Dr Andrew Levidis explores the transnational network of bureaucrats, soldiers and propagandists, who served the Japanese and Manchukuo empires and their role in shaping right-wing and socialist politics in Cold War East Asia. It rethinks the transitions from empire to Cold War beyond the binaries of superpower conflict and national experience of decolonization.

21 07 01 - The Dreamworlds of Empire Dr Andrew Levidis

*Speakers: Libby Cass (L), Andrew Levidis (A)

*Audience: (Au)

*Location:

*Date: 01/07/2021

L: Welcome to the National Library of Australia. I’m Libby Cass, Director of Curatorial and Collection Research here at the National Library.

I’d like to begin by acknowledging Australia’s first nations peoples as the traditional owners and custodians of this land and give my respect to elders past and present and through them to all Australian Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples.

This afternoon’s presentation is by Dr Andrew Levidis, one of the 2021 National Library of Australia fellows. Andrew’s fellowship is one of two fellowships in Japan Studies awarded this year which are both funded through the H S Williams Trust Fund. Andrew is presently a research associate fellow in the Faculty of Asian and Middle Eastern Studies at the University of Cambridge and a member of the project charting the geography of power visualising the shifting landscape from imperial to post-war East Asia through war crimes trials.

Andrew’s fellowship project, The Dreamworlds of Empire, focuses on Manchukuo’s destruction at the hands of the Soviet Union in August 1945 which haunted the right wing and socialist imagination and had a profound impact on the hostility towards the USSR and international Communism. He explores the transnational network of bureaucrats, soldiers and propagandists who served the Japanese and Manchukuo empires and their role in shaping right wing and socialist politics in cold war East Asia.

Andrew has drawn on the Library’s unique collection that documents Japanese political history in the 20th century including a collection of documents, notebooks and pamphlets of the Japanese Socialist Party. Please welcome Dr Andrew Levidis to discuss his project further.

A: Thanks so much, Libby, for that very kind introduction. I hope the work comes out well for it.

I want to thank first of all the Harold S Williams Trust for providing the means for the fellowship and long may it remain because it is an essential pillar for the study of modern Japanese history in Australasia and in the world and its importance will only grow in time.

I’d like to express my thanks to the fellowship section here at the Library, to Sharon and Simone without whom I might never have found my way back from the UK to Australia. Their warmth and their good humour have made all the difference.

One of the things I realised when I came back to Australia was the introduction, the traditional owners of the land so if you’ll excuse me as a returned Australian, I might give my own little version of that. I think for me to respect the owners of the land past and present we have to enshrine the Uluru Statement of the Heart into law and to me that I think is important.

So, during my stay here at the National Library I began preliminary work on a second book project which explores the transwar discourse and imaginary of the Japanese right from the world of empire to the cold war and their role in shaping anticommunism internationalism in 20th century East Asia. At the heart of these transwar projects are the artefacts of empire, of the wartime empire and cold war internationalism. Pamphlets, speeches, journals, conference proceedings, personal papers and diaries of renowned and forgotten idealogues of the right in post-imperial Asia. The reconstruction of anti-Communist internationalism in East Asia requires a multi-archival and multilingual approach involving Japanese sources in Japanese, Korean and Chinese and it’s here that I want to say a few words about the collection at the National Library.

