There is no denying that Mavis Robertson lived a fascinating life. In fact, according to Dr Alice Garner, ‘her experiences in the Communist Party, the peace movement, early women’s liberation, documentary making and later in the development of industry and compulsory superannuation, offered a very interesting pathway into understanding some significant moments in Australian history’.

For her 2023 National Library Fellowship, Alice set out to produce an audio documentary series using the Library’s collections that fully explored the sounds of this extraordinary life.

Bronwyn Ryan: Thank you for attending this event, coming to you from Ngunnawal and Ngambri Country. I'd like to begin by acknowledging Australia's First Nations peoples as the traditional owners and custodians of this land, and give my respect to the elders past and present, and through them to all Australian Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples.

This afternoon's presentation, The Many Lives of Mavis Robertson, is presented by Dr. Alice Garner, a 2023 National Library of Australia Fellow. The National Library's Fellowship program supports experienced researchers to make intensive use of the libraries rich and unique collections through 12-week residencies. These Fellowships are made possible by philanthropic donations, and we thank all our donors for their generous support.

Alice Garner is a historian, performer, and teacher based at the University of Melbourne's Graduate School of Education. She has published books on French social history and Australian and US educational history, and recently has been engaged in projects on union education, mentoring, and diversity in the teaching workforce. She's currently researching the life and times of Mavis Robertson AM for an audio documentary series. Mavis Robertson is perhaps best well known for her pioneering role in compulsory superannuation, but as Alice will reveal, there's much more to her extraordinary life. So please join me in welcoming, Dr. Alice Garner.

Alice Garner: Thanks, Bronwyn, and thank you to the Library for giving me this incredible opportunity. I've enjoyed my time here immensely, and it's gone way too fast. So this was my idea, to take one whole of life interview from the National Library collection, which holds over 55,000 hours of recordings and build an audio documentary around it. To use one life as a central thread and then bring in other voices. A curation from other existing oral histories, music and archival tape of all kinds, new interviews that I'm recording, as well as commentary and narration where it's needed.

If an interview's already publicly accessible and can be heard in its entirety through the National Library website, then there's no point replicating that. So during my Fellowship, I've been exploring how I might delve into and explode outwards from one person's chronological life story in an imaginative and respectful way, and where necessary, a critical way.

And I hope to use this existing oral history material in a way that will encourage more people to delve into the National Library collection themselves to go straight to the source because the National Library is here for the benefit of everyone. And once you realise what's in the coffers of this building, you wanna shout it out to the rooftops, like, "Get in here, everyone, and have a look. It's really amazing." And the material is not deposited here to gather dust, but to be listened to, read, examined, analysed, to contribute to current debate, artistic practise, community building education to help us figure out who we are, who we have been, and who we might be in the world.

I will explain why I chose to focus on the life of Mavis Robertson. But first, I wanna tell you about my first introduction to the oral history collection here. Back in 2009, I joined a research project based at Latrobe University and initiated by Diane Kirkby on the history of the Australian US Fulbright Exchange Program. And the National Library was a partner in an ARC linkage project. Part of my job description was to record a series of whole of life interviews with Fulbright scholars in different disciplines from across the six, or then six, now seven decades of that exchange program. So I went travelling around the country, meeting and recording the stories of a very interesting bunch of people, not just about their exchange experiences, but about their whole life from birth through to the time of our interview: childhood, schooling, family relationships, first jobs, study, travel, parenthood, or not working life, retirement the whole bit. And so I discovered the pleasures of sitting in a room, listening to someone talk through their life. Someone I had in most cases never met before the day I turned up with a black case containing a recorder, a couple of microphones and a bunch of cables.

I realised pretty quickly that for most of the people I interviewed, this was the only time they'd ever been listened to quite like this for hours on end without interruption or with very little interruption. I might occasionally ask a question or prompt for more detail, but I didn't try to control the shape of the telling. So the narrators had the chance to unspool their own particular version of events without being contradicted.

And I learned that it was important to let people talk in detail about aspects of their life that might not be of a special interest to me personally or to whatever project I was working on, which could be useful or interesting to other future listeners. And that can take you in all sorts of directions.

But with the Fulbright project, when it came to writing up the findings, and I did a lot of archival research for that too, in the Department of External Affairs as it was back then. It turned out that most of the life stories I had recorded, despite their inherent interest and value, couldn't sort of fit into the structure of the book that we ended up writing, which was really an organisational and diplomacy-focused history.

