‘Before you fairly start this story I should like to give you just a word of warning... Not one of the seven is really good, for the very excellent reason that Australian children never are.’

I find it hard to read these lines from the opening of Seven Little Australians without laughing. Author Ethel Turner (1870–1958) cautions her readers that there is something particular about Australian children. Perhaps it is because she celebrated Australian children's ‘unique’ qualities this classic children’s novel has resonated with readers since its publication in 1894.

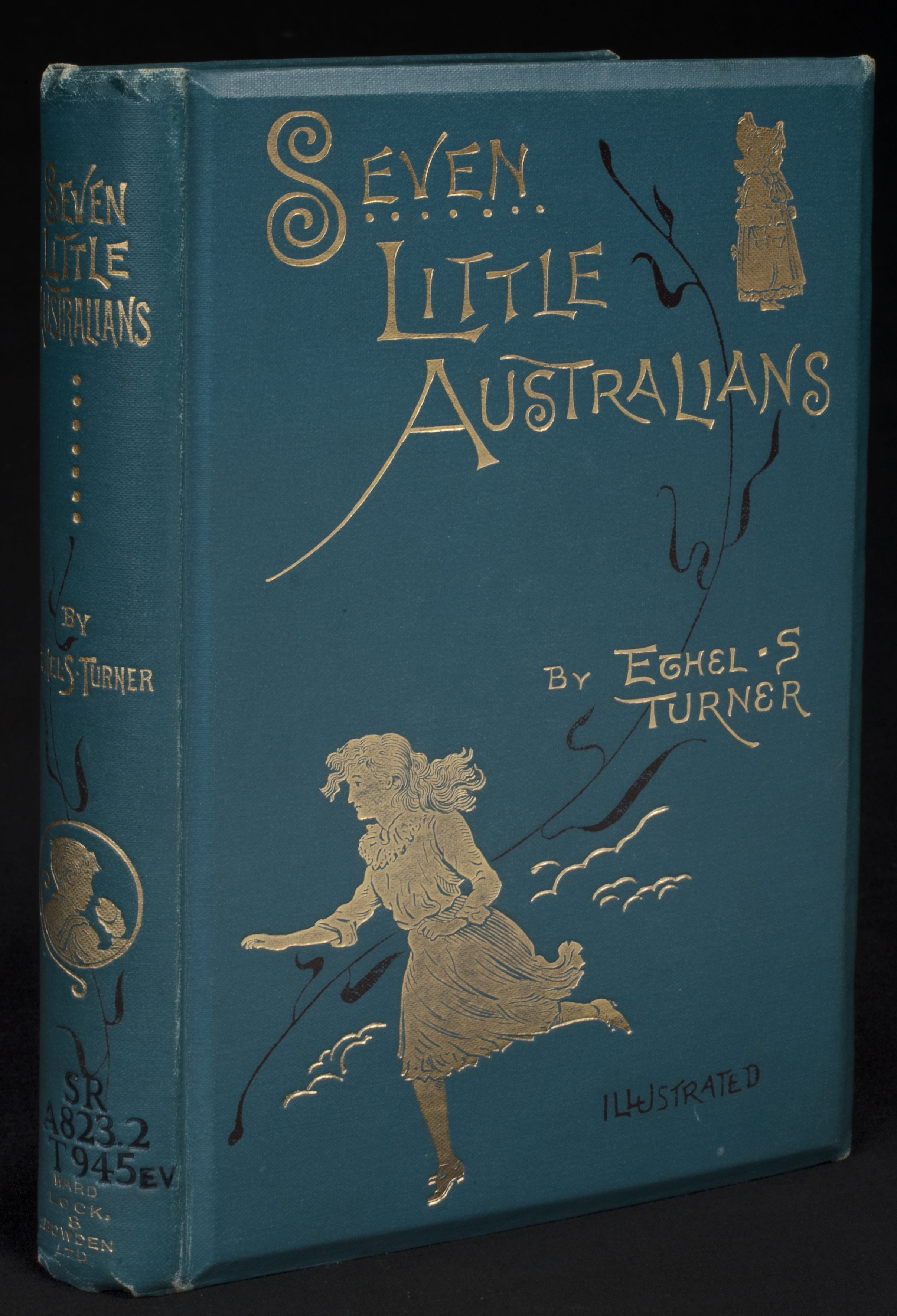

Ethel Turner (1870–1958), Seven Little Australians, London; Melbourne: Ward, Lock and Bowden, 1894. Australian Printed Collection, nla.cat-vn2539508

Set primarily in Sydney in the 1880s, Turner’s debut novel tells the story of the Woolcot children - Meg (16), Pip (14), Judy (13), Nell (10), Bunty (6), Baby (4) and infant ‘The General’ - each of whom possesses a strong and different character. They live at Misrule with their father, Captain Woolcot, and stepmother, Esther (the biological mother of the youngest). The book recounts the children's many adventures and mischievous antics. It's instant success made Turner a household name.

