Join Paul Sharrad as he explores some of the delights found while researching Thomas Keneally's papers, including the forgotten highlights from his career.

Paul will explore the conditions under which writers in the 1960’s and 1970’s worked to survive, and how writers fit within the drive to create a national culture. How does a writer attempting to create a living from his work assemble a long-lasting career in negotiations with editors, agents, reviewers and markets?

He will also question what the place of the writer who becomes a public celebrity is, and how 'middlebrow' writing is valued.

26-02-2020 Thomas Keneally's Career and the Literary Machine

*Speakers: Paul Sharrad (P), Nat Williams (W)

*Audience: (A)

*Location: National Library of Australia

*Date: 26/2/2020

W: Good afternoon. Thank you all for joining us for this afternoon’s event. My name is Nat Williams and I am the Treasure’s Curator within the Community Outreach Section here at the National Library of Australia. Whether you are here with us in the Theatre or joining us online, welcome to the National Library of Australia.

As we begin, I would like to acknowledge and pay my respects to the Ngunnawal and Ngambri people, on whose traditional lands we meet today and whose culture we celebrate as one of the oldest continuing cultures in the world. I pay my respects to elders past, present and emerging, for caring for this land we are now privileged to call our home and on which the National Library of Australia stands. I would also like to extend my respects to any First Nations peoples who are joining us this afternoon.

So in the meantime please let me join you in welcoming Professor Paul Sharrad to the stand here to let him talk to you about the wonderful time I’m sure he had in Keneally’s archive.

Applause

P: Good afternoon and thank you for coming. Thank you, Nat, and Nicole for the introductions and I too would like to acknowledge being on Ngunawal country. If I can get out of this particular visual.

So I thought I would spend the next 40 minutes talking a little bit about why the project began, what’s in the book and the nature of the literary career and if there’s time finish up with some gems from the National Library collection that I managed to ferret out. It was a case of ferreting out because it was a huge mix of everything Tom ever shoved in a box. So this is the book and thank you very much to the National Library and various other libraries for indulging me in travelling through a whole lot of paper and bothering a whole lot of people who were all extremely helpful. Also thanks to the Australia Research Council who funded some of the trips to libraries to get the material.

So what started the project? Well looking around most of you probably had similar experiences to me where when you were doing undergraduate studies there wasn’t a lot of Australian material being taught. In my case I was still becoming a junior lecturer in a place where the professor was telling me there was no Australian literature and what there was he read on the plane out and that was D H Lawrence.

So a lot of this comes from a kind of similarly national culturalist background, I suppose, as Tom’s although Tom’s a good deal older than me, that it is a tracking of an engagement with national history and the building of national culture. Through the 1960s, which is when Tom began his literary career, when it is worth remembering there were no formal literary agents in Australia at the time, that Thea Astley, Patrick White were just coming onstream as the new wave of Australian writing replacing people like the romantic realists like Eleanor Dark and Kylie Tennant and so forth. That there was a huge shock if you like which some of you may well remember when White and Keneally and Astley first came onstream as stylists, as people interested in metaphysical questions. That the field of Australian literature was not established as a formal body of study.

We had had literary journals around since the 1940s like Meanjin but it was still the case that until the late ‘60s there were no professors of Australian literature. So Tom was coming into a field that as a novice he saw as very much a vacant lot and a vacant lot in which it was still, as Henry Lawson once said, extremely difficult to make a living as a writer. His advice was to look in a mirror and shoot yourself or go to London. Part of Tom’s strategy eventually involved going overseas which of course carries with it its own particular struggles and issues.

But this is simply just to explain this one, this is the Commonwealth Literature Fellowship which was originally a pension for old and indigent writers, it was transformed in the ‘30s as a way of promoting Australian literature. If you won one you had the job of going around to country towns giving lectures about Australian writers and these are the old gestetnered sheets advertising Tom’s trips around the north of New South Wales, part of which of course set him up for discovering the story of the Governor Brothers which became Jimmie Blacksmith. But it was very much a kind of amateur do-it-yourself project in developing Australian literature at the time.