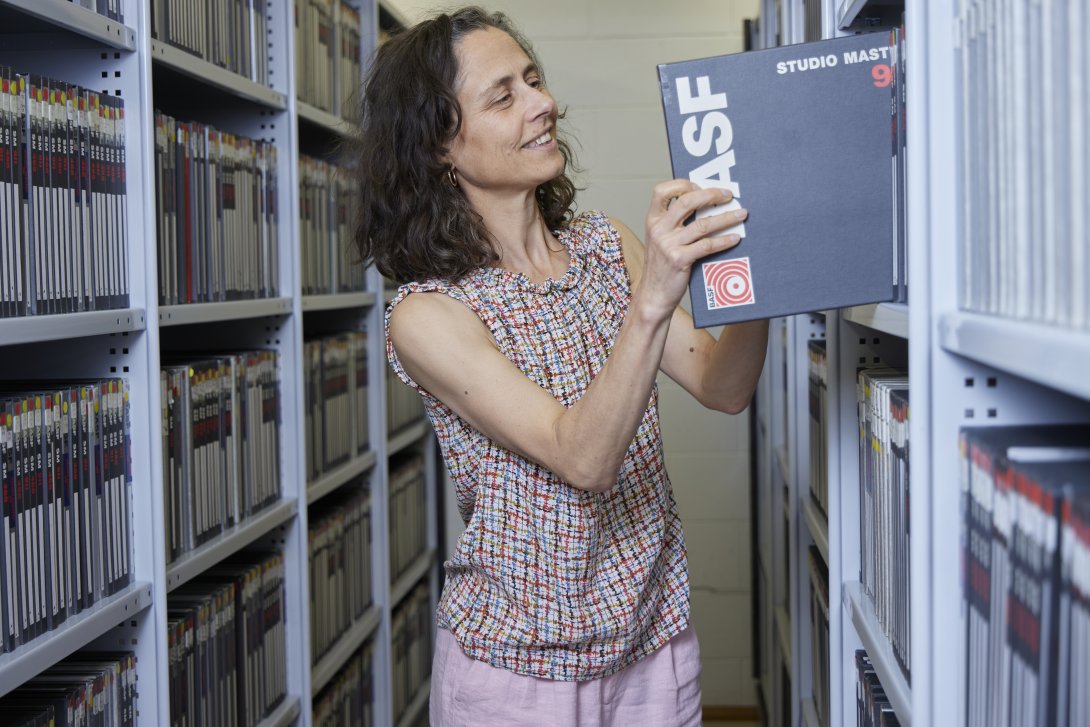

And so for a long time, it stayed in the back of my mind that there were all these really fascinating life stories sitting in the Library's, temperature-controlled storeroom, which I had the chance to visit recently, life stories that many people wouldn't know were there and might not even know to look for. And this was the seed of an impulse to create something new and accessible to a wide audience out of existing recorded life stories to be led by a life as lived, or rather as recounted, and make that the starting point for a research journey, rather than trying to squish a life story into the shape of a project devised from some other impulse. And that's something, obviously, that biographers do all the time. But the difference here is that I would be focusing on the sounds of that life story.

I'm under no illusions about the reliability of oral history as a source and in fact, you will have noticed that the library makes a point about this when you go to listen to their online version, it reminds you that it's a personal opinion and not intended to present the final verified or complete narrative of events. Just as in written material and autobiographies, people can be self-serving in their telling. We'll never get to the whole story because there is really no whole story unless you're prepared to fully live that life again.

The way we understand our own lives changes over time. We forget important things sometimes because it's convenient, other times because we just haven't activated that particular moment or experience. So the memory hasn't been reactivated or consolidated. But oral history recordings do offer something special and important when we research the past.

When we listen to recorded interviews, rather than just reading the transcript, which a lot of people do, we hear someone actively making sense of their life. They are recorded in the act of remembering and constructing or reconstructing their life in the form of story. And we notice the texture and the timber of the voice, an accent that might tell us something about origins or about a changing or changed identity, the speaker's pacing, their hesitations, shifts in dynamics, surges of emotion, or sometimes an unusual lack of emotion. All of these help us get a sense of the person as a person in a way that I think is quite different from a published autobiography, for example, which has been sort of smoothed out in the editing process. And where once upon a time, historians would often record an interview, transcribe it or have someone else do the transcribing, and then throw out the tapes, keeping only the corrected transcript, I think now there's a much stronger appreciation for the value of the audio recording itself. And certainly, the Library appreciates that and looks after them carefully. And with a boom in podcasting, that awareness of the importance of preserving audio archives has sharpened.

So what I wanted to do, and what I've been trying to do with this project is to start with a life story as recorded, and then pick out the moments, experiences, and reflections that reveal something about the larger world that this person lived through. And of course, we can't rely on this one account alone. So while this oral history might be the starting point, it's leading to a wide ranging search for other voices and perspectives.

So why Mavis Robertson? I was having a coffee last year with a friend, a retired union official, Max Ogden. Some of you may know him, he might even be there in the audience. Our conversation had turned to the lives of influential Australian women and Max said to me, "Someone really should write a biography of Max Robertson." Sorry, not Max. Well, he's written his autobiographies. He's all right. “Someone really should write a biography of Mavis Robertson”. Now, I didn't know who she was, but when he told me that she had taken him and 20 other young Australians on a delegation to the Vienna World Youth Festival in 1959, travelling through China and then on the Trans Siberian Railway across the Soviet Union, my ears pricked up. My work on the Fulbright project had given me a fascination with Cold War era exchange experiences and all the politicking that went on behind the scenes to make those things happen.

So I went looking for information on Mavis Robertson, and one of the first things I found to my joy, 'cause I think I started with Trove, was that she had recorded a whole of life interview for the National Library in 2003 with Sarah Dowse. I listened to the whole seven hours of it, the digitised version, which is accessible to anyone through the Library catalogue. And I treated it a bit like... No, I'll go back, back to here. Sorry. I treated it a bit like a podcast, half an hour listening while walking the dog, another half an hour while washing up. And there were stories that jumped out at me and that made me curious to know more. And I realised that Mavis had been involved in so many different campaigns over the 20th century and early 21st century, that her life story could serve as a departure point for an exploration of significant moments in Australian and international political and social history. Perhaps this was a life that would lend itself to an audio documentary series of the kind I had been imagining.

I just wanna draw your attention to this bottom image here. Kate Wood, very kindly, dropped off a bunch of badges with this image. If anyone wants one, come and see me afterwards.

So here are some of the things that Mavis was involved in that I could explore using her oral history as a backbone: the peace movement in Australia from the mid 1940s onwards, including early campaigns to ban the bomb and end nuclear testing in the Pacific, later people for nuclear disarmament, Pacific Peacemaker Campaign, the Peace Bus, the Palm Sunday rallies of the eighties, the Eureka Youth League, sending delegates to international youth and peace festivals throughout the Cold War and Eureka Youth League camps. She was a leader of the league, which among other things, their camps were significant sites in the folk music revival in Australia. So there's a whole musical thread here, too. Political censorship of literature and journalism in Australia. She was very closely involved with both Frank Hardy and Wilfred Burchett. So there's some very interesting stories to be told there. Living with ASIO surveillance, she and her husband, Alec Robertson, who was a communist journalist and a peace activist, were under constant watch and have bulging ASIO files, the anti-Vietnam War movement. And I know there's at least one person who is very actively involved in that, who's here today, and I'm sure there were more of you. She was on the organising committee for the moratorium in Sydney. The early days of Women's Liberation, including battles for abortion law reform, and I'll come back to that, founding of Women's Refuges and campaigns for women's financial independence. Also experiments in collective living, which in her case was not entirely successful, which is another story, an interesting one not for today. And of course, the Communist Party of Australia's growth and decline from the mid forties through to 1991. Now, she left the party in '84, but she still had an interest in what was going on after that. And in particular, some moments around the party's efforts to carve out an independent line after the invasion of Czechoslovakia in 1968. There's a really important story there. Not only that, but the Chilean Solidarity Movement after the Pinochet coup in September, 1973, Mavis was involved in arranging for safe haven for refugees, but also organising tours of Chilean musicians around Australia, raising funds for the communities living in exile, documentary making with cinematographer Martha and Sarah. They went to Vietnam in 1981 to film a documentary.

