That there is such an Art, as that of Swimming, and what is to be observed before one enters on putting the Precepts of it in Practice. – Melchisédech Thévenot

In 1764, a small book about swimming was published in London.

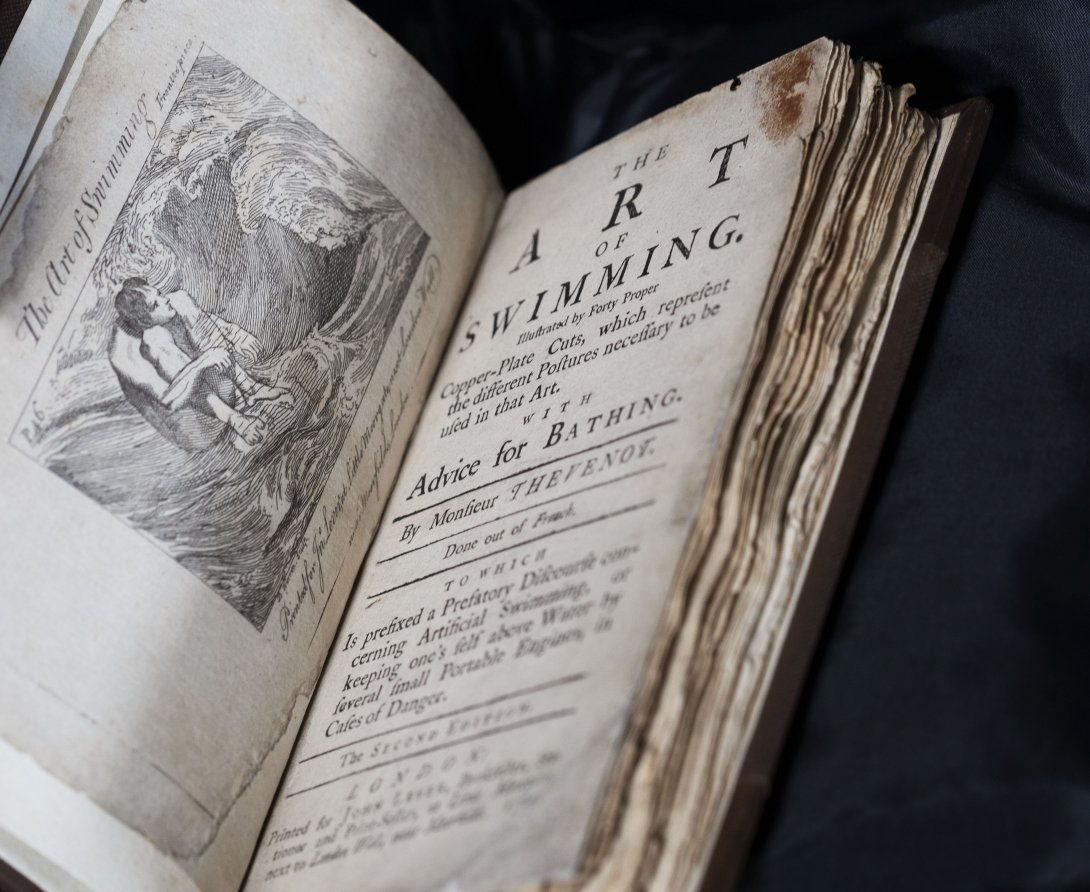

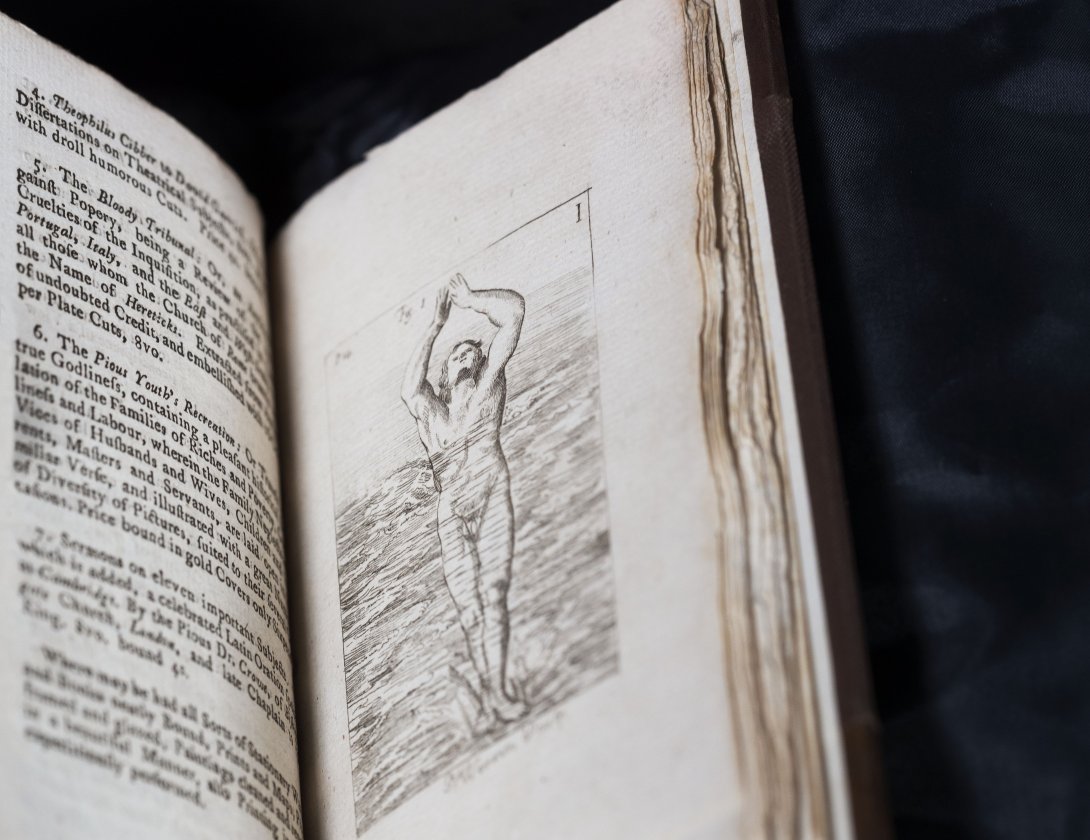

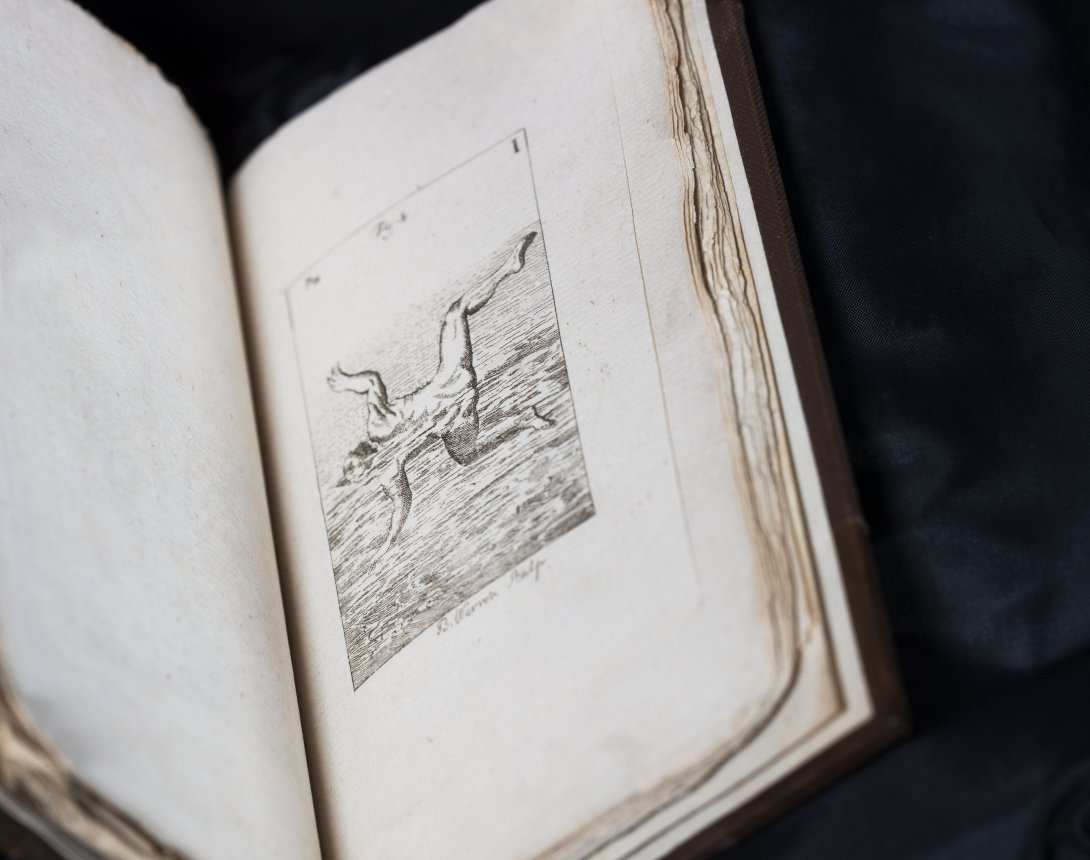

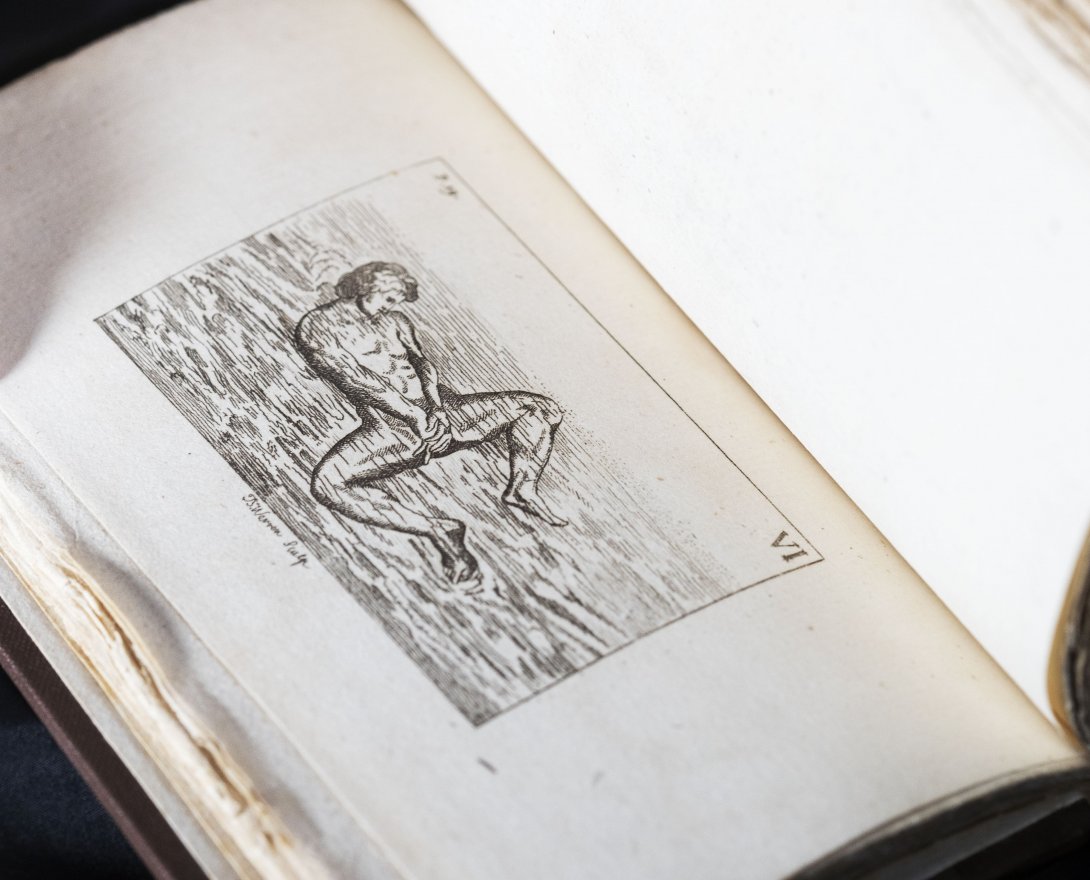

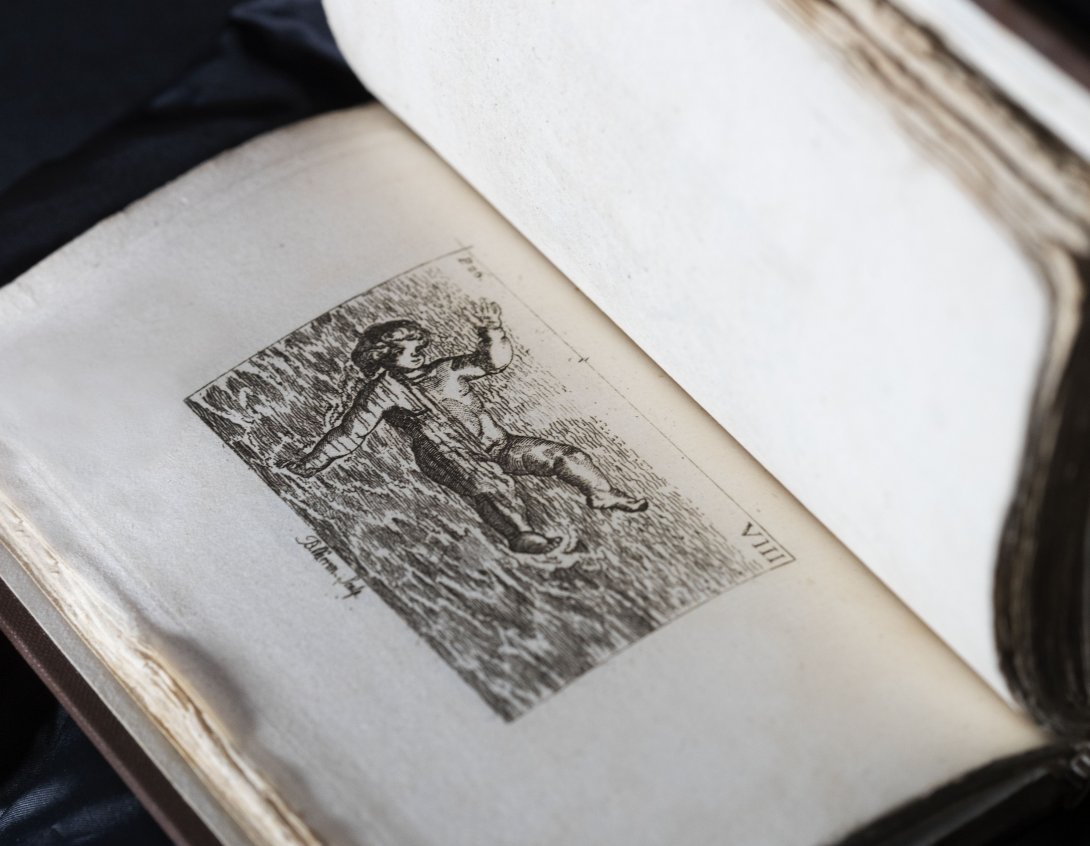