When Bring Larks and Heroes came out it was taken as, to quote one reviewer, the great Australian novel. In this case it’s Max Harris saying I’ve collated the reviews and modest Thomas must surely be reeling under the machine gun stutter of superlatives.

There was another letter in the files upstairs from Charmian Clift saying I wish you 100 shire granddaughters, hedges bursting with larks and as many heroes as you can sing. I am ravished, oh sir, we have been waiting for you. So it was the publishing event of 1967, it was at the time. As one of my colleagues slightly younger than me said the reason she’s a literary lecturer today is because she was so enthused by reading Bring Larks and Heroes in her honours year of study.

So he goes on of course to become the writer that Australia could no longer ignore by winning the Booker Prize, the local boy makes good etc. But following that there does become certainly from an academic side of things a sort of wondering about whatever happened to? Which is kind of ironic because – and this is part of what the book explores – here we have somebody who everybody knows, everybody’s seen him on television, everybody’s heard him on radio, he’s in every second newspaper having an opinion on something but in terms of scholarship, in terms of teaching of texts and so forth there is a sense that he has faded from view.

Just to an interesting experiment this is probably a self-selecting audience which is going to prove me wrong. Hands up those of you who’ve read some Tom Keneally. Okay. Hands up if you’ve read something more than Schindler’s Ark. Alright. Hands up if you’ve read something more than Schindler’s Ark and Jimmie Blacksmith. You know we’re starting to thin down. I did a survey of two writers’ festivals in fact, obviously across a slightly less self-selecting group than is here and across a wider range of ages and apart from Schindler’s Ark and Jimmie Blacksmith it was remarkable how few people had read any Keneally even though they all knew who he was which is part of what got me interested in looking at the nature of his career. To quote one other of my academic colleagues, when I was spouting forth about the joys of Tom Keneally, he leaned back at the back of the lecture theatre and said who would want to read Tom Keneally? Which I think was typical of a certain academic hauteur in relation to somebody who was seen as being a popular writer.

What then became interesting to me in looking through the collection of papers with his publishers, the papers upstairs which are full of his royalty slips, is that he’s not actually as successful in sales as one might think but nonetheless he has persisted over 50 years of producing almost a book a year and sometimes three books a year. So what is the nature of this career? How does it work? How did he survive becomes what the book is actually about. So it’s about the shape of a career, it’s about the nature of a literary career, it’s a mixture of literary criticism, literary history, literary biography, none of those three and all of those three plus as the title of the book suggests it’s about what we can loosely think of as the literary machine. All those programs and subprograms and routines that mesh together to produce novels in this case and plays and films which is one of the points about his career, it’s not just as a novelist even though we all know him as a novelist.

So what is the shape of the career? What are the factors that influence it? One of the things is obviously personality of the author. Tom talks about himself as being impulsive and he says it’s the thing that gets the books written. It’s also the thing that perhaps makes the books not necessarily as perfect as some critics might like them to be.

He's a person person which informs his love of colourful characters and some of you will have read his histories, The Australians, and the point he makes in that is that Australian history might be boring but Australians aren’t, they’re full of colourful characters and that’s what drives a lot of his literary interest. So that he writes a book for example called The American Scoundrel which is based on a civil war era personality and managed to shoot somebody in public in Washington and get away with it and lived a very colourful life in the process.

As a people person he’s also very loyal to his friends and sometimes that’s got him in trouble across his career as it clashes with the machineries of the impersonal side of publishing. One indication of how he is the congenial person, chap that his public image is, is a book called The Utility Player. Anyone read it? There we go. See we’re in Canberra, we’re not in New South Wales. Tom, as many of you will know, is a sports fanatic, a number one cardholder for the – what is it? Anyway, some rugby team - I was born in South Australia – rugby league and one of the players in his team at the time was Des Hasler. Des went through a slump in his career at some point and Tom basically wrote his biography, published the book and gave half the proceeds to Des.

