Join Professor Lyndall Ryan, AM FAHA, from the University of Newcastle, as she discusses her continuing work on documenting the frontier massacres across colonial Australia. Her project includes mapping these sites, to create a historically accurate record of the Frontier Wars (1788-1930).

Mapping the Sites of Frontier Massacres in Colonial Australia 13-02-2020

*Speakers: Alison Dellit (A), Tyrone Bell (T), Sebastian Clark (S), Lyndall Ryan (L)

*Audience:

*Location: National Library of Australia

*Date: 13/2/20

A: Good evening. Thank you all for joining us here on somewhat beleaguered Ngunnawal country for this evening’s event which we are pleased to be hosting in collaboration with Manning Clark House. My name is Alison Dellit and I’m the Assistant Director General of Collaboration here at the Library which makes me responsible for Trove and the Library’s data-sharing programs. I also chair the Reconciliation Action Plan Committee at the Library.

Whether you are here with us in the theatre or joining us online tonight I’d like to welcome you to the National Library of Australia. We were approached by Manning Clark House last year to host this event because even before they had started promoting it they anticipated the very strong response that we’ve had with so many people eager to hear about this important research and we have been sold out tonight.

We are so glad to provide a space for this discussion both here in the theatre and of course online through our livestreaming. Manning Clark House is an organisation that shares many of our visions. They’re an organisation that aims to promote and encourage vigorous discussion and debate on issues of public and academic importance and they do an extraordinary job of it. Past speakers have included Chris Ullmann, Germaine Greer, Barry Jones, the Honourable Paul Keating and Sir Gustav Nossal just to name a few.

But before we begin this evening I would like to invite our own eminent Tyrone Bell to welcome us to his country. Please join me.

Applause

T: Ladies and gentlemen, my name is Tyrone Bell, I'm a descendent of the Ngunawal people and it’s my privilege this evening to welcome you to the country of the Ngunawal people. To begin with I would like to let you know that traditional Aboriginal law requires any visitors to the country being made welcome. This customary tradition has been passed on by all our generations. This ritual forms a part of our belief system, its purpose is for visitors to acknowledge whose country it is and then in turn being acknowledged as visitors and made welcome.

This welcome custom has happened for thousands of years and we use it as protection for country against bad spirits. The country on which you stand today is that of the Ngunawal people. Being a Ngunawal traditional custodian it gives me pleasure to invite you onto the country of my people.

[Speaks Aboriginal language]

In the language of my people means this is Ngunawal country, welcome to our meeting place. Please enjoy. We acknowledge and pay our respects to the elders past and present.

We call country the mother because as a mother cares for her children so does the land cares for us. This is why Aboriginal people have such close ties with the land. On behalf of myself and my people I send a warm welcome to everyone here. I’m proud to be Aboriginal and one of the traditional carers of this land. I want you to feel welcome while on our country.

Firstly I would like to acknowledge those that have come to this area for the first time and warmly welcome you. For those that have been here before welcome back and of course for those that live here please continue to enjoy. We want you to feel welcome while visiting Ngunawal country and ask that you respect the land that we have done for 60,000 years plus. So in keeping with our Ngunawal tradition and in the true spirit of friendship and reconciliation treat everyone and everything with dignity and respect and by doing so it is our belief that your spirit will be harmonised with your stay on Ngunawal country.

It is our belief that our ancestors will then in turn bless your stay on our spiritual land. May the spirit of this land remain with you today, tomorrow and always. Once again on behalf of the Ngunawal people I welcome you to our traditional country. [Speaks Aboriginal language]. Thank you and goodbye.

Applause

A: Thank you, Tyrone, for your always generous welcome.

I was really keen to introduce tonight’s event because I have admired this research work that we are about to hear about for some time. The work manages both to be innovative and a long time coming. It uses modern techniques to retell us what Aboriginal Australians have been telling us for a very long time. It is in this and other direct connections kin to Trove which is also concerned with the use of new technologies to facilitate the telling of some of our earliest and most important stories.

Here at the National Library we believe in the power of stories, history, truth and knowledge and we believe that how we understand our history will inform our future. When in the course of my work I’m called upon to try to explain the impact that historical data work can have, the work of Professor Ryan, her team and the communities who have assisted her is foremost in my mind. As a nation we cannot understand who we are without understanding how we got here and essential to this journey is our location in place and in country.