There's a shift after that early eighties period. She leaves the party in 1984, and then she moves into the promotion and management of union pension funds and then into the negotiation and development of industry and compulsory superannuation, so through the eighties and nineties. And she continued in that sector right up until really her... I mean, her retirement. But even after that, she was clearly still interested in what was going on. She was very involved in opening up women's leadership opportunities and mentoring networks and involved in the founding of Women in Super. And they went on to establish the Mother's Day Classic raising funds for breast cancer research. So, there's so much. And I have to mention, as a Melbournian Richmond Football Club, which was a very important part of her life.

So you can see why maybe Mavis' life might lend itself to this sort of exploration. But of course the challenge is how to work out which elements of her life and which events to focus on and which parts of the story will interest my imagined audience. It's my imagined audience keeps changing. Can you be my imagined audience? Now, this is where the constraints and the possibilities of an audio-based project come into play because making an audio documentary means making something that works for the ear. So I'm not writing a book and I'm not making a TV documentary, I'm making an audio documentary or maybe nonfiction podcast. And so today, I really wanna talk about how that has been shaping my research here in the Library 'cause I've been able to delve into the collection to roam, follow all the sorts of leads and marvellous threads. But my focus has been on mining the audio archives primarily, but not only oral histories. I've jumped on any audio recordings that might shine a light on aspects of her story.

And along the way, I've also been recording new interviews with people who knew or worked with Mavis, some of which will end up here, and some in the Noel Butlin archives where her papers are kept. I've got to know Mavis' son, Peter Robertson, who gave me permission to read her papers, which are at the Noel Butlin and who also supplied me with pretty much all of the photographs of Mavis that are in this slideshow. So I really thank him for his support. I'd also like to acknowledge Rex Hewitt, who's been immensely helpful as I progress through this. And the Australian Studies Institute at the ANU gave me a visiting Fellowship so I could spend some intensive time with her boxes.

So I followed, in some ways, a standard historical research process, working through her papers and fleshing out a timeline and identifying themes and questions. But in researching with an ear to audio, I've been led to down some different paths than I might otherwise have taken if I'd been trying to write a book.

I've been listening to a lot of existing oral histories that are in the collection here with people who were in the Eureka Youth League or in the Communist Party, or active in the Peace Movement or the Labour movement, or involved in protests against the Vietnam War or in Women's Liberation. So many stories. And of course, those interviews were not recorded with my project in mind. Most perhaps don't mention Mavis by name, but I'm listening to them as a way of understanding the world that she inhabited. So I'm not ready to pull all the threads together yet. There's so much- I'm in the middle of quite a complicated process. But I did wanna give you a glimpse of some of the voices and sounds that I hope to weave together.

First, there's Mavis herself who recorded a whole of life interview in 2003, 12 years before her death. This was with Sarah Dowse, who I also had the lovely opportunity to interview myself. Alongside this, I've been able to listen to two other interviews with Mavis. One recorded in 1981 by Barrie Blears, who was writing a history of the Eureka Youth League, and who knew Mavis very well. Mavis, as I mentioned, had been a leader in the Eureka Youth League in the fifties and early sixties. Barrie deposited his papers on the league here and in one box were all his interview tapes. You can imagine my delight when I saw there was one that had Mavis name on it. I opened the box and there were no tapes, but it was all right. So what they do, if it's in manuscripts, often they'll take the tapes out and put them in cold storage and look after them. So they digitised the files for me. And I also have another interview recorded with Mavis, which is not in this collection, but it was recorded by Sue Wills who was working on a history of the first 10 years of Women's Liberation in which Mavis was very active. And that was an important moment because it brought a lot of sort of theoretical challenges for communist women in particular, but also personal- well, opportunities and challenges all mixed up together. I know there's probably other tapes out there in people's garages, so please get in touch if you're interested in sharing a recording with me.

I mentioned the existence of multiple interviews because when someone is interviewed several times, the historian can compare their accounts and glean quite different things. Some stories people tell become locked down through repetition, particularly if they are interviewed more than once. But if an interviewer asks new questions, new details emerge. And in a moment, I'm gonna demonstrate this by drawing from two different interviews about one episode.

But first, a little bit of background. Mavis Moten was her birth name, was born in Melbourne in 1930 to Irish Catholic parents who worked on the railways. In her interview with Sue Wills, Mavis described her mother Claire as an Irish rebel and her father John as an Irish conservative. As a young woman, Claire Tilley, Mavis' mom, had been an apprentice teacher, but was displaced by return servicemen after the first World War. She ended up working in the Victoria Railway Refreshment Services and she wasn't gonna let the same thing happen to Mavis. Claire was very focused on getting her children a good education. And Mavis won a scholarship to Tintern an Anglican Girls School. Funnily enough, it was at Tintern that her political education was really kickstarted in ways her parents had perhaps not anticipated.

Mavis was 15 in 1945. Like many, she was deeply affected by the bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki ending the war in the Pacific. She read Wilfred Birch's articles about what he saw when he went in as the first non-Japanese reporter on the scene. Now, as many of you will be aware, Burchett had a very complicated life that was caught up in Cold War ideological battles. Something I will need to explore further because he did play a significant role in Mavis' life and she in his. And just to let you know that he was interviewed by Hazel de Berg and you can listen to that interview. I've just put a little snippet here from Mavis' a little... I think a speech or an article she wrote after Burchett died that talked about the impact of his journalism. And certainly, that was the sort of spark, I think, for her that sort of led her into the peace movement was learning about the effects of the bombs.

Now, when she was at school, she remembered that her interest in politics and in war and peace was noticed by two women in particular. And now you'll hear from her interview with Sarah Dowse.

