Stephanie Owen Reeder’s Heritage Heroes series celebrates stories of incredible survival, persistence and resilience by young people. Courageous Kids and Their Amazing Adventures binds together the five original, beloved stories with two brand new ones. Meet the ‘courageous kids’ by reading an extract from each story below.

Brave Bee and the Castaway Kids

Will the Wonderkid and the Elusive Treasure

Amazing Grace and the Sinking Ship

Lennie the Legend and the Remarkable Ride

Marvellous Miss May and the Wondrous Circus

Clever Quong Tart and the New Gold Mountain

Valiant Jane and the Disappearing Trail

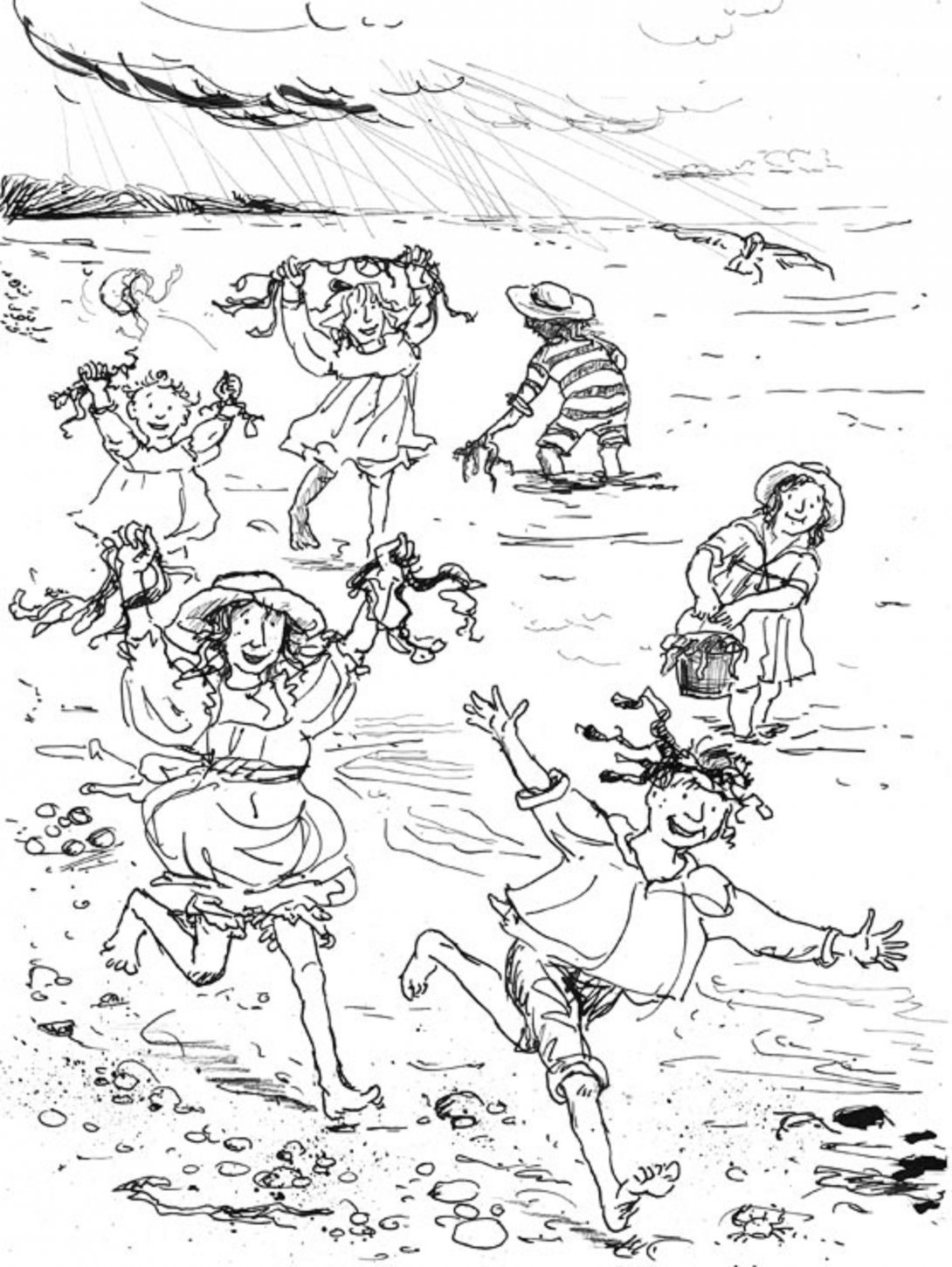

Brave Bee and the Castaway Kids

North-West Iutruwita/Tasmania, September 1895

Bee plodded along in the mud, dragging one tired foot after another as she pulled potato plants from the ground and tossed the tubers into a hessian sack.

She straightened up to rub her aching back, and stared in despair at the endless rows of potato plants still waiting to be harvested. ‘We’ll never get it done in time,’ she sighed.

‘You’re probably right,’ her sister Lydia said, tugging the heavy sack along the ground.

‘Watch out for the Potato Monster!’ Bertie yelled. He yanked a plant out of the red soil and threw it at his sisters. It plopped onto the ground between them, spraying them with dirt.

