This set of instruments includes a sundial for telling the time, a spirit level, a compass and an astrolabe. It was used by Cook as early as the 1750s. It is compact and provides a handy reference for a man at sea.

Cook’s Box of Instruments c. 1750

wood, engraved brass, glass, letterpress

National Library of Australia, Rex Nan Kivell Collection (Pictures) nla.cat-vn2640976

When the British reached the Pacific, they found knowledge systems to rival their own. Pacific navigators observed the stars, ocean currents and wave effects, air and sea interference patterns caused by islands and attols, the flight of birds, the winds and the weather.

European navigation required charts and instruments to address the critical problem of position at sea. Aboard ship, officers and crew with specialist skills, checked and re-checked observations.

Yet, as Cook saw at first hand, navigating the Pacific could be managed using knowledge passed on by oral tradition, without the aid of instruments. And exponents such as Tupaia, the Ra'iatean priest and navigator who joined the Endeavour voyage in 1769, could direct them across the ocean from island to island.

Canoe of Otaheite

Voyage artists depicted a variety of Polynesian Indigenous craft, from small bark canoes to large ocean-going vessels. Adapted to long-distance voyaging, double-hulled canoes with sails and rig could track well while sailing across, or reaching into, the wind, with the navigator ‘reading’ the ocean for sailing directions or bearings to distant islands. This has been described as an outrigger canoe (va’a motu). Four figures are shown, two of whom are paddling. Fruit was carried on the crossbeams.

John Webber (1752—1793)

Canoe of Otaheite 1777

ink and wash

National Library of Australia, Rex Nan Kivell Collection (Pictures), nla.cat-vn2212925

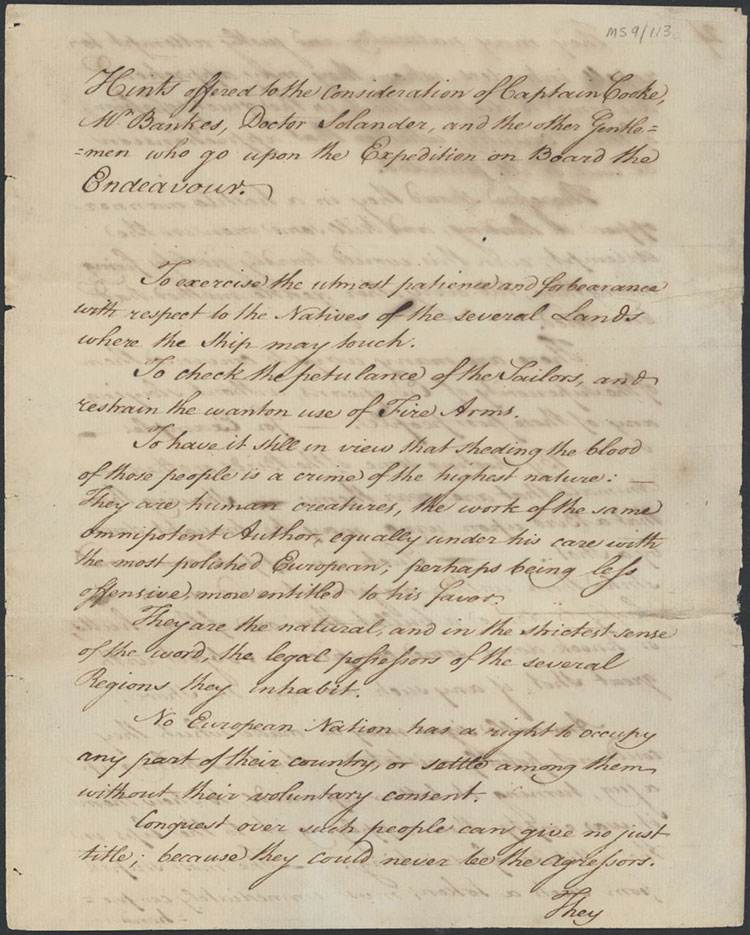

Hints Offered to the Consideration of Captain Cook

Written soon before the Endeavour set sail from Plymouth, this important letter from the President of the Royal Society provided Cook and his companions with the Society’s views on how they should conduct themselves. The Hints counselled them ‘to exercise the utmost patience and forbearance’ in the treatment of any inhabitants of lands visited.

