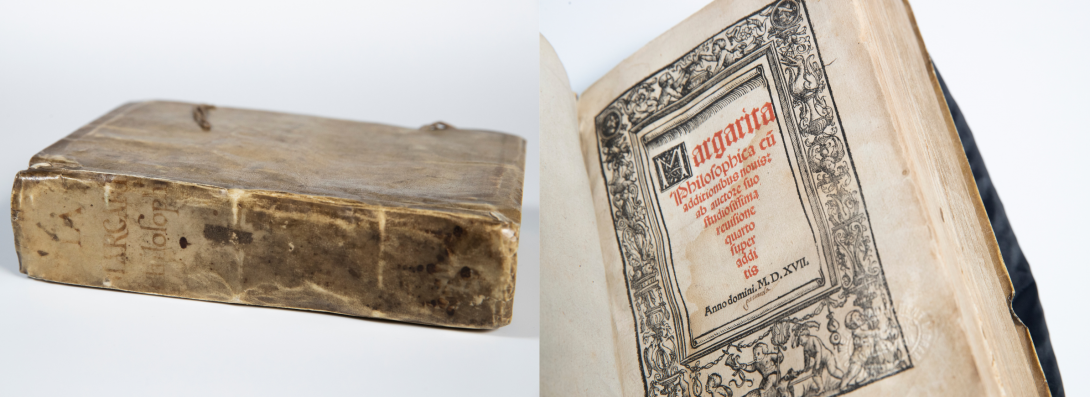

Sometimes you find a book that has it all—great age, fascinating illustrations, diagrams and maps, a wealth of information, and many marks of use.

I was looking for something else when I realised we held a book with all these things. It even has a woodcut of mythical creatures. It is the Margarita Philosophica (Pearl of Philosophy) (1517) of German Carthusian monk and prior Gregor Reisch (c. 1467—1525).

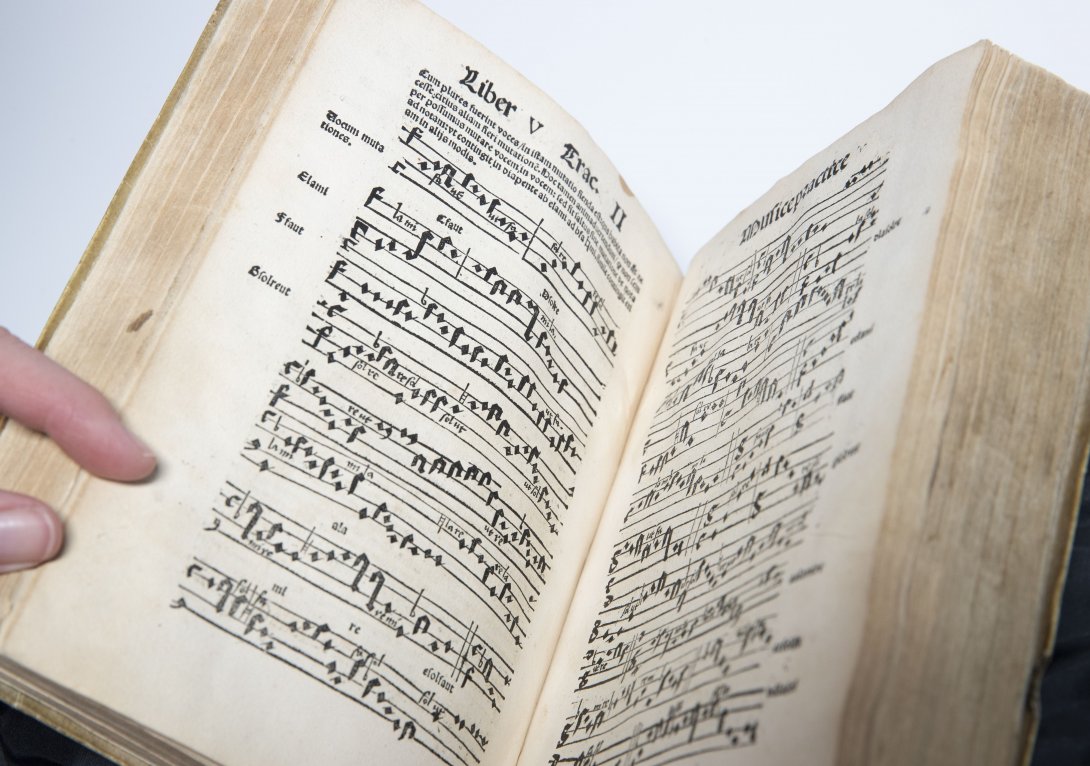

First published in Freiburg (in modern Germany) in 1503, the Library’s copy is the book’s fourth authorised edition. It was published in Basel (in modern Switzerland) 506 years ago—5 March 1517 to be exact. It is a compendium of knowledge, ancient and modern, Christian and secular, a textbook for students. In twelve parts—called books—it covers the range of university subjects students were required to master in the early modern period—grammar, dialectic, rhetoric, arithmetic, music, geometry, astronomy, natural philosophy, psychology, logic and ethics. Written in Latin, in the form of a dialogue between teacher and student, it is the world in a book.

