The correspondences encountered within the Library’s collection are sometimes incredible. I have been looking at the prints made by the French artist and naval man Charles Meryon, (1821-1868) a remarkably fine etcher and sketcher whose works are not nearly as well-known as they should be. To some extent, the artist’s tragic and relatively early demise and mental health militated against his reputation, even though during his short life he was admired by figures as esteemed as Victor Hugo and Charles Baudelaire. Meryon’s revelatory images of mid-nineteenth century Paris, before buildings and streetscapes were lost and ‘improved’ by Baron Haussmann, are exquisite time-capsules of a sort. His ‘Views of old Paris’ are fastidious and engaging images which preserve a world largely no longer extant.

https://gallica.bnf.fr/services/ajax/pagination/page/SINGLE/ark:/12148/btv1b55002210j/f1.item (This is the etching Le Stryge, the vampire gargoyle on Notre Dame viewed via BnF Paris, via Gallica service)

At 17, Meryon joined the French navy and later made the arduous, but in his case, hopeful journey from France to New Zealand. Sailing aboard Le Rhin from 1842, the mission was to replace existing French vessels protecting Akaroa, on the Canterbury Peninsula in New Zealand. It transpired the French military outpost was not a place of action and exotic charms but rather boring, but it did give Meryon time to draw and paint and dream of home. He even found time to carve a Maori-style canoe from a large log which Le Rhin’s Captain Bérard admired, and ordered for it to be returned to France, (into the Arsenal in Toulon for a time.)

