Sport is a storytelling machine. And for Australians that machine is prolific. Our popular imagination is crowded with stories drawn from sporting contests. Whether it is Ash Barty winning the Australian Open in 2022, Cathy Freeman running for Gold at the Sydney Olympics in 2000 or the ‘bodyline series’ of 1932–33, there are almost too many stories to tell. These stories, and many more, are explored in the National Library's exhibition Grit & Gold: Tales from a Sporting Nation.

More than a Medal

Some of these stories go beyond simply providing a memorable anecdote to creating a moment which changed the way Australia saw itself. Cathy Freeman’s victory in the 400-metre race at the Sydney Olympics is one such moment. Freeman was already famous for having carried both the Aboriginal and Australian flags after her victory in the 200-metre final of the 1994 Commonwealth Games. Carrying both flags reflected her pride in being Indigenous and in being Australian. For many Australians this celebration of her victory symbolised the possibility of reconciliation between First Australians and European Australians. At the Sydney 2000 Olympics Freeman was selected to light the Olympic Cauldron at the beginning of the games. The image of her standing with an Olympic torch surrounded by fire became a symbol of a new Australian identity that recognised the centrality of First Australian people to the Australian story. All that remained for this story to become part of the national imagination was for her to run a winning race. Commentator Bruce McAvaney exalted in Freeman’s convincing victory, ‘What a legend … what a champion!’ Co-commentator and Australian sprint legend Raelene Boyle said what many Australians felt: ‘What a relief!’

The hero's journey

What is it about sport that makes it so good at generating stories? Sporting contests provide a space for compelling narratives to be created. The constraints and rules of each contest, and the passion of the participants, allow the audience to identify with the athlete and care about the outcome. The possibility of victory or defeat means that there is something at stake in each contest. And the physical danger inherent in many sports amplifies this sense of jeopardy. The emotions and pain expressed on players’ faces provides a very raw and powerful experience for fans. As each sporting contest unfolds, there is the possibility for heroes to appear, to overcome obstacles and to return home victorious. Similarly, villains on the opposing side can thwart the hopes of a team and its fans. Following the contest is an immersive experience in which the rest of the world disappears. There is suspense and surprise, there is exaltation and despair. You are taken on a journey which has a definite end, even though you might not always like the result.

These sporting stories can escape their code of origin and come to symbolise much more than a fleeting moment on a sporting field. They can be inscribed with a broader meaning for the individual, neighbourhood or nation. They can come to be part of a shared set of experiences that bind a community together. For example, Aussies love to boast that they ‘punch above their weight’ in international sporting competitions. Whether it is dominating in cricket (sometimes), winning gold at the Olympics (most of the time) or exceeding expectations at the Football World Cup (passionately hoped for), the triumph of Australian athletes is seen as proof positive of Australia’s success as a nation.