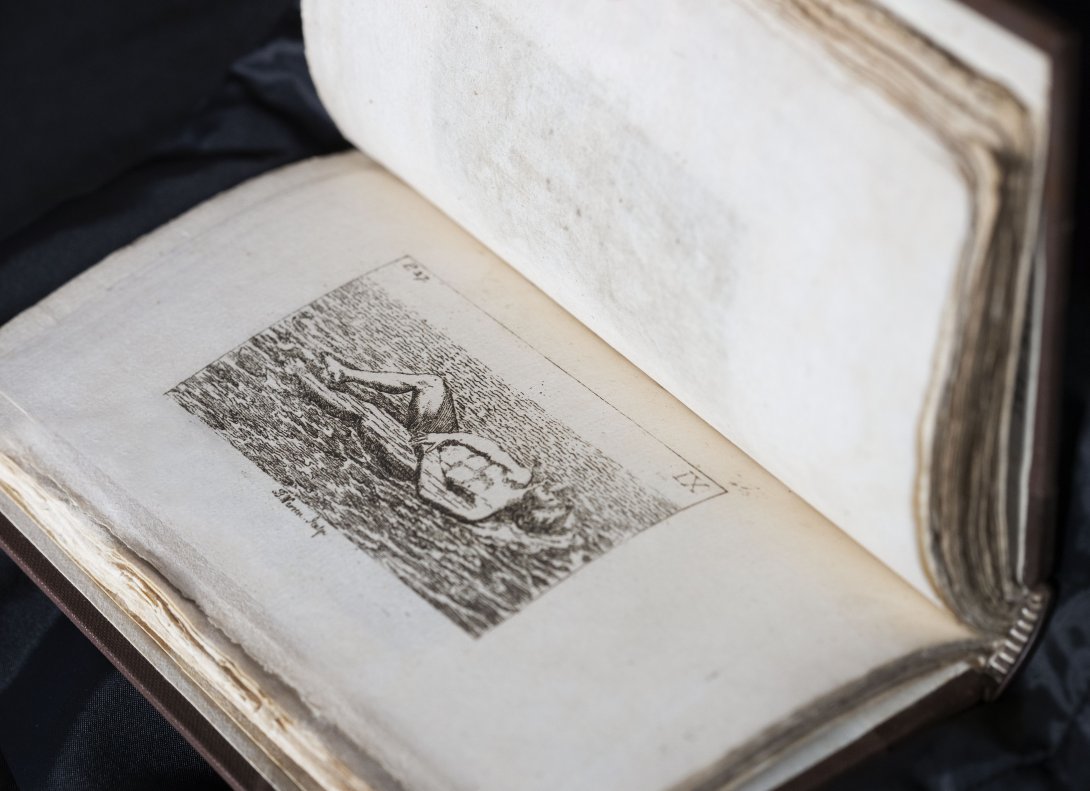

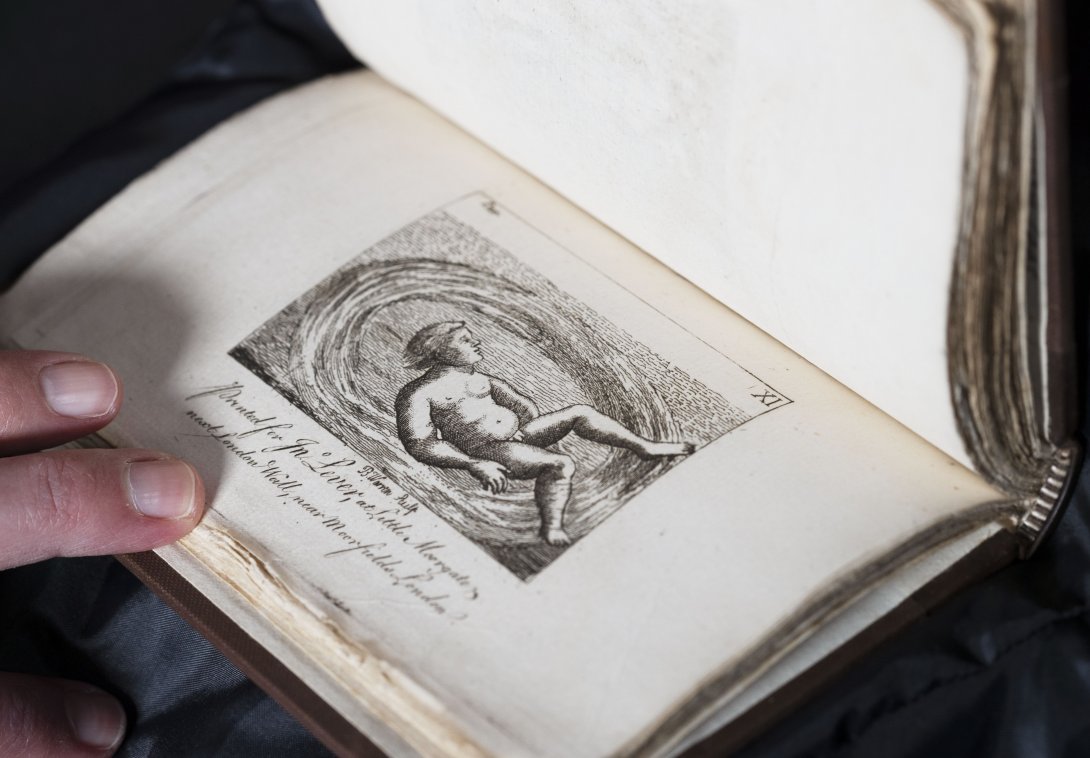

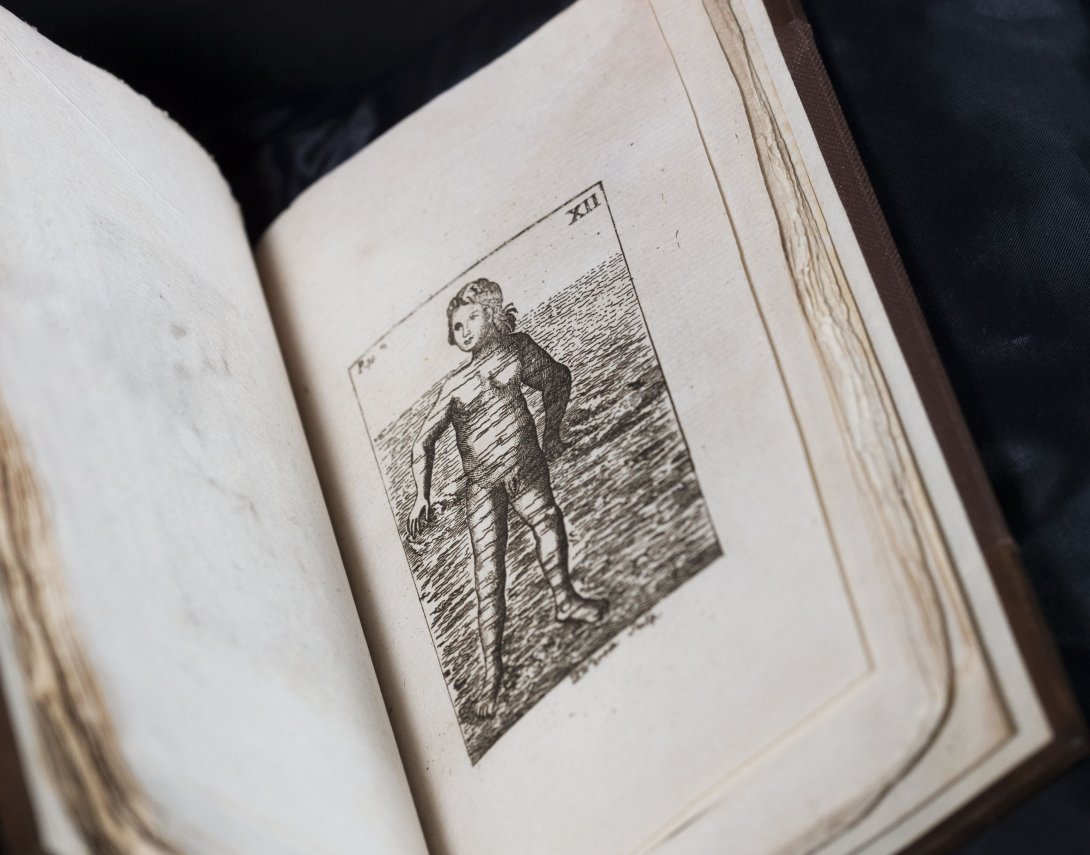

It lays out how to swim in thirty-eight rules or ‘precepts’. There are forty copperplate engravings – illustrations it calls 'proper', which 'represent the different postures necessary to be used in that Art.'

This blog, by the Library’s Rare Books and Music Curator Dr Susannah Helman, explores