[recording begins]

Mavis Robertson: I became a friend of Dorothy Tugan and her mother was a communist. I was surrounded by them. My history teacher was also a communist and I didn't know that at the time, of course. This was, of course, in the latter stage of the Second World War and the early years of the Peace. But it was my history teacher whose name was Constance Stewart, who suggested to me that I should consider going to a youth organisation where people discussed history and politics, the things that I seemed to be so interested in. And that's actually how I got to go to the Eureka Youth League.

[recording ends]

Alice Garner: She then makes an admission, which I think is an important one.

[recording begins]

Mavis Robertson: But to be perfectly honest, I think the real attraction of the Eureka Youth League at that time for me was the Graeme Bell jazz band. And when I found that they were going to an international festival of young people for peace and friendship in 1947, and somebody asked me if I would like to help in arranging an art exhibition to raise money for them, I was hooked. This was the way it all went. So these were influencers on me and they were all part of my education.

[recording ends]

Alice Garner: So then she talks about being swept up in the activities of the league, finishing school, getting a variety of jobs in a biscuit factory, a tomato cannery, and also the Queen Victoria Hospital for women, where she witnessed the terrible consequences of illegal abortions and experienced that informed her later campaigning for abortion law reform/ Enrolling at Melbourne University, she joined the labour club, which despite its name, had many Communist party members and many of them were return servicemen who had seen the party as the strongest voice against fascism. Mavis joined the CPA in 1949, which is, in many ways, an interesting time to join 'cause that's when things got even more difficult. And she would remain an active member until 1984. In 1949, she won a seat on the University of Melbourne Student Representative Council and and played a part in organising the 1950 Peace Conference in Melbourne. And there she heard Jessie Street speak about the warmongering big boys. Mavis was very influenced by Street and was instrumental in founding the Jessie Street Trust, which was in around 1989. And Street's Papers are here too. So her lifelong peace activism Mavis was certainly entwined with her membership in the Communist Party, but it was not entirely contained by it. Her many boxes of peace material in the Noel Butlin archives and not for the faint of heart. There's a PhD in those boxes if anyone's looking for a topic. In the early eighties, Mavis was named a vice president of the International Peace Bureau, and she was awarded several prizes for her peace work over the next two decades.

But going back to that late forties moment of joining the Eureka Youth League and getting involved in raising funds for the Graeme Bell jazz band was an important turning point. So I wanna come back to that by playing you an excerpt from her interview in 1981 with Barrie Blears. At the beginning, she's talking about the headquarters of the Eureka Youth League, which were then at 104 Queensbury Street, North Melbourne.

[recording begins]

Mavis Robertson: And I did go to 104 Queensbury Street, and I wasn't as last breast, actually. It's interesting in retrospect because the story has it that at that time, the Eureka Youth League was not a party political organisation. My very precise experience was that I went to a study class, which I think was called The History of the World Revolution. I'm not absolutely sure. And as I had no political background other than things that I had read, I asked some questions, which were clearly questions that shouldn't have been asked. For example, about Trotsky and so on. And I thought the response of people was such that they were very strange. And I didn't go there again until maybe a year or so later when a girlfriend of mine told me about a jazz club and asked me would I like to go. And we went one Saturday afternoon. I was a school girl and I was quite surprised to find that this place, 104 Queensbury Street, which had these political people in it was then called again, I'm not sure with my memory, but I think it was called The Uptown Club. And I was very interested in the jazz and the people, or should I say the males.

And I started going there on Saturdays. And one day, somebody, who I later found out was Stein, came up and said to me, "Oh, you are very interested in all this, aren't you?" And told me this great old story about how they were going to send this band overseas and they were going to participate in a big world meeting and so on and so on and so on. And it was all about peace and friendship and crossing over barriers.

Now, what you have to understand is that I was schoolgirl, it was 1947, it was Cold War; and it all sounded to me very dramatic and interesting. And what I was actually asked to do is help organise an art exhibition, I think. The point really was, they I was asked to do something and I was made to feel important. And so I was more or less in from then on.

[recording ends]

Alice Garner: I just think it's interesting what different details you get in an interview that has a particular focus. Even her accent sounds a little bit different. And where she pauses and where she... Anyway, birds in the background, there's a lot to get out of it.

At the end of that last excerpt, she touches on something important, the fact that at the Uptown Club, Harry Stein asked her to do something concrete, that this made her feel important and capable. That's certainly something she applied later in her own life when kind of the way that she related to other people younger than she was. Another thing she did as a result of these new connections was to help assemble Frank Hardy's book, "Power Without Glory," when it was banned by the census. Now, this is in 1950 and I thought librarians and book collectors might like this little story, so I'll just play this one

[recording begins]

Mavis Robertson: My friend Jan, whom I'd met at university, and I became part of a team of people. We used to go to work in the basement of a building owned by one of the building workers unions, up a laneway in Melbourne. It was all very dramatic. And we used to walk around these long tables by hand picking up the various sections of this rather large book, getting them ready for binding. And it is true that people can find some of those early books where one section was out of place or one was upside down. I don't admit to anything, but people used to say it was probably Jan and I who did it 'cause we were always talking. This was the first time I'd ever been involved in something where there were actually bodyguards, people with guns. It was a serious time.

[recording ends]

Alice Garner: In her earlier interview with Blears, Mavis reflected on her idealism as a teenage girl, implying that somewhere along the line, she might've lost some of that. The dramas of the Cold War might've seemed exciting at first at the Uptown Club and stitching Hardy's book together, but it would become harder to bear later. And there were quite a lot of disappointments to come, losses, personal and political. And if we just think about the jazz thing that brought her into the fold of the league and the Communist Party at that very time, it was being banned in the Soviet Union. So there's all sorts of contradictions and things to sort through.

She talked at some length about her struggles at different points with the Soviet model, with party line, with internal divisions here, contradictions in her own decision making. I can't explore it here, but that's something I will be looking at.

