On 15 August 1968, Prime Minister John Gorton officially opened the National Library of Australia; the first major construction along the shores of the four-year-old Lake Burley Griffin.

Press cuttings from 1968

The Library holds press cuttings about the opening. Many superlatives were used in reviews, which largely praised the design and purpose of Australia’s new national showcase and treasure trove.

“Nomads come to rest at last”, proclaimed the Sydney Morning Herald (SMH); “their wanderings going back to 1901” and “at one stage some of the books were stored in a disused morgue and the films in an explosives shed by a quarry”.

The National Library’s years of uncertainty “in the wilderness”, including a short-lived home on Kings Avenue, were finally over, and now the libraries of Australia could concentrate on, as many reported, the “great task ahead”. In a special feature in the SMH, ‘Australia Unlimited 1968’ (pages 67-68), of the Sydney Morning Herald (22 July 1968), the opening of the National Library was seen as the beginning of Canberra becoming “a thriving city”.

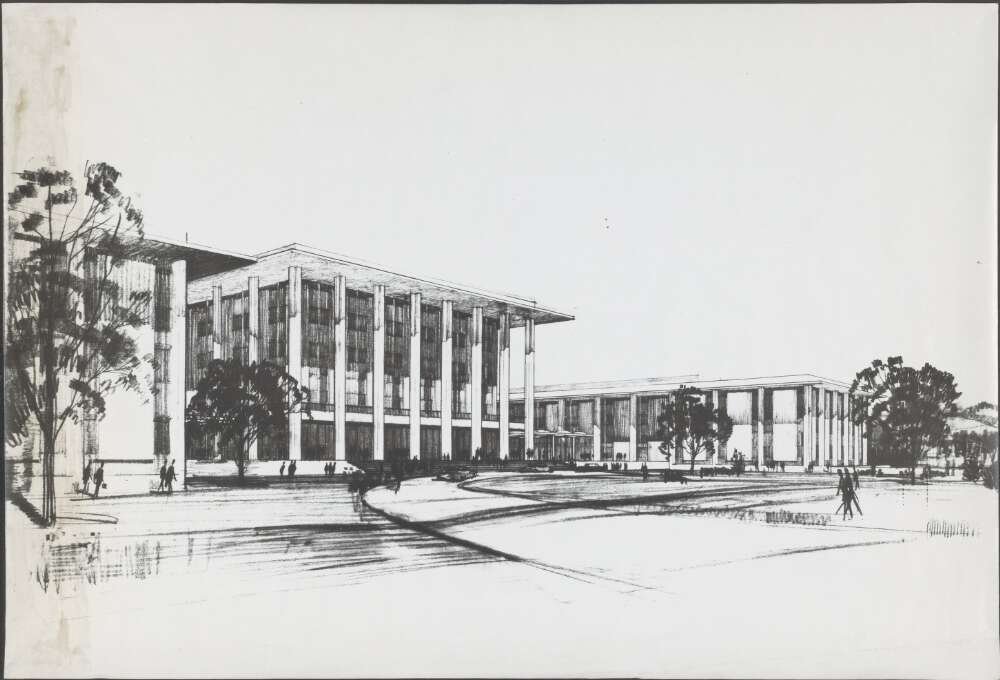

“National Library Opens Today” proclaimed the front page of The Canberra Times. A four-page supplement (pp. 27-30) featured advertorials for the builders and designers of the Library and an article describing our new “Storehouse of Knowledge” as “reminiscent in its marbled columns and classical façade of a great and wealthy bank”.

The National Library opened with “fanfares of trumpets”, wrote Laurie Thomas, arts editor for The Australian. “A page in history” had been turned and “in a welter of metaphors”, “the first of the monumental buildings planned for the Parliamentary Triangle” had arrived. Mr Thomas wasn’t entirely sure about the architecture and predicted arguments aplenty ensuing “about how right or sane it is for Canberra buildings to try to go on looking Greek in the middle of the Australian bush”. However, he did concede, amongst the “dreary shapes” and “character of existing Canberra architecture”, the new National Library “stands right out”.

