In many countries around the world, the first day of January is an auspicious occasion. The start of the Gregorian calendar, it represents the rolling over of one year into another – marked by celebrations, resolutions and new beginnings.

For some, the first of January has another important connotation. It’s Public Domain Day – the day on which a new batch of copyright terms expire and creative works become available for public use. These works can be used freely – copied, published, adapted or incorporated into new works without permission from the original copyright holder.

Public domain around the world

Copyright law and associated terminology differs significantly from country to country. In the United States, copyright terms are determined based on how much time has elapsed since the work’s publication, and since the death of the creator or copyright holder. Notable works that enter the public domain in the U.S this year are A.A Milne’s Winnie the Pooh, Ernest Hemingway’s The Sun Also Rises, and the 13th edition of the Encyclopaedia Britannica.

In 2004, changes to Australian copyright law saw a similar “plus 70” rule enacted, whereby the free use of creative works is restricted until 70 years after the creator’s death. This made the Australian legislation comparable to that of the U.S and the European Union, with one notable difference. Prior to the change, Australia’s standard copyright term was 50 years. The change was not applied retroactively, meaning that works by Australian creators who died before 1955 are generally in the public domain. Works by Australian creators who died after 1955 will come out of copyright on 1 January 2026.

Unpublished literature and the Copyright Amendment Act

The following decade saw minimal changes to Australian copyright law, until the Australian Law Reform Commission published Copyright and the Digital Economy in 2013. The discussion paper explored contemporary copyright issues and their application in a digital context. One such issue was the matter of unpublished works, and their copyright in perpetuity status. This rule meant that documents of historical significance, including correspondence, records and other communications, would never be available for public use. An historic amendment to Australia’s copyright law in 2017 addressed this issue, amongst others, and the copyright in perpetuity status of unpublished materials was removed.

This change brought some interesting new materials into public domain, many of which are held in the National Library’s collections, including:

-

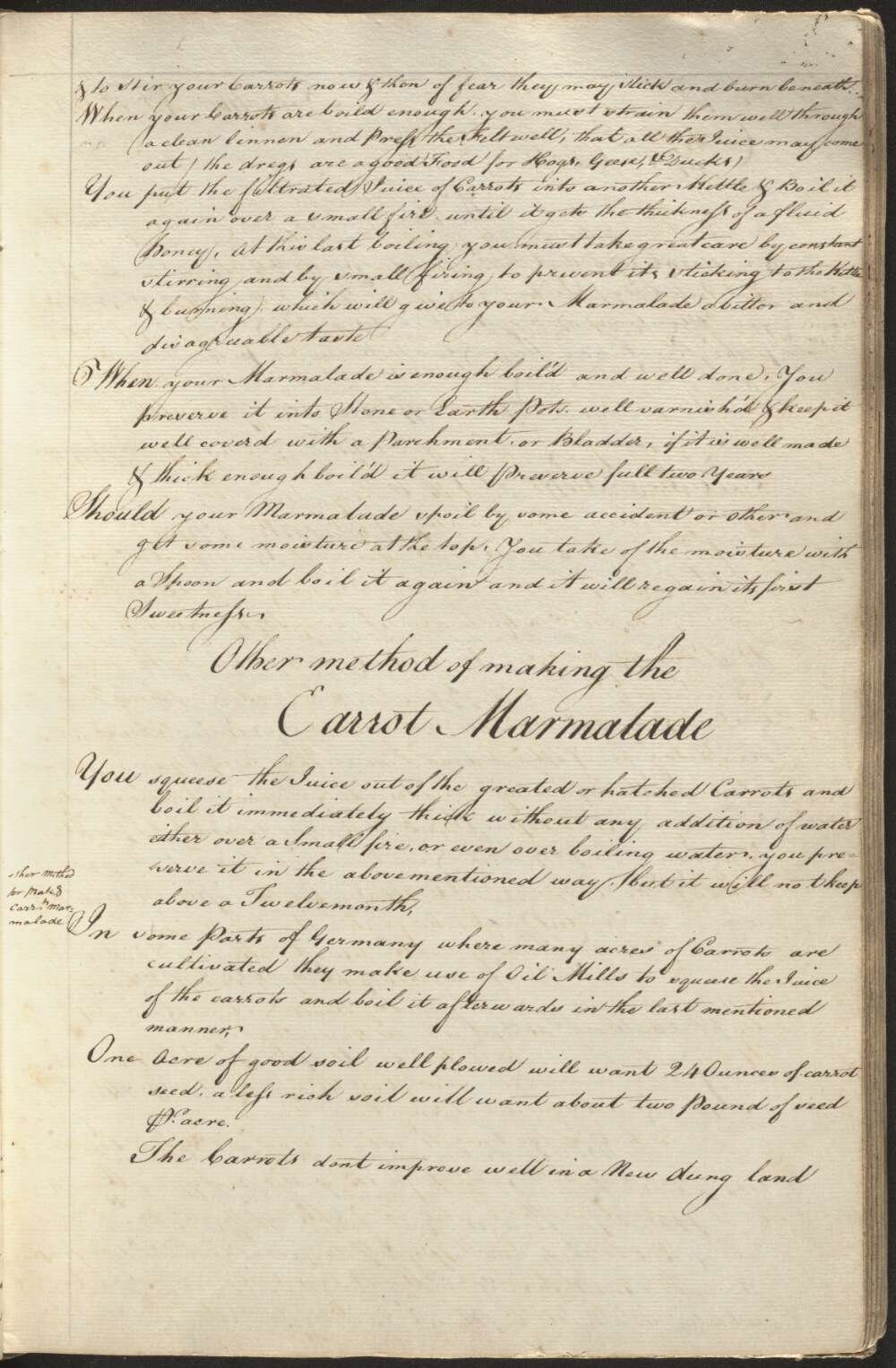

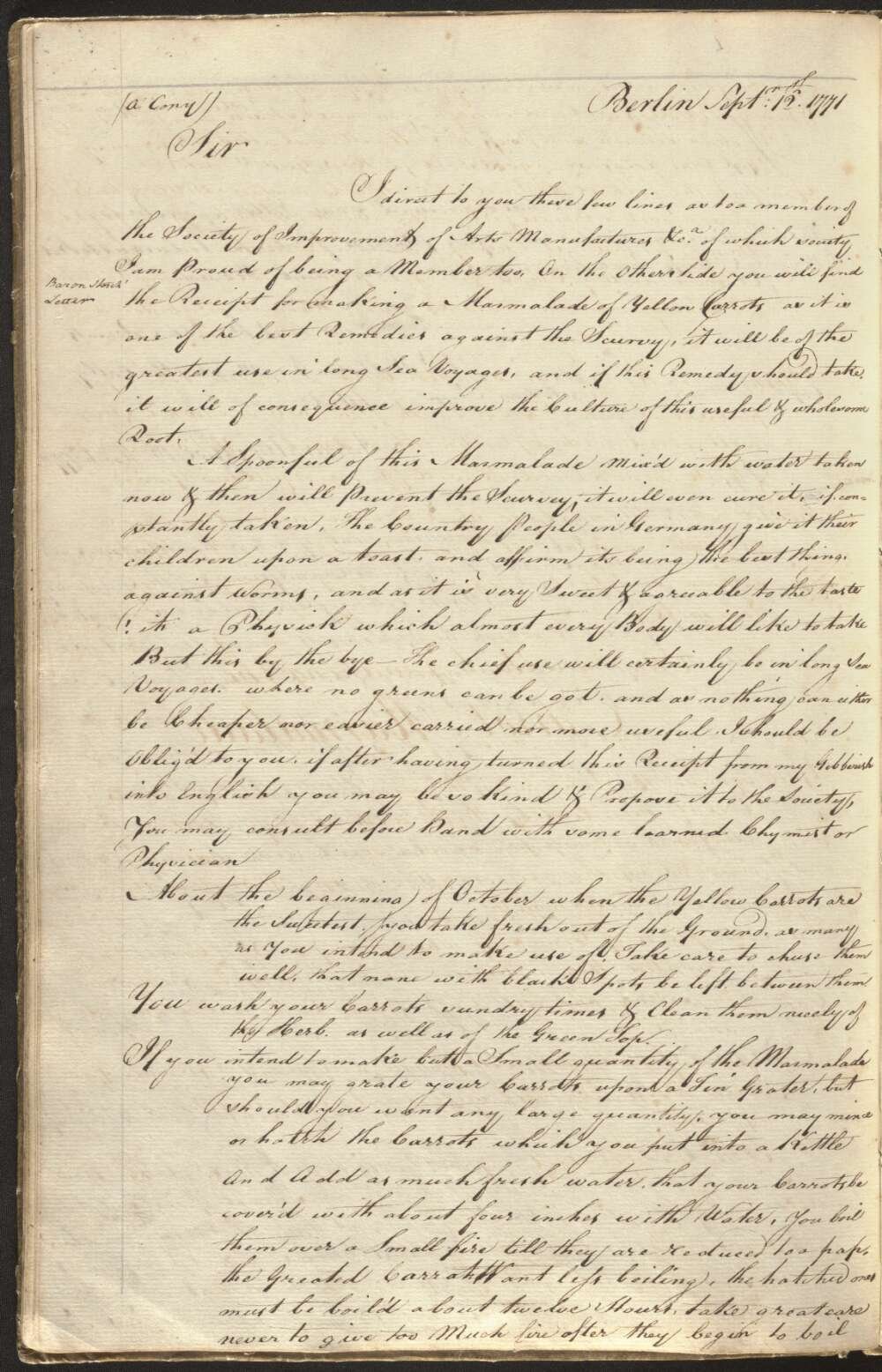

The correspondence of Captain Cook, including a 1771 letter from Baron Storsch advocating the wonders of carrot marmalade as an effective treatment for scurvy

-

A letter from Jane Austen to her sister Cassandra, where she discusses ongoing work on Pride and Prejudice, under its original title, First Impressions

-

A suite of correspondence by Charles Darwin, Henry Lawson, Banjo Paterson and Dame Nellie Melba

To 2026 and beyond

For Australians, our next big date for public domain works is January 1, 2026. Works entering the public domain will include the publications of Australian authors who died in 1955, and photographs taken in or since 1955.

It’s not all quiet on the public domain front until then, however - the rules around unpublished works, orphan works (i.e. works with no known author), and grey literature (including government publications) means that each year still brings us fresh delights in the form of public domain material. In 2022, several works from the Library’s collections came into public domain on January 1. You can find out more about them in this handy roundup of new public domain works at the National Library.

And while you wait to see what treasures await us on January 1, 2023, you may pass the time by exploring the Library’s useful resources on copyright, or turning your hand to a fresh batch of carrot marmalade, courtesy of Captain Cook.

Captain Cook’s carrot marmalade, as written by Baron Storsch in 1771

“About the beginning of October when the yellow carrots are the sweetest, you take fresh out of the ground as many as you intend to make use of. Take care to choose them well, that none with black spots be left between them.

[...]

If you intend to make but a small quantity of the marmalade you may grate your carrots upon a tin grater but should you want any large quantity, you may mince or hatch the carrots which you put into a kettle and add as much fresh water that your carrots be covered with about four inches."

"[...]

When your carrots are boiled enough, you must strain them well through a clean linen, and press the felt well, that all the juice may come out. The dregs are a good food for hogs, geese and ducks.

You put the filtrated juice of carrots into another kettle and boil it again over a small fire until it gets the thickness of a fluid honey, at this last boiling you must take great care by constant stirring and by small firing to prevent its sticking to the kettle and burning, which will give to your marmalade a bitter and disagreeable taste.

[...]

Should your marmalade spoil by some accident or other and get some moisture at the top, you take off the moisture with a spoon and boil it again and it will regain its first sweetness.”