But I do wanna turn to another interview that gives a little insight into developments after Stalin's death in 1953 and after the publication outside of the USSR of Khrushchev's Secret speech in 1956, which acknowledged really the brutality of Stalin's regime. It's coming at this from an unusual angle, I think. But when Barrie Blears, I interviewed Barrie Blears who'd interviewed Mavis, he had been an electrician and he did maintenance on the Queensbury Street headquarters of the Eureka Youth League in Melbourne. And I realised he would know the building inside out. So I asked him to imagine himself walking through the building and after describing the main room where the dancers were held, which had a stage at one end and alcove tables and so on, Barrie went on to describe what he remembered.

[recording begins]

Barrie Blears: There was a basement and you went down to the basement, you go out to the backyard, which is pretty hairy. And of course, the toilets were out there. And yeah, it was the bookshop, the international bookshop had deposited a great stack of starland stuff there that we took years to get rid of.

Alice Garner: When you say that, when did they put it? Was that-

Barry Blears: Oh, I mentioned, I don't know, just trying to think. Probably in the sixties. But it's stuff that they couldn't sell and of course typical of the left already of me, but they didn't want to chuck it straight down the tip, so they dropped it with us and we'd chuck it down the tip.

[recording ends]

Alice Garner: So it's these sorts of stories that I'm keen to locate that give you a sense of being there, but also show how people were responding to events in the world around them. In this case, a sort of long overdue and rather disorganised rejection of a Stalinist past told through the fate of a pile of books. So the story of Mavis' political evolution and battles within the party and so on. It's an important story and one I'm still trying to piece together.

But when Mavis made a shift into the world of union pension funds and industry superannuation in the 1980s, which is where she spent her final decades, and where she carved out a very significant place for herself, including becoming the first fund secretary, or what we would now call CEO of the newly merged Cbus.

She brought with her a set of organising and negotiating skills honed from decades as a party functionary in very challenging political circumstances, a good deal of her political, sorry, her party and peace work had happened at the international level on Youth and Peace Congress planning bodies and the like. There are many photographs of her sitting on panels as the only woman, no doubt she had to grow a thick skin to wield any influence in these highly politicised and often hierarchical and patriarchal settings. And here she's at a communist party, I think it's the 50th anniversary of the Japanese Communist Party. And she has some reflections there on the difficulties facing Japanese Communist women.

Many I've spoken to have described Mavis as having a very sharp mind and a brilliant organising capacity. I interviewed Dave Wirth the other day who worked closely with her on anti-nuclear campaigns in the eighties. He recalled her sitting in meetings, knitting, mostly staying quiet and then synthesising what everyone else had said to come up with a rock solid resolution that no one was prepared to counter.

Quite a few people said to me in interviews that if she'd not been in the Communist Party, but had perhaps been in the Labour Party, she may well have ended up a government minister. And she was a very active mentor to women particularly who went on to be influential in their own right. And I think she used the Harry Stein method she'd experienced in 1946, '47, of giving people something to do and expecting them to do it.

One party colleague who knew her well said to me in an interview, "Mavis was the sort of person who got things done. That doesn't always endear you to people. And it has to be said. Many people, especially, but not only women, had told me that they were scared of Mavis. Disagreeing with her took courage. And on a number of occasions, Mavis ended a long time friendship or association in hurtful ways."

I think she could just cut people. This is something Mavis doesn't really acknowledge in her interviews, which is not surprising, but it has come up regularly enough that I need to acknowledge that and try to understand that.

But she did have some very close and intensely loyal friendships. One of them, for example, with teacher and union official Bill Leslie. And there's a very warm correspondence between them in her papers. There was a group of women she met with regularly right until she died. And many of them, unfortunately, are not with us anymore.

I tried to understand some of her character. She did carry some wounds. Her father rejected her for some years in the 1950s when she formed a relationship with Alec Robertson because he was a communist, because he was a divorcee. And because he was 12 years older, there was a bunch of reasons why her dad didn't approve. In 1974, Mavis lost Alec to a sudden asthma attack. So she was 44 and he was in his mid fifties and that was a huge sadness in her life.

But rather than get sort of sucked into that territory now of pain and loss, I just wanna come back to the Library collection and how it's helping me get a bit of a sense of her world. So while I've been looking a lot or listening a lot to oral history, there are other archives I've been finding. I’ve found some funny bits and pieces, but things that have delighted me.

So here's a little something.

[recording of horse and cow sound effects plays]

It goes on for a while. Mavis' husband Alec played a lead role in the first production of Reedy River, a musical that was the longest running show in Australian history at one point. I'm not sure if something else took over from it, but it featured the Bushwhackers and it was a special favourite of, I think, especially left-Wing families, but maybe not only left wing, who went to see it many times. It was a big part of the folk revival in Australia. That photo is not from the production Alec Cuisine, it's from a later one.

But Peter Robertson, their son, remembered Mavis often singing songs from Reedy River. And in the Library's collection, there are recordings of different productions of Reedy River. There are interviews with people from the Bushwhackers. I particularly enjoyed listening to Chris Clem's interview about what it was like being on the Eureka Youth League camps and what it meant as a teenager, the sort of affection he experienced from that community. That was actually quite a moving interview. So these are the sorts of things that I'm looking for that can bring some life to an audio documentary.

Now, Mavis was not a musician, but music is this thread that goes through her life as we've seen the jazz concert that brought her into the league. And as a both Eureka Youth League leader and in the party, she got to meet some pretty famous musicians. Her husband Alec toured Australia with Paul Robeson in 1960 when he came out here. And there's some wonderful audio here of Robeson talking and singing. And also Pete Seeger visited their house. And here I wanna play a little excerpt. Oh yeah, here's a nice picture of the Austral Singers at one of the Eureka Youth League camps. I wanna play something from an interview I did with Mavis' son, Peter.

[recording begins]

Peter Robertson: We had a very busy and open house in Balmain. It was a terrific house to live in. Balmain was that sort of a suburb. As I said, everyone's door was open after the pubs closed and the pubs closed at six o'clock. Anyway, people would come around to your house and there would be meetings, there was always meetings in our house. And there were lots of parties. I remember in 1961, so I guess I'm five years old now, standing in the lounge room of our house in Balmain in my green and black chequered dressing gown and pyjamas being introduced to Pete Seeger, the folk singer in our lounge room who'd come. He was on tour in Australia and obviously had performed a concert and then he'd come back to our house after the concert with half of it seen, the lounge room was full of people and there was music. There was always music, lots of music. And so, yeah, I remember Pete Seeger playing a song in our lounge room.