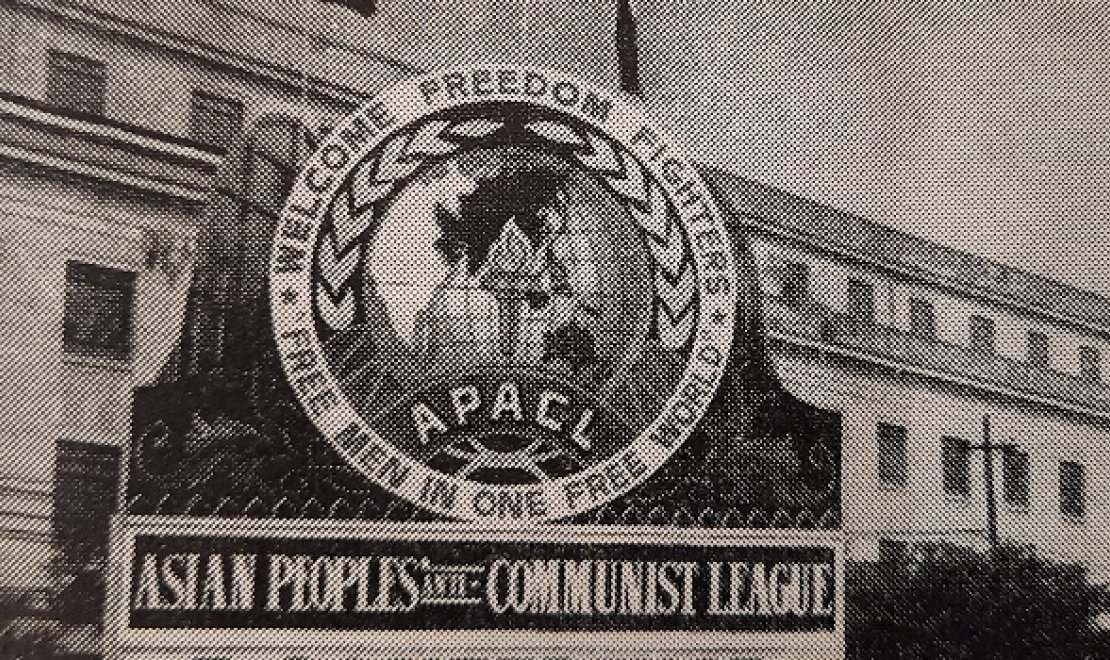

The National Library of Australia houses as I found through my stay here a sizeable repository of archival material on cold war Asia which has not necessarily made its way into contemporary major works on this era. I’ve spent the last three months working through the Library’s archives and in the process coming across pamphlets, informal publications, documents, magazines associated with the two major transnational anti-Communist networks, the Asian People’s Anti-Communist League and the Asian Parliamentarians’ Union.

Although the volumes overlap in some regards to holdings in Japan, Taiwan and the United States the breadth of the material available here at the National Library, many of which were delivered by the organisations themselves, provides tantalising details of the idealogues and the ideologies and the inner workings of internationalism of the right in cold war Asia.

So the NLA collection lists well in excess of 60 major documents relating to both the Asian People’s Anti-Communist League and the Asian Parliamentarians’ Union in a mix of Japanese, Chinese, English and other sources with the bulk of the sources focusing on the periods between 1955 and the mid-1980s. The NLA possesses a near complete collection of the Asian People’s Anti-Communist League’s pamphlets and their ideological tracts which provide I think a real insight into the group’s mechanics and how they disseminated their anti-Communist world view across Asia. The titles of the books range from the studies of people’s communes to whither Indonesia, PKI and the CCP.

The Library has a near complete holding of the newsletter, Frontlines, published in French and English out of a makeshift Saigon office out of the then Republic of South Vietnam. The Library’s collection also, and I think uniquely for not just East Asian specialists or historians of the cold war but for historians of Australia, the NLA’s collection provides a unique glimpse into a time and place from the 1950s through to the 1970s when Australian politicians and political and religious conservatives, people like Euston R Tracey, Kevin Cann or Senator George Hannan turned to Asia as they sought to continue their ideological fight against both the Labor Party, the unions and the left in Australia.

Now let me shift gears a little bit. The project as I mentioned I’ve been working on here broadly conceived is a continuation of my work at the intersection of empire, global intellectual history and modern Japanese and East Asian history but it’s also a new departure. The project repositions the formation of Japanese and East Asian anti-Communist internationalism as an integral episode in the global cold war, challenging dominant historical narratives which focus mostly on the United States and western Europe.

Although Asian anti-Communist regionalism peaked in around the late 1970s you could argue, the institutions themselves never disappeared. Rather they were rebranded, they rebranded themselves under new names and with new missions as auxiliaries in the conservative right in the 1980s forming what might be seen as a powerful thread of continuity into the late 20th century and up to the present.

As a transwar political tradition anticommunism has its own history, one of striking continuities but also contradictions, reformulations and repurposing. It was never an unchanging principle. Rather it was a malleable web of ideas and politics which changed in response to the concrete political circumstances and across different eras. In Japan in the 1920s anticommunism was tied to military fears of the stability of the empire rather than ideological hostility to the Soviet Union. By the mid-1930s anticommunism was part of the anti-Comintern Pact with Germany and with national socialist Germany and Mussolini’s Italy and later the new order reformists’ drive to overthrow the existing domestic and international status quo.