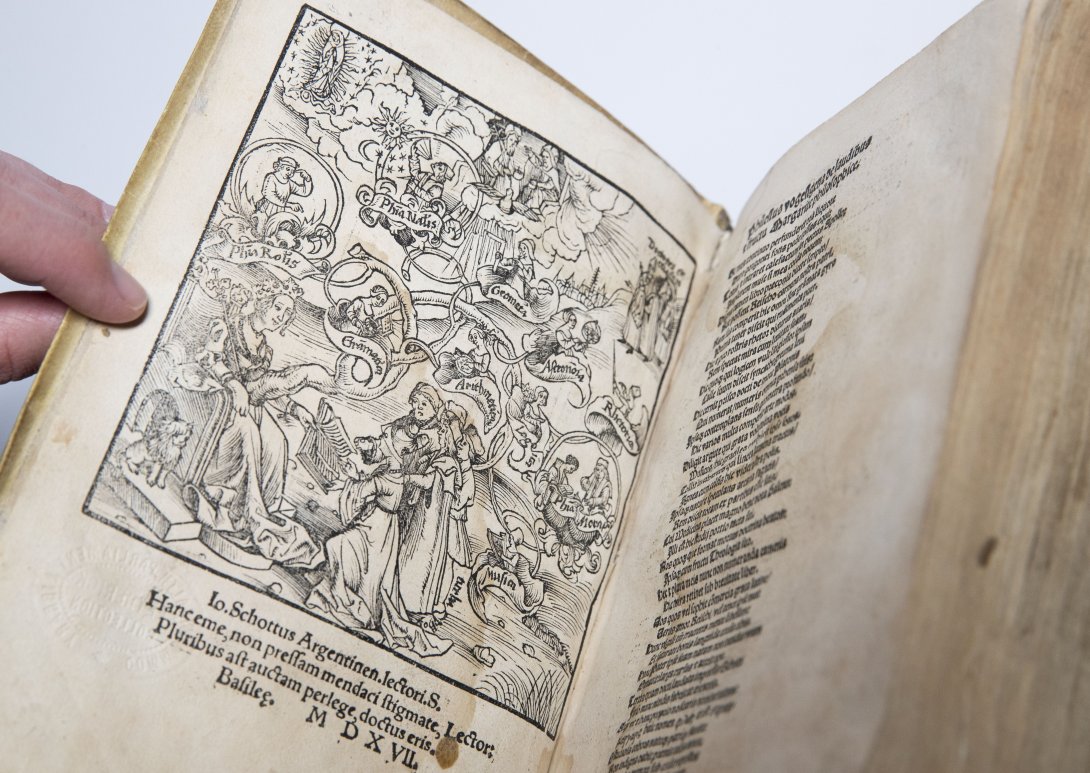

This woodcut, which first appeared in the 1508 edition, sums up the Margarita Philosophica. Wisdom, crowned, sits on a throne. A tree grows out of her abdomen. The book’s subjects are named and illustrated in the tree’s branches and leaves. In her left hand, she shows students and their teacher a book, which they are reading eagerly. A very small lion (or is it a poodle with a lion cut?) sits quietly beside her throne, closest to the reader.