Being a good sport

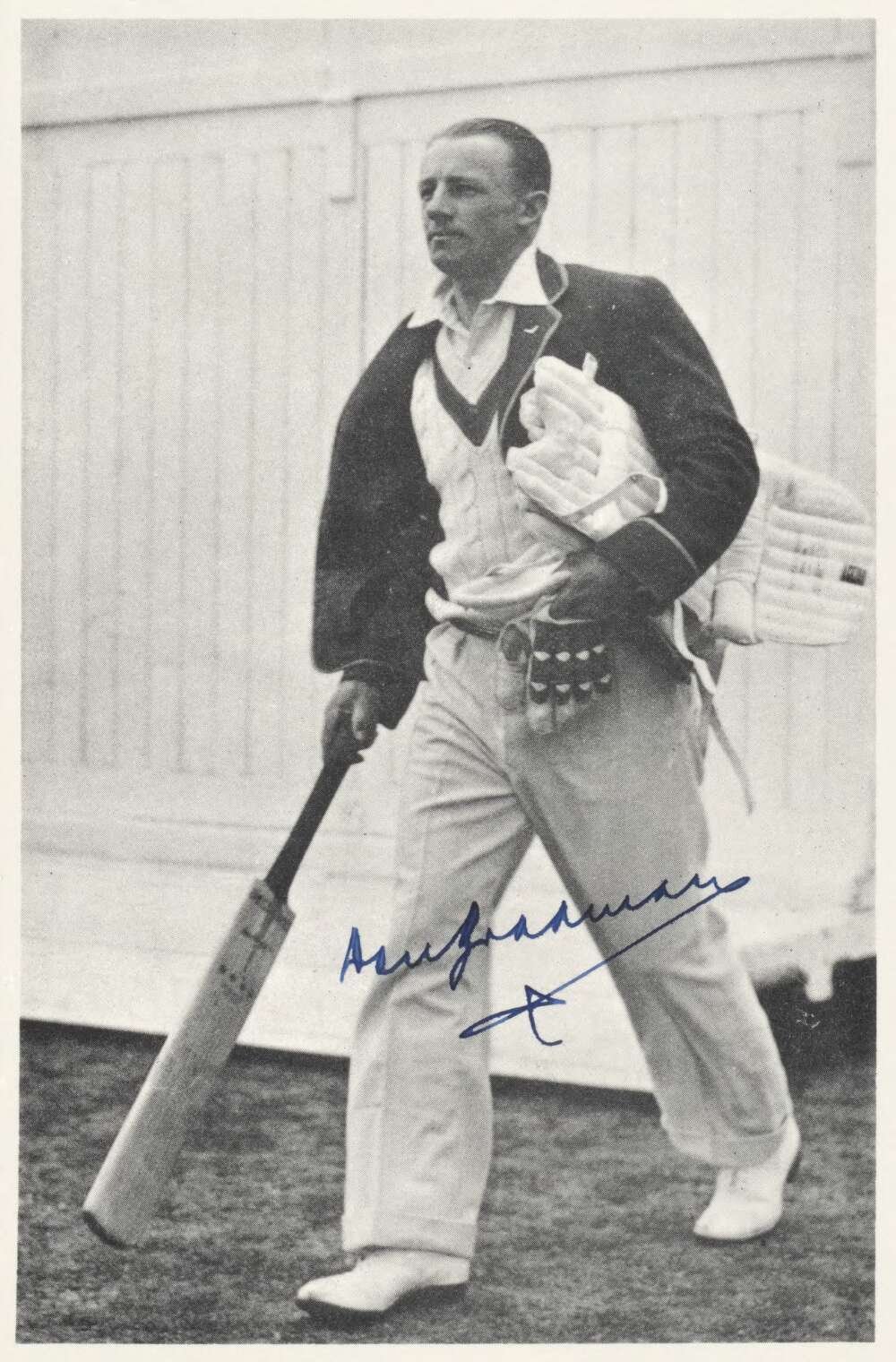

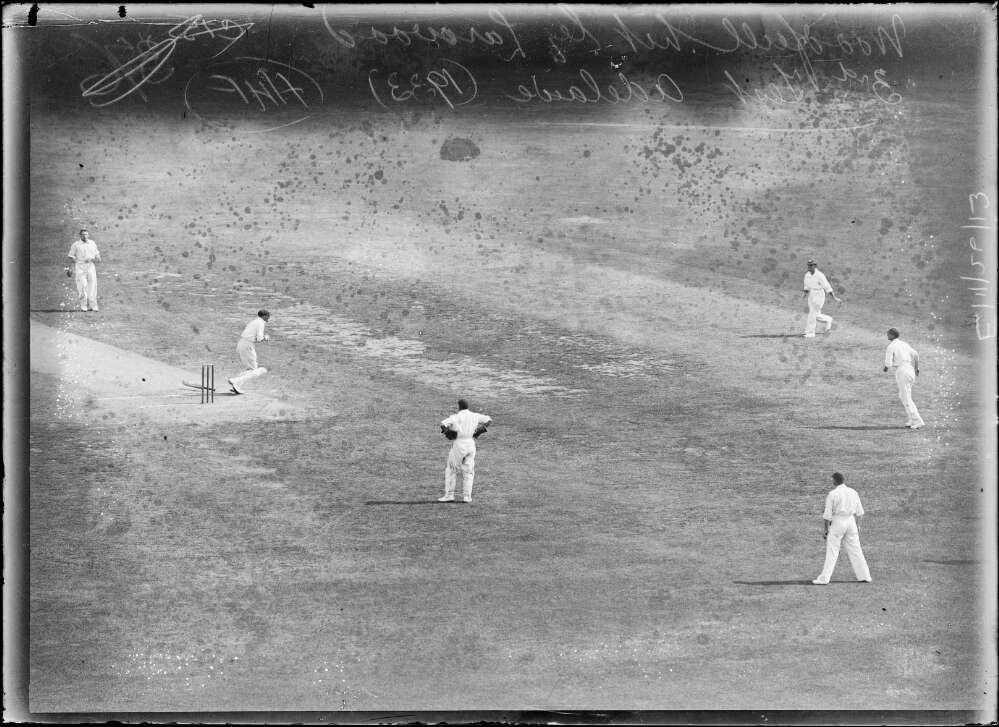

The bitter controversy that surrounded the ‘bodyline series’ in 1932–33 is the perfect example of how sporting moments can be absorbed into Australia’s national mythology. ‘bodyline’ is the term used to describe the tactics used by the English cricket team to subdue Australia’s batting line-up, and in particular its all-time batting hero, Don Bradman. It involved targeting the leg stump with intimidating fast-rising deliveries. The batter had to quickly choose whether to duck, to allow the ball to hit their body or to strike it with their bat. Additional fielders were placed on the leg side to catch the ball should the hapless batter try to play a shot. While the strategy did restrict the flow of runs, it was condemned as unsporting by many players, journalists, and fans.

During the third test at the Adelaide Oval, English fast bowler Harold Larwood hit Australian captain Bill Woodfull on the chest with a rising delivery. The game was stopped while Woodfull recovered. The English captain, Douglas Jardine, was overheard as he loudly congratulated Larwood’s delivery. Spectators grew increasingly restless as