The girls looked at one another. ‘Get him!’ Lydia cried.

They chased their brother up and down the field, chanting, ‘We hate potatoes!’ at the top of their lungs.

Their father’s voice brought them to a skidding halt. He stood glaring at them, legs apart, hands on hips, his ginger moustache bristling. ‘Really, children! I expect better behaviour than that, especially from you, Belinda. You’re thirteen now, and that is not how young ladies behave.’

Lydia swallowed a snigger. There was nothing ladylike about her big sister. Bee’s long hair was a tangled mess. Her pinafore was streaked with dirt. Her stockings were sagging around her ankles. And her leather boots were coated in mud.

Pa shook his head. ‘If we don’t finish the harvest this week, there’ll be no holiday on Trefoil Island.’

‘Sorry, Pa,’ Bee said. She glared at Bertie. ‘We won’t do it again. Promise.’

Their father nodded and strode away. The children hurried back to where they’d left the sack and continued digging up the hateful potatoes.

A week later, Bee, Lydia and Bertie snuggled up in bed in the room they shared with their younger sisters, Jane, Winty and Sarah. They were heading off to Trefoil Island the next day, and they couldn’t wait.

‘We’ll have so many adventures,’ Bertie said. ‘There’s sure to be pirates’ treasure hidden there—and I’m going to find it.’

‘There aren’t any pirates here, silly,’ Lydia hissed. ‘They only sail on the high seas. Pa said so.’

‘Well, sometimes there are really big waves in Bass Strait. They can be this high.’ Bertie

stretched his arms as far as he could, dragging the quilt off Sarah. She squealed and kneed him in the back.

Ma appeared in the doorway, a flickering candle in her hand. ‘Enough! I don’t want to hear another sound. We have a big day tomorrow. Go to sleep. Now.’

As soon as Ma left, Bee tapped Lydia on the shoulder. ‘Do you think Ma’s having another baby?’ she whispered.

‘Bertie reckons she’s eating too many potatoes,’ Lydia replied.

‘What would he know?’ Bee said dismissively. ‘He thinks babies come from muttonbird burrows.’

Bee lay still, listening to the snuffling and snoring of the others as one by one they fell asleep. She finally drifted off too, but her dreams were haunted by the sound of crying babies trying to escape from muttonbird nests.

