Try to imagine south-western Victoria, near present day Lake Condah, west of MacArthur, some 30,000 years ago. The Gunditjmara people living there experienced the development of a volcano and its associated lava flows as they spread across the landscape, filling river channels and blocking water flows. To them, it was the movement of the ancestral creator-being Budj Bim. In the process, extensive swamps and lakes were formed and these provided new opportunities for people to develop distinctly different lifestyles.

By 6,500 years ago, the Gunditjmara had developed these new landscapes into an amazing network of weirs, ponds, channels and connected waterways that supported their intensive kooyang (eel) farming. The adult short-finned eels (Anguilla australis), migrate down the rivers into the ocean and head across the Pacific Ocean to breed, including to the seas around Lord Howe Island (another World Heritage Area). Later the young elvers return to these same rivers and head upstream where they live and grow for many years before repeating the cycle.

Denisben, Lake Condah near Heywood. Remains of Aboriginal Stone Eel Traps, 2015, Flickr, reproduced under CC BY-ND 2.0.

The complex technology of the Gunditjmara network meant they could harvest enough eels not only for immediate consumption but also for smoking (which preserved them) and trade. Such intensive aquaculture enabled permanent settlement, and archaeologists have documented a settled society with villages of stone huts built from the basalt stones.

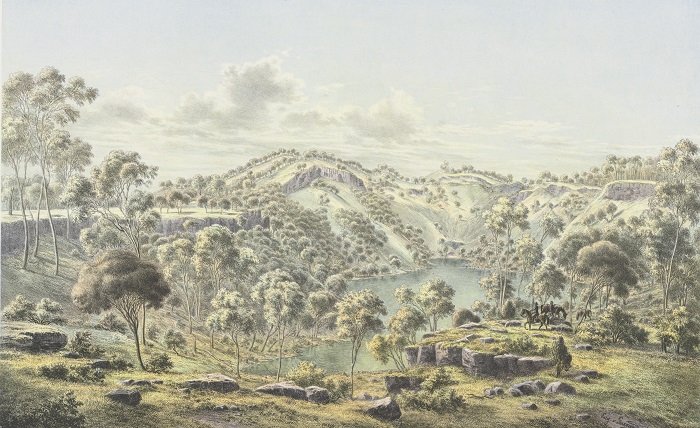

Not surprisingly, this astonishing site was inscribed as the Budj Bim Cultural Landscape World Heritage Area in 2019. The nomination followed Budj Bim’s previous inscription on the Australian National Heritage List, in a process led by the Gunditjmara community. The area is partly contained within the Budj Bim National Park. While originally called Mount Eccles, that name itself was a drafting error from Major Thomas Mitchell’s original Mount Eeles, and had no significance. The renaming by the Victorian Government, to celebrate the ancestral creator-being of the Gunditjmara, seems highly appropriate.

Eugen von Guérard, Crater of Mount Eccles, Victoria, 1867, nla.cat-vn583535.

Much as I would have loved to include a full chapter on Budj Bim in my book, World Heritage Sites of Australia, at the time of printing the World Heritage Committee had not met to consider the Budj Bim nomination. I had to be satisfied with a brief description as a potential future site. This issue does raise a question: how many more sites could we expect to see from Australia?

Before any site can become a World Heritage Area, it must be listed with the World Heritage Committee on what is called a tentative list for at least a year before it can be nominated for listing. At the moment, there are only two sites on Australia’s official tentative list, the Great Sandy Region in Queensland and some proposed extensions to the Gondwana Rainforests site.

But countries that are smaller than us, or that contain a much less diverse and significant natural heritage, have many more sites on their tentative list. For example, India has 38 sites inscribed (and 42 on its tentative list), Mexico has 35 sites listed (and 22 on its tentative list).