In the transition to the cold war anticommunism provided what one historian has called an enabling idea which underpinned a conservative effort to both reconcile with the United States but also to fight a rear-guard action against the reforms of the occupation at home in Japan.

In the transition from the world of empire to the cold war anticommunism was reinvented and invested with a new ideological repertoire. In publications such as The Nation in Politics Minzocotesage intellectuals, propagandists and writers’ brokers made explicit the connections between the red purges in Japan and the militarised projects to counter the spread of communism overseas in Korea and Taiwan and southeast Asia. In articles and roundtables politicians and thinkers fashioned new forms of postimperial Asian solidarity as they navigated, survived, upheld and contest empire. The same men and women who during the 1930s and ‘40s had sustained Japan’s wartime new order in the post-war now became anti-Communist, recasting their pre-war commitments into a punitive third way of international politics.

It was Japan’s mission, they argued, to mediate and reconcile Asian anticolonialism with the anti-Communist west. In their retelling and misremembering Japan emerges as a true anticolonial power, one whose fight against western imperialism and with now a fight for national liberation against the red imperialism of Moscow and Beijing.

In what follows I argue against the severing of empire and the cold war and collapsing of the boundaries between imperial, transnational and area studies. To do so I will examine how the Japanese right drew on Manchukuo empire, the fallen state of Manchukuo and its ideology while adjusting them to the dynamics of the cold war in East Asia.

In post-1945 Japan the memory of Manchukuo, the fallen empire in northeast China, was expressed through distinctive mode of political aspiration, personal desire and nostalgia. Morishika Hesire’s 1959 Manchurian Ballad released 14 years after the destruction of Manchukuo and performed in a haunting mix of Japanese, Mongolian and Russian evoked howling winds, daily struggles and ordeals of the unforgiving cold and bleak Manchurian winter.

In postimperial memoirs, and that is surely what they are, what the memoirs of imperial service and the agonies of decline are, Japanese officials conveyed the materiality and the transactions of the severed colonial ties, the industrial behemoths of Anchon, the agricultural plentitude dreams of an economy of self-sufficiency. For these men Manchukuo was a lost object of identification entwined in a kind of imperial imaginary of Japanese modern power and war pancreatics, a riven domain of railways, inter-imperial competition and imperial anxieties.

What is missing in this imperial nostalgia of course was any recognition of the violent colonialism-initiated industrialisation, militarised workplaces, concentrated resettlements, populations interned, dispossessed, experimented on. It’s never mentioned.

How Manchukuo captured the transwar Japanese right wing’s imagination owes much to the circumstances of the 1930s and 1940s for on a remote periphery of the Japanese empire in September 1931 radical military officers of the Kwantung Army, horrified by the disruption of global depression, intensified military threat from the Soviet Union and committed ideologically at home to a Showa restoration launched a series of military campaigns to overthrow the northeast and Chinese warlord, Zhang Zuolin. In the hands of prominent Japanese Imperial Army commanders, Ishiwara Kanji, Negaki Sayshero and Sasaki Tōichi, the Manchurian incident was transformed into a highly militarised 14-year state-building enterprise wedding together military necessity with anticapitalism, agrarianism and empire.

The ideological repercussions of this drove the politics of the metropole in the early 1930s collapsing the political cabinets in Tokyo and reconstitute the discourse, priorities and orientation of Japanese empire.

The destruction of the state of Manchukuo at the hands of the great powers in August 1945 following the Soviet invasion haunted the right wing imagination and it exerted a profound impact on their ideological hostilities towards the USSR and international communism. As accounts of the brutal violence of Manchukuo’s imperial collapse filtered back from the wholesale rebellion of the army to the capture of the Manchukuo emperor, the future Premier, Kishi Nobusuke, then imprisoned in Sagamo among the traitors, warlords, leaders of the puppet regimes and exiled armies from the edges of the empire followed the course of the Chinese civil war intently.

Shenyang’s falling, Manchuria’s completely in the hands of the Communist Chinese as is most of the northern part of Shandong, Communist forces are heading towards the banks of the Yangtze, he wrote. In his prison diaries for November in 1948 Kishi evoked again the violent ends of Manchukuo as he set out his proposal for the raising of a multinational volunteer division of Japanese military veterans and right-wing youth defying the cause of anticommunism in Asia.