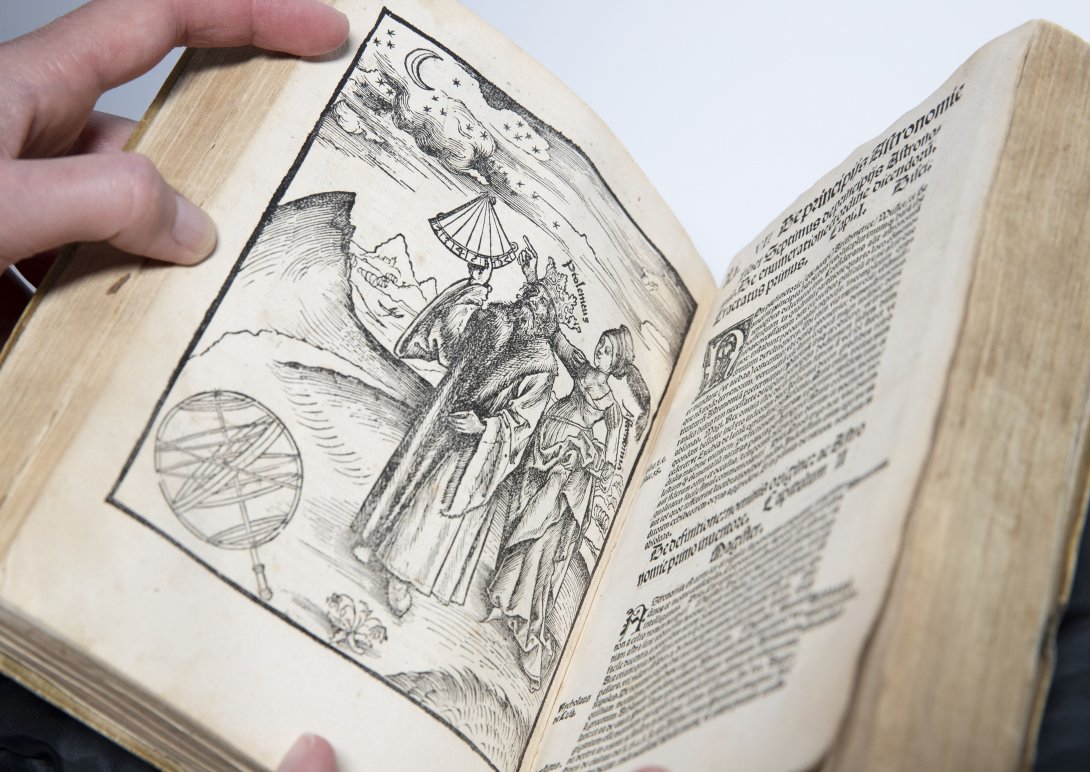

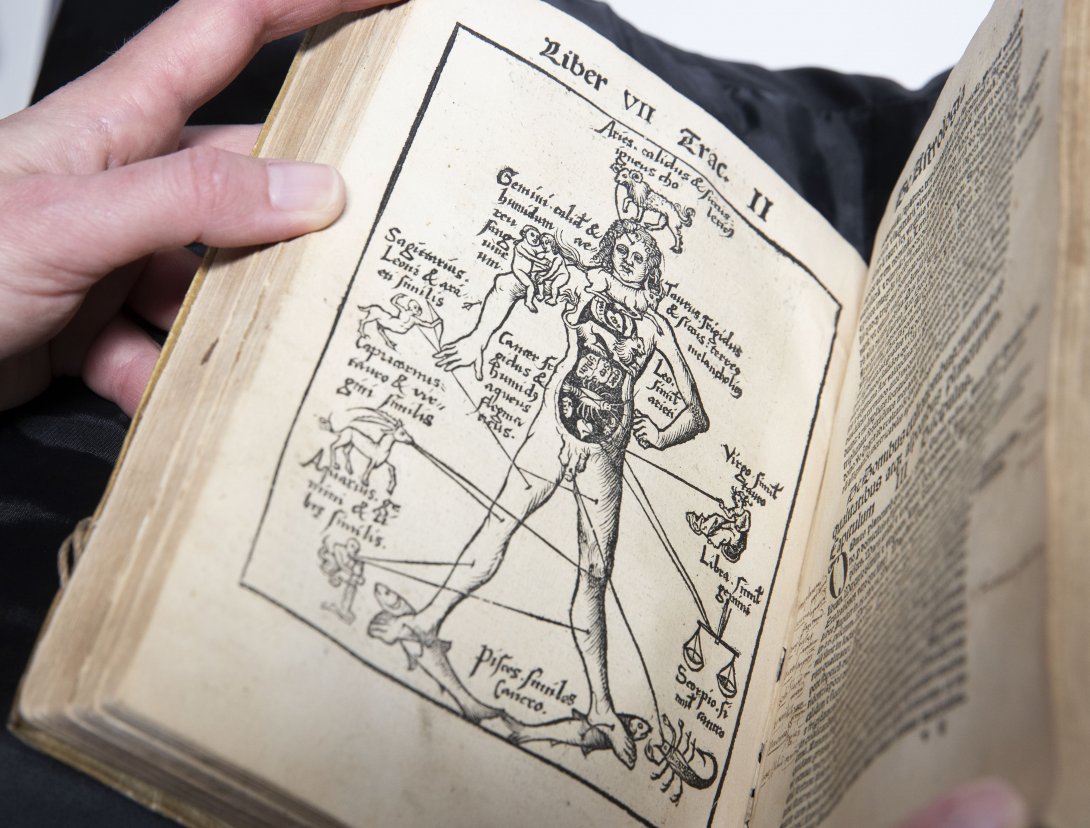

Each section of the book is introduced by its own full-page woodcut.

The first book is about Grammar, represented here as the key to or foundation of all learning. Nicostrata, the goddess credited with introducing the Latin alphabet, leads a student towards the tower of the Liberal Arts. Metaphysics and Theology (represented by theologian Peter Lombard) are at the top, a statement about their importance.

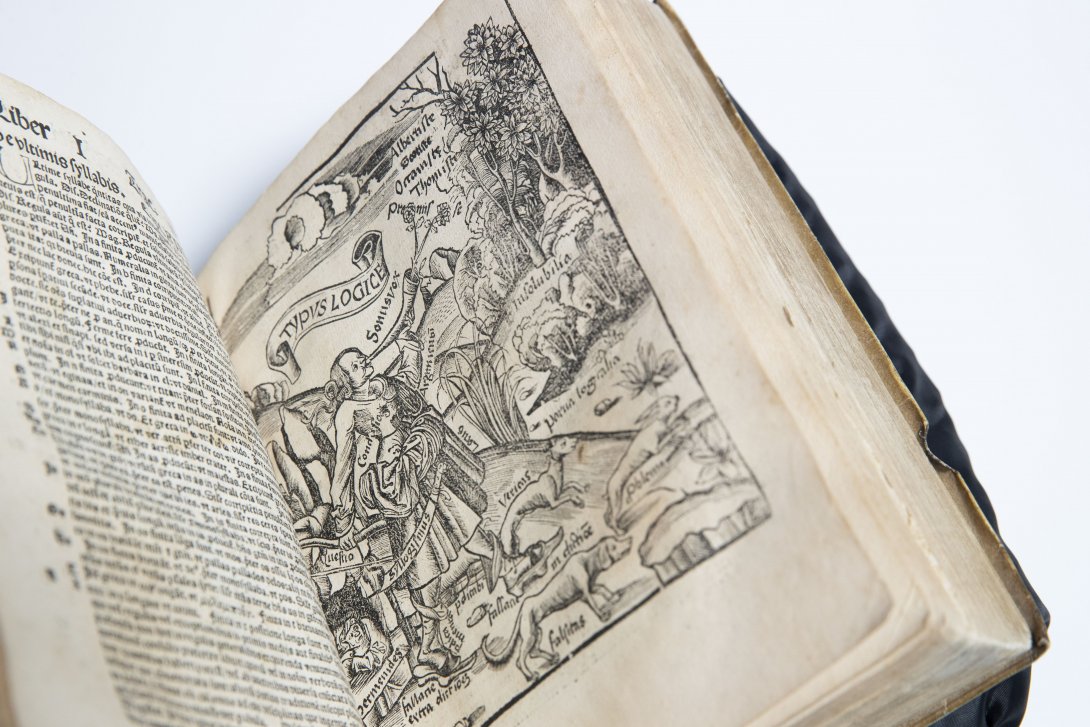

Logic is going hunting, in pursuit of a hare (named Latin for ‘problem’), with her dogs ‘truth’ and ‘falsity’ armed with the bow ‘questio’, meaning research or inquiry.

Gregor Reisch was a Carthusian, a religious order with contemplation central to their way of life, allowing for both the hermit and community life. The writing and production of books was important to Reisch's silent order at Freiburg-im-Breisgau. Reisch was well connected in the world of letters—he helped the great scholar Erasmus with his edition of the works of St Jerome. Erasmus, in turn, called him an ‘oracle’. One of Reisch’s students was Martin Waldseemüller, known today for his printed world map of 1507—the first printed map published with the name America on the separate continent. Only one copy of that first edition survives at the Library of Congress. Waldseemüller in fact contributed maps and words to editions of the Margarita, unfortunately not this one.