[recording ends]

Alice Garner: Not only music but poetry. I was very excited when I found in the papers of Jeffrey Dutton here, the audio from an episode of the ABC TV program spectrum on the 1966 visit of the Soviet poet Yevgeny Yevtushenko. There's Jeffrey Dutton with oral history tapes, but also just a reminder that you can find audio in the manuscripts collection. Always look in the finding aids.

Now, Yevtushenko came to the Adelaide Writers Festival on Dutton's invitation from what I gather. And he declaimed his poetry in Russian to huge crowds. Now, he was actually a bit of an international star. Now, I hadn't realised this until I listened to this audio program. Now, he was walking a bit of a tightrope really because he was internationally famous, but he was also being quite critical of the Soviet regime. I did wanna use a clip from that audio, but I'm still negotiating over the licencing. So hopefully, I'll get to that when I get to produce the documentary.

But it gave this sort of flavour, I mean the accents of the people who were speaking, the Australian poets who were mulling over this Soviet poet who has this huge following and he's really kind of big. And whereas Australian poets tend like an intimate audience and it was quite just a fabulous. Anyway. And also you hear him reciting in Russian and you hear the interpreter and you hear a conversation in a hotel room where the reporter chases him down and he's reluctant to do an interview. But in the background is Frank Hardy lying on the bed. They've had a big night out the night before, so there's just this sort of sense of place and a time couple of years before the big upheavals of '68. So that was in about 66. But I do wanna play you from Mavis' interview. Whoops. Ooh, I hope it's there. Oh yeah, here it is, about another side of Yevtushenko's visit.

[recording begins]

Mavis Robertson: Here is just one example of something strange that happened and which some of the participants say could never have happened in other countries, even in countries like Italy, which were perhaps the leading voice for a Euro communist outcome. Yevtushenko, the Soviet poet, had come to visit Australia, I think it was earlier in the 1960s. It will have to have been 'cause I was still in the Eureka Youth League. And he went to the Adelaide Festival. He'd become a friend of Frank Hardy's. And they used to talk about all sorts of things.

And Frank Hardy suggested to me that it would be good if the leaders of the Communist Party informally could hear Yevtushenko's take on what was happening in the Soviet Union. We had a very big living room in our house at Birch Grove 'cause when we built it, most people didn't have big rooms. And we wanted to have a place where lots of people could come for meetings and to see my slides and things like that. So we organised to have a discussion of all the Communist party leadership, meaning their executive or political committee or whatever it was called in those days. And they were all guys accepting me. I wasn't on the executive at that time, but it was in my house so I was there anyway and I'd helped organise this. And Yevtushenko spent a whole afternoon talking in great detail about lots of things, including things like the Jewish question, the lack of democracy, the poor conditions of workers in the new areas, how people didn't even get their pay on time, all sorts of things. And he tried to explain as best he could why he thought this was, and more and more, I think, all of us were thinking about centralised bureaucracy and what it actually does. He was extremely frank. And I think it helped a great deal for the Communist party leaders at that time to feel they were on the right track, raising some of the issues that they were raising.

[recording ends]

Alice Garner: So here I think you've got an interesting example of sort of art life and politics all coming together. Peter, their son also remembered Yevtushenko's visit. His recollection is that he was a bit of a playboy kind of a guy. He was very urbane man, passionate, very articulate, but with a heavy Russian accent.

So I wanna be bringing these different stories together so we can kind of map out what was going on and how different people were responding to it.

The last piece of audio I'm gonna talk about, but I won't play for lack of time, but it's to do with when the Chilean band, Quilapayun, came out here in 1975. Mavis was very involved in the Chilean Solidarity Committee in Sydney, and she really was one of the main organisers for this tour. I just did wanna mention that Joan Jara came out with the band and spoke at each of their concerts. And Joan was the widow of folk singer Victor Jara, who had been murdered during the coup. And Joan just passed away last week and I think she was 96. And I want to thank Jeannie Lewis for letting me know. I mean, it's been in the news since then, but we had just been talking about her the day before. And so it just seemed a sad thing.

But in the Library's collection is a recording by Peter Parkhill of the Q&A session that followed one of these Quilapayun concerts. And in it, there's a really interesting interaction with the audience where a woman asks, “how do you envisage the changeover back to the popular government? Will it be violent or can it be done”... And she sort of hesitates and then the band member says, "Oh, I think that would be a special. We can talk about it afterwards," he says. You get this sense of what can be talked about in public and what can't. And that sort of line between entertainment and politics, which was quite complicated terrain. And there were all sorts of interesting and complicated tensions within the Chilean community as well as there are in every community, which Mavis was trying to navigate, too.

So I'm finding these wonderful pieces of audio. And I want to be, in some respects, led by them. But of course they can't be the only structuring principle. So this is something I have to work out. But I think that in digging out these sorts of nuggets, I'm getting a stronger sense of the time and place of Mavis and her world.

And I guess the more I delve, the more I'm asking myself, what is the price of an activist life? I think we all, in some way, need to be an activist about the things that we in our gut feel are wrong. But it can be very difficult to sustain that over a long period and especially over a lifetime.

Mavis certainly had her faults, but she did remain a committed activist in a number of fields throughout her life. And I think looking closely at her life can give us a bit of an understanding of what that takes, where the satisfactions and successes lie, but also what kinds of compromises, losses, and sacrifices come with that. So I look forward to weaving these threads together in the coming year or so to try to make sense of an activist life, a complicated life, but above all the life of a woman who got things done.

Bronwyn Ryan: Thank you, Alice. That was so fascinating. We now have some time for questions. And as this presentation is being recorded, please wait for the microphone to reach you before asking your question.

Alice Garner: Don't be shy.

Bronwyn Ryan: There's a question up there. There's one up there.