So it’s that kind of personality which influences many of the choices across his career. This intersects obviously with agents. Again as a person person he gets on very well with a lot of his agents, they become family members almost. He’s devastated when they die in a couple of cases and is forced to move often to another publisher at the same time. He got a lot of flak, particularly from people like Patrick White as being disloyal, ungentlemanly etc, etc but looking at his career and the way he thinks and the way he reacts to the professional side of things very much explains some of the shifts across that career.

As I said there were no agents when he started writing, he was his own agent. That got him into a lot of flak as he starts to realise that most publishing went through England, that his first publisher, Castle, only had a local department here where it was run from London, that his royalties were a cut rate of what sales he would get selling in England and so forth so he becomes very politicised if you like in cultural terms as an Australian writer working across at least at that point two markets and fights for his rights.

The publishing culture, obviously once you move across two cultures or even within Australia at the time is part of the machinery. That there was a sense of loyalty as an Australian writer that you’ll publish with an Australian publisher. That of course could have a cost in terms of how many people you would reach, how many sales you might expect. Most publishers worked as I said through a London central office so he’s already, whether he likes it or not, involved in two venues for publishing to audiences and there are different cultures at the time, both within Australia and across to England, England very much the old handshake gentleman’s agreement kind of publishing, lunches etc. As he has his own rights to America he’s also looking to get more readers, many more readers in some cases, in the States but the culture in the States is quite different, it’s much more marketing-orientated.

So at some point he says to his English publisher I’m in America talking to my publishers there, can I come over and I’ll do a few signings for you? There’s this sort of rather Brittanic response, oh dear boy, we don’t spend money on such things, it’s the reviews that sell books. Well part of the publishing industry obviously changes, he is caught up in those changes and sometimes he wins because of that shift to a much more marketing-orientated publishing industry. He does probably well in America because of that. He starts to get disaffected with his British publishers because of their old guard if you like attitude to publishing. His common feeling is that they’re not marketing him well enough, that the reviews say he’s great but the sales don’t indicate that.

The other thing that comes into play is the very mechanical thing, and sometimes the authors don’t have control of this themselves but covers. Covers can sell books, they can kill books. This book was The Playmaker and this was a draft for the cover of one edition. This was the sketch for the British edition. As you can see it’s very much playing with a sort of 18th century look and we never quite knew what the iguana was doing in the front of the cover but very Gothic. You can see there are hangman’s nooses in your top right corner and so forth. It came out looking like this from England. Tom was pretty irate. He said it made it look like a dress-up Georgette Heyer historical romance which is exactly what he wasn’t trying to do. This was the compromise that came out in Australia where he took the original performance of The Recruiting Officer, the first play staged in Australia and covered up some of the illustration.

The other problem was that – as you can see from the text there – he was trying to allegorise it or mythicise the founding of Australia as a kind of space trip that as he put it in 1788, founding a colony in Australia was a bit like the moon landing, it was the other side of the world, it had been unexplored etc. So he didn’t really want his story to be visibly set in Australia and certainly a cover like that blew his cover as it were and he wasn’t very happy about it.

The other thing is that his Collins publisher, again from a British sense of what was literary, marked the literariness with these rather bleak, probably not very attractive in the bookshop, covers. So small mechanical decisions like this could affect the literary career and certainly affected his from time to time. But you can see how these would have positioned him as a literary writer when in many cases he was moving to a much more commercial side of producing writing and being hit over the head by certainly academic critics for producing far too much, far too often, far too quickly. So he’s playing between that idea of commercial identity and literary identity.

Eventually he’s marketing across three major countries and that causes all sorts of problems so that at one point if you look at the manuscripts upstairs he’s going through the copy edits from I think it was one of the Collins editors who’s asking questions, does this mean such-and-such? The annotation is guess, you pommy fuckwit. So that kind of clash and equally with the American publishers as well who were demanding more explanation of what all this Australian stuff is or this novel doesn’t have enough American characters to sell etc, etc. So how do you juggle those three different sets of demands on you? Of course the Australian audience are saying you have to be Australian, we need Australian language and so forth, stay loyal to your own country.