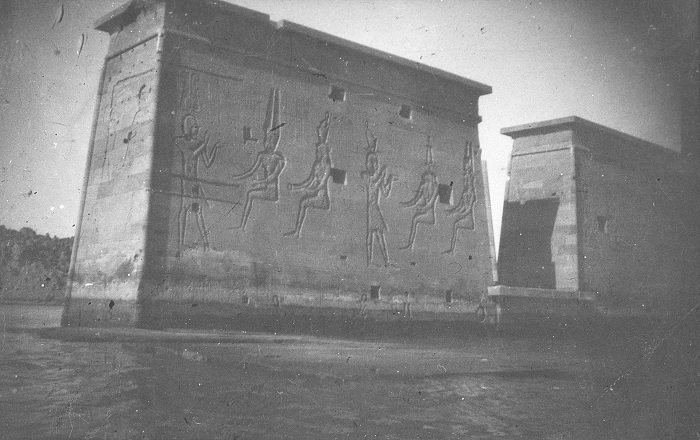

The Nubian Monuments from Abu Simbel to Philae were inscribed on the World Heritage List in 1979. Egypt has 33 sites on its tentative list.

Rex Nan Kivell, Temple of Isis, Partly Submerged Gate of Nectanebo in Aswan Dam on Philae Island, Egypt, before Relocation, Early Twentieth Century, between 1917 and 1919, nla.cat-vn3335190.

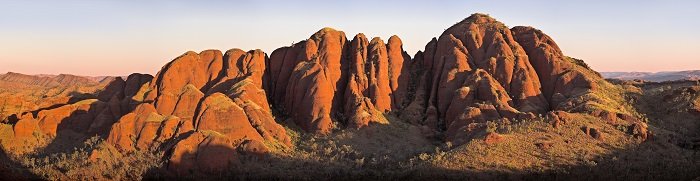

In the penultimate chapter of the book, I discuss potential future World Heritage sites in Australia, and draw attention to some clearly worthy places that could add at least another 20 sites. These include the floristic province of the south-west, the Kimberleys and the Burrup (Dampier) Peninsula in Western Australia; the Australian Alps across New South Wales, Victoria and the Australian Capital Territory; the Flinders Ranges and the Nullarbor Plain in South Australia; the Australian Antarctic Territory; and a number of potential desert sites across the nation. Many of these have already had much formal work done on their significance and simply await official nomination. Australia could easily have a tentative list of 20 sites.

Having spent 30 years working on World Heritage in Australia and overseas, the idea of writing a book about it seemed obvious. What was not so clear was the type and content of the book. Initially I had in mind a readership of colleagues, students, researchers and managers with a content that was fairly technical. On reflection, I was able to identify my most salient motive—I wanted more Australians to be aware of our outstanding heritage and to understand its significances on the global stage. I also envisaged an opportunity for everyone to celebrate the wonders of these exceptional places. The partnership with NLA Publishing was a perfect outcome that also gave me access to some amazing material.

Richard Elliot Green, Ragged Range, Kimberley, Western Australia, 2005, nla.cat-vn4831578.

When I started writing the book in 2017, Australia had 19 discrete sites inscribed on the World Heritage List, the first ones listed in 1981 (Kakadu, Great Barrier Reef and Willandra Lakes Region) and the most recent addition in 2010 (the Ningaloo Coast). In many cases, listing of these sites had eventually come about through community action, and sometimes involved conflict, so it was important to spell out the sometimes long and winding pathways to successful listing for each site. This let me recognise the roles of individuals and communities in achieving the long-term protection of these places—people such as Judith Wright, Myles Dunphy, Peter Hitchcock and John Sinclair to name just a few.

John Carnemolla, Lord Howe Island Aerial: The Most Southerly Coral Reef in the World.

Fortunately, and often despite conflict, things do change and sometimes for the better. Introduced species have had a severe impact on the native wildlife of the Lord Howe Island Group, but its board of management has carried out extensive pest eradication programs. A recent news report suggests that the rat eradication program seems to have worked, with extensive baiting apparently eliminating the mice and rats introduced to the island. If this is indeed successful, and it might require continuous monitoring for two years to be sure, then some of the threatened species can be re-introduced, including the astonishing Giant Phasmid that is the subject of a captive breeding program.

Despite the clear threats to some of our astonishing World Heritage sites, it is still the case that they capture some of the most exceptional natural and cultural heritage on the planet and continue to form the basis of significant visitation. My hope is that readers will become even better connected to these wonders and perhaps take steps to support ongoing protection and better management.

Peter Valentine is the author of World Heritage Sites of Australia (NLA Publishing, 2019) and a member of the IUCN World Commission on Protected Areas.