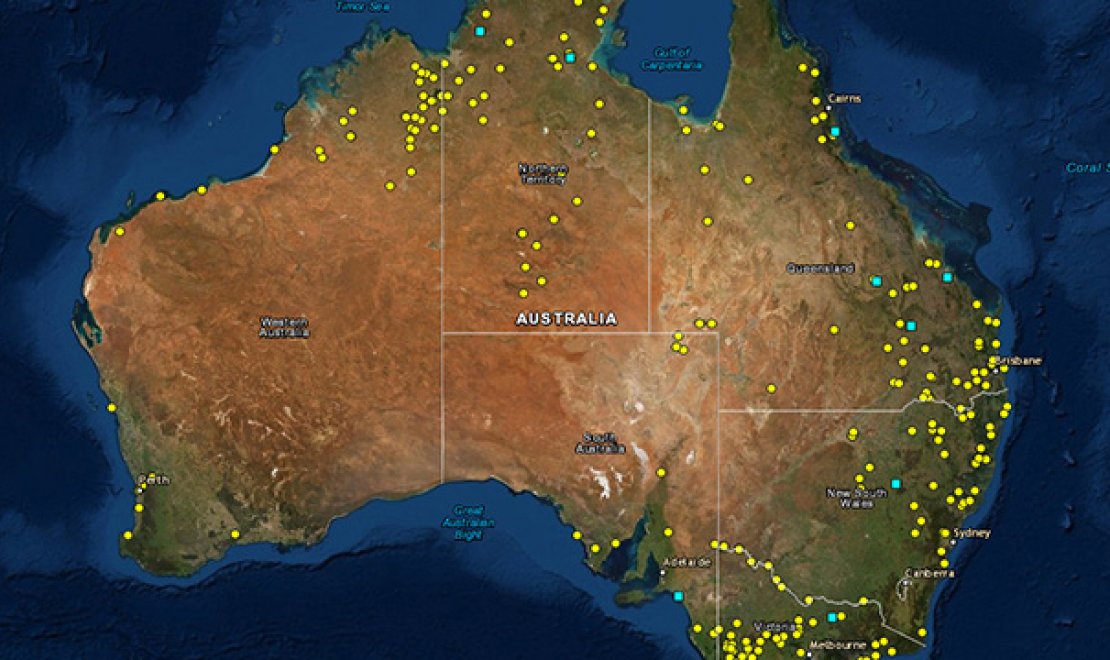

The map that you have on the screen shows us the history of our neighbourhoods, the history of our towns, the history of our continent and through this our nation. This shared understanding of our history is a prerequisite to moving towards a better future in the spirit of reconciliation and on the 12th anniversary of the Prime Minister’s apology to the stolen generations it is worth reflecting on the distance and the difficulties of that journey.

I’m sure you will all realise the seriousness of what Professor Ryan will be speaking about today but I’d like to remind you that some will find the content of this talk confronting and distressing and also that it might contain references to and depictions of Aboriginal people who have passed. As Professor Ryan and her team state on their website, this research is not a conclusion but a beginning. So without further ado let us begin. I will now hand over to the President of Manning Clark House, Mr Sebastian Clark, to say a few words. Please welcome.

Applause

S: I would like to thank Tyrone for his wonderful welcome, thank you. On behalf of Manning Clark House I acknowledge the Ngunawal people, the traditional custodians of this land on which we are meeting this evening and extend this respect to all Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders peoples in attendance today.

Manning Clark House is delighted to be jointly hosting Professor Ryan’s talk with the National Library of Australia. We thank the Library, Alison Dellit, Assistant Director of the Library’s Collaboration Branch and Library events staff for their considerable efforts in organising and making possible this important event.

Professor Lyndall Ryan is a leading academic on Aboriginal Australian and feminist history. She’s the foundation professor of Australian studies and of the Study of Violence Centre at University of Newcastle. She is well known to her commitment to identifying new forms of evidence about the past. In particular Professor Ryan has provided evidence in an interactive map of Australian colonial frontier massacres from 1788 to 1930. She intends continuing her research beyond that date. Her project recently won the New South Wales Premier’s Award for Digital History and a Walkley Award for reporting on indigenous affairs. Earlier this year Professor Ryan was awarded an AM for services to Australian historical research.

Manning Clark House and Manning Clark are very grateful to Professor Ryan for agreeing to provide this talk to demonstrate her interactive map which provides evidence of frontier war massacres of our indigenous peoples and nations. Thank you, Lyndall, you can join the microphone to your mouth.

Applause

L: Hello, everyone. I’m very pleased to be here. I’d like to thank Tyrone for your wonderful welcome to country and I intend to pay my respects to the custodians past, present and future.

In my talk tonight I want to give a little bit of a historical background to the appearance of this digital map. We’re in the third stage of the map, there’s one more stage to complete which will happen, if everything goes according to plan, by the end of 2020. I then want to show you how the map works. A number of people have said they’ve tried and failed. Well they won’t fail anymore after I’ve given you a couple of little ideas. And to give you a sense of where we think the impact that the research team would like the map to have in the future. It is very much a truth-telling project and already more than a thousand people have contacted us on the contact page. Of those 1,000 people about five have made negative comments so it’s been an incredibly positive response, people want to know, they love the map because they can see a lot of the evidence for themselves and before I properly begin I would like to say that without Trove, and here we are in the homeland, the heart of Trove, here in the National Library, my research team have said please acknowledge the importance of Trove. Without Trove this project could not have begun. So it is so important.