The invocation of the fallen Manchukuo empire was no aberration. Nor were they the solitary ruminations of a former high official of the deposed Emperor Puyi. During the 1950s and the 1960s officials of the fallen Manchurian Empire, the frontline soldiers of Japan’s greater East Asia war sought to halt what they saw as the post-war decadence of Japan and the march of communism in East Asia. These former soldiers, bureaucrats, propagandists and ideologues sought to reframe themselves as soldiers in a larger global and regional ideological war.

The Japanese of the right were no strangers to internationalism as many historians have shown. Rather, empire served as a touchstone for their political imaginary and it played a very large role in structuring their fears to anticommunism. Through their peregrinations to the frontlines of the wartime empire in Manchurian China, Japanese writers’ lives and their careers were enmeshed in the construction of the wartime new order at the height of what David Motadel has called the global authoritarian moment in the 1930s. With the cannonade of the Manchurian incident and renditions of the song, Asia, Asia, Our Asia ringing in their ears, many of whom were imperial bureaucrats, many of whom went on to political leadership in the post-war, styled themselves as the vanguard of a world revolutionalised by strong leadership, militarism, physical discipline and collectivism.

As we shall see pan Asianism which united nationalism and internationalism with notions of cultural unity, racial kinship and geographic proximity were key to their transwar world views. As we unpick the tangled schemes of these cold war anti-Communist networks we are led in unexpected directions. Some threads connected back to the remarkable presence of many former officials of the Manchukuo empire in post-1945 Asian internationalism. Other strands connect to the careers of former Korean and Chinese soldiers of the Imperial Japanese Army and still more to the collaborationist regimes and the armies from Indonesia, The Philippines and Vietnam where anticolonial nationalists flocked to Manchukuo to seek their fortunes.

At the height of the Sino-Japanese war an elite group of students from across Asia were selected to study in Manchuria to train what they imagined to be the post-war elite of a Japanese-dominated regional order. At the end of the war these students streamed back to their home countries and they made their lives from Niigata in Japan to Dalian and from Tokyo to Lambator and different places.

What did they see in the Chinese northeast? What survived of the dreams which drove them to Manchukuo at the height of the Japanese Empire and how can we understand the enduring intellectual and personal connections that crossed the disappearance of Manchukuo, the collapse of the Japanese Empire, the cold war and up to the present? What I want to suggest is we need to widen our angle of approach when considering the imperial afterlives of the Japanese Empire and of Manchukuo in particular as inspiration, moral lesson, offer some an alternative to the global ideological tensions of cold war binaries.

To a remarkable degree the memory of the Manchukuo Empire formed I think a subterranean or a key, if contested one, of the Japanese right wing cold war imaginary, one which the Japanese turn to seek alternatives to the binaries of the cold war and one which they transformed into a touchstone for defining Japan’s informal connections with Asia, with Asia’s anticolonial nationalist leaders from the 1950s well into the 1970s.

So despite Japan’s remarkable transition into a key ally and stronghold of American power in Asia ex-imperial elites remained uncomfortable with their subordinate place in the US sphere of influence and so they recast their wartime Pan-Asianism into a cultural vision of Japan as a bridge between the US and cold war Asia. Anti-Communism provided the vehicle to institutionalise and sell their ideas by marketing wartime connections with it and political expertise to help America navigate a rapidly decolonising world.

The Chinese civil war served as the initial proving ground for Japan’s new anti-Communist international and the geopolitical background to the foraging of the security alliance with the United States. In this area veteran politics became a place of anti-Communist mobilisation. Ex-commanders of Japan’s China Expeditionary Army under General Okamura Suji helped train KMT armies and nationalist Chinese armies on Taiwan in their fight against the Chinese Communists whilst in the Republic of Korea Major General Park Chung-hee launched a military evolution with a cohort of Korean soldiers trained in the Manchuria Military Academy in May 1961.