Audience Member 1: Thank you. Thank you so much for that presentation that it's amazing what you're doing to build the world out of Mavis' story and thank you for that. I found what you said about hesitations in oral history is very interesting. Were there any he hesitations in Mavis' histories you've listened to that you found interesting?

Alice Garner: What I realised the more I've listened to Mavis' interviews was that she's quite slow paced. She's thinking carefully as she speaks. And I think she was someone who was- liked to be quite controlled in that way. So she's not someone who goes into sort of flights of fancy or occasionally you'll get surges of a bit of emotion or laughter, but it does feel like the voice of someone who's used to being very considered in the way that she expresses herself.

So I think also, thinking from a sort of aesthetic point of view, like audio aesthetics, it's also really important for me to be weaving her tape in with voices that have different qualities and paces. So that's another consideration that you wouldn't normally when you're writing, you just putting the quote down and people can imagine it however they want. But when you're dealing with an actual voice in time, it's a different approach. But I'm certainly, like, I do tune in if there's a longer pause, it's the cogs, you know. how shall I put this? Yeah, I don't know if that answers your question.

Audience Member 2: Thanks, Alice. That was such a great presentation and just amazing inspiring project. I'm wondering as an historian and interviewer yourself about the difference between working with an interview that somebody else has done that's archived and working with interviews that you've done.

Alice Garner: Yeah, of course, when you listen to interviews that other people have done, there are moments where you have a question that the interviewer either... They may have had the same question in their mind, but they've decided to just let the flow continue. Because I think that's a thing as an oral historian, there's that question, do I jump in there and ask for more detail? Or if someone's on a roll, I'm better off letting- and then we can forget too to go back and clarify.

So yeah, of course working with existing oral histories, that can certainly be a frustration where they might touch on something you are really interested in and then keep moving. It's like, wait. But that's also where it's been great. And because Mavis was interviewed a number of times and for people's different books, there is the opportunity to sort of move between them.

But I think that's why I've become conscious in my own interviewing to try to imagine what other people might also be looking for. But of course, you can never know. Sometimes it can be frustrating with some interviews, not so much recent ones, I'd say, because I think maybe the Library has been clearer on sort of expectations around not interrupting too much, but there are quite a lot of older interviews in the collection where there's a lot of interrupting where the interviewer... Sometimes it's very interesting 'cause they'll give their point of view, but as far as getting clean audio cuts, it can be a problem. But I do enjoy listening to existing interviews also because it takes me into territory that I might not have thought to ask about. Yeah, mm.

Staff member: I have a question that's come through from Yvette Grant who's watching online. She says, "Given the role music played in her life, how do you see music as part of your audio documentary?"

Alice Garner: Yeah, I want it to be in there from throughout, but I suppose it's how to do that in a sensitive way that doesn't sort of overpower. Some of it will be, I guess, more transitions and atmospheric, but there'll be places, for example, when talking about Chilean music tours or talking about Eureka Youth League where there's an opportunity to give some space, or I mean there's so many wonderful recordings in here, for example, but also potentially for... And in fact I did have this situation where I realised for a talk I gave a while ago, I couldn't get the rights to a particular piece of music, but I could find the sheep music here and I could record a version of it myself on cello as a kind of something that represents that music from that time, but is not necessarily the original recording. So yeah, I definitely want that to be a big part of it. Thank you. Yeah.

Audience Member 4: Thank you very much. Yeah, it's working. Alice, I was just wondering in terms of, I guess, the big question, you may have an answer or you may not at this point, but in terms of Australian history from Mavis' life, is there anything that's come out so far?

Alice Garner: You mean things that weren't known before or-

Audience Member 4: I guess just it's really interesting how her life developed and the events which she's responded to. And so I wonder, does that tell you anything about Australian history in general as well?

Alice Garner: Yeah, look, I suppose what I'm trying to figure out is there are stories that people know about or that I might know a little bit about, but somehow sometimes when it's told through a life story, suddenly it hits you what that actually means or what it was like to live through that time.

So just a small example is that in '55, Alec Robertson went to China on a sort of political education kind of trip, 18 months. Mavis was pregnant with their son, Peter. She could not because it was actually illegal to go to China at that time. She couldn't tell anyone where he was, they couldn't correspond to each other. So she was essentially having to be like a single mother and her parents thought that Alec had left her. So there was some really difficult stuff.

And as I interviewed people, I realised there were a lot of children of parents, communist party parents, who had their fathers disappeared for a year and a half or two years and they came back and met them for the first time. And I think that's something that never even occurred to me. And what does that mean for those families? What does that mean? I think that has some pretty profound consequences for families. So they're the sorts of things that you might know that people would travel to China or something if they were in the party, but not understanding the implications of that. That's just a little example. Certainly, I've learned a lot of things that I didn't know before, but maybe other people knew about them. I just didn't. Yeah.

Audience Member 5: Thank you, Alice, for an amazingly penetrated presentation. I was wondering in the recordings that you've heard of Mavis, if she reflected in any way on what happened in 1991 with the attempted coup in the Soviet Union and the end of the Soviet Union formally in December. I was working in the national office, joint office in those days of the BWIU and the Federated Engine Drivers Union. And I was there when that happened. And the particular three days was one of the most revelatory of my life. I was not a communist party member. I was one of the few in that office that weren't. But the revelations of people's behaviour and their conduct and what happened during those three days has just sort of stained itself in my memory. I was wondering if Mavis reflected on that period at all, given that although she wasn't a member of the party at that time and there were many others who weren't, who had been members of the party before. Given that it was such a tectonic plate shift, did she reflect on that period at all in anything that you've heard?

Alice Garner: I'm trying to remember now whether she... I don't know that she goes into it in a lot of detail in her main NLA interview. Certainly, I saw that around the 1968 invasion of Czechoslovakia, that was like the echoes of that and the pain in the memory of that for a lot of people that either I interviewed or have listened back to. Yeah, '91, in her papers. there's quite a lot of newspaper cuttings from that period. And I think some reflections in some letters. But thanks for asking that question, though, 'cause I might go back and have another listen. I do keep going back to the interviews and listening for different things and be interested to hear what you know, if you wanna have a chat afterwards, what it was that you saw and heard 'cause that might help me understand what the responses were. Interesting question. Yeah, thanks.