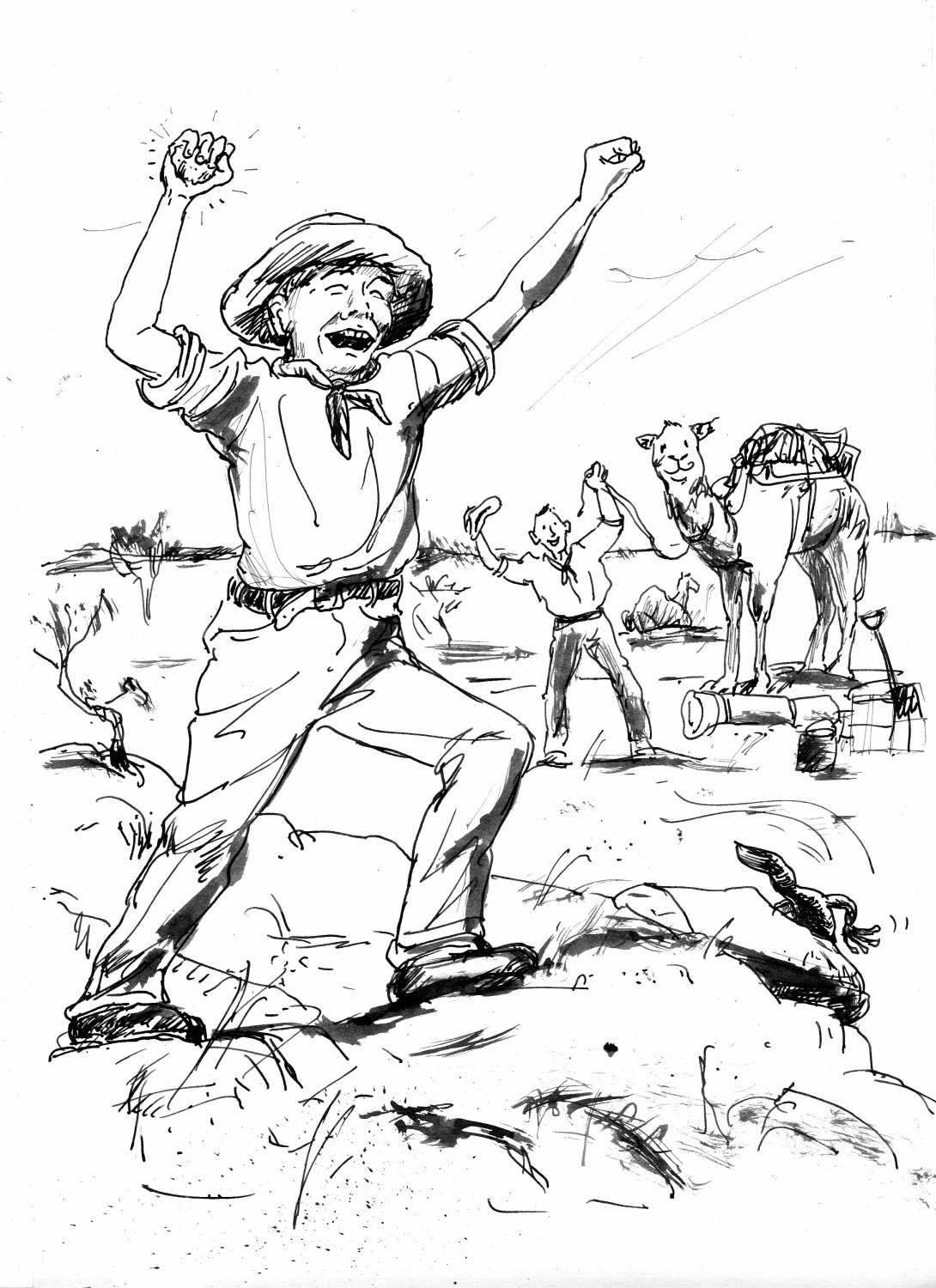

Will the Wonderkid and the Elusive Treasure

Great Northern Railway, SA (Kokatha Country), December 1914

Will Hutchison clutched the sill of the train window and rested his forehead against the cool glass.

Adelaide Railway Station was packed with people. Porters rushed back and forth across the platform, pushing heavy trolleys laden with battered suitcases, tea-chests and baskets.

Stockmen sauntered past, swags slung across their broad shoulders. Cameleers in colourful turbans hurried towards the train. Young men in new army uniforms chatted excitedly about the war in Europe. Their families huddled nearby.

Will checked that his food hamper was tucked securely under his seat. There was no dining car on the train. On this long journey, it was every man—and boy—for himself.

‘I hope McKenzie gets here soon—the carriage is filling up fast,’ said Will’s father. He consulted his fob watch, then peered out the window.

‘I hope so too,’ said his companion, Philip Winch. ‘It’ll take more than you, me and this whippersnapper to find gold in the desert.’ He glared at Will. ‘I’m surprised you let your boy come on this expedition, Jim. He can’t be more than thirteen.’

Jim ruffled his son’s thick, wavy hair. ‘Will’s fourteen,’ he replied. ‘And he’s a tough, athletic lad who knows his bushcraft. I have faith in him.’

‘I’m fifteen, Dad,’ Will whispered loudly, shaking his head. ‘You always get it wrong.’

A young man blundered into the carriage, tripping over Phil’s outstretched legs. ‘Sorry, mate,’ he mumbled. He threw his swag on the luggage rack above their heads and collapsed onto the seat opposite them.

‘Mr James Hutchison, I presume?’ he said with a grin, holding out a large, freckled hand.

‘Mr Melville McKenzie, I presume,’ Jim replied, with a wry smile and a strong handshake. ‘Welcome to the expedition of the New Colorado Prospecting Syndicate. Glad you finally made it.’

‘Mum reckons I’ll be late for my own funeral. Call me Mel—everyone does.’

Will wriggled around on the hard slatted seat. ‘Are we going soon, Dad?’

‘Shouldn’t be long now,’ his father replied. ‘Glad you’re so eager to get going. We’re off on one hell of an adventure.’

A whistle blew shrilly. Late arrivals hurried aboard, jostling and elbowing one another for a seat. A fug of dark smoke and soot drifted past the windows as the engine built up a head of steam. And then they were off, rattling slowly out of the station. The streets of Adelaide—bustling with horses and buggies, trams and newfangled motor cars—were left far behind as they headed towards the centre of the great continent of Australia.