So the other things you can take into account are things like technology. If you look at the papers upstairs you get a history of writing technology. He starts as an indigent person, kicked out from seminary with no job, writing on scraps of paper in pencil and biro, on foolscap and scrapbooks, on the back of school examination papers when he became a teacher. Eventually he hires a typist who’s still working with those old blue carbon copies. You could see all the telegrams that flow to and fro and if I were talking to undergraduate students they would say what’s a telegram? With no idea of how costly they were, how things could go wrong. A lot of his career is in fact mapped by mail going astray, it reads like a Victorian novel sometimes so that while he’s arguing the toss with one of his agents it turns out that the agent has just died and the letters cross in the post and so forth and this causes understandable ructions at both ends.

So there’s that and then the fax machine comes into play. At this point in the ‘90s he’s teaching in America. He’s also holding down a position on the Literature Board of the Australia Council, he is becoming President of the Australian Republican Movement. That would be not be possible without the fax machine. So certain career changes open up simply because of technology. Eventually he takes on Dictaphones which of course help him to produce the rapid rates of novels that he’s famous for but it doesn’t solve everything. He has a secretary in his American university who’s typing his manuscripts from Dictaphones. The American sense of his Irish-Australian accent produces some very strange copy so he doesn’t really save time because he has to go back and correct it all. So there again this is the mechanics of making what we don’t see as the overall literary career.

The other aspect of his career is of course he is known for his politics. He’s very much been a New South Wales Labor man. He is actually in that photo if you look for the black-rimmed glasses and the bald head, he’s there at the Bankstown launch for Gough Whitlam’s election campaign and eventually he becomes as I said the President of the Australian Republican Movement, deliberately picked by politicians because he was a cultural figure, not a politician, supposedly a neutral figure. But I mean in terms of a literary career this creates interesting challenges. Once you put your flag up like that you possibly halve your audience and certainly he got a lot of flak in reviews from America when he was perceived as being anti-American in his politics. In Australia you could also bet that Quadrant would give him a pasting whereas something like Sydney Morning Herald would give him a good review and so forth so it was a risky strategy if you were trying to be a successful writer but it’s one that he managed across as I say 50 years with some degree of success.

Reviewers obviously play a part in the literary career and what’s become interesting to me is looking across the range of reviews across different countries. He went public various times in Australia complaining about the treatment he got from certain selected reviewers particularly and that created a big media debate, of course, who were saying what’s he complaining for? Why doesn’t he just toughen up? He should be more Australian, not worry about his overseas market etc, etc or he should just damn well write better and if you look at the reviews it’s very clear, that he complains with some justification about Australian reviewers. That if they are agin him, they are agin him in a much more personal and vituperative manner than the British who are agin him.

So there is a culture of reviewing if you like where the gentleman reviewer is located – and historically it was the gentleman reviewer, not always – there are differences from America to Britain to Australia. The Americans are much more friendly as reviewers, will concentrate much more on the book rather than author so there are these differences that you have to learn to live with and if you look at the reviews every book has some reviewer saying this is the best thing Tom has ever produced and that same book will get somebody else saying this is garbage. You cannot win. But there are lessons to be learned if you look across the range of reviewing. Certainly the common thread is that he tends towards a melodramatic flourish at the end of his novels which sometimes needs to be brought under control, that the rapid rate of production does sometimes compromise the structuring of his work and so forth. The pacing sometimes comes in for criticism.

One of the early complaints was that he was too grim and too violent. Now if you’re writing about the convict era or you’re writing about the Second World War what else are you going to be? But again culturally there was a sense among many Australian reviewers at the time that one should really not hang one’s dirty linen out in public, that if you’re going to be an Australian novelist you should be a positive one, that you shouldn’t be so nihilistic, that Australia was this nice new country, we should all be looking to the sunshine and the future. So he did get a lot of flak for that.