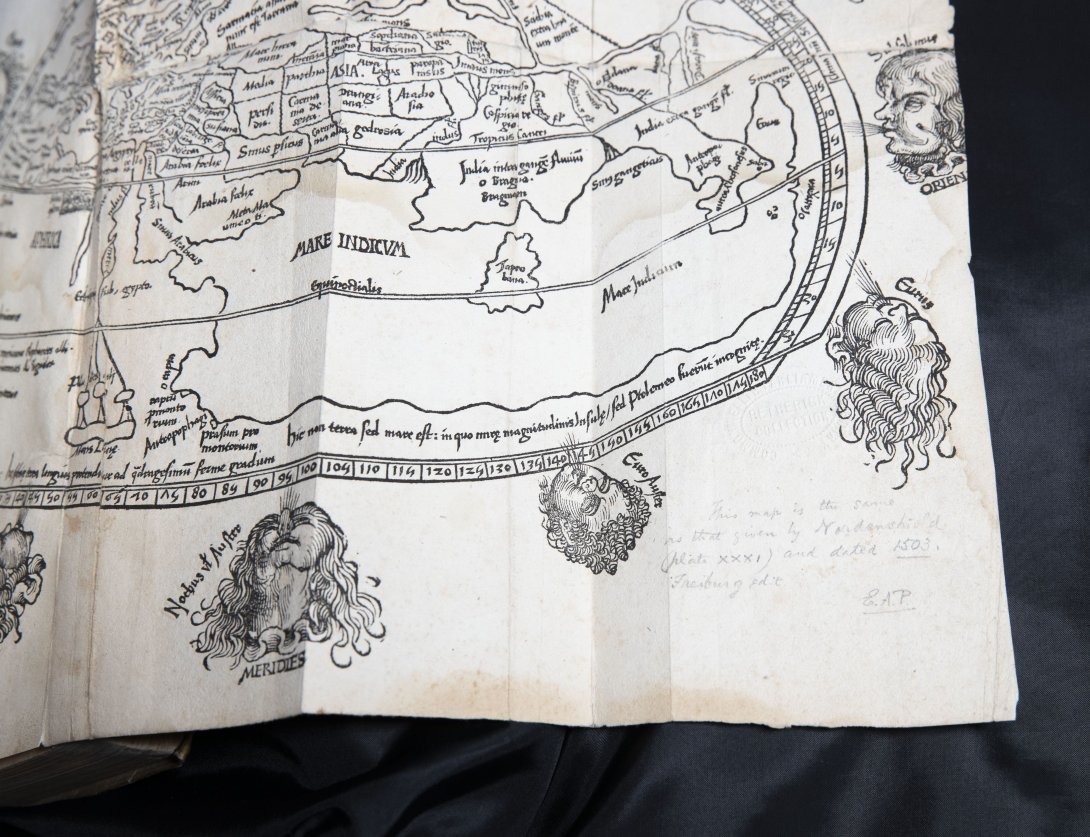

Our Margarita Philosophica was once owned by Edward Augustus Petherick, whose collections are at the centre of the Library’s collections and history. Petherick was London agent for Australian bookseller George Robertson, and sold his collection to the Commonwealth of Australia in 1909. It is thanks to Petherick and his varied interests that we hold letters by Jane Austen and George Eliot, the Doncker Atlas (1659), the manuscript Vlamingh charts of Western Australia (1697–1726) and many rare books relating to Australia. See this guide for more about his collection.

The Margarita Philosophica is one of the oldest books Petherick collected. He clearly thought much of it, as he has annotated it and stuck his bookplate to the front endpaper, which he very rarely did. (At this stage, we know of five in the Library's collection.) Long serving former Library staff member Philip Jackson wrote a blog about Petherick’s bookplate.

The Margarita Philosophica was very popular during the 16th century, and many editions, including pirate copies, were produced, the last in 1600. The book is not as well-known as it could be, considering its scope and illustrations.

Its many and varied woodcut illustrations are fascinating, at least for me. Woodblocks were used for printing in China prior to 220 CE and in Japan from the eighth century CE, at first onto textiles, and later onto paper. In Europe, they were used from around 1400 CE. A design is drawn, this design is then traced onto a block of wood, which is then cut in relief. The block is inked, then pressed onto paper.

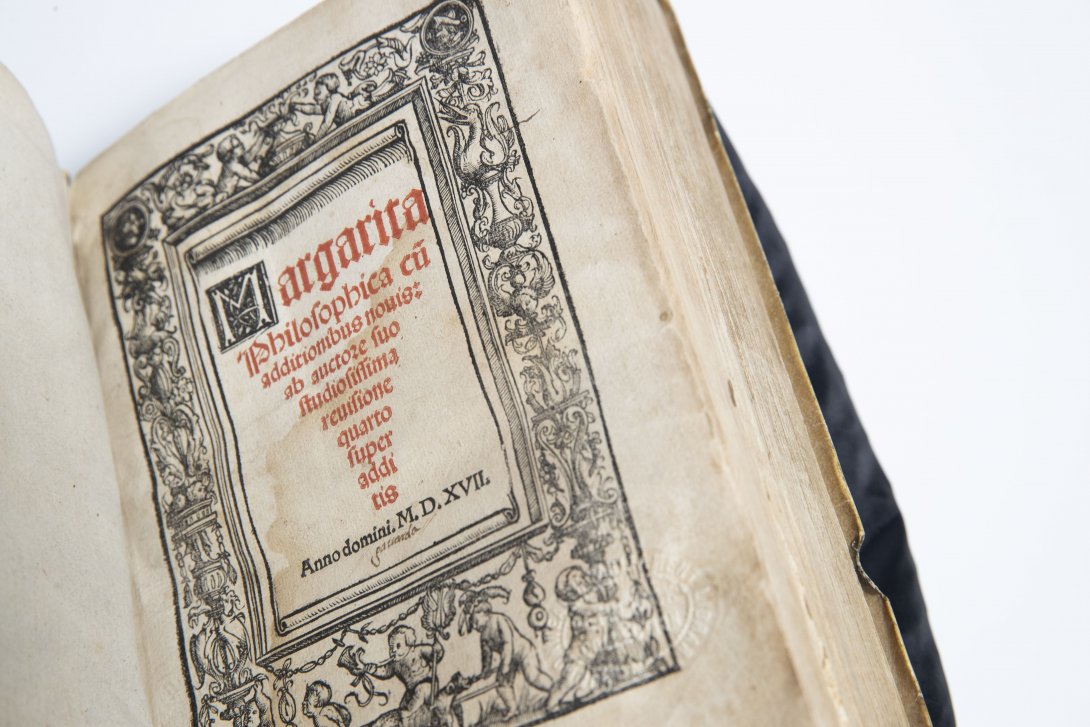

Our copy of the book is uncoloured, except for the red printed letters on the title page (as below) but some surviving copies are hand-coloured. The book had a complicated genesis: Reisch wrote it in the 1490s, and went through several printers. It is likely that several artists designed the many woodcuts. Remarkably, letters survive from 1498 by Swiss artist Alban Graf about his work on the book, which you can read at this link.