Applause

L: Thank you. Particularly when you live in the regions in Australia and people can’t get to the big cities, they can’t get to Canberra very often and be able to sit at your desk and click onto Trove and get the colonial newspapers and many of the other important references that are becoming digitised over time. It means that important national projects can get underway and I’d like to hope that this digital map project is one of the most important to emerge to date. It’s been such a privilege to use Trove and I just hope it continues to get more funding and that we can get more stuff up there because this is the way in which Australians are really beginning to understand their history. It is accessible to everybody, it’s not just too academic historians like myself.

So let me begin with a little bit of background. Stage 1 of the map was published in July 2017 and it had then about 150 sites on the map in eastern Australia. When I began the project in 2014 there were a number of other maps, massacre maps around in Australia. Most of them had appeared in the aftermath of the bicentenary in 1988. In that year the first national book of frontier massacres appeared by Bruce Elder called Blood on the Wattle and it was Bruce who drew our attention to the fact that there had been frontier massacres. In his book he listed about 70 massacres with important stories about most of them.

But Bruce, he didn’t publish the evidence. He had a good bibliography but he didn’t relate the bibliography to any of the particular incidents that he talked to. I have to say I’m guilty of writing a really scurrilous review of that book saying, don’t think academic historians are going to use this book in their teaching because it doesn’t have footnotes and there are no proper references. How do we know that Bruce did not make up these stories? He’s an incredibly nice guy, I feel so embarrassed now that I did that.

But the book had an enormous impact on the general reader and over the next decade, which I call the reconciliation decade, a number of wall maps appeared with dots on them and giving a list, 1 to 20 or in particular regions. There were some wall maps of the whole of Australia that appeared. I think the National Library has copies of every one of them and the most recent one I think was published in 1999 which listed a whole range of massacres and other violent incidents on the frontier but it too didn’t have the sources listed or the evidence. Of course the year 2000 was the year that the history wars broke out in the lead-up to the Olympic Games when Keith Windschuttle published a series of articles in the journal, Quadrant, where he queried a small number of massacres, perhaps some of the better known ones like Forrest River in Western Australia in 1926 which led to a Royal Commission which was inconclusive about the extent of the massacres and how many people were killed.

He also queried the massacre at a place we now call Waterloo Creek. It took place in 1838 where it was estimated in an inquiry that about 30 Aboriginal people had been slaughtered and he said that it was only three and that the whole operation was what he called a legitimate police operation. I don’t know how legitimate it is to go out and kill a number of Aboriginal people in response or retaliation to perhaps the alleged killing of one colonist. So it raised a lot of questions and it was really about the question of evidence.

Then two years at the end of 2002 Keith published his book on Tasmania called The Fabrication of Aboriginal History, Van Diemen’s Land 1803 to 1847. In that he attacked a number of historians who’d written about Tasmania, myself, Henry Reynolds and a raft of other historians in which he said that we had invented or fabricated massacres. I was very bemused by that because in that particular edition of my second edition of the Aboriginal Tasmanians I think I’ve mentioned three incidents of massacre, one at Risdon Cove which I’ll come back to in a moment, another one on the northwest coast at Cape Grim and another one in central Tasmania that I’ll come back to as well.

But Keith gave the reader the impression that I talked about 20 or 30 incidents of massacre and that I didn’t have enough evidence. It is very hard to engage in the public realm when someone accuses you of being a fabricator in that way so although I did engage I would not advise you to do so if you become the target of a media witch hunt. Don’t bother, just go for a holiday and then when the dust settles think about how you’re going to do it.

So over time I took a trip to America and I realised that there was a big debate going on in the United States about massacres of Native American people and then I also realised that there were a number of European scholars who were scratching their heads about the massacre at Srebrenica in Bosnia in 1995. That was a massacre that literally took place in plain sight but nobody saw it. It was in a little town in Bosnia, there were UN peacekeepers present. They were I think Danish or Dutch troops stationed down one end of the village and down the other end of the village several hundred Bosnians were being slaughtered by the Serbian Army.

It took six weeks for information about that massacre to come out into the public domain and it’s only in the last couple of years - I think in 2017 – that the leader of that massacre was finally convicted at the International Court of Justice at The Hague. That massacre astonished a whole raft of European scholars on the grounds that Europe was the most civilised place in the world and since the end of world war two there had been no massacres, they would never happen again. So I think these European scholars felt that their reputation as leading humanitarians, global humanitarians, that their reputation had been besmirched and so they began to do a lot of research about massacre.

Like most of us I think they thought that a massacre was a rush of blood to the head, a completely irrational act not unlike what had happened at Port Arthur in 1996 when Martin Bryant just appeared in the middle of the afternoon with all of these tourists and just went berserk with an automatic rifle. Not unlike what happened perhaps last weekend in Thailand where a young army officer shot his commanding officer and then went on a rampage in the town. It’s that sense that it’s an irrational act, it’s beyond scholarly analysis.

Well what a small group of European scholars did between 1995 and 2000 is to actually question all of that and they came to the conclusion that in fact a massacre is not an irrational act, it is a very carefully planned event and they have great intent. When that work began to be published I took a great deal of notice of it and began to realise that that could help me to understand if, how and whether there were massacres on the colonial frontier in Australia.

