Dr Judith Nangala Crispin is a poet and visual artist with a background in music. Much of Judith’s writing is centred around the experience of searching for her Bpangerang ancestry, and her long-term friendship with Warlpiri people.

As part of her National Library of Australia Creative Arts Fellowship for Australian Writing, Judith is writing a book of prose poetry and drawings around the life of Charlotte Clark, a Bpangerage custodian of goanna songlines, and Judith’s matrilineal ancestor. Charlotte only exists in orally transmitted anecdotes, entries in a ledger, and a single photograph - but her world was captured in drawings by her countryman Tommy McRae, held by the National Library.

Judith will present and discuss her research on Wednesday 3 June at the National Library of Australia.

My family tree has missing branches...

People with missing birth certificates; branches of the family we were discouraged from contacting because they were unreliable. Those of my great-grandmother’s generation with a narrative about our ancestry were dismissed as compulsive liars.

We were told that our olive complexion came from Spanish seafarers – all these outlandish stories, and we believed most of them. And then it just became gradually clear that it wasn’t true. My uncle tracked our family line to an Aboriginal woman in the Wangaratta region, but died before he found anything conclusive. So I started looking for these missing ancestors. We tracked them to Bpangerqang Country.

Trying to actually find that connection took almost 20 years. It was almost impossible because, until recent times, the way white records were created and maintained was designed to erase Aboriginal history. If you were even up to a quarter-Aboriginal before 1960, chances are you don’t even have a birth certificate. If you did, it probably has the surname listed as the name of the house that you were living in. Then when you’ve got a family history full of different made-up stories as well, it becomes really tough.

After 20 years, it wasn’t even me who found the parallel branches of my family – they found me. Uncle Freddy Dowling, who’s a descendent of Tommy McRae and also of Charlotte Clark, found me and emailed me to say ‘we’ve been looking for you lot’. Many of the old people keep generations and generations of lineage in their memory. Those of our ancestors who were issued no birth certificates still existed; they still had children. If we rely on the white record alone we will see only what the authorities of a previous time wished us to see.