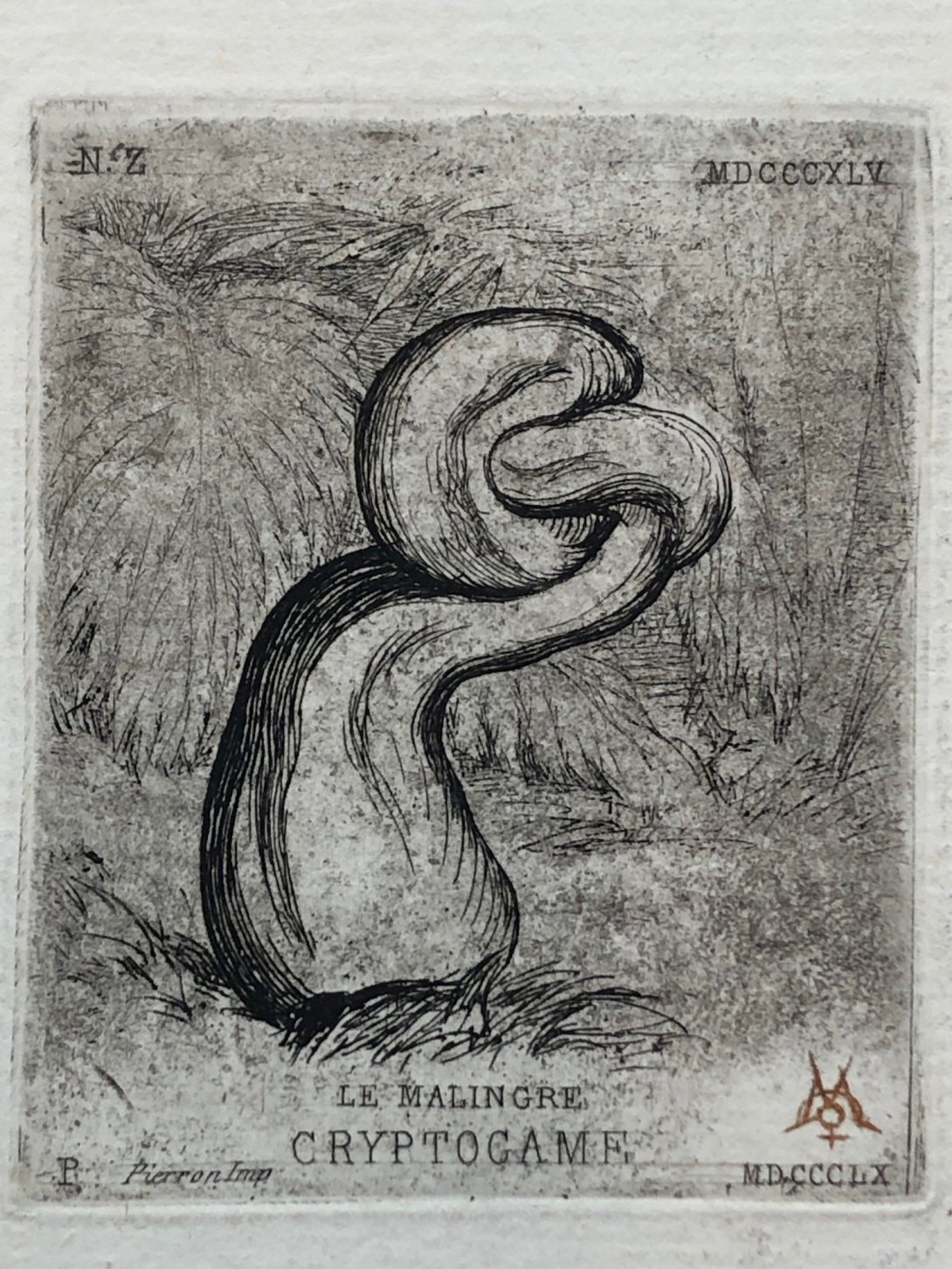

Within our Rex Nan Kivell Collection we have numerous items associated with Meryon including, most pertinently here, the etchings he created after the Le Rhin voyage – Le voyage a la Nouvelle Zelande (NK731/1). These prints surprise the viewer. They all are of interest but are inconsistent in size and, to an extent, in approach. The one that most caught my eye was Le Malingre Cryptogame, a tiny squarish etching, only 7 x 5.7cm and printed on a seemingly large sheet of paper. The image is obscure, abstract and I find it alluringly modern. Why did the bored young French artist, having visited the end of the earth, create such an image, especially when the whole suite only runs to 11 etchings? The title is enigmatic, even for a French speaker, Le Malingre Cryptogame. It sounds sinister even though the form depicted seems to reside somewhere between a natural history specimen and a contemporary sculpture - by Anish Kapoor or Tony Cragg perhaps? Translated into English as The Sickly Cryptogam, it is still not much clearer. A cryptogam is a form of plant such as algae, ferns, lichens and mosses, which reproduce by spores and has neither female nor male sexual organs.

Here is Meryon’s quote about Le Malingre Crytogame, which he discovered in the Akaroa forest:

“in one of the walks which I used to take in order to pass the time at the end of our sojourn in Akaroa… I saw in the corner of a wood of lofty forest trees this poor little fungus. Its ephemeral existence probably only dated back to the morning which had followed a rainy night. Distorted in form and pinched and puny from its birth, I could not but pity it. It seemed to me so entirely typical of the inclemency and at the same time the whimsicality of an incomplete and sickly creation that I could not deny it a corner in my souvenirs de voyage, and so I drew it carefully.’

The cryptogam etching, produced years later, can be read as a form of cryptic self-portrait. The pinched form mirrors Meryon’s self-criticism and doubts about his worth and success as an artist.