So with that brief introduction I want to now turn to the map and try and give some little explanation of how it works. I am not known for my technical proficiency. I rely on my research team which includes people like an e-systems architect and digital cartographers and things like that so let’s see how we can go. Alright let’s get to the front here. Okay, let’s see what we can find.

Okay you’ll see that when you get on the website there’s a little menu across the top, the home page which we’re on now and now I’ll click onto the introduction and once I work through this I’ll give you how we’ve developed a methodology to look at evidence of frontier massacre and then I’ll show you how that methodology works with a couple of examples. Then I think I will have ran out of time and I’ll be ready for questions.

Okay so the aim of the map was really to provide an Australia-wide understanding of colonial frontier massacres, set out the methodology, describe the cartography which is a technical question but there’s lots of tech heads in the audience who will know about that, give you a couple of examples and move into the preliminary findings so far.

I must say that we will never have every known frontier massacre on the map. It is an indicative map of what happened rather than a definitive map so if there are sites there that you think there should be sites there come and talk to me or fill out the questions thing at the end and I’ll see what we can do.

Okay so stage 3 has gone up in November last year and the fourth stage is in preparation and we expect it to finish by the end of 2020. We will have run out of money and we’re all a bit exhausted, we need to be moving on to other projects and that we think we’ll be ending up with more than 400 sites. I think that there’s probably seven or 800 sites, really but 400 I think makes the case.

Alright, the first thing, let’s start with a definition of a colonial frontier massacre. It is defined as the deliberate and unlawful killing of six or more defenceless – I would say undefended but the team thought defenceless was better – in one operation. Why did we choose six? Well for two reasons, one we looked at the international work on massacre and the international scholars say really anywhere between one and 10 but we settled on six because most of the massacres usually take place at Aboriginal campsites. The basic Aboriginal campsite is usually an extended family of about 20 people. You kill six people in one go, that’s 30%, that group is never going to be the same again, they can’t replace themselves so quickly. They are immediately vulnerable to instant further attack, they are vulnerable to disease because they’re not able to collect food and perform ceremonial and reproduce in the same way that they had before.

So a massacre is a pretty devastating episode in the life of an Aboriginal community. Of course some Aboriginal groups camp in larger campsites and as I go on I’ll point out how some of the massacres take place and there’s certainly of much larger Aboriginal groups. But we arrived at that and we were very much assisted in arriving at that definition by the native American scholar, Barbara Mann, who considers the killing of six undefended indigenous people from a hearth group of 20 as a fractal massacre, one that is destroying the whole basis of that particular group so that’s very important to remember.

From the international work on massacre we developed the following characteristics. It usually takes place in reprisal for an Aboriginal killing of a colonist although that colonist is killed because they have usually abducted an Aboriginal woman. So it’s usually the result of a colonist initiating a practice which is absolutely outside of Aboriginal practice but what is recorded in the literature of course is the Aboriginal killing of the colonist or the taking of livestock or whatever. So it’s all seen from a colonial perspective, not from the Aboriginal perspective.

Secondly it’s a planned event. The perpetrators need to collect the weapons they’re going to use to kill people. They must make sure they’ve got enough ammunition. They might be taking cutlasses, they might be taking Brown Bess muskets, they might have some pistols, it depends on the historical period. The Brown Bess musket is in widespread use across the colonial frontier in Australia right up until 1860. It is the key weapon. If other historians say oh it was hard to load, it had powder in it and it often misfired and the pan didn’t work and so on they certainly managed to kill a lot of Aboriginal people, don’t fall for that.

It takes place in secret. This is a critical characteristic of massacre generally. It’s a planned event, it is a completely illegal event. Why would you tell people you’re going to do it? The perpetrators are sworn to secrecy and no witnesses are planned to be present, that is, the witnesses who are the victims are meant to be all killed. This doesn’t always happen and we’ve got many stories of how little children survive. Their mothers hide them in a log or put them out of sight, they see everything that’s going on, they miss being killed. So they are witnesses but they cannot speak at the time for fear that they will be killed by the perpetrators. Secondly of course we know that until 1875 in New South Wales Aboriginal people could not present evidence in court so the perpetrators have got a lot going for them.

So it takes place in secret. Sometimes however something gets out in the press and this is where Trove is very helpful. Somebody might write a letter to a friend in a very anonymous way or something happened down over there 10 miles down the road, we think Aboriginal people were killed. There’ll be instant denial, the perpetrators will come out and say nothing happened and I’ll give you an example of that very shortly.

The assassins and the victims often know each other, it’s a very intimate event. Not in every case but often that is the case. It’s where colonists have arrived in an area to take the land. They do meet the Aboriginal people living there and then relations break down and that’s when the massacre happens. So they know where the Aboriginal people are camped, they know the names of some of them if not all of them so they’re killing people that they know. So this again is something as Australians we have to understand.