this charming little book, just in time for the last days of summer. It may even be helpful the next time you take the plunge!

The book has a long title:

THE ART OF SWIMMING. Illustrated by Forty Proper Copper-Plate Cuts, which represent the different Postures necessary to be used in that Art. With Advice for BATHING. By Monsieur THEVENOT. Done out of French. To which Is prefixed a Prefatory Discourse concerning Artificial Swimming, or keeping one’s self above Water by several small Portable Engines, in Cases of Danger. The SECOND EDITION. London: Printed for John Lever, Bookseller, Stationer and Print-Seller, at Little Moorgate, next to London Wall, near Moorfields, 1764.

It is an English translation of a French book, first published in 1696.

The first French edition’s title page has none of the waffle of our 1764 English version: L’Art de Nager, démontré par figures, avec des avis pour se baigner utilement. Par M. Thevenot [The art of swimming, demonstrated by figures, with advice for bathing usefully], A Paris, Chez Thomas Moette, ruë de la Bouclerie MDC XCVI Avec Privilege du Roy.

The Bibliothèque nationale de France in Paris has fully digitised their 1696 first edition.

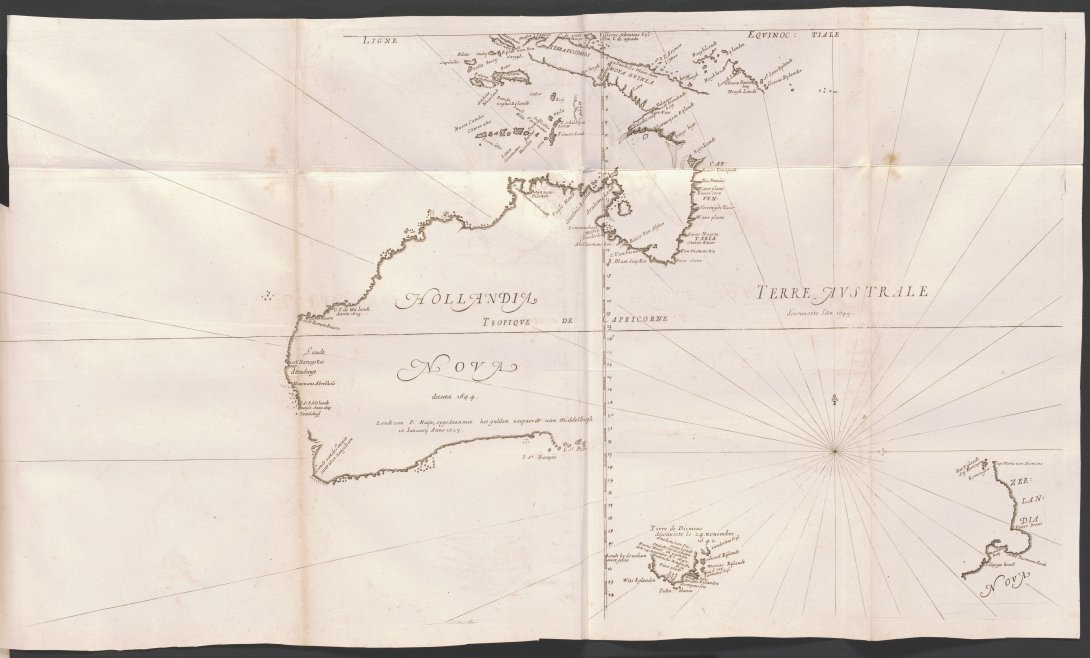

The original French author was Melchisédech Thévenot (1620–1692), traveller, diplomat and writer, and librarian to French King Louis XIV from 1684 to 1692. Thévenot is best known to students of Australian history for his popular travel book – Rélations de divers voyages curieux (Account of diverse curious voyages), which contains a landmark early European map of Australia. The book brought together information about recent voyages of exploration.