Audience Member 6: Thank you, Alice, for very good presentation. I'm just wondering in the interviews, does Mavis reflect on the impact on her personally and also on her activities, political activities of a pretty much a lifetime spent under surveillance?

Alice Garner: She does talk about it. She doesn't talk about it in a lot of detail, but there are moments when I think... And actually I've interviewed Peter about this as well. And perhaps I sort of understood it more from his interview than from Mavis herself, how consistent that was, that surveillance that they were used to. There was a car outside their house all the time with someone watching and they knew their phones were being tapped and all of that. So she does talk about it on a couple of occasions and she does talk about later problems with trying to get a visa to the USA, for example, and some of the implications further down the track of having a security record. And I'm actually in the process of, I'm waiting or the files are being transferred from ASIO to the National Archives at the moment. There's a lot of them. So I will get that story from the other angle, I suppose, I think it's weirdly, I think she must have got used to it. I mean, living with that level of surveillance must grind you down. Yeah. Mm.

Staff member: Hi. I've got one more question from Joe Kowalski who's also watching online. I love how you acknowledge the complexities of Mavis' character. What was the process whereby you landed on knowing you needed to make that acknowledgement?

Alice Garner: I think because enough people, I think when you interview a lot of people and you have a lot of conversations and something keeps popping up, even people who continued to stay close to Mavis would recognise that that was part of her, that she could be quite hard on people or that she would cut a friendship, or that people were scared of her. I mean, there reaches a point where you go, "All right, I can't ignore that. It's clearly part of her personality and her story." And first, I was a bit nervous about that, and then I thought, you know what, no, I mean, I think you just have to work with the sources and reflect what you hear. And because I didn't know Mavis, so I didn't have a preexisting sense of her. So I'm relying on other people's stories and on her account, and I'm just doing my best to kind of make sense of that. Yeah.

Audience Member 7: Sorry, I'm just wondering, when you say that you ask people to have other accounts, if there's other stories we know about, like actually someone was telling me yesterday about a meeting that Doris Lessing went maybe in about 1960, but she sounded really like that meeting at Mavis' house. And so I'm just wondering, with all your oral histories, if you know, if you're reading it and listening to it, is there a place where you can record? Have you looked into this? I was there and this was my account of the event, or I happen to know that somebody else was there and they've made it public their account. With the National Library with your oral histories, have you got a space where people can do that?

Alice Garner: Ah, okay. So in a sense, to respond to an existing thing and to... What a fabulous idea. Yeah. That's something to think about, isn't it? If you could have some kind of response collector, I guess the thing is you would need to have with it because of course when you record an oral history, there's a consent process, so there'd need to be an inbuilt consent at the time of putting in the submission. So there'd be a bit of. I don't know if anyone, Bronwyn. Yeah, so it's a really good idea though, because sometimes people will just have one story that they want to contribute. I've had a few people say, "Look, I didn't know Mavis well, but I have one memory that I think I'd like to tell you this one story." And I think those are often really interesting and important stories as well. So I'm collecting those as they go. But yeah, what an excellent idea. Hmm. Pass that one on to the oral history unit.

Bronwyn Ryan: Great questions there. So as we draw to a close today, a few quick plugs before we leave. Next week, we'll host our final Fellowship presentation for the year, which we hope you can join us for. On Thursday, the 30th of November at 4:30, comics journalist, cartoonist, and labour activist, Sam Wallum will talk about his 2023 Creative Arts Fellowship. This Fellowship has involved research into the Pink Bands movement and will contribute to a new artwork, celebrating the unlikely 1970s Coalition of Blue Union workers and LGBTQAI+ people. If you wanna catch up on our other recent talks by the National Library Fellows, you can find these on the library's website, as well as on the library's Facebook page and YouTube channel. So please join me again in thanking Alice Garner for a really, really fascinating talk today.

Who was Mavis Robertson?

If you haven’t heard of her before, Mavis Robertson AM (1930-2015) is perhaps best known for her pioneering role in compulsory superannuation and for co-founding the Mother’s Day Classic fun run. Alice first learnt of Mavis from a friend of hers who had known Mavis in the 1950s, when they were both a part of a group of young Australians who travelled across China and the Soviet Union to the Vienna World Youth Festival. Intrigued by these stories, Alice went looking for more information, and came across Mavis’s 2003 whole-of-life interview in the Library’s oral history collection.

Listening to the collection

This wasn’t Alice’s first venture into the oral history collection, having used it and our manuscripts collections to research the history of the Australian-US Fulbright program 15 years ago.

‘My earlier academic training was in French history so I had spent a lot of time in French archives and libraries, but when I shifted my focus to Australian history I began to realise what a treasure trove you have here in Canberra.'

'There is always so much more here in the collections than you might think'

It was during this venture into the collection though that Alice really uncovered the full extent of audio recordings at the Library. Across the oral history and manuscripts collections, Alice found all sorts of content for her audio documentary, including music, speeches, meetings and more. Among these, Alice found the voices of many people who knew or moved in the same circles as Mavis, some telling stories like those that inspired this project to begin with.

'One favourite find was in the papers of Geoffrey Dutton: a 1966 recording of a program about the visit of Russian poet Yevgeny Yevtushenko, who came out here for the Adelaide Festival, and who (I know from other sources) visited Mavis’s house to talk secretly with Australian Communists about what was really going on in the USSR. The recording gives a fantastic flavour of the times – the way people spoke, how Australian poets responded to this suave, internationally famous and very performative Soviet artist, as well as the political complications of his life as a touring artist who was critical of the regime back home and yet not exiled.'

Finding answers and connections

At the end of her time as a National Library Fellow, Alice had nothing but good things to say about her experience. ‘The opportunity to dive into the collections and stay in the research bubble over a good length of time is a wonderful gift’ made better by the ‘really helpful and encouraging’ librarians. Further, Alice greatly enjoyed meeting and learning from other Library Fellows, often finding 'many surprising connections’ between their diverse subjects.

Read more about the National Library’s Fellowship and Scholarship programs.