I first read Seven Little Australians as a child in the 1990s. What I loved most about it was learning about the past. The children’s lives seemed so foreign to me and the book offered a window into the colonial period. When I revisited the book, while working on the Library’s exhibition Story Time: Australian Children’s Literature, I found myself once more engrossed in the lives of the Woolcot family. This time I was more aware the book’s themes, such as coming of age and familial love. Part of the story's enduring appeal of the story lies in the way it explores the complexities of family life and the fun and sorrows of childhood.

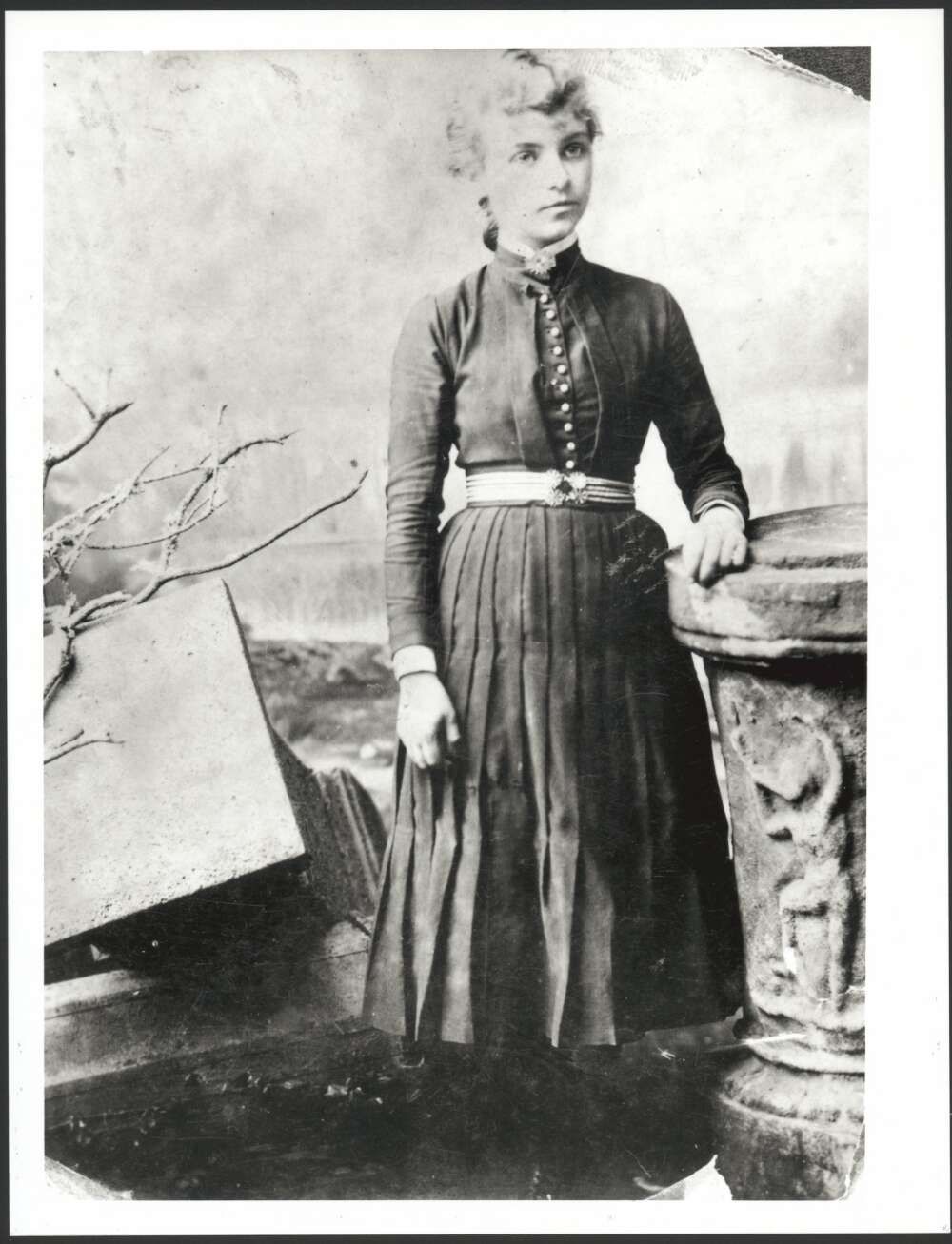

Ethel Turner at Girls High School Sydney about 15, 1885, photograph, Pictures Collection, nla.cat-vn2246607

Rereading Seven Little Australians and looking through Turner’s papers piqued my interest in the author’s life. Ethel Burwell was born England in 1870. She lost both her father and stepfather at an early age and migrated to Australia with her mother and sister. Here her family expanded with her mother’s third marriage and the arrival of another sibling. Her experiences no doubt informed the plot of her most famous book. Turner was a prolific writer—completing more than forty books—but is primarily known for Seven Little Australians.