The National Library of Australia holds a first edition (1663) of the first volume of Thévenot’s travel book and numerous states of the map of Australia and New Zealand as single sheet maps. The Library also holds the 1696 final, complete edition of the work – fully digitised and available through our catalogue.

This map is important as it brought recent Dutch mapping of Australia and New Zealand to a very wide audience. On his two voyages to these parts in the 1640s, Abel Tasman mapped the southern coast of Australia, parts of Tasmania and part of New Zealand. It is the map you can see on the Library’s wall map Archipelagus Orientalis, sive Asiaticus (1663) by Joan Blaeu – it was printed in the same year as Thévenot’s map. This was the mapping of Australia and New Zealand Europeans knew until James Cook charted Australia’s east coast and New Zealand in 1769–1770, and Matthew Flinders charted Bass Strait several decades later.

The 1696 edition of Thévenot’s Rélations divers was published and illustrated, respectively, by the French father and son, Thomas and Charles Moette. They also published the first French edition of Thévenot’s swimming book that year. It was a busy year for them.

In his introduction, Thévenot claims that his is the first French book about swimming, which indeed it was. He acknowledges he has drawn on others' work, including English writer Everard Digby.

An English translation of Thévenot was published in 1699, with similar plates to the 1696 French edition. The Library’s 1764 English edition is practically the 1699 translation, reset.

The text is difficult to summarise – little of the translation is pithy – but it argues that swimming is an important skill and deserves to be studied and systematised. Thévenot argues that:

at length an Art is form’d, reducible to certain Rules, such as you’ll find in this little Tract, and which being put in practice by frequent Use and Experience, one may attain to the habit of Swimming perfectly. …

Its end is far more noble, and the consequences of it so very considerable, that none ought to be ignorant of it, especially since Life it self is concerned in it, and the Preservation of it, from those Dangers to which those are liable who cannot Swim. …

There is no Season wherein a man may not have occasion to practice the Art of Swimming; but any Season is not proper to learn it in.

Much of the advice is sensible:

Before you go into the water, you ought to see that it be clear, that there be no scum or froth on the surface, what sort of bottom it has, that there be no weeds or mud, for ones feet may be entangled among the weeds, or one may sink into the mud, and the water coming over ones head, remain there, and be drowned.

American Founding Father Benjamin Franklin (1705–1790) found Thévenot’s book very useful. He had a copy of the 1699 English translation. In his Autobiography, he writes:

I had from a Child been ever delighted with this Exercise, had studied and practis’d all Thevenot’s Motions and Positions, added some of my own, aiming at the graceful and easy, as well as the Useful.

On a visit to London in 1725–6, Franklin demonstrated his swimming in the Thames to his companions:

All these I took this Occasion of exhibiting to the Company, and was much flatter’d by their Admiration.

The 1764 edition’s plates have been re-engraved by Bartholomew Warren, who worked for the publisher John Lever. He was a young man at the time, likely fresh from his apprenticeship under William Tringham Senior, which he commenced in 1757. Apprenticeships usually lasted for 7 years.

Warren’s plates are clearly copies of Charles Moette’s if not the 1699 edition.

Few other examples of Warren’s work are easy to find. One of his engravings, a cartoon, complete with speech bubbles, originally a frontispiece to a book, survives at the London Metropolitan Archives. Behind two figures suffering from consumption, it depicts the bookshop of John Lever, the printer of the 1764 edition. John Lever and Warren were busy in 1764, also publishing a third edition of Low-life: or One half of the world knows not how the other half live. Warren engraved the frontispiece.