The purpose is to force them into submission or to eradicate them entirely and some of the big massacres, it’s about eradication. It is generally confined, a massacre, to a particular geographical space, a campsite on the river, in a rock ledge or whatever. It takes place over a limited time period. That’s certainly the case in the 19th century but as we move into the 20th century and look at some of the massacres in the 1920s such as Forrest River, Coniston in 1928 we find it takes place over a period of weeks and the Aboriginal people are driven forward and then they might kill people and then the perpetrators go back and get fresh ammunition, fresh horses, they’ll come back and have another go.

Coniston took place over a period of weeks and the Warlpiri were driven out of their country and many of them have never returned so that is a really frightening account. So this geographical space is certainly there say in colonial Tasmania and Victoria, parts of Queensland and South Australia but less so I think in parts of the Northern Territory and in the Kimberly and I’ll talk about that.

I’ve talked about those that take place over a wide area over several weeks. The important thing is that no matter when the massacre took place a code of silence is imposed which makes detection difficult and this is where the historian has to really get into the sources and try and work out fact from fiction and as historians we’re usually trained to consider the evidence or the sources that appear closest to the event to give those sources the greatest status.

What I’ve learned through massacre, it’s usually the later evidence that gives you a better idea of what happened. So it’s a bit like turning a lot of your historical training on its head and I think that’s been one of the hardest things for me to come to terms with. So the most reliable evidence, a massacre is often provided by the witnesses, perpetrators long after the event when they’re no longer threatened with arrest or reprisal.

Okay, the project has worked very hard to collect published evidence or evidence that’s readily accessible either online or in books or newspapers and again Trove has been an incredibly important source of evidence of massacre. We wanted to use sources that the person using the map or accessing the map could use themselves, could go and find themselves. If they didn’t believe what we’ve put on the screen on the map then they can go and read the sources themselves and they might end up with a different interpretation.

We wanted to encourage people to use the sources, to go and investigate themselves and see what we’d found and so we’ve just listed the kinds of sources that we’ve generally used. There’s the very conventional sources like Historical Records of Australia which is now online at last, thank goodness but we’ve also used another wide array of travel guides, from people visiting Queensland for example. So oh I visited this town and met the perpetrators coming back from a massacre and you go oh okay and so you’ve got something to chase up.

We've also got many published accounts from Aboriginal people, interviews. As soon as the tape recorder was invented or arrived in Australia anthropologists were out there interviewing Aboriginal people. Many of them were being published in articles, books, journals, all kinds. Published Aboriginal sources are much richer than we realise and they’re really fantastic and of course there’s important evidence that appeared before Aboriginal land commissioners and native title tribunals. So the array of Aboriginal evidence is becoming greater by the day. We also know that Aboriginal people have used their own forms of evidence like the Aboriginal massacre paintings from the Kimberley are an incredibly rich source because the way they tell the stories of how the massacres happened and that’s very important as well.

So there’s not really a typical massacre but often there’s a little story in a newspaper on Trove and it might give you a name but it might give you a place, it’s something to follow up in other kinds of sources. It’s not to say we haven’t used archival sources but in many cases the archival sources are official sources and they’re about covering up. The sources for the Kimberly massacres for example are largely carried out by joint operations with settlers and police. The police have to write a report. The reports, we collected 500 rounds of ammunition, we went out on a patrol, we came back and we didn’t have any ammunition left.

Sometimes the odd police person or the odd settler might keep a diary. We went out, there were eight of us in the group, there were four police, four of us, we made sure we had fresh horses, we were out for two weeks. We shot down two Aboriginal camps. In the first one probably about 50 give or take. We were particularly looking for a particular Aboriginal guy, warrior and not sure that we got him so we went to the next camp and we think we got him in the next camp and we shot a lot of women and children there.

It's that kind of evidence that you’ve got to work with and then you think well exactly where was that camp? So it takes a long time. We’ve got a lot of unfinished work sitting back there because we can’t actually identify where it took place or we’ve got others where there’s not a clear date. We like to have at least a year, 1897. We’ve got a couple where we’ve had to say the 1890s in the hope that someone will contact us and say that happened in 1896. We do a lot of background reading about when that part of the Kimberly was opened up. Who were the key people who opened up the Kimberley? What were they doing at any one point? When did the police parties arrive? We can do a lot of background work for context and that takes time too.

We’ve got a wonderful historian, Chris Owen, working with us now who’s based in Perth but has written some wonderful work on the Kimberley. There’s been some other wonderful researchers in the Kimberley in the 1980s and 1990s who have been incredibly generous in giving us all their research too so it’s an endless jigsaw puzzle, putting things together.

We also established a typology so what we’re looking for for basic information which I discovered was necessary if it’s going to end up on a map. I had to learn all about various ways of collecting data, you just couldn’t put it in the way that I used to collect data. I can’t do that anymore. As a historian I have to behave like a social scientist. It’s been very painful. I have to do things like the weapons and people have written to us about the weapons and we need to be more upfront of exactly describing the weapons that were used. There’s a lot of weapons historians around the world who have been very anxious to help us there.