He also got a lot of flak, deservedly, I think, for being an unreconstructed 1950s sexist and he admits this across his career and one of the things that you see happening across his career is an attempt to self-correct in terms of gender representation. One of the novels that indicates that was called The Woman of the Inner Sea where he talks about violence against woman and the survivor of a particular woman. Anyone read that one? There you go, proves my point. The Americans loved it but it didn’t do very well here, partly because again he was playing with certain Australian stereotypes which sold well in America but were pretty cliched for an Australian audience, I think. But he was also trying a certain postmodern experiment in that book where he addresses dear book-buyer and steps out of the story and takes this authorial persona. A lot of his editors had a great deal of trouble with that and a lot of the reviewers also just wanted a straight romance adventure as it were.

So again he never gives up on the kind of experimental side of literary writing while he is also trying to sell books to a wide range of people. That’s part of the nature of his career.

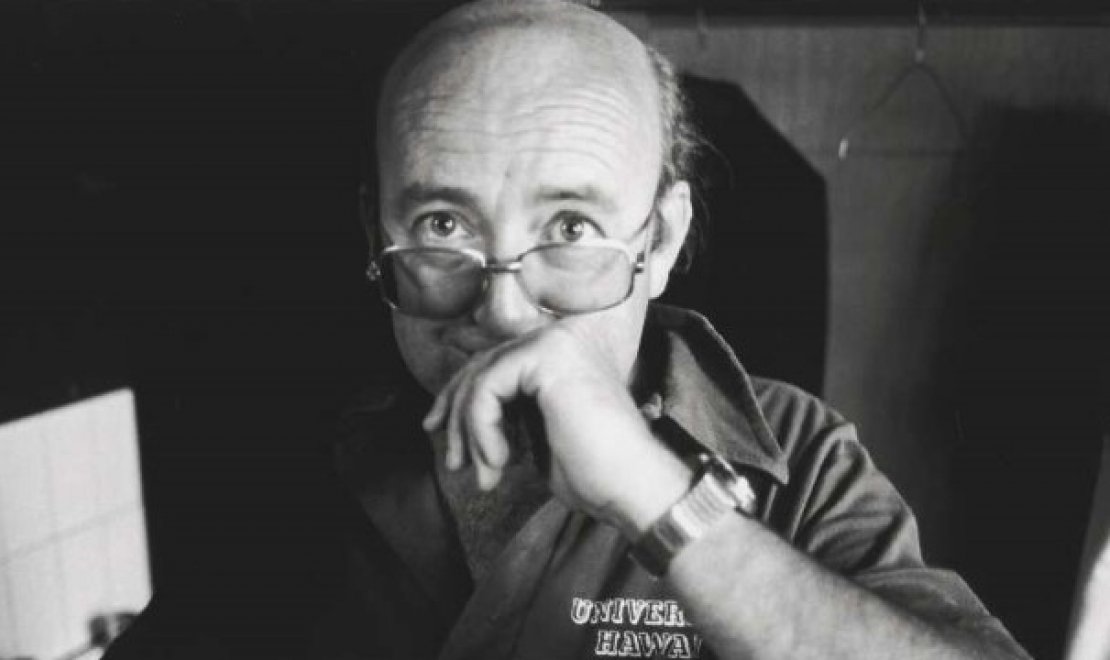

Questions about what is a literary career underpin the book or the thinking behind it. What are the assumptions of a proper literary career? Well here you can see him sideways as the cook acting in the film of The Chant of Jimmie Blacksmith. He also was an actor as a Catholic priest in an early film. I think it was one of Fred Schepisi’s very earliest productions. From an academic literary point of view this is an image of a sort of dilettante, somebody who is prepared to have fun, who’s not a serious figure whereas certainly in his early days he did inhabit the role of the serious literary figure. This is literally the writer in his garret except it’s the backyard in Ryde at the time and at the time also he had that bald, bespectacled nerdy sort of look which was appropriate for what we expected of a literary novelist.

