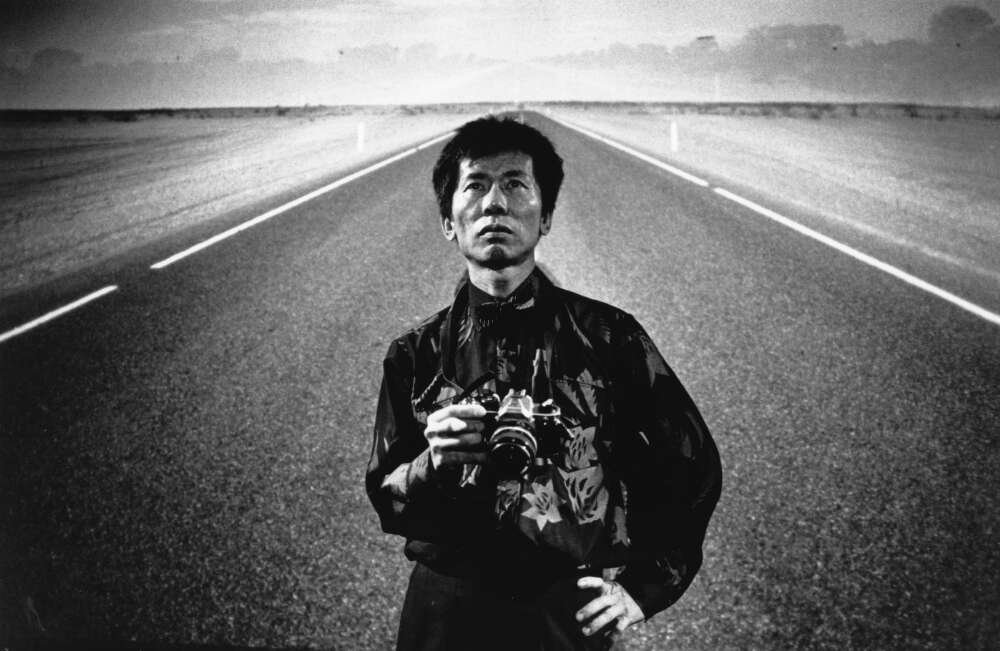

The National Library of Australia is home to the collections of Australia’s great storytellers. William Yang is one of them.