Ambrosius Holbein (c. 1494–c.1519), elder brother of the portraitist Hans, is said to have designed the border of the title page of this 1517 edition. Ambrosius designed the famous frontispiece of Sir Thomas More’s Utopia—we hold the third, 1518 edition. More was a great friend of Erasmus, who likewise knew Reisch. It is also interesting that this border was later used for a publication by Martin Luther.

The woodcuts throughout the book draw on medieval and early modern illustrative, cosmographical and cartographical traditions and update them. The 1517 edition’s woodcuts are very similar to those of the 1508 edition.

It is almost certain, however, that Petherick acquired the book for its maps—cartography being one of his great interests. They are found in the book on Astronomy.

Here you see Astronomy behind a crowned Ptolemy—the 2nd-century CE Alexandrian thinker, who is making observations with a quadrant. Who is teaching whom? Whatever the case, it argues that Ptolemy is very important to the study of astronomy.

This woodcut shows a geocentric view of the Cosmos. Atlas, the Titan of ancient Greek myth, is at the centre of this woodcut, with Earth just at his bottom.

This representation of the Earth is a ‘zonal map’, which identifies the Earth as a globe, the polar regions as uninhabitable, temperate zones as inhabitable, and the torrid zone around the Equator as uninhabitable.

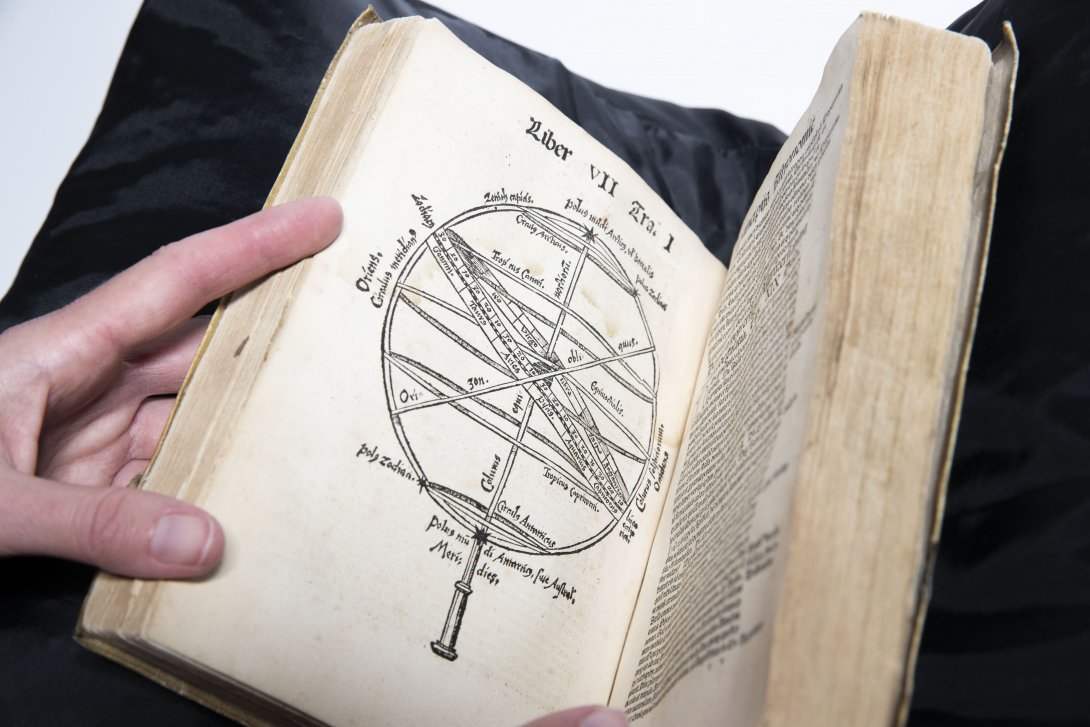

This is an armillary sphere, an instrument for making astronomical calculations, on the basis that the Earth is at the centre of the universe.