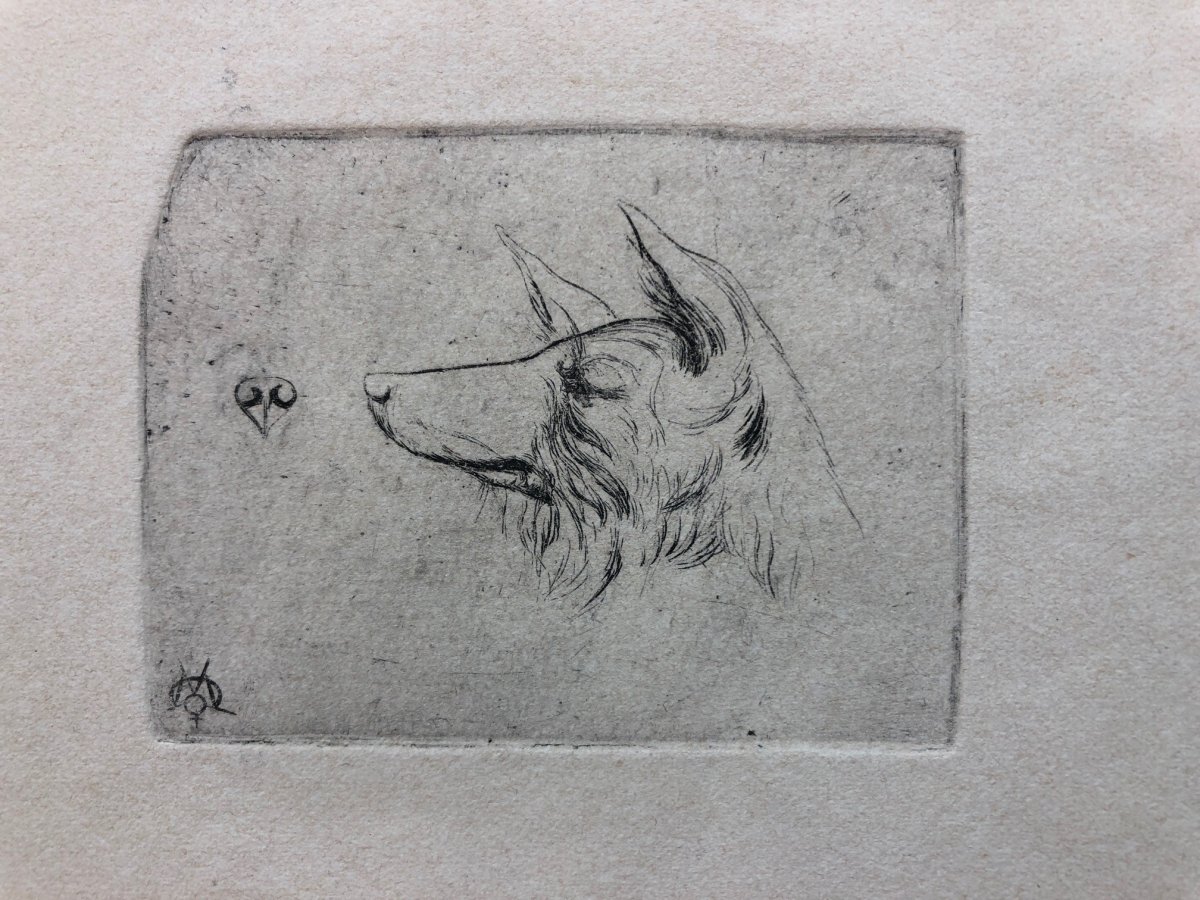

Charles Meryon (1821-1868), Tete de chien de la Nouvelle-Hollande (Dog of New Holland), etching (reprint) 1964, Rex Nan Kivell Collection; NK10430 (Plate from: Le voyage a la Nouvelle Zelande)

Meryon, who was colour-blind, was to return to his drawings from Le Rhin and Akaroa and to translate eleven of them into etchings about fifteen years later, the little cryptogam amongst them. We have a copy of it thanks to Rex Nan Kivell’s remarkable collecting of the minutiae of Pacific and Australian life. He acquired all of the images including, the Dog of New Holland etching, which was missing from his collection and which he managed to get reprinted from the original etching plate by an associate, in 1964. Nan Kivell’s collecting was a testament to the long game, he left no stone unturned in his attempt to assemble, piece by piece, his version of a distant world. A world he had left in 1916, never to see again.