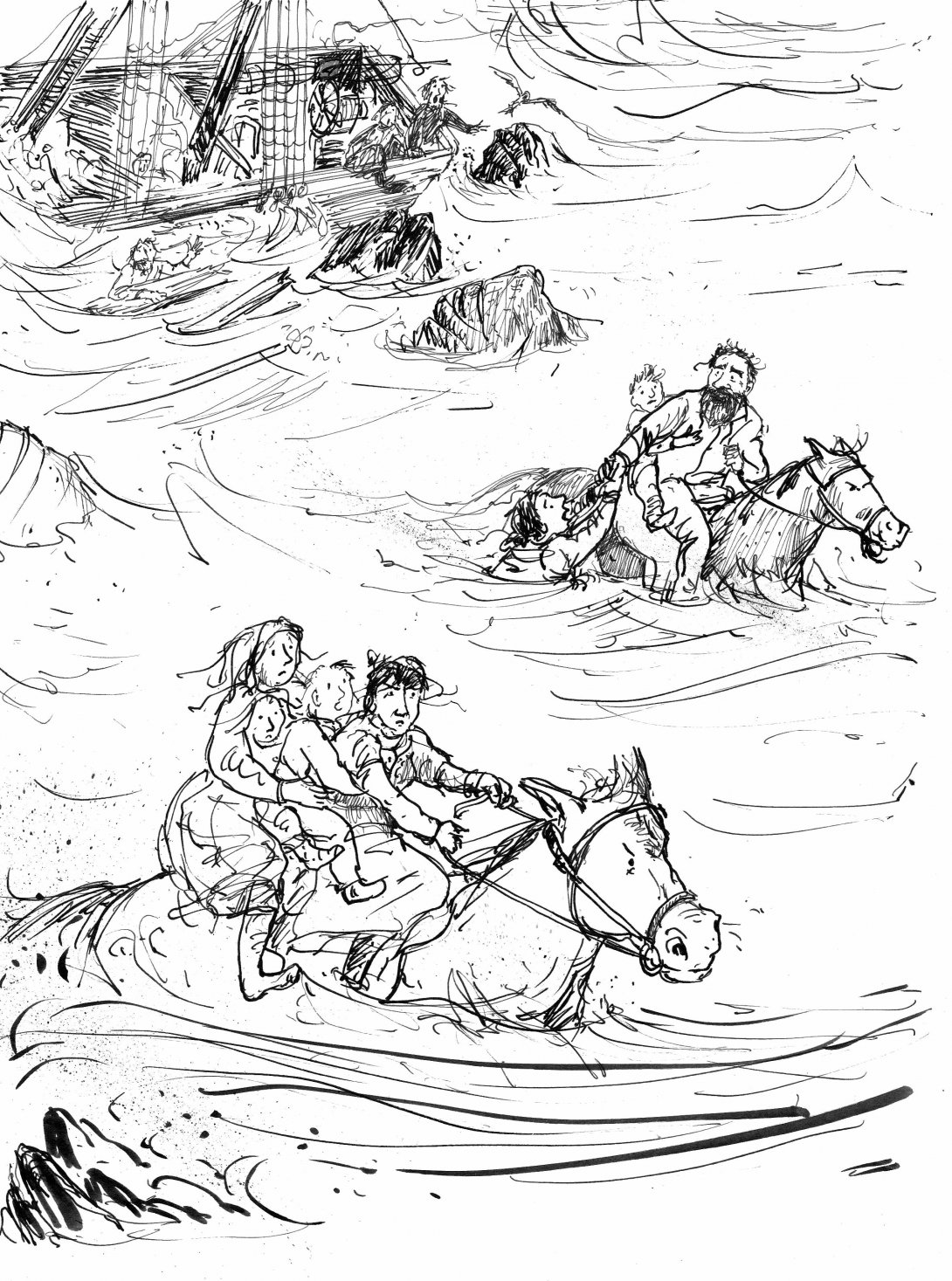

Amazing Grace and the Sinking Ship

Wallcliffe House, Margaret River, WA (Wooditchup, Noongar Country), Sunday 26 November 1876

Grace Bussell awoke with a start. All she could hear was the roaring of waves on the nearby beach and the

thumping of her heart.

‘Oh, no, not again,’ she groaned.

‘Was it that rotten nightmare about the sinking ship?’ her sister Charlotte whispered from her bed.

Grace shivered. ‘It was. There were children clinging to the sides of the boat and struggling in the water. The poor little things were so scared.’

Charlotte padded across the floor. Moonlight lit her way, shining through the chinks in the curtains. She sat on her sister’s bed and held her hand.

‘It’s only a dream, Gracie. And, if it ever came true, you’d be the first person on the beach trying to save them—you do so love a bit of drama! Now, go back to sleep.’

Charlotte was soon snoring gently, but Grace lay wide-eyed. The wind whooshed through the peppermint gums in the garden of their isolated farmhouse, and the sea thundered, wave after wave crashing on the nearby shore.

Grace tried to distract herself by listing the ingredients for the Christmas pudding they’d soon be making. ‘Raisins, currants, sultanas, sugar …’ she murmured, before finally drifting off into a dreamless sleep.

Bunbury Wharf, Monday 27 November

A tomcat slunk along the edge of the long wooden jetty at Bunbury, on the lookout for a fishy meal. He was sick of rats. He rubbed hopefully against the legs of a cabin boy leaning on a bollard.

‘Ahoy, Ginger,’ Jimmy Noonan said, picking up the cat. The wind blustered around them, throwing salty spray in their faces. The scruffy creature closed his eyes and purred.

Jimmy stroked the cat as he watched the crane driver load timber into the cargo hold of the small but sturdy steamship the Georgette. Over a hundred loads of wood had already been deposited deep inside the ship’s hold. The crane driver was eager to finish. It was nearly knock-off time, and he was ready for his dinner—preferably somewhere warm.

‘Steady as she goes!’ shouted the leader of the work gang. The crane driver spat on his hands and set the winch in motion to move the crane. It screeched and strained under the weight of an enormous plank of wood. Slowly twisting in the air, the jarrah beam swung out on its cable.

‘Looks a bit unsteady to me,’ Jimmy confided in the cat.

‘Lower away!’ came the cry.

The crane driver let the brake out a little and lowered the hardwood into the ship’s hold. But something went wrong. The giant beam landed with a jarring thud, and the little ship shuddered and shook. Jimmy shivered in sympathy, and the tomcat leapt from his arms and slunk away.

‘What are you doing?’ yelled the engineer on the Georgette. ‘You’ll put a hole in the ship!’

‘It wasn’t my fault,’ the crane driver grumbled. He rubbed his cold hands together and shovelled coal into the furnace that kept the donkey engine going. Then he carefully lowered the remaining timber into the ship’s hold.

