an Arioi from Raiatea, there is no existing image of Tupaia. He was Cookie’s constant guide and translator on his first voyage.'

Michel Tuffery, artist