I couldn’t have been further away from the water: sitting at a desk in the National Library of Australia Reading Room, my lap-top was humming and I was madly taking photos and writing notes. It was hardly a Saturday evening casting squid jigs off the rocks. And yet this desk job had a decidedly fishy feel.

Trolleys teetering with fishing magazines are wheeled up beside me, along with various ephemera from the archive, like old tackle and tourism advertisements, fishing guides from the nineteenth century, and fisheries reports that angst over the state of fish stocks in Sydney Harbour in the late 1800s.

I was researching a history of fishing in Australia, which went on to become an illustrated book, The Catch: The Story of Fishing in Australia, published by NLA Publishing, and is now an exhibition of the same title on display in the National Library of Australia’s Treasures Gallery. As I waded through page after page of fishing accounts, I was struck by how they communicated the same feelings of natural wonder and excitement for fishing I experience today.

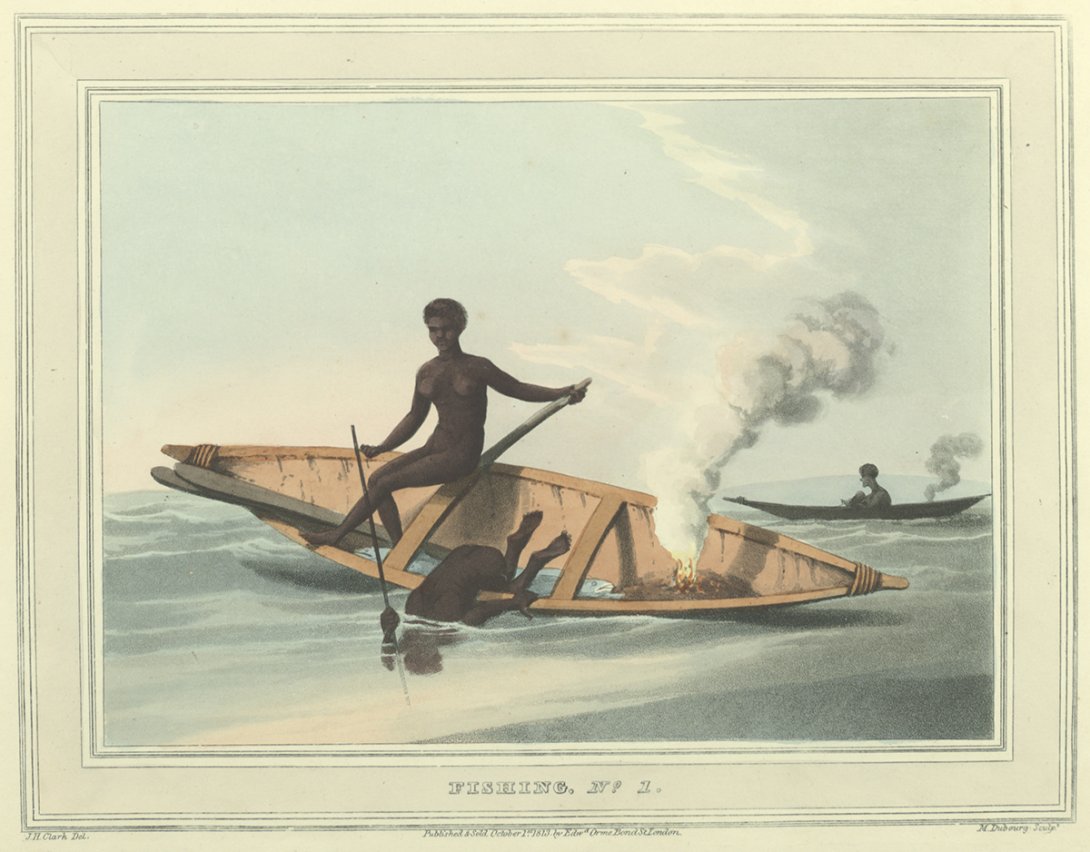

John Heaviside Clark, Fishing No. 1, Plate in Field sports &c. &c. of the Native Inhabitants of New South Walesby John Heaviside Clark (London: Edward Orme, 1813), nla.cat-vn2259601

Anthropological and colonial documents stretched into deep time and revealed extraordinary Indigenous knowledges, as well as the natural bounty of Australia’s fisheries before mass urbanisation and industrialisation.

Some of those sources can only be found deep in the pages of texts not associated with fishing, such as William Wills’ journal of his ill-fated cross continental exploration, where he described intricate fish traps in central Australia.