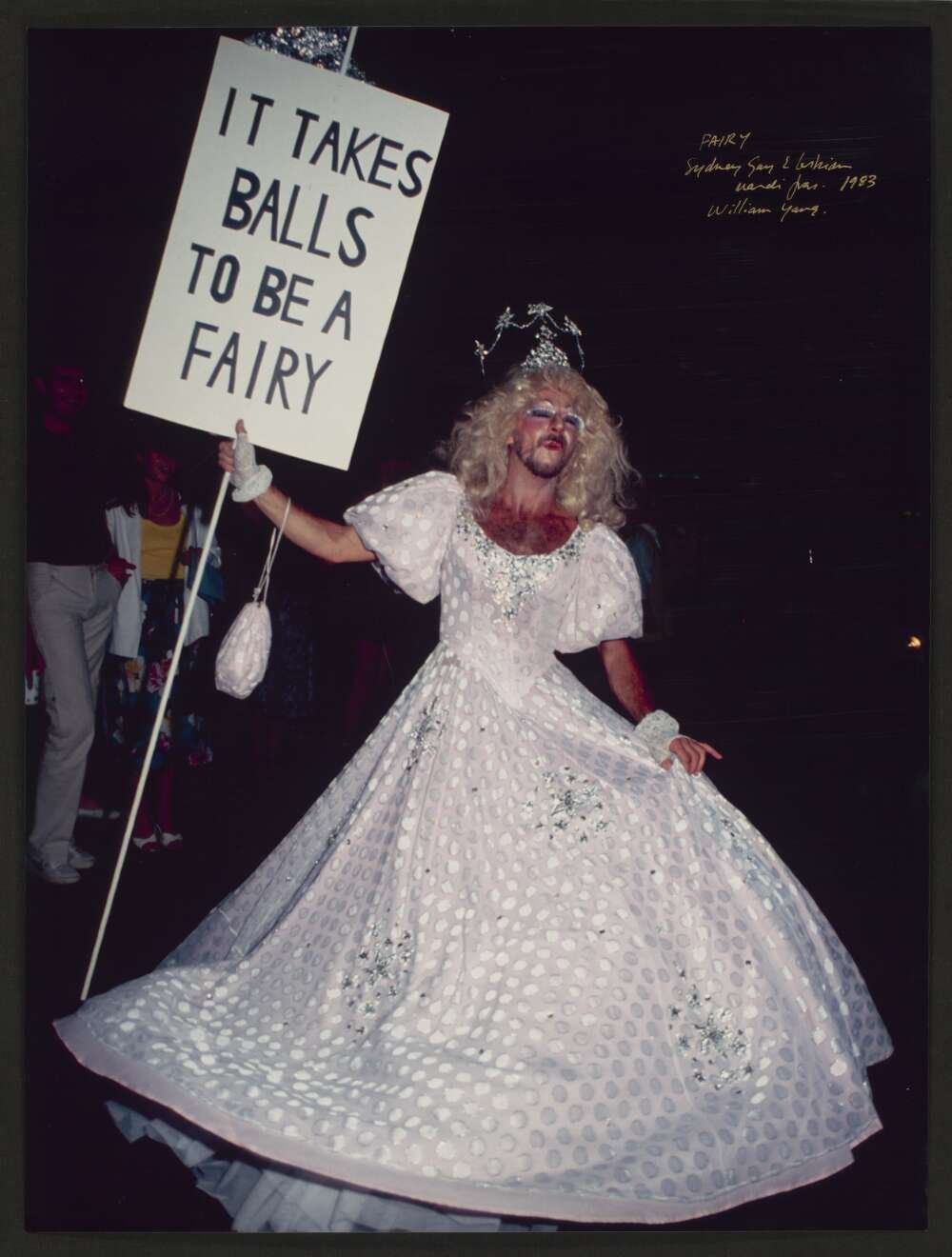

More than 250 of Yang’s photographs are held by the Library. Among them are series relating to artists, writers, actors, celebrities, friends, Chinese Australians, intimate dinners, boisterous parties, and the Sydney Gay and Lesbian Mardi Gras. The Library’s new Collections-in-Focus exhibition, William Yang’s Mardi Gras, showcases material from over 20 years of photography documenting Australia’s most fabulous parade.

Born in Mareeba, North Queensland, in 1943, Yang grew up in the small, rural town of Dimbulah, in the Atherton Tablelands. The grandchild of immigrants from southern China, Yang recalls how keen his family was for he and his siblings to fit in with European Australians: ‘My mother wanted us to be more Australian than the Australians’. His mother spoke Cantonese and his father spoke Hakka – two mutually unintelligible languages – and subsequently their family spoke English to each other. Yang and his siblings were taught neither Cantonese or Hakka.

In 1969 he moved to Sydney to pursue a career as a playwright, but found work instead as a freelance photographer, with a focus on social events. Yang’s photography first garnered acclaim in 1977 with the opening of his first solo-exhibition Sydneyphiles at the Australian Centre for Photography.

The show provided audiences with an almost voyeuristic look into the private lives and parties of communities rarely seen by Sydneysiders outside of them: artists, actors, directors, fashion designers, socialites, and Sydney’s gay community. It was the last group that was considered so controversial at the time. Acts of homosexuality were illegal in New South Wales until 1984, and never had photographs of gay life, love, and sex been displayed so publicly in Australia. People who allowed Yang to photograph them risked being fired from their jobs, or ostracised by family if they were seen by the wrong person.

Despite the risks, what Yang discovered while exhibiting Sydneyphiles was that ‘what people liked most was looking at pictures of themselves’; that having their identities represented, and being publicly acknowledged was significant to people.

In 1978, just a year after Sydneyphiles opened, the pressure of the Australian gay liberation movement came to a head. The newly formed Gay Solidarity Group held a demonstration to mark the 9th anniversary of the Stonewall riots that had followed a police raid on a gay bar in New York. It was by no means Australia’s first gay rights march, but what distinguished this one was the evening parade: the Mardi Gras, a celebration of queer pride held at the end of the day of protest. Despite a permit having been issued for the parade, the police response was brutal: 53 people were arrested, and there were widespread reports of police violence. The concern that had arisen around Sydneyphiles was realised when the names of those arrested were published by the press, resulting in many being fired from their jobs.

Due to illness, Yang spent the first three years of Mardi Gras parades convalescing in Queensland. On his return to Sydney in time for the 1981 parade (the first year the event was held in summer) Peter Tully insisted that Yang document the parade, and since then Yang has become one of the Sydney Gay and Lesbian Mardi Gras’ preeminent chroniclers.

In exhibiting these photographs together, we see that his long connection with Mardi Gras allows Yang to approach the event in the same way that he approaches his other subjects: his friends and family.

Yang contextualises his own photographs alongside heirloom family snapshots in part diary and part family slide night performances. In his performances he remembers people and places important to his audiences with quiet openness and honesty. Yang creates a sense of intimacy between the audience, his subjects and himself. He invites the audience to feel what they feel without imposing his own emotions on them.

In documenting his subjects over a period of weeks, months, or years, Yang invites the audiences into the lives, the experiences, and frequently into the deaths of those closest to him. For the Mardi Gras that means watching the parade grow and change. What began as a protest event celebrating queer life, also became a community event; an artistic event; an event to remember people of the community lost to the HIV/AIDS epidemic.

In his monologue Friends of Dorothy, after years of documenting the Sydney Gay and Lesbian Mardi Gras, Yang concludes:

I’ve finally figured out what Mardi Gras is. It’s the re-enactment of a ritual. A ritual we have worked out over the years as defining and celebrating a gay, lesbian, bisexual, transgender and intersex culture.

William Yang’s Mardi Gras is on display at the Library in the collections-in-focus space within the Treasures Gallery now.