The Dog of New Holland was probably drawn aboard Le Rhin after it was acquired in a side trip to Sydney. The ship’s canine companion, named Noroît, (meaning Nor’wester), looks like a fairly typical hunting dog of the colonial period in Australia. Such animals were bred for speed and size to be able to take down a large kangaroo and were usually a cross between a greyhound, wolfhound and deerhound. They were not dingoes though may have had some dingo genes in their makeup. Meryon had visited Sydney spending almost a month there in late 1843, a respite from the boredom of Akaroa. He purchased wax and Plaster of Paris to sculpt heads on his return to New Zealand, expanding his repertoire. These busts of Maori no longer seem to exist, but Noroît, with his detailed snout, clearly engaged Meryon’s attention for a time. The fact that poor Noroît was washed overboard and drowned during a storm, no doubt impressed his features on Meryon’s mind all the keener. Sadly, the wonders Meryon saw abroad were not to make him immune to the distractions of his middle age, and the dementia and delusion which followed, crippled him.

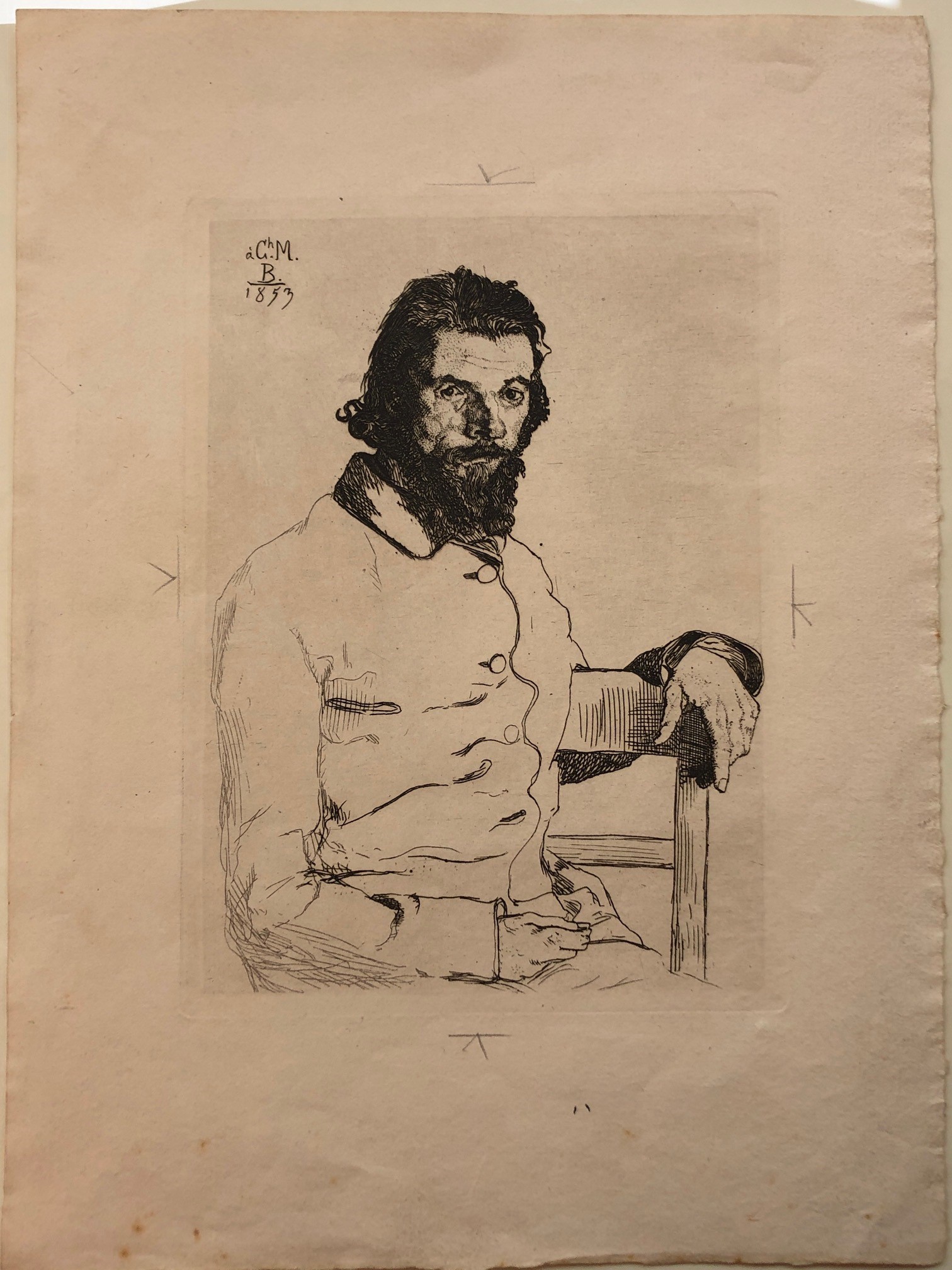

Félix Bracquemonde (1833–1914), Portrait of Charles Meryon, etching, 1853, Rex Nan Kivell Collection; NK4205

Within the collection, we have two portraits by Meryon’s friend Félix Bracquemonde (1833–1914). In 1853, Bracquemonde memorably and permanently captures the strong gaze and facial features of his older friend and fellow etcher. Tragically, Meryon was to die 15 years later in an asylum, starving himself of food and imagining his god had asked this sacrifice of him. He was only 47. A friend, a fellow sailor composed an epitaph for him,

‘His boat flooded in an instant, and quickly sank.’

To return to the surprise hinted at, at the beginning of this piece, I searched online to clarify what a cryptogam actually was. Within a reference in Wikipedia, the first source which appeared, was this apocryphal story: ‘During World War II, the British Government Code and Cypher School recruited Geoffrey Tandy, a marine biologist expert in cryptogams, to Station X, Bletchley Park when someone confused these with cryptograms.’ A great story, but one which it seems may not be altogether correct. Following the links within the Wikipedia entry to its entry on Geoffrey Tandy, I found the rather improbably titled blogpost, Old Possum and the limbs of Satan written by David J. Collard in 2013.

http://davidjcollard.blogspot.com/2013/06/old-possum-and-limbs-of-satan.html

It transpires that Tandy, who worked as a botanist at the Natural History Museum in London, was a great friend of the poet T. S. Elliot. Elliot was godfather to Tandy’s daughter Alison and Collard raises interesting possible links between Elliot’s relationship with the Tandy family and mentions of them in his poetry. As I scrolled down through Collard’s blog reading the very interesting story, which was illustrated in part through Tandy’s papers held at the NHM archives, I found a photo which I instantly realised was taken from the National Library’s collection.