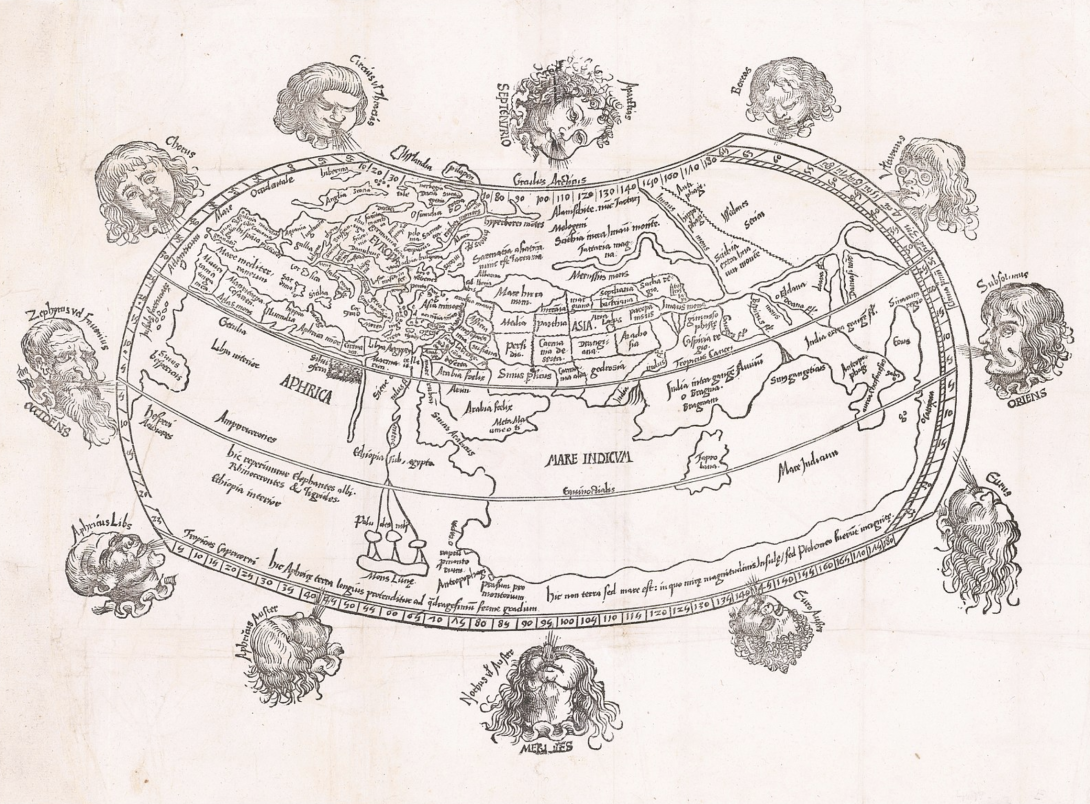

I was most surprised, however, to find this world map in the book.

These world maps are rarely found intact in copies of the Margarita Philosophica. Perhaps because they are so lovely. In his Geography, Ptolemy demonstrated how to project the globe onto a plane surface. In a revolutionary move, Ptolemy provided coordinates for over 8,000 places across the known world, expressed in degrees of longitude and latitude.

The map is very similar to the 1482 Ulm edition of Ptolemy's Geography, with some updates.

Our region has the text: ‘Hic non terra sed mare est: in quo mire magnitudinis Insule, sed Ptolemeo fuerunt incognite.’ (Here is not land, but sea, in which are islands, that were unknown to Ptolemy.)

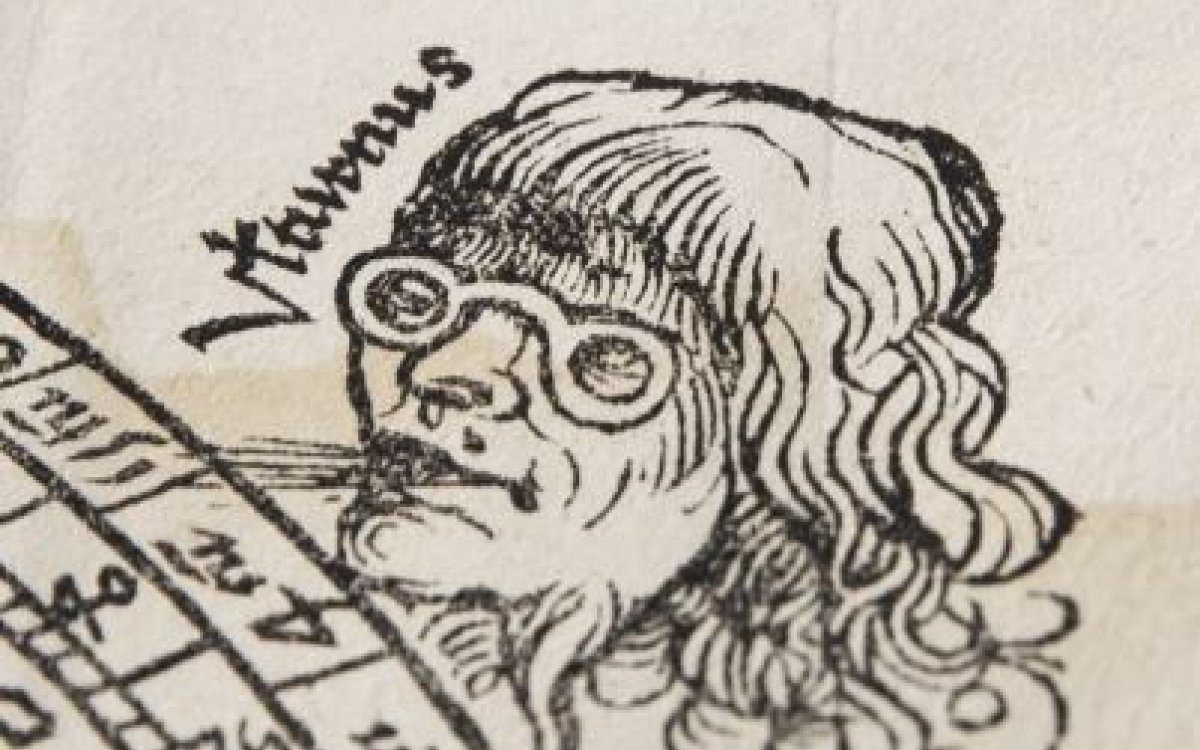

The Margarita Philosophica map departs from the Ulm edition in one major way. It has wind heads that are all different, some rather quirky, even one with spectacles.