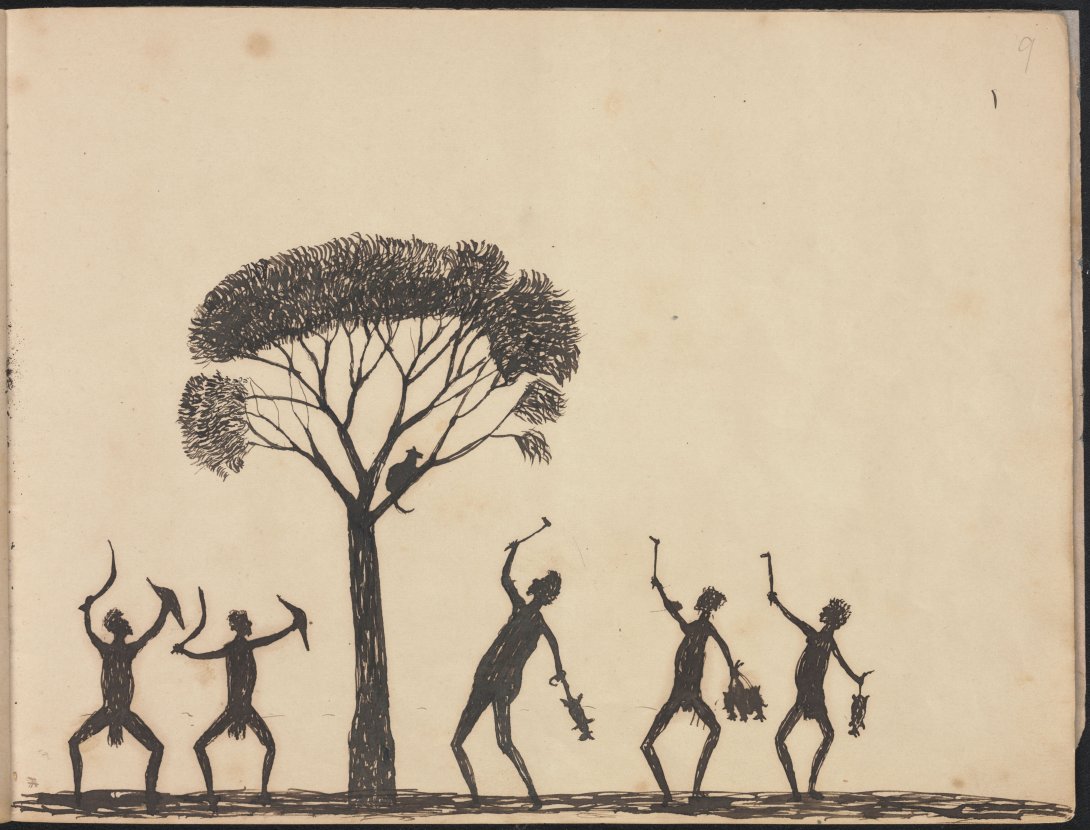

Possum sitting in the branch of a tree, Wahgunyah Region, Victoria, 1880, Tommy McRae (nla.obj-139419447)

Charlotte Clark is a kind of symbol for me, in a way...

Imagine if you found out about someone in your family history of whom the rest of the family was so ashamed that they literally erased them from the record. I’m in the fortunate position where I can say, publicly, that I’m interested in Charlotte, and I’d like her to be acknowledged. Nobody in previous generations was in this position, because the cost of acknowledging an Aboriginal ancestor would have been too great.

For me, Charlotte is a link to something really vital and important; a link to the ground that we stand on, to 65,000 years of a continuous connection with the land.

I’m not creating an imaginary biography and saying “this is the truth.” The truth has been erased and I can’t get it back. I’ll never have absolute certainty about Charlotte, so this book will be the history that I want for her. This is how I see her when I imagine her.