Then we’ve got into the cartography area about the full collection of sites is stored, blah, blah, blah, points showing massacre, blah, blah, blah. So one of the other points I’d like to make is that when we click on a dot you don’t get the actual site. If for example a massacre had taken place in the National Library of Australia you will not get the National Library of Australia appearing on the map. It will show the whole surrounding area, probably the whole of Lake Burley-Griffin, the suburb of Parkes and possibly going into Griffith simply because Aboriginal people – well there are two reasons. First is that many of the very well known sites have been desecrated. Aboriginal people don’t want more of that desecration to continue so giving a general idea of the site rather than the actual site is much better.

Secondly for many Aboriginal communities a known site is a sacred site, there could be human remains there and they want those remains to be respected. So I’d like to hope that the people using the map are not going to rush out and say oh I want to find that site and dig and find something and see if I can find a bone. Australians actually don’t have a very good reputation for respecting sites, we know that about Uluru. There's a sense that it’s our country, we can do anything we like to it. I would like to hope that we’ll start taking a different approach and understanding and respecting sites that are there and even if you're not going to be able to find a bone that you're not going to go ‘round digging it up or doing other things to it. So learning this project is much about learning respect.

So I’ll just give you a couple of preliminary findings. We found that in the early days from the first massacre in 1794 on the Hawkesbury up to 1826, both in Tasmania and New South Wales, the massacres are all carried out on foot. Horses were not widely used in early colonial Australia, they weren’t widely available and they were usually carried out as a night-time attack on an Aboriginal camp.

After 1827 in New South Wales and the other colonies, apart from Tasmania, the horse is king, the horse is the way in which the perpetrators get to a site, get to a place where they’re going to carry it out. We have no examples of them being carried out from vehicles, they’re carried out on horseback. As the weapons in the 19th century improve they’re designed to be fired from horseback and those weapons change in time and I think that’s important to know.

Once a horse is used you can get probably more people in a group of perpetrators. In Tasmania you might get a group on foot that could be between 10 and 20 people. Once you’ve got horses you can get a group of 20 people on horseback and inflict a lot of damage.

Okay so just briefly we’ve got 311 on the map at the moment, 37 for Tasmania, Victoria 54, 83 in New South Wales, Queensland 42, obviously very under-researched. South Australia, 44 and that includes sites in the NT. You have to remember - you learn your history - when the Northern Territory was opened up in the 1860s it was of course part of South Australia so when there are only six in the Northern Territory most of those would be for what we call South Australia and we’ve now got 34 in the west. Stage 4 will have at least twice that number and the same for the Northern Territory. We think we’ll end up with probably nearly 100 in Western Australia and nearly 100 in the Northern Territory and probably nearly 100 in Queensland so the northern part of Australia is the real story of frontier massacre.

Okay let’s get down to business and get back to the map. Okay. I just want to give you a couple of examples of how the map works. It’s interesting looking at the massacres in Victoria, there are many more than we thought and we’ve had quite a considerable number of people from Victoria contacting us since stage 1 went up with more information. We did have a lot of information about massacres in Gippsland but we’re now getting more right up along the border with New South Wales, more along the Murray which is understandable because it’s a major water course.

But you’ll notice that there’s very few along the Darling River. It’s not because they didn’t happen, it’s because we don’t have strong enough evidence to meet the criteria to get onto the map. We have a lot in north-eastern New South Wales, southern Queensland. I’m still trying to fill in this area here. You can see there’s a lot in the Kimberley. I think we’ve got about 20 more to put in from the Kimberley and there’s more from the southwest to go in. South Australia, probably a few more around here.

So I just wanted to give you a couple of examples of how we’ve been working out with the massacres and I’d like to start with this one in Queensland called Battle Camp which took place – we’ve actually got a day – on the 5th of November 1873 in the early morning. That’s important with these people.

Okay so that’s when you click on. Oh, why are the Aboriginal sites all in yellow? Aboriginal people that we contacted both at AIATSIS and various Aboriginal study programs and centres in Australian universities said yellow was the best colour to use. We want red of course but no so yellow is the colour. So sorry, I’ll get back to that.

Okay this is Battle Camp, it’s on the road, the track between Cooktown and Laura which was where gold was found early in 1873 and it was immediately opened up and miners caught a ship from Brisbane up to Cooktown and wanted to set off along the Palmer River over hill and dale to get to Laura where the gold mine was. Laura actually operated for about 30 years but it was the first five years where the biggest payload happened.

Okay. What we find is that a shipload of miners arrived in Cooktown and the local magistrate was very worried about letting this group. I think there were about 40 or 50 in the group but I haven’t got an actual number but there was enough of them to put pressure on the Magistrate to say we’re going right away, we’re not going to wait until you can say it’s safe for us to go, we’re going now. So there were a magistrate and another senior officer there and so they found themselves having to lead this party of miners on the road to the Palmer River goldfield and it took about two weeks to get there. It’s only later that you realise they’re also joined by a detachment of native police and the massacre took place at a lagoon early one morning.