Hobart’s The Mercury declared: “CANBERRA – impressive, status-seeking, planned symbol of national control – has done it again.”

An emerging inland metropolis

Sir John Overall, the Commissioner of the National Capital Development Commission (now National Capital Authority), wrote that with the opening of the National Library in the “central triangle” and the plans for the new buildings, including an Australian National Gallery and a High Court, Canberra was “an emerging inland metropolis” for the 110,000 Canberrans and the “600,000 and more tourists” who were visiting each year.

Building the collection

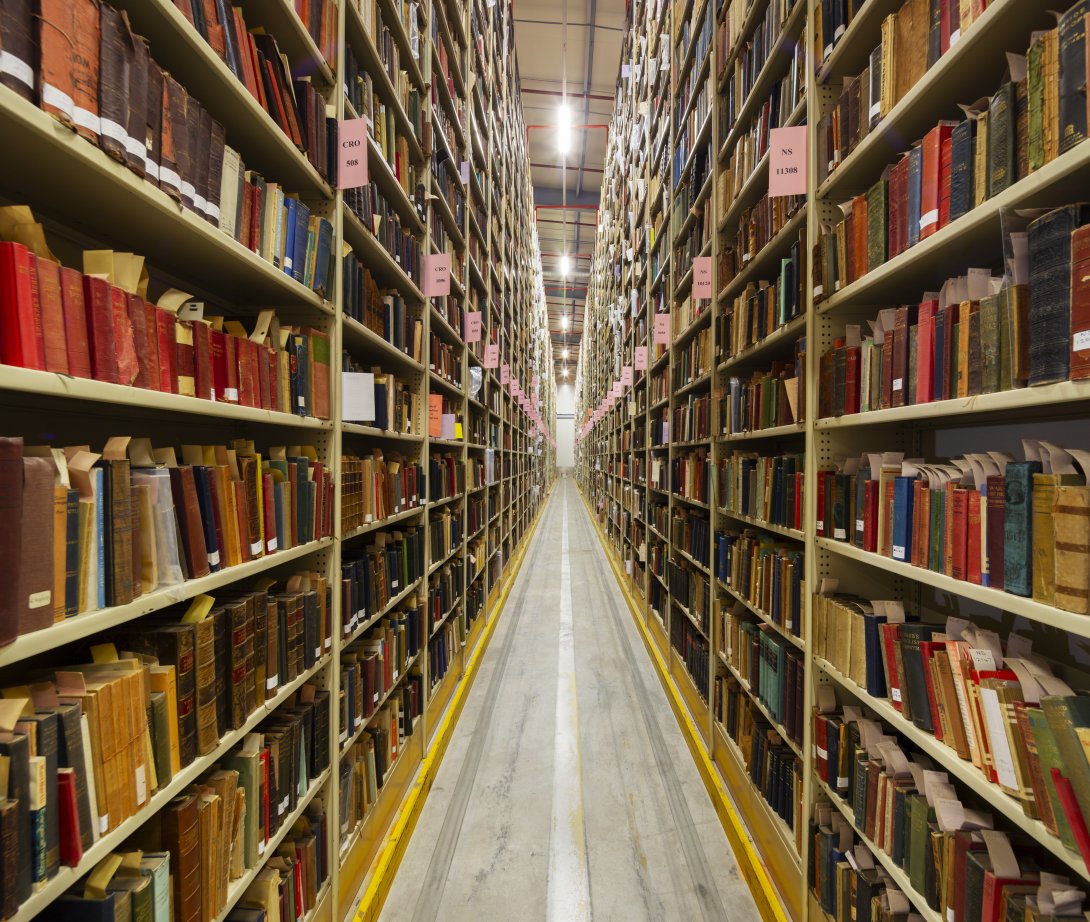

Sir Harold White CBE (1905-1992), the first National Librarian, spoke about the Library’s plans to increase the collection by 100,000 books each year, a goal made possible by Legal Deposit, a provision of the Copyright Act (1968) in which a copy of everything published in Australia must also be deposited to the National Library. (The Albany Advertiser, 12 August 1968, page 10.)