Jimmy boarded the Georgette and headed for the crew’s cabin. The ship would soon be returning to Fremantle to pick up her passengers, and then the long journey to Adelaide would begin.

‘I hope nothing else goes wrong,’ Jimmy murmured, as he lay on his narrow bunk. He’d be far away from his family this Christmas. But for a shy lad like him, the ocean, the ship and the occasional cat were all the company he needed.

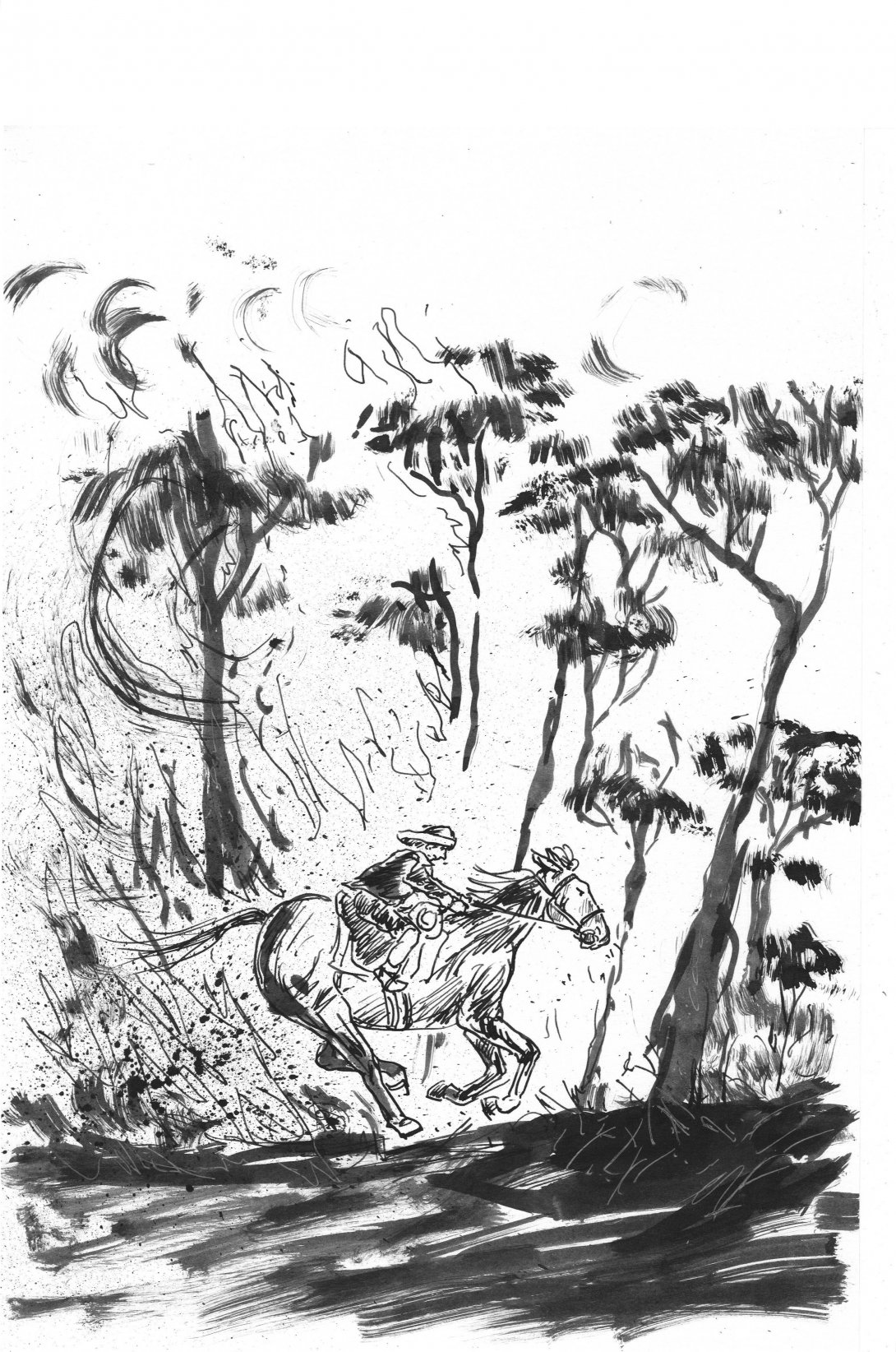

Lennie the Legend and the Remarkable Ride

Leongatha, Vic. (Bunurong Country), August 1931

‘Whoa, Prince!’ Lennie yelled. He tugged on the reins, trying desperately to stop the horse from skittering

sideways in the mud. But a scrawny nine-year-old boy was no match for a huge draught horse.

‘Calm down, you cantankerous thing,’ Lennie pleaded. ‘Mum’ll never forgive me if there’s another accident.’

Lennie’s shoulders relaxed as Prince finally settled into the same rhythm as the other three horses. Back and forth they plodded through the rich, brown Leongatha soil.

Lennie peered out from under his sou’wester hat. Rain needled his cheeks and dribbled icily down his neck. ‘What a way to spend the school holidays,’ he grumbled.