Within Japan military veterans continued their fight against Communism and other internal enemies working for the occupation’s G2 intelligence at the height of the American-initiated red purge of leftist and progressive forces from public life. Between the 1950s and the 1970s ex-prime ministers, suspected war criminals, returnees from the Manchukuo Empire, shadowy fixers and ex-imperial military commanders played a central role in shaping right wing politics not only in East Asia, recasting imperial Japan’s visions of state power, military-led development and anti-western internationalism into an alternative cold war internationalism.

A diplomatic campaign to transform Japan into a stronghold of anticommunism was enmeshed in a world of political conferences, mass movements, anti-Communist violence and American conservative media circus. At the centre of this transnational anti-Communist movement was a diverse but highly organised transnational anti-Communist network, the Asian People’s Anti-Communist League, the APAPCL, founded jointly by the Republic of Korea and Taiwan, the Asian Parliamentarians’ Union and the international spiritualist movement, the International Federation for Victory over Communism.

What we see when we look at this tangled history is that defeat in war did not preclude international influence for the Japanese. Through their transnational networks Japanese ex-imperial leaders developed close personal and professional relationships with former enemies and leaders of ex-colonies, people such as Chiang Kai Shek who’d fled to Taiwan in 1949 following defeat in the Chinese civil war at the hands of Mao Zedong where he would govern until his death in 1975, and Park Chung-hee, the head of the ruling military junta who seized political power and established a political regime in Korea zealously dedicated to modernisation.

For nearly three decades these anti-Communist networks structured Japan or helped structure Japan’s post-war return to Asia and they formed a core of what can be seen as a countermobilisation to the international solidarity and anti-imperialism put forth at the Afro-Asian Conference in Bandung, Indonesia in 1965. In the hands of these Japanese elites and authoritarian post-colonial leaders in south-east Asian internationalism and transnational networking were harnessed not for national liberation or third world state-making but for a counterrevolutionary purpose.

One of the most important places I think to look for glimpses or gleamings of Manchukuo’s afterlife in the cold war is in response to the Japanese writers to the meaning of the first Afro-Asian Conference in Bandung. Bandung became a proxy in their debates for these fierce divisions among conservatives within Japan and elsewhere over the memory of Manchukuo. As part of their efforts to forget an international of the right ex-imperial leaders recast Manchukuo’s vision of state power and military-led development into an alternative regionalism.

This became a vision for them, a way to seek a third way through the binary – not simply of capitalism and communism but to articulate a place for Japan that was both compatible with its position within a US-led order but also spoke to a kind of old discourse of pan Asianism which positioned Japan in a kind of leadership role of the region. So, Manchukuo for some of the Japanese elite played this interesting role.

So, we can see this playing out at the 8th General Assembly of the Asian People’s Anti-Communist League hosted in Tokyo in May 1962 where ex-Premier Kishi Nobusuke spoke before a gathering of former Manchurian elites, the bureaucrats, soldiers, imperial propagandists. He spoke at a kind of off the conference meeting at one of the hotels in Tokyo. So after his short remarks on the smooth operation of the conference Kishi redirected his speech back to Manchukuo giving an expansive historical take on the fate of the 14-year empire which over a decade had stood at the front lines of what he saw as an international war against Communism.

Even more interesting in my mind is the attempt to use the legacy and memory of Manchuria to recast Japan in an era of decolonisation as the true anticolonial power, one which fought against the imperialism of the western powers in the 1930s as well as was still fighting against the danger of Communist imperialism which now threaten the new independence of southeast Asia.

As we delve into the afterlives of these severed ties between Japan and East Asia and southeast Asia, we see the embers of a kind of pre-war political tradition, one which stoked the politics of anticommunism Asia well into the 19th century. Connections between Japanese ex-imperial leaders and the rulers of Taiwan, Korea, The Philippines, Indonesia were underpinned not just by shared experiences but by historical memories of total war and mass mobilisation, industrialised warfare which structured their world view and also their distinctive approach to governance well into the post-war decades.

This goes back to something, it goes back to what can be seen as a radical process of imperial ideological assimilation and military mobilisation practised by Japan within the wartime period in the 1930s which I would argue was central to the world view of a generation of Asian elites who took on leadership roles during the era of decolonisation. These experiences provided Asian elites with a shared vocabulary, one which was forged from the drill fields of army barracks in Japan and Manchukuo which linked leaders from across Asia together. Together these connections I think in both their political, their ideological and in the decades, they cover, they complicate our understanding in many ways, especially of the relationship between nationalist claims, imperial nostalgia and internationalist commitment.