Increasingly he repudiates this image, he repudiates the role he was given as the successor to Patrick White, probably partly ‘cause Patrick White was really rude about him, although he was rude about plenty of other people but as he read more and more of White he became more and more disenchanted with what he thought was a fairly overly artificed production, overly nihilist view of the world and resolved to be more cheerful, more demotic in his language, less tortured in his metaphors if you like than he was in his early writing in the hope also of selling more books. But in making that move and becoming – here we are, it’s the Sea Eagles, the Manly Warringah Sea Eagles Rugby League – in taking on this kind of populist image he also compromises to some extent the place we are prepared to assign him as a literary figure.

The question then comes how do we position somebody who becomes a public celebrity? Is that celebrity at the price of writing or does it sell more books? Are the two mutually supportive or mutually disjunctive? This I think becomes interesting when his books become filmed and I think there’s a very strong argument that The Chant of Jimmie Blacksmith, when it was filmed, worked for the book, preserved his role as a novelist, helped the novel to sell. It went into classrooms, of course, for at least one generation but when Schindler was filmed it became Spielberg’s Schindler and all the reviews thereafter talk about the film, they don’t talk about the novel or the novelist except to tell the story of how Tom got to tell the story that became the book of the film. So there’s this kind of double game in the literary career of how popular you can be and get away with it, especially in terms of film.

The other point I think about the nature of his career is despite the literary pretensions, which as I say he never gives up, it’s always been about the money. If you read the biography by Stephany Steggall of Tom she spends a lot of time going into the psychology of his early days, presenting him as an unusually tortured figure that is very much not the public genial leprechaun that he is often represented as these days in the press. But he was unable to complete his training for the priesthood, he went into a catatonic state and just had to leave. They wouldn’t give him a reference, they said oh no, the church doesn’t do that so he was on the street with no prospects.

I think that has underpinned his drive to keep producing, to keep earning to support the family and so forth right across his career. In a sense he says at one point that the more successful you get the faster you have to spin the wheel to stay running, that the costs mount up, that his work for Schindler’s Ark involved a hell of an amount of travel, a lot of reviewing, of interviewing of holocaust survivors, that the money he made from it which looks very, very handsome, he probably only banked about a quarter of that. He especially only banked a small proportion because he had agreed with some of the promoters behind the book that he would split the money and much of that money would go towards holocaust survivor support and so forth.

So he’s always been writing to earn an income. There’s an interesting link with the National Library in this case insofar as - the picture up there in fact is his first royalty cheque, still in shillings and pounds as you can see. Three pounds, 15 shillings and 11 pence but these were the days when – I think it was something like - £12,000 was an annual salary so it wasn’t too bad. But he kept very, very close tabs on his income and even when he moved it towards agents to look after he was still tracking how soon he could put out the next book in order to keep the bank balance afloat.

The National Library story comes in very early on when he’d sold some manuscripts of Jimmie Blacksmith and some editorial letters from Douglas Stewart who was at Angus and Robertson for $250 to the State Library of New South Wales, to the Mitchell. He then saw some letters from the National Library to other writers which had been offering about $1,000 for manuscripts so he went back to the Mitchell and said hang on a minute, I want more and they said oh no, we’ve already signed off on this, you can’t have any more. So he then gave his next batch to the Fryer Library which gave him a much more handsome amount of money.

Again as I say if you follow the paper trail by no means every book made a profit for the publisher so how does he keep publishers interested? Obviously once you win the Booker that helps. His name moves to the top of the cover of the book instead of at the bottom. He becomes an identity, the identity becomes bankable irrespective of what the book is from that point on but until that point at least the publishers weren’t necessarily making a lot of money out of him but he was managing to stay afloat because he was always working the next advance from sometimes another publisher. So he was staying afloat but staying afloat by floating nicely along the surface and pedalling frantically underneath and working across a whole range of activities like scriptwriting which could earn you a lot of money even if the film never happened as was his case many times, television writing, sometimes work for radio, certainly journalism and so forth.