the English persisted with their leg attack. Woodfull bravely continued his innings, but was hit again on the body, and eventually succumbed for just 22 runs. The next day, newspapers across Australia quoted Woodfull as saying, ‘There are two teams out there. One is trying to play cricket and the other is not’. In this story, Bradman and Woodfull are local heroes, standing bravely against an English bully.

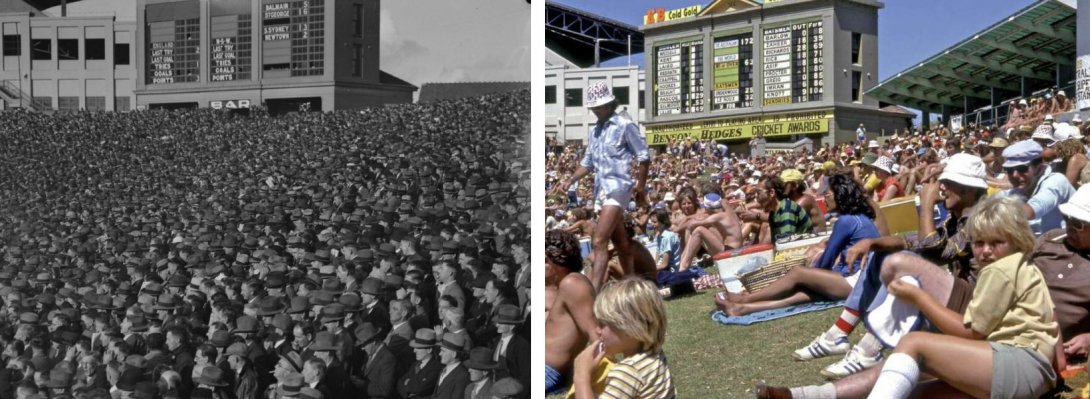

When looking at changes in sport over the last 200 years, you can see that it provides a window into Australian history. Whether it concerns the emergence of a distinct Australian national identity in the nineteenth century, the growth of professional sport in the twentieth century or the rise of elite women’s competitions more recently, sport gives us an invaluable insight into major changes in our society and culture.

Our collections are a place where these sporting stories can be found and retold for future generations. The books, magazines, paintings, drawings and photographs of past sporting contests provide a storehouse of memories for all Australians to cherish. Grit & Gold: Tales from a Sporting Nation shows you some of the stories you can find by visiting us.