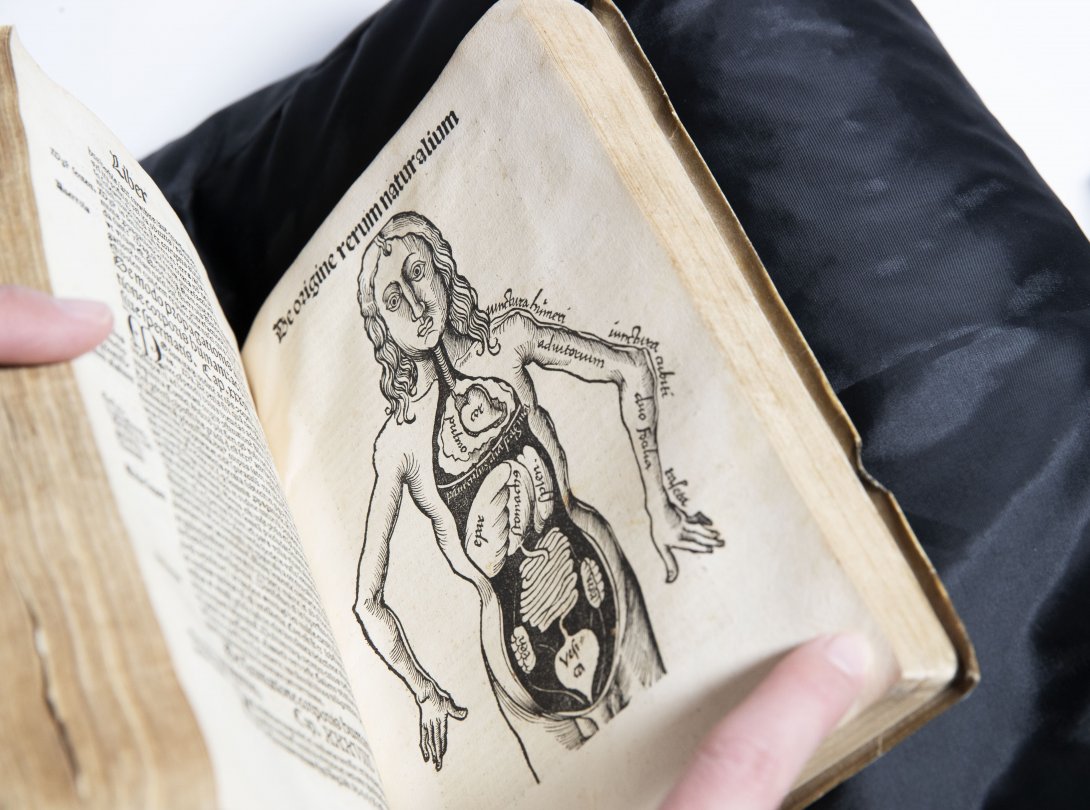

It is interesting to note that this, like other contemporary depictions, shows the human liver with several lobes. The liver is the left organ, on the same level as the elbow (beside it are the stomach and spleen). The human liver has only 2 lobes. This one has more than that. Artists’ access to the human body was limited at this time, so artists drew and printed what they knew—pigs’ livers have several lobes.