We see these forces I think playing out again in the extraordinary conference of the Asian People’s Anti-Communist League held in Seoul between May 10 and 16, 1962 to celebrate the one-year anniversary of the military revolution led by Park Chung-hee. The conference was a lavish affair with massive rallies, public lectures, mass games and public plays as well as banquets. The extraordinary meeting included members from across the region including Australia and as far away seen as South Africa, Jordan and Lebanon. At the inauguration of the ceremony Park Chung-hee took the stage and in his speech, he emphasised and outlined his plans for the raising of a multinational anti-Communist army to aid the Republic of China’s military attempt to liberate the Chinese mainland.

He combined it with calls for the creation of an anti-Communist freedom centre which would focus on both fighting Communism, technological transfer and the fostering of a kind of mass cultural movement at the grassroots level across Asia, one which he imagined would build a harmonious relationship between labour and capital.

Reflecting on the first anniversary of the military revolution Park reaffirmed his commitment to maintaining military and spiritual strength and on strengthening Korea through a series of five-year plans. Park’s speech reverberated, one Japanese participant wrote in his notebook, with the traces of the songs of the Showa restoration. He prayed for Kishi Nobusuke, the ex-Premier there, he wrote two decades later in the 1980s in his final book before his death, he wrote that Park was the last true soldier of the Manchurian Empire.

So, by conclusion so Manchukuo generated imperial afterlives far beyond the Sino-Japanese relations and the industrial inheritance of the fallen empire. The memory of Manchukuo and service in north-eastern China in the 1930s created the ideological and personal connections which undergrid transnational anticommunism in East Asia from the 1950s, ‘60s through to the ‘70s. It generated mobilisations of conservatives, nationalists and pan-Asianists across the region and formed I think a key dimension of Japanese engagement with East Asia.

So of course, Manchukuo’s lasting resonance and its importance must be teased out carefully without overstating the case. Service in Manchukuo and the memory of the fallen empire were but one of many dimensions of Japanese cold war conservative internationalism. Looking at Manchukuo’s role in the Japanese cold war imaginary at how the legacies of service in north-eastern China was remembered, transformed and repurposed by the conservatives opens up I think important questions which decentre Japan’s cold war relationship with the United States and provides insights into other meaningful alignments in international communities of affiliation. It reminds us that historical memory can be martialled not only for the service of reconciliation but into a starkly different project of right-wing internationalism.

The echoes of Manchukuo, the fallen empire, are hard to trace and the way they unfold and intersect with the cold realities are complex, yet the echoes of this empire shaped not just the cold war imaginary of Japanese conservatives but many authoritarian nationalists throughout Asia.

So, I want to conclude with the following remarks. This is an image of Australians who attended the Asian People’s Anti-Communist League in the 1970s. The cold war collections held here at the National Library are invaluable reminders of the importance of the specialised Asian collection to the original goals of the Library and it serves as an unparalleled repository for Asian historical materials printed, audio-visual. By any measure the National Library’s collection ranks at the top of Asian collections in Australia. But more than that, it is the history of Australia in Asia, of Australia’s constitutive role in forging a post imperial order in Asia from the 1940s to the present. It is our own pre-history, it is the history of this country and is the history of – and it serves another purpose, it is the history of Asian views of Australia, how this country and its history was read, imagined and contested from the outside in. It is in its entirety the material record of our prehistory, the prehistory of our place in Asia. That is why when I see the collection now, I see the Reading Room where I’ve been sitting for three months. I see it empty of books. I’m left with an inescapable sense of loss. At the heart of this is the sense of farewell to the memory of Australia in Asia and farewell to my voice. So, thank you very much.

L: Thank you very much, Andrew, for that fascinating talk. For those watching who are also researchers in the field of Asian studies you may be interested to know that applications for the National Library’s 2022 Asian Study Grants will be open next Monday, 5 July. These grants offer researchers the opportunity to immerse themselves in the National Library’s collection for four weeks. Further information about these grants is available on the National Library’s website.

We're not able to take questions today but you’ll find Andrew on Twitter at andrew_levidis and I’m sure he’d be happy to field any questions. Thank you all very much for joining us today and we look forward to seeing you at our next fellowship presentation.

End of recording