But he didn’t really mind. He’d had to do something when he found his mum in tears after his dad was taken off to hospital.

‘I’m worried about what’ll happen next year,’ she’d told him. ‘If we don’t finish the ploughing, we won’t be able to sow the potato and onion crops when your dad gets home. I’ve got my hands full already, what with the farm and you kids. And then there’s this rotten Depression.’

Lennie knew that some of their friends had lost their farms. He couldn’t let that happen to his family.

‘Don’t worry, Mum,’ Lennie told her, ‘I’ll do the ploughing.’

‘Are you sure? There’s still twenty-four acres to do. And you’ll have to be careful.’

Lennie nodded. He knew that ploughing could be dangerous.

After all, that was how his dad had come a cropper.

It had happened on a bleak winter’s day five weeks previously. Captain Leo Gwyther sat straight and tall as the horses pulled the plough up and down the paddock. But disaster was not far away. Hidden under the emerald grass was a twisted tree root.

The blade found it, the plough teetered to one side, and the captain tumbled onto the churned-up earth.

Lennie found his father when he brought him lunch. He was lying on the ground, one leg sticking out at a strange angle, his face the colour of peeled potatoes.

‘My leg’s broken. I heard it snap,’ his father croaked. ‘Unharness the horses. Then tell your mother what’s happened and ride into town and fetch the doctor.’

As Lennie turned to go, the captain grabbed his ankle. ‘You’re the man of the family now, son. Don’t let me down.’

‘Never, Dad,’ Lennie promised.

Now Captain Gwyther was far away in Melbourne, where nurses in starched white aprons made sure his broken leg set.

Lennie missed him—even though his dad was sometimes hard to live with. Lennie shivered as he recalled the screams of pain that sometimes came from his parents’ bedroom late at night.

‘I wish Dad would tell us what happened to him in the war,’ Lennie’s little sister Beryl said after one particularly bad night. ‘How did he get those scars on his hands? Why does he cough all the time? And why won’t that nasty hole in his leg heal?’

‘He must’ve done something really brave,’ Lennie told her. ‘King George doesn’t give medals to just anyone.’

Marvellous Miss May and the Wondrous Circus

Queensland, June 1900

‘It’s time to practise again, Miss May, otherwise you won’t be good enough to perform in the circus,’ said Bungaroo. ‘Do you want to be busking on the streets forever, child?’

May Zinga shook her head and smiled at the elderly Japanese circus performer in his colourful kimono. At six years old, she was already a practised acrobat. Her parents were both circus performers, and her father had started training May when she was only three.

Pushing her mop of thick, dark hair back from her face, May hopped onto the makeshift tightrope tied to the washing-line poles in the backyard of the family’s ramshackle house in Happy Valley. They were staying there while May’s ma, Dezeppo, recovered from giving birth to her fourth child, Gilly.

‘Higher, higher! Step, stretch, bend, step,’ Bungaroo admonished, tapping May’s legs with a stick as the little girl skipped across the trembling wire, clutching a Japanese parasol in one hand and an open fan in the other.

‘There will be lemonade and lollies if you get this right,’ Bungaroo promised. So May did.

‘Bet I can tie myself in more knots than you,’ boasted Arthur, May’s younger brother. He was practising contortions on a hessian bag nearby.

‘Never,’ May replied. She leapt onto the mat beside him, leant on her elbows, draped both her legs over her shoulders and tucked her feet under her chin. ‘Beat that!’ she said with a grin.

‘This is no life for a circus man,’ May’s father, Johnny Zinga, grumbled to himself the next day as he supervised May and Arthur. They were busking in the main street of Mount Morgan.

‘Look at that tiny girl,’ said an elegantly dressed gentleman. ‘She’s very clever for one so young.’ He threw a handful of pennies into the old hat Johnny had put on the pavement to collect money from passers-by.

‘Penny pincher!’ Johnny snarled as the man walked away. ‘That toff could’ve spared at least a shilling or two. I can’t wait to get back to the circus and earn real money again.’

He snatched up the hat and stormed off. May and Arthur scurried after him, trying hard to keep up.

‘Isn’t she marvellous?’ May sighed that evening. The children were watching their mother practising her acrobatic routine high in the air on the top rung of a long wooden ladder. The ladder balanced precariously on the soles of their father’s feet as he lay on his back, legs extended, knees locked, muscles bulging and a grimace on his face.

‘Again!’ he demanded. ‘If you can’t get it right, we’ll never get another job in a circus.’

Later that night, May lay in the bed she shared with her little sister, Ida, and her brother, Arthur. She was too exhausted to sleep. ‘Move over,’ she grumbled as Ida’s elbow dug into her ribs. Then

Arthur threw an arm across May’s shoulders. ‘No wonder I can’t sleep,’ she sighed. ‘It’s like sharing a bed with a snaggle of snakes.’

May was finally drifting off when she heard her parents arguing, yet again.

‘It’s time to get back on the road with the circus, Dezeppo. You’ve had enough time to recover from the birth of the baby. And old Bungaroo’s done a fine job training May. She’ll be able to earn her keep now too.’

‘She’s only six, Johnny. She’s too young to perform every day.’

