The early twentieth century was a golden period for Australian literature. This was particularly true of female novelists, who rose to prominence in the late 1920s. They arguably produced the best work, from this period through to the end of the Second World War. Yet some of the finest female writers encountered gendered attitudes, wrote under male pseudonyms, struggled to get their work published in Australia and received belated recognition. A closer look at three eminent early twentieth-century novelists—Henry Handel Richardson, Miles Franklin and Christina Stead—reveals that each faced significant obstacles in writing and publishing their work, much of which is now celebrated as leading examples of Australian literature.

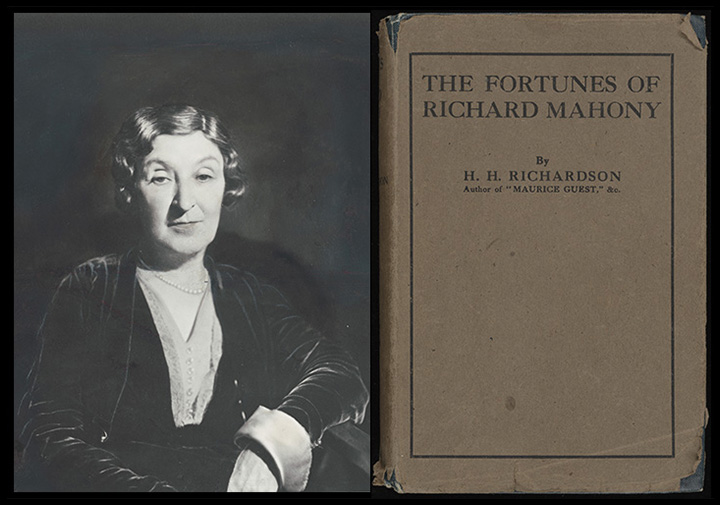

Left: Portrait of Henry Handel Richardson, 1930s, nla.cat-vn1592787; Right: Henry Handel Richardson, The Fortunes of Richard Mahony, 1917, nla.cat-vn2056232

Henry Handel Richardson (Ethel Florence Lindesay Robertson nee Richardson, 1870–1946), the oldest of the three, is one of Australia’s most acclaimed novelists. She is best known for her coming of age classic The Getting of Wisdom(1910) and the historical fiction trilogy The Fortunes of Richard Mahony (1930). Having moved overseas to study music in 1888 and spending most of her life in England, Richardson made only one return visit to her homeland in 1912 to research her trilogy. Some of the notes from this trip are held in the Library’s collection of her papers.

Like some other female writers of the era, Richardson wrote under a male pen name. Hers was part truth and part fiction, with the spurious names ‘Henry Handel’ added to her maiden surname. One of the reasons she adopted a male pseudonym was to enhance critical reception of her work, as she explained in 1940:

There had been much talk in the press of that day about the ease with which a woman's work could be distinguished from a man's; and I wanted to try out the truth of the assertion.

Her identity - including her gender - remained a secret for many years.

The blend of fact and fiction of her pen name is echoed in the plots of her novels. She drew on family circumstances when writing works such as The Fortunes of Richard Mahony. The series commences during the Victorian gold rush and chronicles the life of restless doctor Richard Mahony (modelled on Richardson’s father), who, during periods of boom and bust, moves his family to various towns in Victoria and ‘home’ to England. His tragic financial, mental and physical decline and the impact on his family are powerfully written. Richardson took pains to stress that her books should not be considered autobiographical, despite being loosely based on family and historical events.

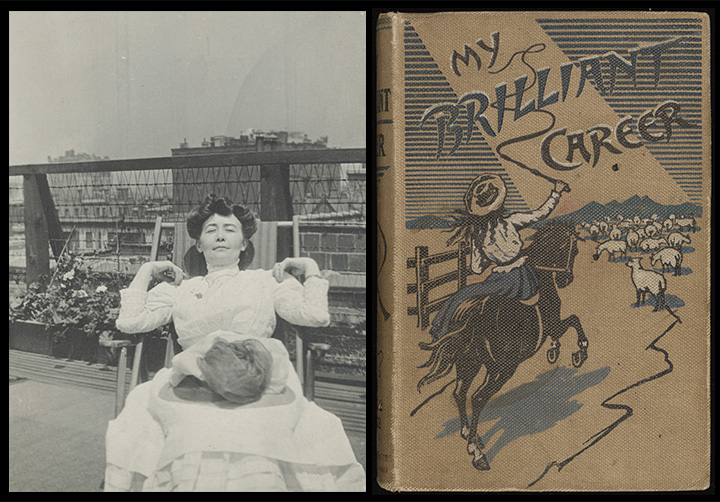

Left: Stella Miles Franklin, 1900s, nla.cat-vn2463484; Right: Miles Franklin, My Brilliant Career, 1901, nla.cat-vn1666224

Like Richardson, Miles Franklin (Stella Maria Sarah Miles Franklin, 1879–1954) also chose against writing under her real name. Miles, her masculine-sounding middle name, was a comfortable nom de plume that enabled her to disguise her gender and increase her chances of being published. She completed her first novel, the feminist classic My Brilliant Career (1901), when she was 19. Rejected for publication in Australia, it found a supporter in the United Kingdom in bush poet Henry Lawson. In response to Franklin’s request for aid, he took the book with him to London. There, his literary agent J.B. Pinker secured William Blackwood and Sons of Edinburgh to publish it.