How do we know? Well somebody in that group, unnamed, writes an article in The Brisbane Telegraph on the 22nd of January 1874, a couple of months later so let’s have a look at the article. Isn’t Trove wonderful? You just click and there it is. Now when you’re out there in the bush and you just click and you're right into it. Here it is, the Palmer. So it’s dated the 17th of November, it’s a letter. My dear friend, we arrived here at the Palmer all well yesterday and so on. We left the Endeavour River, Cooktown, on the 30th of October – 31st of – and some came 10 miles over broken granite country, camped at a creek, blah, blah, blah which we christened after one of the black boys. Isn’t that wonderful? In other words one of the guys in the native police. You really have to read – it took us weeks to understand this. When 15 miles and were joined by the police, surveyors and Commissioner. Mustered about 110 souls altogether. The party gets bigger. Only three-and-a-half horses. I don’t know what the half horse was.

Camped on Oaky Creek, went fishing and shooting, plenty of water, a tributary of the Johnston River running southeast, camped – so it’s a running commentary of a diary. November the 2nd, went up Oaky Creek, heavy travelling, camped on a branch and so on so it’s quite an intimate account. Then November 3, started over the spur of the range running east, came to Normanby River, 15 miles started – meaning startled – a mob of blacks. Shot several and it goes on and then the next morning they decide to attack the camp at dawn and kill a number of Aboriginal people.

So this is reported in The Brisbane Telegraph so it’s raised in the Queensland Parliament, what’s going on here? Not even the Queensland Parliament was very happy about this because it then goes into the Melbourne press, it was reproduced in The Argus and then picked up in The Adelaide Advertiser and before you know it it spread across Australia, massacre, Battle Camp Creek. So the Queensland Parliament – the Premier authorises that there will be an inquiry and sends a magistrate to Cooktown to follow up this group out to Laura and interview people.

The Magistrate interviewed 15 people, miners, he named them and they all said nothing happened, nothing, no. This is a fabrication, this is a made-up story. This story in The Brisbane Telegraph, it didn’t happen, nothing happened. It was very interesting that the Magistrate did not interview the other magistrate or the Chief Engineer or anyone from the native police. So he lists the names so the whole story dies.

So we have to fast-forward about – in 1922 Robert Logan Jack who was a local historian in Queensland included an account of the massacre by Billy Webb, one of the 16 miners interviewed by Hamilton, the Magistrate. Webb recounted that on the 5th of November a large group of warriors approached the party and the men on horseback shot at them until they ran away. Then in 1937 – this is considerably later again – another miner, J J Hogg, who’d also been interviewed by Magistrate Hamilton way back then in the 1870s prepared his account of the massacre and published it in 1937. He said that the leaders of the party surprised a large encampment of Aboriginal people preparing their breakfast and shot them all. The journal of a member of the party was later placed in the John Oxley Library and the journal said November the 3rd and so on, it goes on. The blacks surprised us then we surprised them the next day.

So this massacre, the information comes out literally decades later. It’s very hard for historians to come to terms with this because normally I would have thought the Magistrate’s report, if he didn’t get all the information then, what’s going on? The fact that the Magistrate did not interview the other magistrate, did not interview any of the senior officers, did not interview any of the officers leading that native police detachment, we have to ask why. These miners were ordinary men and they all said nothing happened.

So it’s interesting however that there is this need to tell even if it’s decades later. So the story obviously never went away and it is clear that something happened. So that’s an example of where the initial story appearing in Trove gave us something to follow up and it’s extraordinary in that way.

Let me give you another – just hang on a second – just a couple of others to indicate what happened. Okay, let’s go back to the map. Let’s see if I can find the Forrest River. Is this in here? Oh we’ll look at Mowla Bluff, that’s a good one. Mowla Bluff took place in September 1916. It’s where a group of Aboriginal people were massacred by a police party as a result of I think a prospector being killed because he’d run off with an Aboriginal woman for the wrong reasons. So we’ve got the full story, it’s a long situation.

This is largely information that has come from the Aboriginal community because they felt the story that had been reported in the police records was completely wrong so they made a film about it called Mowla Bluff and the film was made about 10 years ago and it’s been shown a lot around universities and so on. It’s been made by the Aboriginal people themselves where they interviewed people and they reconstruct what actually happened so this is a wonderful story that is getting on the map, one of complete denial by the perpetrators. This is one where witnesses speak out later, it becomes a very important story in the local Aboriginal community and so powerful that they make a film so that’s a wonderful example of where you get Aboriginal evidence that has been passed down over the generations. So let me go back.

Just one final example and perhaps I’ll go to one of the ones in Tasmania which I was hauled over the coals for which is this one. Okay, this is called the Elizabeth River and an alleged incident took place there on the 12th of April 1827 at dawn and so let's have a look at what it says. So again Trove comes to the rescue, these are Tasmanian newspapers. The Colonial Times reported that three weeks earlier two shepherds, really, of a settler at the Elizabeth River had been killed by a party of Aborigines led by the notorious Black Tom [Kickett-Apolla] 55:45, a new biography’s coming out any moment of him, he’s fabulous. Anyway several persons assisted by a small party of soldiers made immediate pursuit and then that’s it, that’s all you get, that’s all you get, immediate pursuit.