‘She was born and bred in the circus, woman. Of course she’s old enough!’

Clever Quong Tart and the New Gold Mountain

Canton, China, 1859

Quong Tart and Quong Yen sat in the garden under the shade of a spreading mulberry tree. They gazed out over the tiled roofs to the terraced tea plantations where buffaloes pulled ploughs through fertile fields. Beyond lay a ring of mountain ranges.

Quong Yen licked the purple mulberry juice off his fingers. ‘Did you hear our honourable father talking about the New Gold Mountain?’ he asked.

Quong Tart shook his head. His long hair was pulled into a plaited queue that snaked back and forth across his back.

‘A miner who had just returned told him that gold nuggets lie on the ground, ready for the taking. It sounds like a fairy tale to me.’

Quong Tart’s eyes were round with wonder. ‘How did he get to the other side of the world? Did he dig a great big hole in the ground?’

Quong Yen laughed at his little brother. ‘He journeyed to the Port of Canton and sailed across the heaving seas in a smoke-belching ship. It’s a long way, especially for someone as small as you.’

Quong Tart grinned at his brother. ‘One day I’ll be as tall as a giant barbarian from those lands down under. My hair will be red and my nose will be long. And I’ll eat boys like you for dinner!’

‘In your dreams,’ scoffed Quong Yen. He stood up and smoothed down his blue cotton tunic. ‘Come, little brother, the scholars are waiting. We have lessons to attend.’

That evening, the boys’ favourite uncle joined the family for dinner. They sat on bamboo chairs around a carved wooden table, their blue and white bowls full of aromatic food, their chopsticks clicking.

The room was a riot of decorative objects—ivory carvings, lacquered boxes, stoneware jars and jade ornaments. Brightly painted fans and brushwork scrolls hung upon the walls, and a carved wooden screen in front of the window kept the evening breeze from cooling their food. Quong Tart’s father, Mei Quong, was a merchant, and their house showcased his beautiful wares.

After dinner, Uncle bowed to Quong Tart’s father and made an announcement. ‘I leave soon for the goldfields of Australia. I’m taking over fifty labourers with me who wish to try their luck. I need a scribe to deal with my paperwork and to write letters home for my men, many of whom are peasants who cannot read or write. My scribe must be a quick learner, able to pick up the uncouth language of the barbarians and become my interpreter. I understand that young Quong Tart is a good student fascinated by foreign places. I request your permission to take him with me.’

Quong Tart’s mother clasped her hands to her chest. ‘But Little Quong is only nine. How will he cope in a land full of man-eating monsters?’

Quong Tart held his breath. Under the harsh regime of the Dragon Throne, he knew that when he grew up he’d be a provincial merchant like his father. But Quong Tart wanted more—he wanted to see the world.

Mei Quong ran his fingers over his impressive moustaches and gazed at his young son. Quong Tart was small for his age, but well formed. He had a handsome face and intelligent eyes. They had named him Quong Tart—Bright Prosperity—in the hope he would live up to his name.

‘The scholars tell me, my son, that you are already reading the works of the great philosopher, Confucius. So your uncle’s words ring true. You have a quick mind and a good ear, and no doubt you could ably assist him in his endeavours.’

Quong Tart sat very still, head bowed, as he listened to his father’s words. Would he let him go?