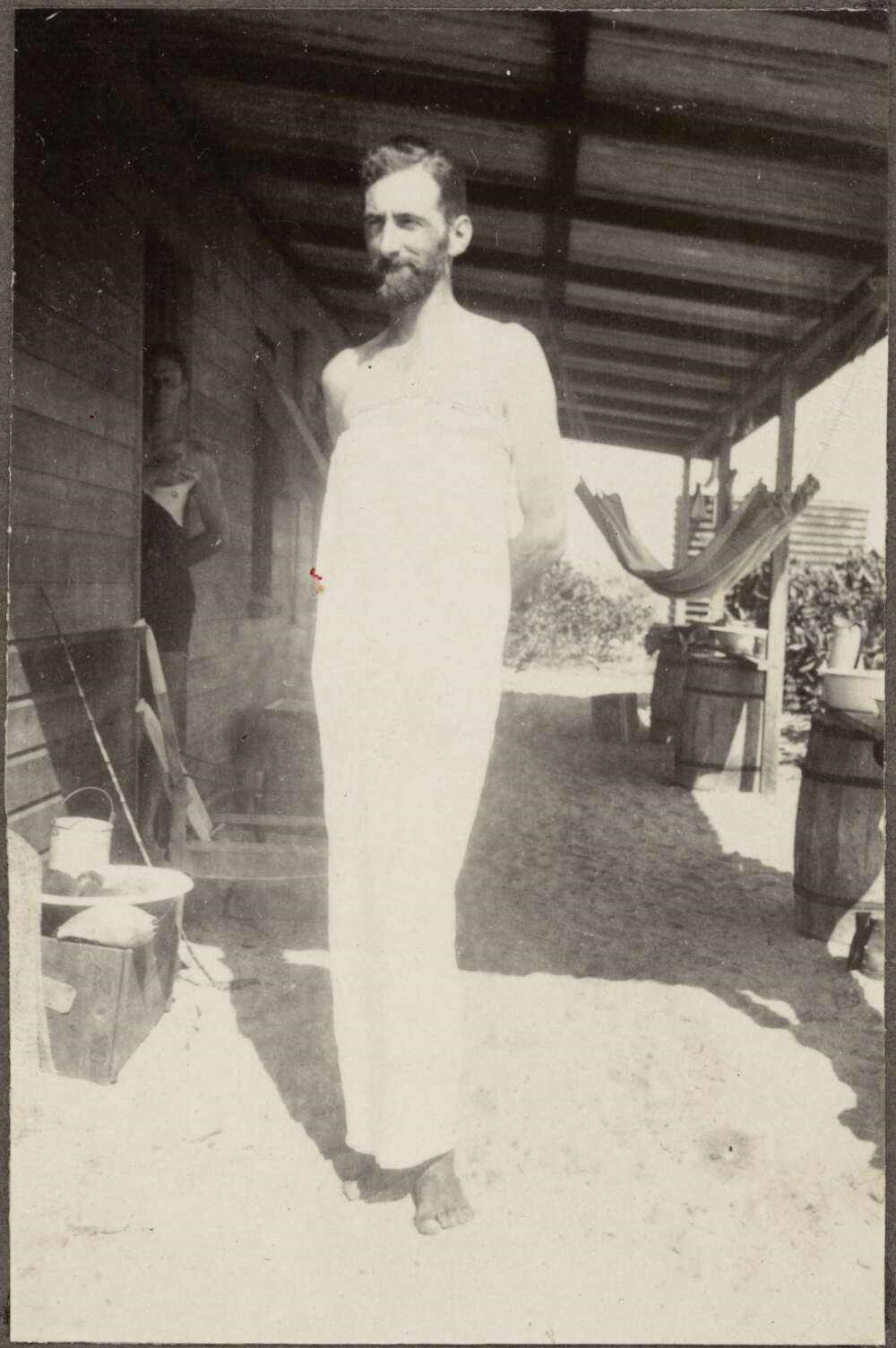

Unknown photographer, Geoffrey Tandy solves the heat problem with the aid of a bed sheet, 1928, gelatin silver photograph, in Presentation album to Mattie Yonge by the Australian Museum team who joined the Great Barrier Reef Expedition, Low Islands, Queensland, 1928,

Unfortunately, it was not hyperlinked to our original image so I backtracked through our catalogue and found this curious image of, ‘Geoffrey Tandy draped in a bedsheet’. It seems Tandy, as a marine biologist was a member of the Great Barrier Reef Expedition to the Low Islands in Queensland in 1928, and his presence is documented here in a number of the photos in the associated Presentation album presented to Mattie Yonge, by the Australian Museum team. (see http://nla.gov.au/nla.obj-144980308/view ) Collard’s blog about Tandy is certainly worth reading and, other than straightening out the misconception about the cryptogam vs cryptogram business, also makes the point that Tandy, single-handedly, had a fundamental role in shortening the horrors of World War 2. While at Bletchley Park, working under Alan Turing, the brilliant mathematician in charge of codebreaking, Tandy was able to use his skills as a marine biologist to help restore a rescued the Enigma Code Book. The British had captured this crucial document from a sunken German U-Boat and Tandy’s knowledge of waterlogged organic material and access to the right paper, enabled the book to be saved and for the code to be cracked. This serendipitous and singular event is regarded as giving the Allies a considerable advantage over the Germans and in ultimately shortening the war.

From Charles Meryon’s 19th century musings on the ‘puny’ cryptogam in Akaroa, to the brilliant work of a marine biologist in wartime Bletchley Park, the National Library’s boundless collections can certainly lead the researcher into unexplored waters from time to time.