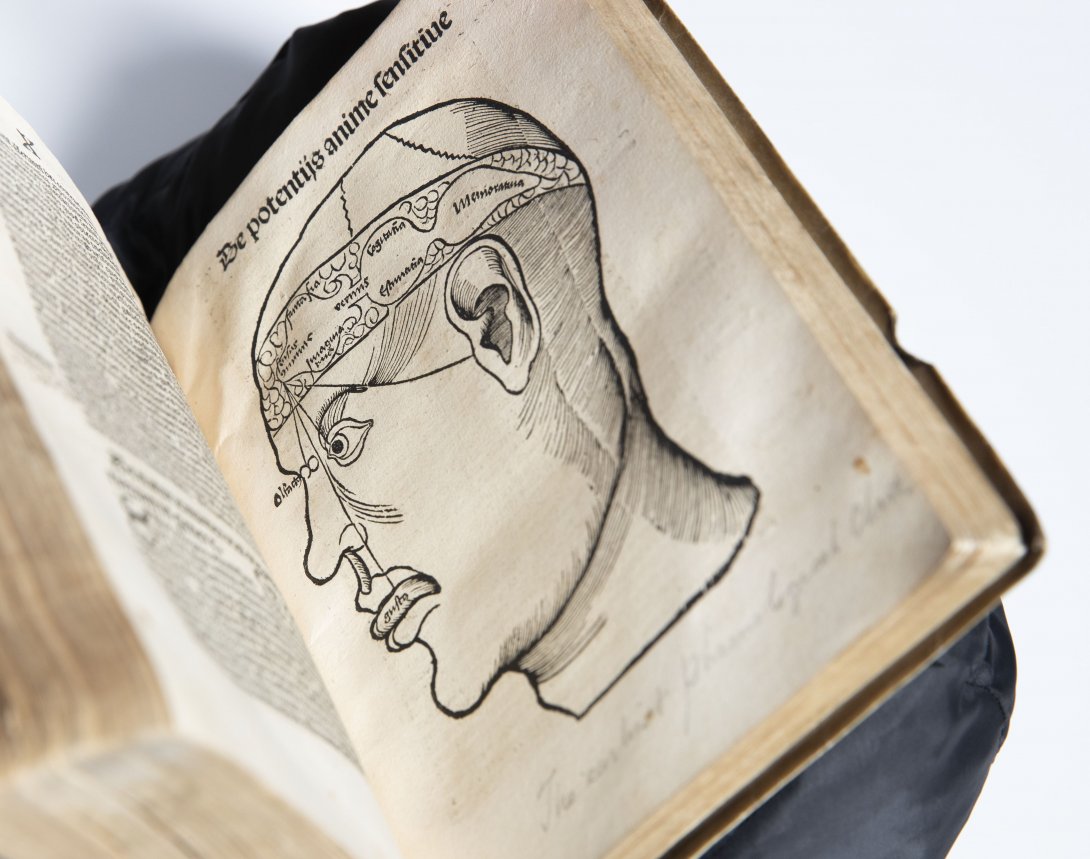

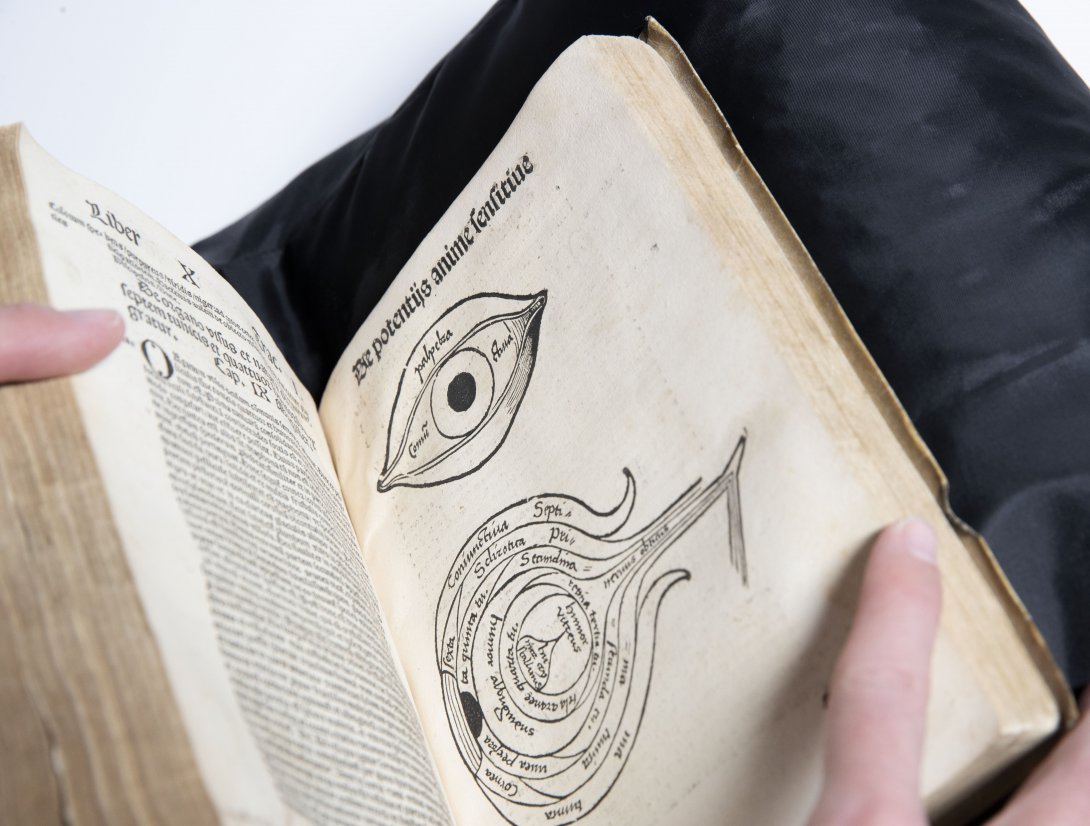

Headed with the Latin for ‘Of the power of the mind’, this woodcut shows the human brain as having three connected parts—imagination at the front, thinking in the middle and memory at the back.

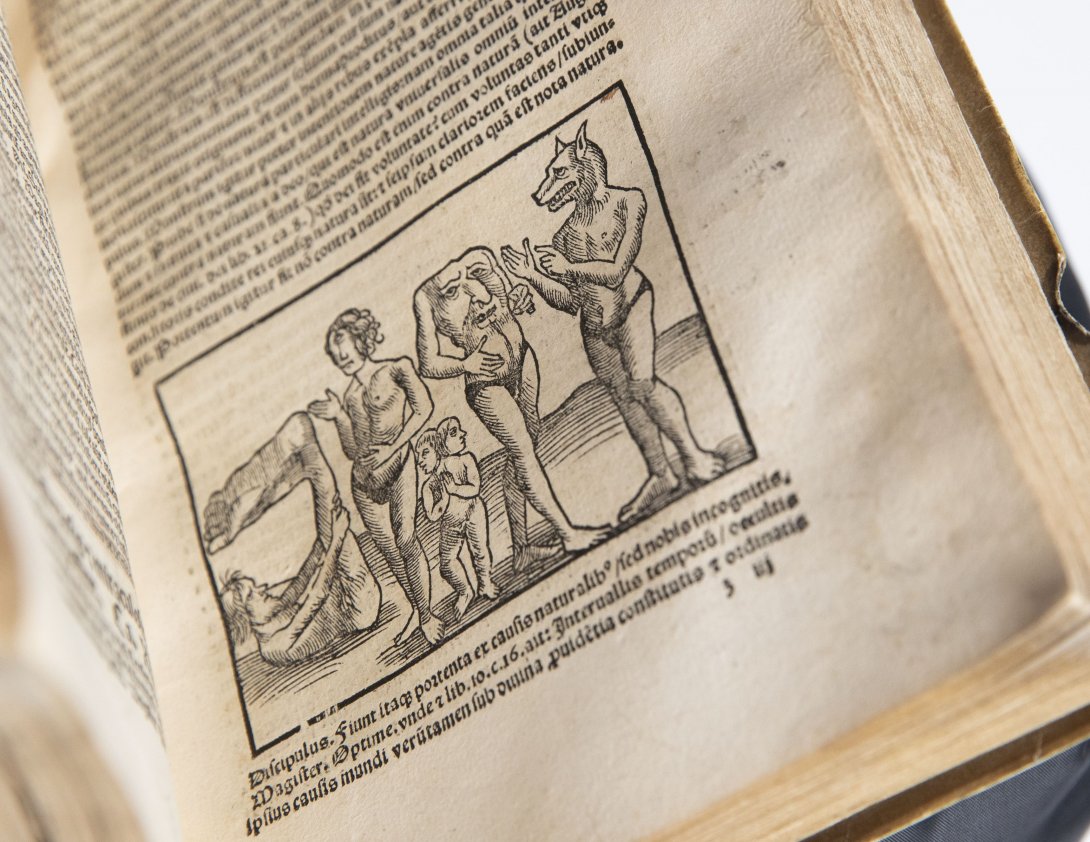

To end, it has some of my favourite beings in a small woodcut, both mythical and very real conjoined human twins. Left to right you see the Sciopod with a large leg and foot, a Cyclops with one central eye, a Blemmyae with his face in his chests; and the Dogheaded Cynocephali.

You can read the Bavarian State Library’s copy of Gregor Reisch, Margarita Philosophica (1517) online at this link.

The National Library of Australia’s Rare Books Collection is full of unexpected treasures. This has to be one of my favourites. Join the National Library or search our catalogue for more.

Dr Susannah Helman is Rare Books and Music Curator, National Library of Australia