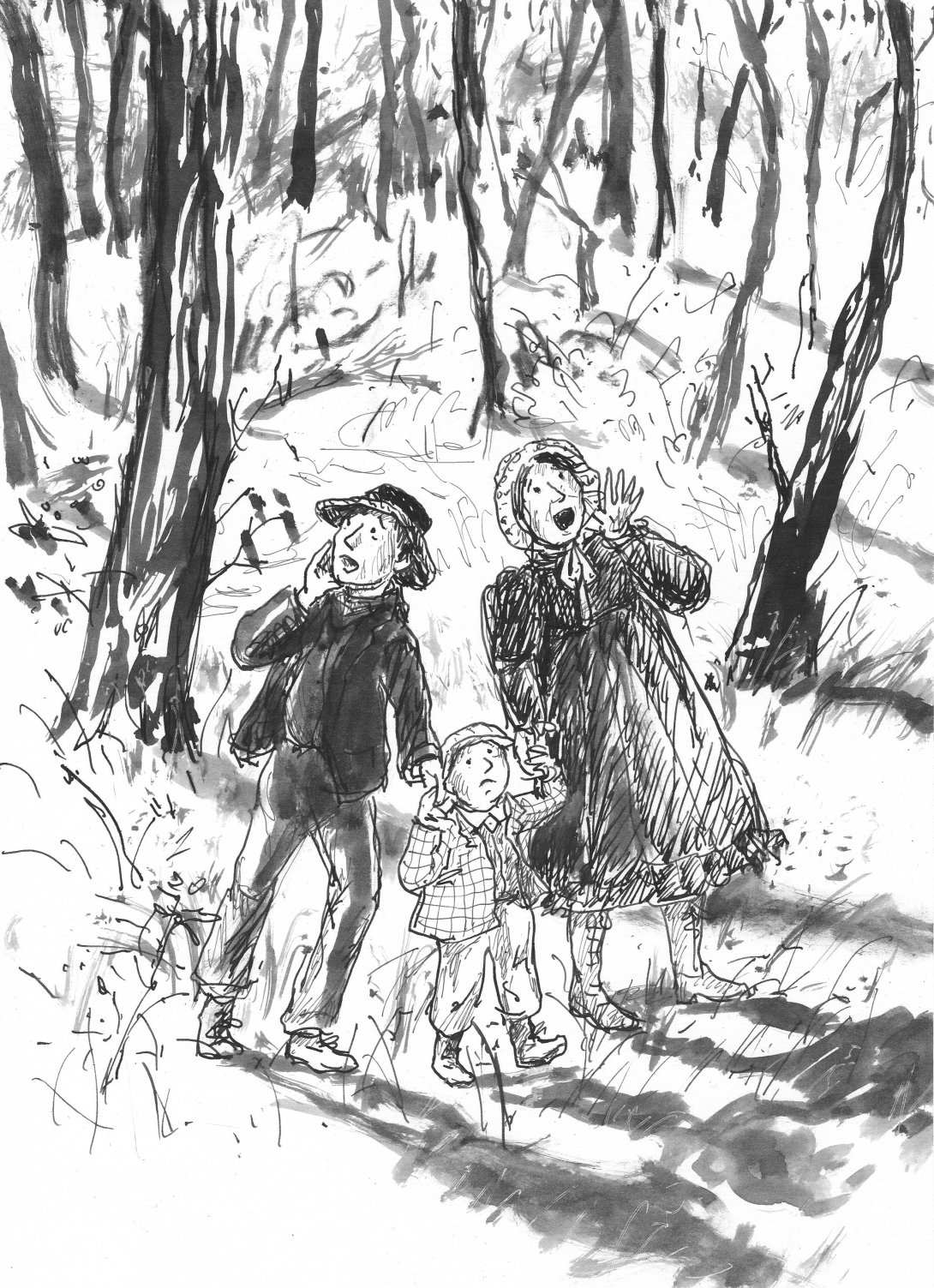

Valiant Jane and the Disappearing Trail

Wimmera District, Vic. (Wotjobaluk, Jaadwa, Jadawadjali, Wergaia and Jupagulk Country), Friday 12 August 1864

Jane slipped out of the bed she shared with her two brothers.

‘I’m hungry,’ Frankie mumbled in his sleep.

Jane smiled and tucked the quilt in around her little brother. She put on her dress and tied a white pinafore over the top of it. Magpies warbled their morning song as she tiptoed over to the fireplace in their one-room slab hut.

Jane’s mother, Hannah Duff, was stoking the fire. ‘Morning, poppet. Breakfast won’t be long. Fetch some water, please.’

Jane headed out the door, collecting the heavy bucket on the way. The seven-year-old struggled to carry it, even empty. She coughed as the cold air of the late winter morning hit her lungs. After ladling water from the barrel, she wrestled the tin bucket back inside. Water sloshed over her boots and made puddles on the dirt floor.

Damper was baking in the camp oven. Jane stuck her nose over the heavy iron pot sitting on the flames and inhaled the mouth-watering smell. Mutton chops sizzled on a griddle nearby. She screwed up her nose—more tough meat from the old sheep her father had killed last week.

Jane wished they could have something tastier, like the scrumptious parrot pie they’d had for her birthday. But then she remembered how sad she’d felt as she helped her mother pluck the delicate birds’ brilliantly coloured feathers.

Jane set the table with tin plates and mugs, then walked to the back of the hut and peeled the patchwork quilt off her brothers. ‘Wake up, sleepy heads!’

Isaac, who was two years older than Jane, hated mornings. He grumbled as he struggled off the thin mattress on the floor and pulled on his clothes. He walked out the door, dunked his head in the water barrel, and emerged a little less grumpy.

Frankie was nearly four, but Jane still helped him to get dressed, wriggling him into his pantaloons and tugging his smock down firmly over his head. Frankie wasn’t old enough to wear short pants, but he didn’t care. He was his usual bright, cheeky self, babbling away about the monsters that lived in the mallee-tree forest that surrounded their hut.

Their father, John Duff, sat at the head of the table and said a quick prayer before the family ate. After breakfast, he set off on his horse for Spring Hill Station, where he worked as a carpenter and a shepherd.

While Jane helped their mother clear the table, the boys rolled the mattress up against the wall, making a game of it.

‘We’ve caught the Mallee Monster! Don’t let him escape!’ Frankie yelled, struggling to keep his footing as the mattress got away from him.

‘Come on, you two,’ their mother said. ‘There are more chores to do. My old broom is worn out. I need fresh twigs from the heath in the forest to make a new one. You know the bushes I mean. Off you go.’

‘Please, Ma, can Jane come too?’ Isaac begged. It was nearly spring and the wildflowers were starting to bloom. ‘I want to show her the paper daisies near the broombush scrub.’

‘All right, you can all go, but take your hats.’ She sent them on their way with treacle sandwiches wrapped in a calico cloth and a stern warning to be back before dark.

‘We’ll be here in time for tea, Ma,’ Jane promised solemnly.

These are extracts from the seven stories in Courageous Kids and Their Amazing Adventures.