James Douglas, 14th Earl of Morton (1702–1768)

Hints Offered to the Consideration of Captain Cooke, Mr Bankes, Dr Solander and the Other Gentlemen Who Go upon the Expedition on Board the Endeavour 10 August 1768

ink

National Library of Australia, Papers of Sir Joseph Banks (Manuscripts), nla.cat-vn2049605

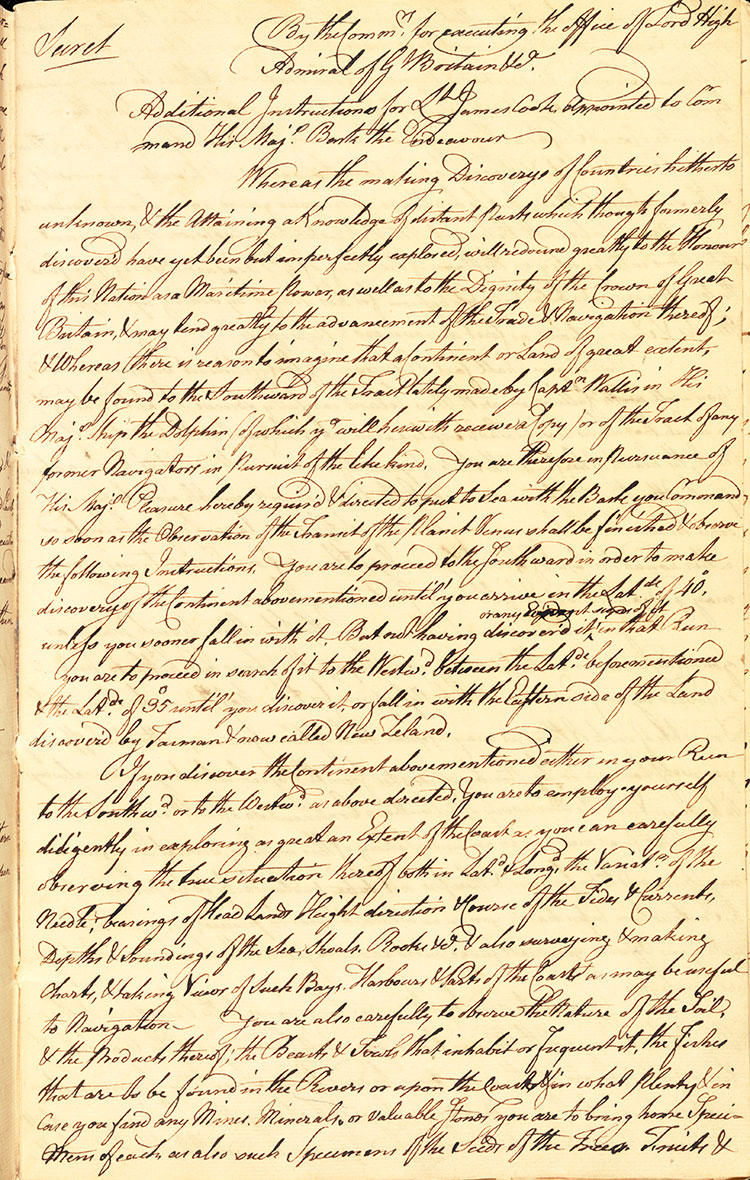

What were the Secret Instructions?

When Captain James Cook left Plymouth in 1768, bound for Tahiti, his official mission was to observe the Transit of Venus.

However, he carried with him secret instructions from the Lords of the Admiralty. When he opened them he found orders for him to search for a southern continent of ‘vast extent’.

The Secret Instructions map out how he should document what he finds, and act, particularly in relation to interacting with local inhabitants and ‘taking possession’ of lands he visits. It tells him to take possession of lands encountered if they are uninhabited, or if inhabited, with the consent of the ‘natives’.

Additional Instructions

Written in the copperplate hand of Cook’s clerk Richard Orton, this ‘letterbook’ records Cook’s correspondence while commanding the Endeavour. It contains a copy of his secret additional instructions for the voyage, which he was instructed to follow after observing the transit of Venus at Tahiti. Cook is told to search for the ‘Great South Land’ and take possession of lands encountered if they are uninhabited, or if inhabited, with the consent of the ‘natives’.

Additional Instructions for Lt James Cook Appointed to Command His Majts Bark the Endeavour (Secret) 30 July 1768 in Cook’s Voyage 1768-1771: Copies of Correspondence

ink

National Library of Australia, Manuscripts Collection, nla.cat-vn1120886