Confessing to that commercial side of things again in terms of cultural politics, in terms of academic ideas of what a literary career should be put him very much in a commercial camp which was definitely not Bryce Courtenay if you look at the book reviews, if you look at sales, if you look at all sorts of attitudes to that. He’s very much positioned somewhere south of David Malouf, not too far south of Peter Carey but definitely north of Bryce Courtenay, Colleen McCullough etc, etc. So he’s in this interesting position of what we have now come to call a middlebrow writer which is a very flexible, indeterminate sort of place and he tends to fluctuate from one side to the other as he goes along, although increasingly he slides towards the populist commercial writer.

But within that sense of the career there are things we should remember. He produced this little book from Angus and Robertson, it’s called A Dutiful Daughter. Anyone read it? Yay, okay. For my money it’s the first magic realist novel ever published in Australia, probably an influence for David Ireland who went on to do other similar things. It’s a fantastical thing in which some of the characters become cows. Obviously you can see how Angus and Robertson again produced it as a literary book. It’s not huge, it’s got a nice dark, mysterious cover and what interestingly the text classics edition have done to this, they chose it because it was experimental to remarket it and the new cover is nice and bright and cheery and yellow. So how we read these books becomes part of how a career is constructed as well. This was very much a high art literary experiment at the time and now it seems to have become a much more popular thing because we all know what Salman Rushdie’s done and so forth, magic realism sells.

He also in 1980 produced this thing. Published by The Bulletin. It’s called The Cut Rate Kingdom. It’s a novel. It was a historical novel set during wartime, set in Canberra, in fact, and it’s full of Bulletin-type illustrations. What he was trying to do was produce something which academic publishing cannot produce and that was a cheap book at a time when prices in Australia were starting to go up and also to produce really an experiment in a kind of an illustrated novel. It’s a historical novel with historical illustrations in very much newsprint style. It was an experiment, it sold for $2.50 at the time. It was very much an experimental period in Australian publishing when you had a lot of literary magazines, small magazines, small presses starting to happen.

It didn’t go too well but it did sell a lot of copies, it sold enough copies for him to set up a scholarship, an award for some writers. But again in terms of how a career can work or not work for you Alan Lane took this up as a hardback but took it up years later after he’d won the Booker and of course by then nobody remembered that it had first come out in Australia and said oh this is rubbish, this is not anything like the greatness of Schindler’s Ark. Well, no. So this is kind of amnesia that often happens with a writer’s career which happens a couple of times in Tom’s case and gets in the way of a kind of a continuity of his presence in the market. So he has been a particularly interesting novelist even though we might think of him now as a kind of run of the mill populist.

I’ll start reducing my material because we are getting on with time, I’m supposed to be finishing about now. So I just thought I’d move quickly to some of the joys of working upstairs. This was at the time the collection of papers of Tom Keneally or at least part of the collection, there’s another number somewhere else. They’re all now offsite but I had the pleasure of working through this lot. More dust than you can think of. Probably be a few silverfishes crept in there as well but fascinating. All the manuscripts often again cut and pasted manually, bits of paper stuck on in the early days which then become computer text as you go along. It becomes harder to track.

I mean one of the things we’ll close with is just thinking about some of the problems of doing the research and I’ll come back to that but the other aspect of it is it is a huge mess, at least it was in that initial phase. Everything he ever collected was thrown in a box somewhere and you can see he’s got some cufflinks from his family history, there's a copy of the memorial plaque that’s outside the Opera House in Sydney, there are sporting tickets, there are tickets to the cricket, there’s the stuff from the Republican Movement and so forth. There’s his old school tie from St Patrick’s. So it’s all there as I said in largely an unsorted way and one of my moments of horror was when I came to finish the book and started doing the footnotes and discovered that a lot of this had been organised. So some of the boxes didn’t contain what I thought they once contained. So if you're happening to check the footnotes in my book be warned you’ll have to go back and doublecheck some of the boxes upstairs.