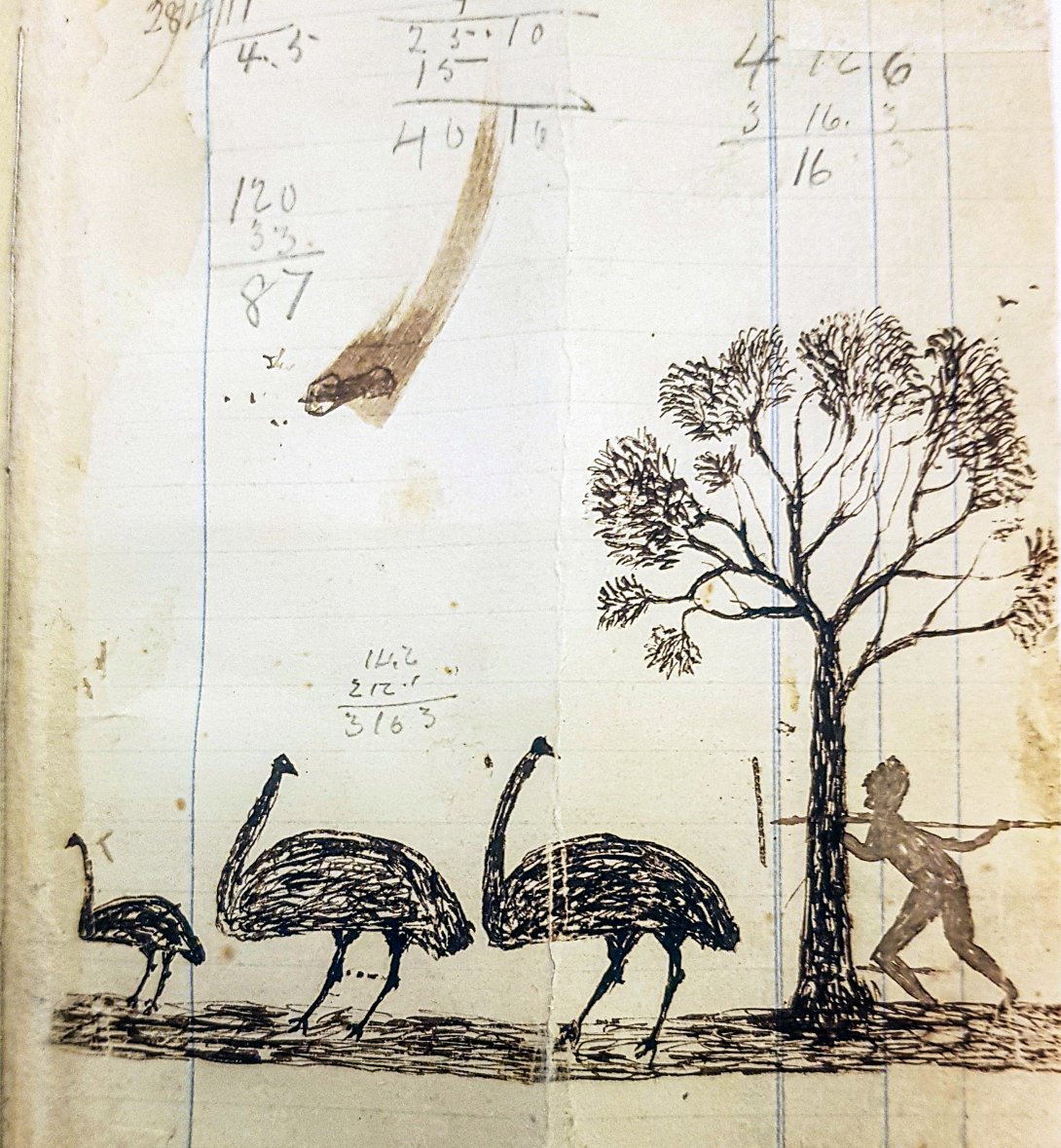

This sketchbook was in the Treasures Gallery at the National Library under lock and key...

We know when Charlotte died, when she was born, we know what region she was living in – so we know roughly where she spent her life and when. And these drawings were made by Tommy McRae in that area, at that time.

Tommy McRae was an Aboriginal man living in north-eastern Victoria and the New South Wales Riverina – essentially the Murray River.

He would have been incredibly important among his own people, and among the predominant powerholders of society he was treated like this kind of novelty, but his dignity and grace come through in his work.

This sketchbook was on temporary display in the Treasures Gallery at the National Library under lock and key. Looking at the drawings, I can get a sense, through the black gaze, of what the Murray River region was like a that time.

They’re from a time in our history when there were atrocious massacres taking place in Victoria. People were being displaced, and the situation for Aboriginal Australia looked pretty dire. But these drawings are so full of light, there’s no anger, there’s no bitterness. They show something about the dignity of those people at that time, and that really informed the way that I was writing. In any story where bad things have happened there’s always different ways to look at it. I want to pick the way that has the most light in it.

Hunting emus, Wahgunyah Region, Victoria, 1880, Tommy McRae (nla.obj-139418547)

I want to show people that there’s a pathway out of this mess...

The Australian Institute of Aboiriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies said a few years ago that if your family has been in this country for 7 generations, the chances of you having an Indigenous ancestor are overwhelming. There are so many families out there who have an Indigenous ancestor and they either don't know, or they do know and they don't know how to start looking, or they've been looking and they've found nothing. I want to show people that there's a pathway out of this mess.

A Warlpiri friend said to me ‘You don’t have to be defined by your ancestors’. You don’t have to become an extension of that lie, you can decide that it changes with you. I could have passed on a sense of shame – shame that our family had lied about our ancestry, or shame that we still can’t speak with any certainty about our ancestry.

I could have given this to my daughters and my grandson, but I don’t want to do that. I want to leave them a sense of privilege, that we stand legitimately in this land – that we can form our own unique relationship with the land, our own relationship with family, and our own relationship with the past – even if pieces of that past are vague or missing, we can carry that as a blessing and not a loss.