My Brilliant Career was met with immediate critical acclaim. However, few realised the intended irony in the title, which was slightly altered by its publishers; the question mark in the original - My Brilliant (?) Career - adds a degree of uncertainty to protagonist Sybylla Melvyn’s decision to reject a marriage proposal in favour of pursuing a career as a writer. When writing to Pinker, Franklin insisted that the question mark be included in the title, and also asked him to:

on no account allow ‘Miss’ to prefix my name on the title page as I do not wish it to be known that I’m a young girl but desire to pose as a bald-headed seer of the sterner sex.

When her identity as the author became apparent, the novel was also assumed to be autobiographical. In an era where traditional gender roles were upheld, particularly in rural areas where she was raised, this assumption embarrassed Franklin and her family.

Franklin continued to write novels that drew on her experiences growing up on the Monaro plains, even while living in America and England between 1906 and 1932. These were published under various male pseudonyms - mostly notably Brent of Bin Bin - to avoid comparisons with her debut work. Of the pseudonyms under which she wrote, she is generally remembered as Miles Franklin. Her name has taken on new significance through the Miles Franklin Award for Australian Literature, which was established through her bequest in 1957. In 2013, an award celebrating Australian women’s writing, the Stella Prize, was named in her honour.

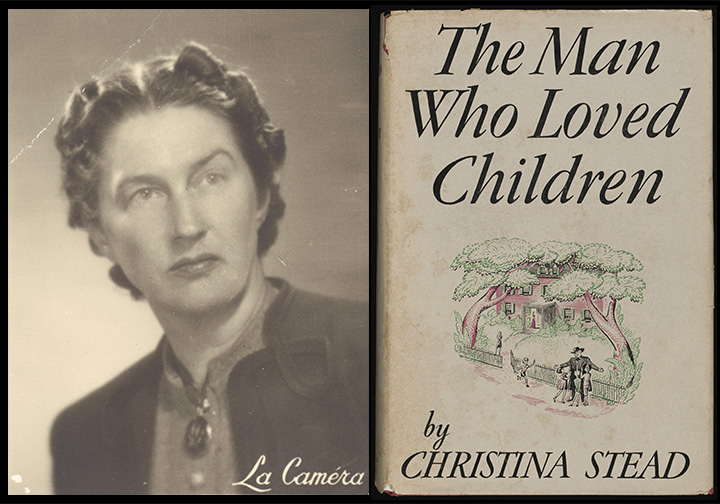

A generation younger, Christina Stead (1902–1983) was not compelled to write under a male pseudonym in order to get her work published. She did, however, experience setbacks to her literary career, particularly in Australia. Today, Stead is considered one of the country’s most important writers who also boasts an international reputation. Living in Europe and America between 1928 and 1974, Stead published the first of her 12 novels, Seven Poor Men of Sydney, in 1934.

Left: Christina Stead, c.1938, nla.cat-vn4579758; Right: Christina Stead, The Man Who Loved Children, 1940, nla.cat-vn1711006

Whereas Richardson was able to develop a strong literary reputation in Australia despite living overseas, the same was not true for Stead. Letters held at the Library reveal her frustration at constant rejection from local publishers. As the books were published overseas, they were more expensive than locally produced works, further inhibiting her profile in her country of birth. In 1939, while writing her masterpiece The Man Who Loved Children (1940), she wrote to her cousin and explained that ‘I should like to publish my next novel in Australia’. It drew on her childhood experiences in a large blended family overseen by a domineering father. Ironically, not only was the novel rejected in Australia, but her American publisher, Simon & Schuster, insisted that the setting be changed from Sydney to Washington in order to broaden its appeal to Americans.

Stead was largely overlooked in Australia during her lifetime. It was not until the 1965 reissue of The Man Who Loved Children that she began to receive recognition as a literary giant in her homeland. When she returned permanently to Australia in 1974, she was awarded the inaugural Patrick White Award for established yet underappreciated writers.

Female novelists wrote some of the finest Australian literary works of the early twentieth century. Today, Henry Handel Richardson, Miles Franklin and Christina Stead are considered among the country’s greatest writers. During their lifetimes, their literary careers were impeded by a number of factors—many related to gender stereotypes. Through their perseverance, they left a rich legacy that continues to inform the literary landscape.

Grace Blakeley-Carroll is a curator within the Library’s Exhibitions Branch.

This article was originally published in the September 2017 edition of the Library's Unbound magazine.