Then there’s another story that appears in the other Hobart newspaper, The Hobart Town Gazette, and it’s a story written by the leading military soldier that was out there and how there was only half a dozen soldiers and they were confronted by this huge number of Aboriginal warriors bristling with spears but the soldiers were able to get away by hiding behind trees and negotiating their way out. But they managed also apparently to find the Aboriginal camp and bring back all the spears and other trophies. Then there’s another letter, a letter that appears a week later saying this story’s completely fabricated but gives no further information so it just sits like that.

Then my attention was drawn to a journal in 2000, a published memoir of the settler, James George, who was a young man at the time, recorded the incident in the following way. Having seen their fires in a gully and knew the river, some score of armed men, constables, soldiers, civilians and prisoners or assigned servants who fell in with the natives when they were going to their breakfast. A dawn raid. They fired volley after volley among the blackfellows and reported killing some two score.

That was published by the local historical society in 2002 but it’s based on his memoir that he’d written some years before, some member of the family found it so that of course is gold, you don’t always get that information. So this sort of incident where they’re being attacked by Aboriginal people, in fact it’s this armed party who are attacking the Aborigines in their camp at dawn. No wonder they’re coming back with all of these spears and trophies and other things like that. So just finding that diary that had been published was wonderful for me, that was great.

We do have a sense of the site which is probably we think around that dam at the moment. I was at a conference earlier today talking about water and how so many of the possible sites where Aboriginal people may have been killed have been turned into dams or lagoons or reservoirs, a lot along the Murray, a lot along the rivers going from Victoria, something we need to explore a lot more. I’m hoping that the data on the map can help us to do that.

Okay, I’ve given you a couple of examples of how the map works, I should wrap up now and see that we can draw, some conclusions. Okay so let’s go back to the introduction. The map is very good, it’s fine but as a historian I love the timeline because it lists everyone in chronological order and there it all is and for me that is just fabulous so along by date and if I have to make any changes I can. The changes don’t appear.

Let's go back to the introduction and look at some other preliminary findings to date. The findings have changed a little bit with each stage so these are only preliminary findings. One’s about the numbers and so on. Who were the perpetrators? Well I began the project thinking that most of the perpetrators were probably local settlers and their employees, the shepherds and so on. At Myall Creek for example it was an opportunity massacre led by a local settler and surrounding stockmen.

But what we’re beginning to find is the police, whether they’re native police or mounted colonial police or whatever, are more likely to be there. The arms of the state are particularly, as time moves on, particularly as we move from the late 19th century into the 20th century the arms of the state are more likely to be involved than I realised. They’re often operating what I call in a joint operation where the settlers and the police are working together. So this is not something that the state did not know about, I think the state is very much involved in the massacres in the first 20 and 30 years. They see themselves as patrolling the frontiers of the early settlements and they’re British soldiers who are largely out there.

From the mid-1820s the British soldiers are employed as mounted police, the horses and equipment are paid for by the colonial government and then I think the last time we’ve got actual soldiers from a British regiment working on the frontier is in southern Queensland in 1841. That particular British regiment, the 99th regiment, was then sent to New Zealand and fought in the New Zealand wars of the mid-1840s, they come back to Australia, they’re deployed to Tasmania likely to guard the convicts but they’re also sent to Melbourne to quell the riots following Eureka Stockade in 1854. There’s some sent over to Perth where there’s some riots going on there so these British regiments have a role in many of these frontier massacres up to the early 1850s. So again that’s a lot of new work that needs to be done, nobody’s really sussed that out. I do know that the first genuine war memorial is in Hobart erected in 1850 by the soldiers in that 99th regiment in honour of their comrades who fell in the New Zealand wars.

So we’ve got connections with frontier massacres and the New Zealand wars, that’s got to be understood. We also know in the second lot of New Zealand wars in the 1860s, the regiments are starting to deploy some tactics that the perpetrators do in massacres on the Australian colonial frontier. They’re on horses and they’re in what they call flying columns but we can see these are colonial wars and the same strategies are being used on the colonial frontier right across the British Empire.

So what is happening in Australia is not unique to Australia, it is part of gaining an empire and conquering an empire and gaining land. So we have to look more broadly at what a map like this can tell us, who the perpetrators were, how the Aboriginal people were killed. We also have 12 sites of where Aboriginal people have killed colonists which is also important and all of those incidents have been well and truly written up in many, many books and so on. I’ll just get back to the map. We've also got an Aboriginal massacre of Macassans up here, this little green triangle is where they killed a group of Macassans who broke some protocols. So this is a frontier war, it lasted for a very long period of time. It is the story of colonial Australia and massacre is a key feature of those wars.

The final question, what percentage of Aboriginal people estimated killed? What part did massacre play? I can only give examples from Victoria and Tasmania and in Victoria for example we think that the massacres were responsible for 60% of the reported deaths of Aboriginal people on the frontier. In Tasmania it’s closer to 70% so massacre is a critically important strategy. It’s quick, it’s well planned and you get a result. I think I’ll stop there, thank you.

Applause

End of recording