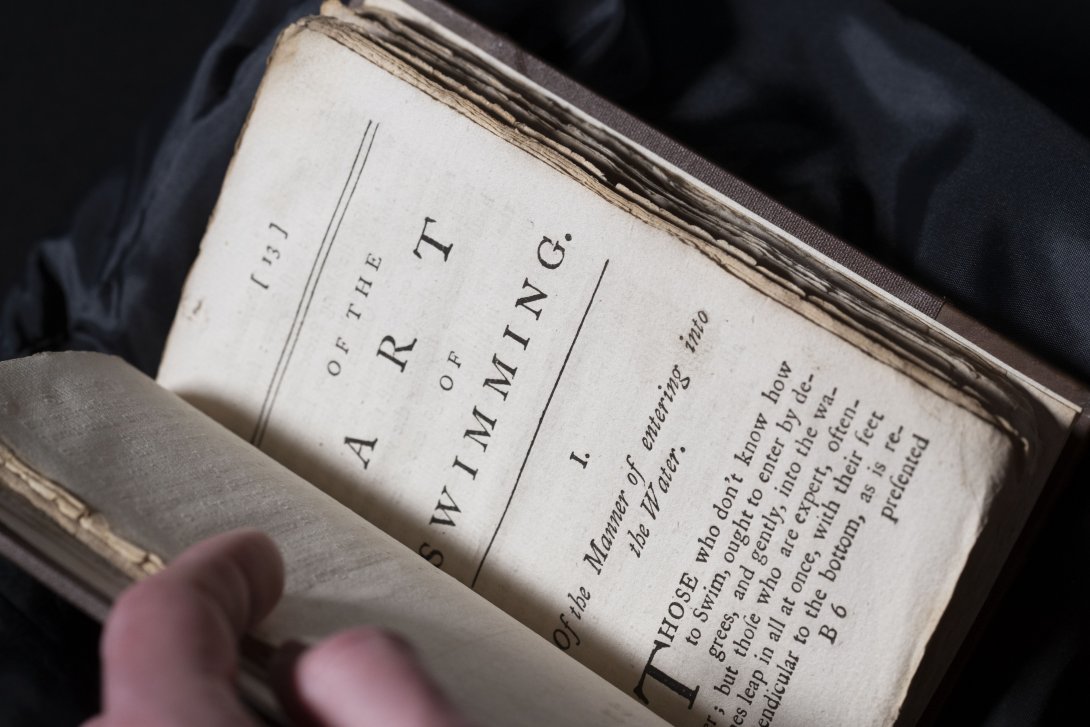

Now to a selection of the engravings, and the rules that accompany them:

Those who don’t know how to Swim, ought to enter by degrees, and gently, into the water; but those who are expert, oftentimes leap in all at once, with their feet perpendicular to the bottom, as is represented in the first figure

It continues:

sometimes after having walked a little way in the water, they lie along stretching out the body and arms, as you may see in the second figure

To turn easily you must incline your head and body to the side you would turn to, and at the same time move and turn your legs after the same manner, as you would do to turn the same way on land, this hinders and stops the motion of your body forwards all at once.

This way seems difficult, though it imitates that posture they say is natural to Man, to look upwards; and if we knew how to make use of it, there would not be so many drowned as there daily are; … But to learn to Swim on your back, observe what follows.

When you are upright in the water, lie down on your back very gently, elevate your breast above the surface of the water, and in the mean while keep your body always extended in the same right line, your hands lying on your belly, striking out and drawing in your legs successively, and keeping them within two feet of the surface of the water, and govern yourself according to figure 8.

There is another way of turning from the right to the left, and contrariwise, as a globe does about its axis. If you Swim on your belly, and would turn to the left, you must extend your right hand and arm as far out before you as you can, and turn your face, breast, and whole body, to the left lifting up your right hand towards the top of the water, and you’ll find yourself on your back, and from your back you may turn again on your belly, and so as often as you please.

Although there is not much occasion for any great motion of the hands for those that Swim on their backs; yet if you design to make any great advances forward, you must use both your feet and hands too. This way is chiefly useful for Swimming against waves, and carries swifter than Swimming on the belly.

We go backwards, when lying on the back we push ourselves onward with our feet and legs; but to do the contrary, and advance forward we must, lying always on the back keep the body extended at full length in a strait line, the breast inflated, so that that part of the back which is between the shoulders must be concave (or hollow) and sunk down in the water, the hands on the belly. … This way is not only very pleasant, but also when you find yourself weary sometimes with Swimming, and far distant from the shore, it may be useful to rest yourself, and give you time to recruit your Spirits.

The Circle (or entire Compass) is made, when one foot remaining immoveable, the other turns round, and describes a Circle, ending where it began: In the same manner the head may remain immoveable, while the legs strike the water, and make the body turn round. To perform this, the body, lying on the back, if you would begin to turn from the right to the left, you must first sink your left side somewhat more towards the bottom than the other, and lift out of the water your legs successively…

Being in the Water in a posture upright, you may turn and view every thing successively round about you. You may see that I am indeed upright, but to make you understand those motions of my feet which you cannot see; suppose I have a mind to turn to the right, in the first place I do, as it were, embrace the Water with the sole of my right foot, and afterwards with that of my left, and in the mean while I incline my body towards the left; I also draw as much as I can the Water towards me with my hands, and afterwards drive it off again … This manner of swimming may be very useful; it is very serviceable to know what happens on every side.

Another copy of this edition is available online. Our copy is slightly different – the plates are gathered at the back.

The National Library of Australia has many such rare yet practical books in its collection. Search our catalogue for more!

Dr Susannah Helman is the Rare Books and Music Curator at the National Library of Australia.