We all know that we inherit the colour of our eyes from our parents.

If you sneeze when you look at the sun, that too is passed down through your genes. So is your ability to curl your tongue and when you are likely to notice that first grey hair.

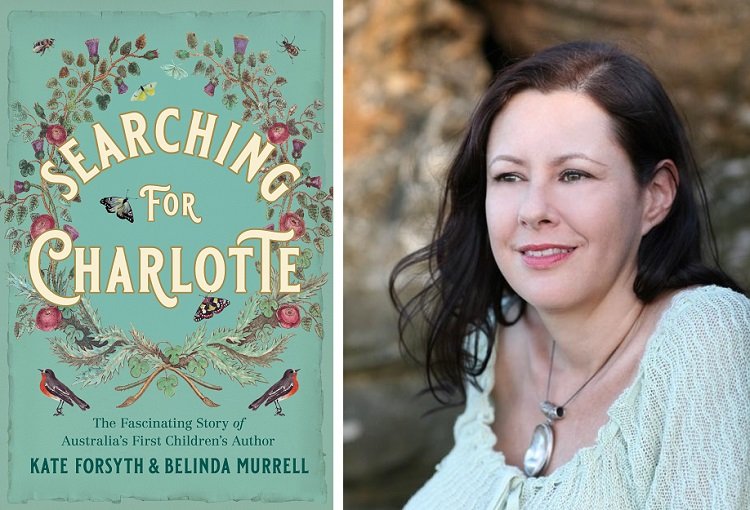

Dr Kate Forsyth and her new book, Searching for Charlotte, written with her sister Belinda Murrell.

One thing I have always wondered is whether my lifelong compulsion to write was encoded in my DNA. People often ask me, ‘when did you first decide you wanted to become an author?’

I always answer, ‘I was born wanting it’.

My sister Belinda Murrell is an author too. So is my brother. The three of us have published more than 90 books between us.

We are not the only writers in our family. There are poets, novelists, journalists and biographers going back generations. My sister and I have just spent the past 2 years researching and writing Searching for Charlotte, a biography of our great-great-great-great-grandmother, Charlotte Waring Atkinson, who in 1841 wrote the first children’s book published in Australia.

Her youngest daughter, Louisa Atkinson, was the first Australian-born female novelist. Other writers in the family include Robert Waring, a friend of Ben Johnson, who wrote Effigies Amoris in English, or the Picture of Love Unveil’d in the mid-1600s; Anna Letitia Waring, 19th-century poet and composer of hymns; and her father the Reverend Elijah Waring, who wrote Edward Williams: The Bard of Glamorgan in 1850.

Charlotte Waring Atkinson, Flowers, 1843, courtesy Neil McCormack.

Writing does seem to be in our blood.

There are, of course, many other families in whose veins ink seems to run. The Brontë sisters. The Grimm brothers. The Rossetti siblings. Mary Wollstonecraft and Mary Shelley. Alexandre Dumas, père, and Alexandre Dumas, fils. Four generations of Waughs. The Sitwells. Kingsley Amis and his son Martin. A.S. Byatt and Margaret Drabble. Stephen King and his son Joe Hill.

Literary DNA seems to be remarkably potent.

So is there a writing gene?

The inheritability of creativity has always been difficult to study, simply because creativity is so difficult to define and measure. What is genius? What is artistic talent? Is the compulsion to create enough, or must the work have some kind of worth? How does one measure that worth?

Some writers are enormously celebrated in their time, only to be forgotten a few generations later. Others find fame only after their deaths. Some write only one book, others dozens. Some are both loved and loathed, according to the taste of their readers.

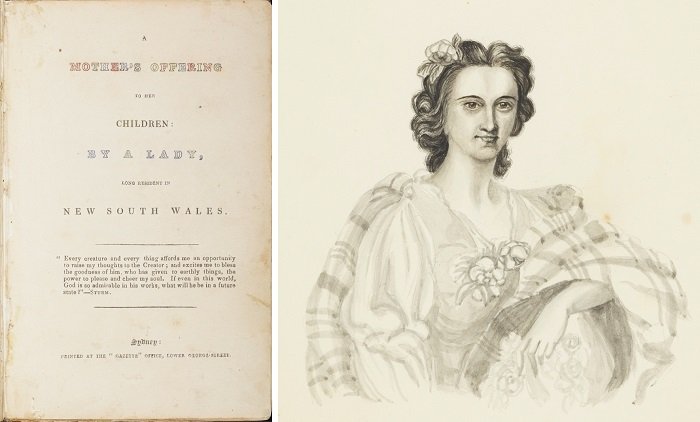

Our great-great-great-great-grandmother Charlotte Waring Atkinson falls into the ‘unjustly forgotten’ basket. Her book, A Mother’s Offering to Her Children, was published anonymously, ‘By a Lady Long Resident in New South Wales’. It was positively reviewed upon its publication, but now there are only a handful of first editions remaining, including one precious copy in the National Library of Australia. Her extraordinary life and achievements are hardly known beyond scholarly circles.

Left: Title page of A Mother's Offering to Her Children by Charlotte Waring Atkinson, 1841, nla.cat-vn777812; Right: Charlotte Waring Atkinson, Self-portrait, from the Jane Emily Atkinson Album of Watercolours and Drawings, 1843, courtesy State Library of New South Wales.

Yet her book was the first children’s book with an Australian setting, the first to draw upon Australian colonial history, the first to describe the lives of the Australia’s First Nations people. She also wrote poems and stories, was a fine visual artist and a proto-feminist who fought for her right to live a self-determined life.

The fact that her daughter Louisa Atkinson was also a celebrated artist and author supports the idea that their creativity was passed down from mother to daughter. However, Charlotte also raised her and taught her all she knew.

It’s the age-old nature versus nurture argument.

Recent studies into the inheritability of creative writing seem to show that it is indeed a trait that is passed down through the family. The most striking was led by Anna Vinkhuyzen, now a research fellow at the Institute for Molecular Bioscience within the University of Queensland. She and her team drew on data from the Netherlands Twin Register, which contains information on 1,800 identical twins and 1,600 non-identical twins. They found high levels of heritability (83%) for creative writing, which is much higher than for a broader category of arts such as painting (56%).

Other approaches have come up with similar results, showing that DNA does indeed play a strong role in creative writing. However, as Siddharta Mukherjee writes in The Gene: An Intimate History, ‘it is nonsense to speak about “nature” or “nurture” in absolutes or abstracts ... the development of a feature or function depends, acutely, on the individual feature and the context.’

In other words, creativity is a constellation of fiery sparks ignited in a multitude of ways. The willingness to play, long hours of practice, dedication to one’s art, the desire and drive to create – all these matter too.

Nonetheless, it gives me great joy to know I am connected by a golden chain of DNA to my long-ago ancestor, who loved words and writing as much as I do.

Dr Kate Forsyth is a bestselling novelist, poet and essayist. Searching for Charlotte (NLA Publishing, 2020) has been longlisted for the 2021 Indie Book Awards and is available now through the National Library Bookshop and selected retailers.