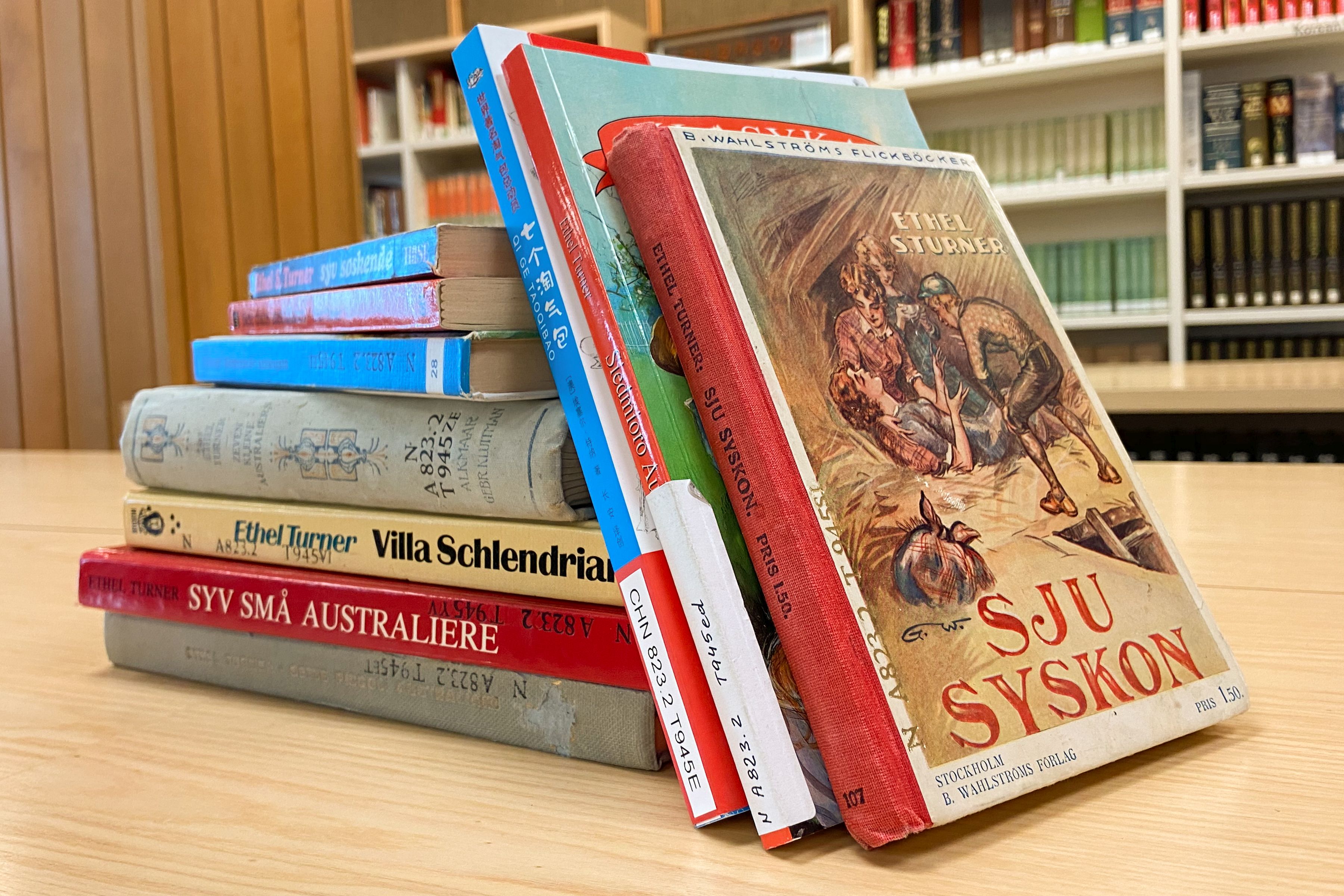

When Seven Little Australians first hit the shelves, few would have imagined that it would remain in print for over a century and be adapted for stage and screen. The book has been translated into numerous languages, read by millions of people and reprinted more than 50 times. It has been in print longer than any other Australian children’s book. I enjoyed calling up the dozens of editions and translations of the book, held at the Library (including a braille version). The covers of these books revealed how each adaptation and translation reflected the period and culture in which it was published. Among my favourites is the first edition, a hardcover edition embossed with gold letters. I was also drawn to a 1970s Japanese version, which has a classic 70s colour palette.

A selection of translations of Seven Little Australians from the National Library of Australia's collections

The Library’s Turner holdings also include manuscript notes from Seven Little Australians and other papers. In a draft chapter, Turner writes about life at Misrule. While not included in the published book, this scene offers insight into the development of the story. One of the most interesting items is a draft article in which she playfully lists the various reasons why she wrote Seven Little Australians, such as: ‘Because I had read that Little Lord Fauntleroy had made £20,000 for its writer & I had plenty of uses for £20,000’. It tells us a lot more than the brief entry in her diary on her twenty-third birthday: ‘Seven L. Aust.—sketched it out’.

Today, 150 years since Ethel Turner’s birth, her classic book occupies a unique position in the history of Australian children’s literature. Rereading it as an adult reminded me of the special place the story holds in my heart. Perhaps it is because the family still seems so real and relatable—and because the story does not have a typical happy ending—that it has stood the test of time.