Journalists reported on this, and the plans for developing the historic collections to be stored in the “$1 million an acre” eight-acres of space, which included Captain James Cook’s manuscripts and Endeavour journal, the 1297 version of the Magna Carta (now in the Parliament House collection) and 11,000 French Revolution pamphlets. (Financial Review, 16 August and Geelong Advertiser, 12 August 1968.)

“They will swell the already extensive collection of literature, now totalling more than one million volumes. With them comes other treasure for the library – pictures and sketches, maps and manuscripts, photographs and ‘movies’, microfilms and microcopies. …The quantity and range of the material now on file is impressive, though the library still regards the collections… as being in their formative period.” (The Albany Advertiser, 12 August 1968, page 10.)

And swell the National Library of Australia’s collection has through legal deposit, government funding, or donations of their life’s work from artists, writers, academics, bibliophiles, collectors et al.

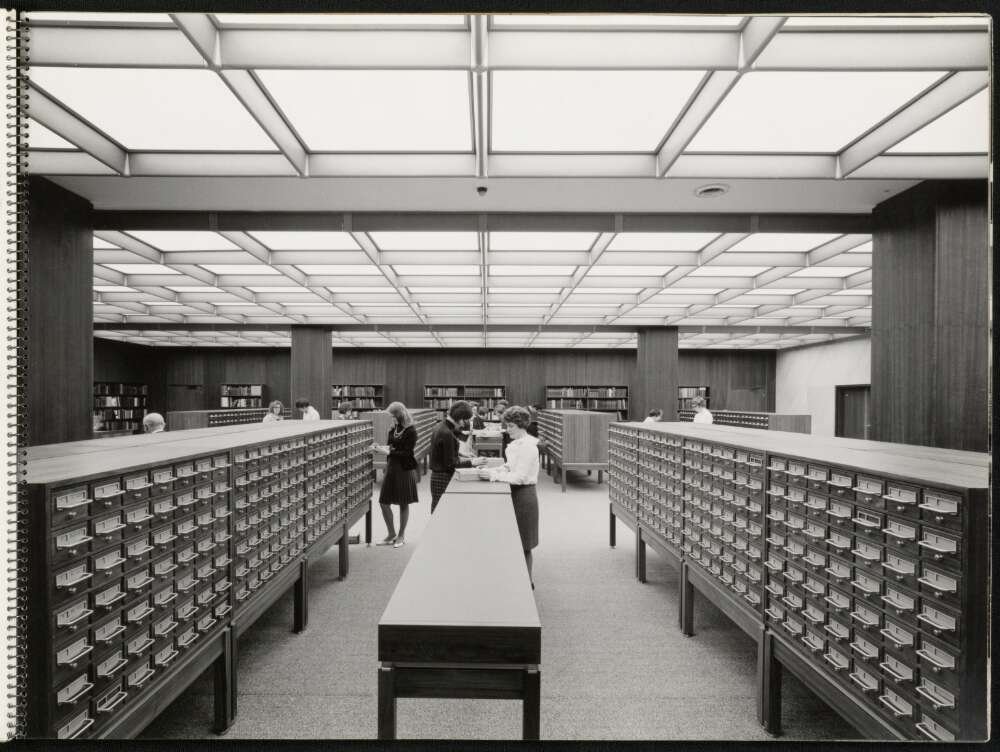

A computer network…

The Library’s computer network was also being planned. John Balnaves, “principal librarian (bibliographical services)”, said: “"A computer network would enable libraries to give much improved service to scholars and research workers almost immediately…For example, libraries would be able to provide almost instantaneously the titles and authors of books published in a particular language or in a particular place, things which at present they can do only after lengthy research". (The Canberra Times, 13 August 1968, page 7.)

Improving the services to scholars and research workers is something the Library continues to do, having recently launched a redeveloped catalogue and with plans for a whole host of new resources available via Trove.

We continue to maintain our building to safeguard the collections it houses for future generations. Keep up to date with our building works by subscribing to our newsletter or social media channels.

It is also the engagement, connection and donations from Australians that have helped the national collection to grow and to be shared across the nation and the world. So, thank you! And happy 55th to National Library of Australia building.