But some of the points of interest, the Catholic material. This is a shilling which was given to him by Archbishop Gilroy in 1942 when Gilroy was going around canvassing children as they were then for the priesthood and there are many other bits of Catholic paraphernalia through his archives. Here he is in his training for the priesthood role, robes. It was during that time that he indulged in a little bit of drama in fact, he directed a Shakespearean play because Shakespeare was the only thing allowed in literary form in seminary so that took him into drama later on.

One of the things that runs through his career, and again this is evidenced in a lot of the correspondence upstairs with his editors, is the drive to pseudonym. It’s not something we think about too much these days but he was constantly badgering his editors, saying I want this book to come out under a pseudonym. This is the name that he started writing under, Coyle is his mother’s name and initially it was a cover. He thought he’d shamed his family quite enough by bailing out from the priesthood, he didn’t want to shame them anymore by going public as a novelist and perhaps failing at that too, especially once some of the novels were exposing the Catholic Church in a rather shall we say humorous light. But this idea persisted through his career and one of the constant things was this book is a popular book, I want this to come out under a different name because my literary books should come under the Tom Keneally.

The publishers kept saying oh no, just keep doing the same thing. Well it's quite possible that he would have been more consistently successful had he managed to double brand himself. This book in fact is one of two that came out through [Carmen Carlisle] 46:15 and where was she at the time? I forget, one of the London publishers, because he had so many books on contract already with Hodder and Stoughton that he couldn’t squeeze another one in and at the time he had invested in a guest house in the Blue Mountains which was going rapidly broke so he needed cash. So he put this novel out and another one under the pseudonym and of course many scratchings of heads, particularly when the second novel said it was Tom Keneally on the back cover.

The second novel was what he claimed it was, namely a pot boiler that he was throwing out. This one wasn’t, this one he’d actually planned as part of his normal publishing series. It’s not a bad novel, in fact. As you can see it continues his very strong theme of war. He grew up during the war and was influenced by that and you can see from the artwork how it’s also carrying on some of his interest in religion with that cross formation there. One of the characters is a nun, the other character is an airman. So that idea of a double personality does continue through, coloured by the fact that he’s thinking of himself as performing for a double market.

Other joys from upstairs, this wonderful letter from Patrick White. As I say Patrick had been very rude about him. Tom finally put his tongue in his cheek and sent him a congratulatory letter when he won the Nobel Prize. Paddy responded with this card, Nobel Prize for Literature is more destructive for the writer than can happen to anyone so be warned, Yours, Patrick.

He wrote a book about Ethiopia, the war at the time for Eritrean independence called Towards Asmara which became an important political text in creating international consciousness about what was going on. It was in fact distributed by the Eritrean Government to overseas observers when they had their first elections to celebrate their independence. This is a card he got from Audrey Hepburn who was also an activist in the campaign at the time, thanking him for his work and for his novel.

Particularly when he became the Honorary Historian for Irish Australia if not Ireland, he wrote a huge book called The Great Shame which went to both Bill Clinton and Hillary. They both read it and this is a thanks from Bill for that novel. Hillary in fact featured in the celebratory film that was staged for his 50th year of publishing. So he was an extremely well connected person by the time he reached the latter stages of his career and it didn’t always reflect on his literary success but it is a success that has ranged across a whole range of genres, across a public platform and leaves open a number of areas of research which I think remain. His work for the stage I think has been underexamined. Susan Lever is in fact working on a book about his work with radio and television and other Australian writers. His role as a professional advocate in the Australian Society of Authors and the National Book Council and so forth I think could well be looked at. He worked on constitutional committees for the government and toured around Australia on some of those interviewing panels. I think there's still a literary book open for somebody who wants to write about his novels after the Booker. That’s it, thank you.

Applause

W: Thank you, Paul, that was fantastic, very thorough and as you can see the scope of the Tom Keneally collection here, it’s phenomenal. To have got through it, well, well done for getting through it for a start and it stresses the importance of libraries collecting whole archives even if unfortunately they do contain rugby tickets and stubs from one thing and another. I mean at some point somebody’s going to digest all this material and through finding aids and exploded finding aids and things nowadays people will be able to find it a lot better through Trove so that’s the good news.

End of recording