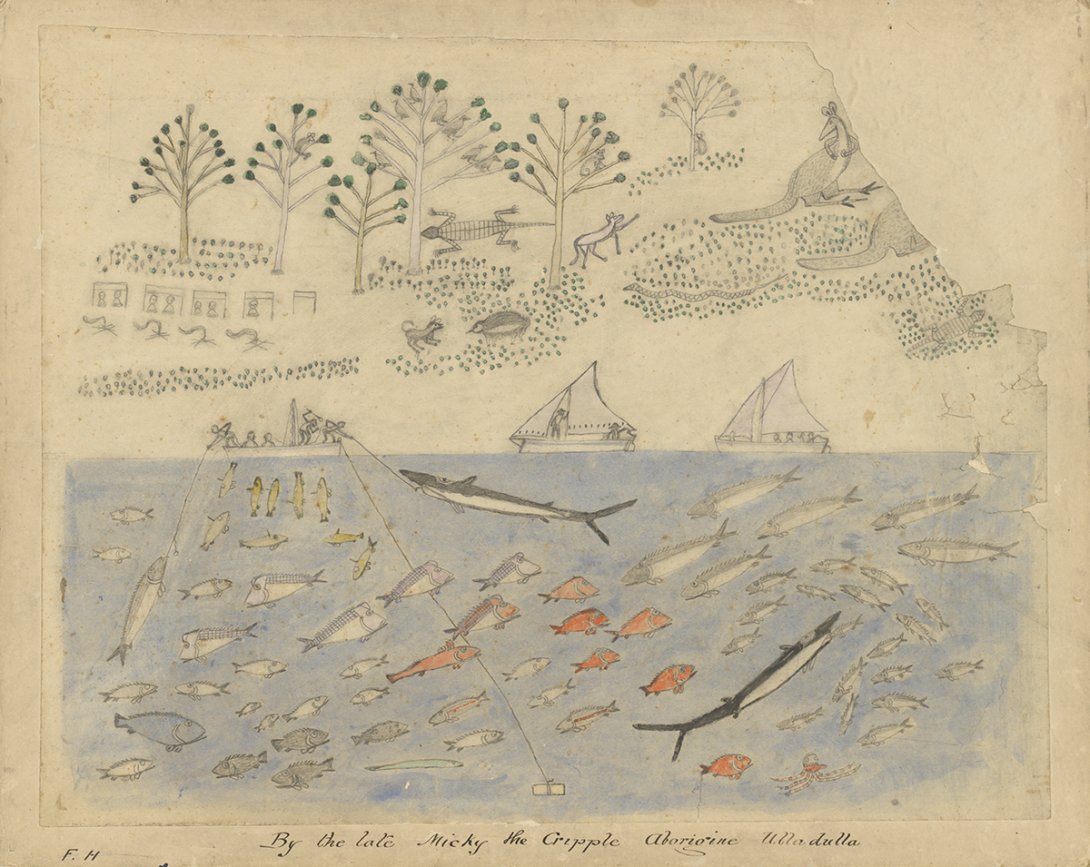

Others, like the digitised works of colonial artist Joseph Lycett, John Heaviside Clark or Indigenous artist Mickey of Ulladulla, bring together invaluable readings of Indigenous practices over time.

Micky of Ulladulla, Fishing Activities of Aboriginal Australian People and Settlers near Ulladulla, New South Wales, c.1885, nla.cat-vn906861

Anthropological and archeological works, such as RH Matthews’ study of the Brewarrina fisheries, described the remnants of vast, curving fish traps made from river stones that lie there still. In the early spring, or during a large flow of fresh water after heavy rains, enormous numbers of fish would travel up river, swelling the eddies and currents with a mass of writhing tails and fins. Aboriginal fishers—men and women from the Ngemba, Wonkamurra, Wailwan and Gomolaroi nations—kept watch from grassy embankments above the river and as soon as enough fish had entered the labyrinth of traps, they rolled large rocks across the openings, ensnaring them for a seasonal fishy feast.

It’s hard not to be moved by these windows into the past. The fact that we share these places and fishing practices still—that we can see those rock ledges, river bends and bommies, has been one of the unexpected treats I’ve taken from writing this book.

Dennis Brabazon, A Ninety-Seven Pound Murray Cod, Caught by a Professional Fisherman near Collendina Station in the Corowa District, New South Wales, 1924, nla.cat-vn5042530

The other is a sense of Australia’s environmental fragility. The Murray Cod fishery has closed, along with commercial Southern Bluefin Tuna, and recreational pressures on snapper fisheries are also reducing seasons and catches. Even now, after decades of fisheries management, there are few places in Australia where we canreally seewhat a river full of Murray Cod or a reef brimming with snapper actually looks like.

The Catch isn’t just a history of catching fish, but an exhibition that points to some of the tensions between our love of fishing and its effects on our environment, the ways Indigenous communities used fishing to adapt to life following colonisation, the ways families and communities formed (and divided) around fishing nets and small harbours, as well as the many questions yet to be answered about how we can manage our fisheries into the future.

Dr Anna Clark is an Australian Research Council Future Fellow and Co-Director of the Australian Centre for Public History at the University of Technology Sydney. The Catch: The Story of Fishing in Australia, her seventh book, is a perfect marriage between her love of fish and fishing and her passion for Australian history.