*Speakers: Shirley Hedditch (S), Ginger Gorman (G), Jeni Haynes (J)

*Audience: (A)

*Location:

*Date: 11/11/22

S: Good evening. A very warm welcome to the National Library of Australia and to this very special event, Jeni Haynes in conversation with Ginger Gorman. I’m Shirley Hedditch, I’m the Director of the Human Resources here at the National Library.

As we begin I would like to acknowledge Australia’s first nations people, the first Australians as the traditional owners and custodians of this land and give my respect to their elders past and present and through them to all Australian Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people.

Thank you for attending this event either in person or online coming to you from the National Library building, beautiful building on our beautiful Ngunnawal and Ngambri country.

If this event brings up any issues for you or if you feel like you need to speak to someone please call 1800 Respect which is 1800 737 732, the National Sexual Assault Domestic and Family Violence counselling service. It doesn’t matter where you live, they will take your call and if need be refer you to a service closer to your home. For crisis support contact Lifeline on 13 11 14, chat with them online at www.lifeline.org.au crisis chat or text them on 0477 13 11 14. Lifeline services are available 24/7.

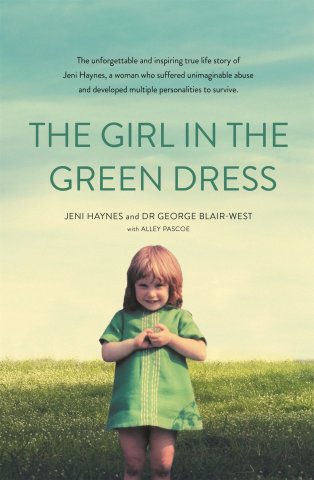

Dr Jeni Haynes and Ginger Gorman are here tonight to share with us Jeni’s unique and important story. The Girl in the Green Dress is an unforgettable memoir from a woman who refused to be silenced, what a woman, amazing. Dr Jennifer Haynes grew up in Greenacre in Sydney’s western suburbs. After injuring horrific abuse Jeni fought for years to bring her father before the courts to face justice for what he had done. In doing so she created legal history. Jeni spent 18 years at university, graduating with a degree in psychology, a masters in legal studies and criminal justice as well as a PhD focusing on victims of crime. Amazing achievement.

The fact that Jeni survived is testament to the extraordinary strength of her mind. What saved her was a process of dissociation, multiple personal disorder, MPD or dissociative identity disorder, DID, a defence mechanism that saw Jeni create over 2,500 separate personalities altered who protected her as best as they could from the trauma. With the support of her psychiatrist, Dr George Blair-West, Jeni fought to create a life for herself and bring her father to justice.

Ginger Gorman is an award-wining print and radio journalist based here in Canberra in the ACT. She’s also a 2006 World Press Institute Fellow. Her freelance work has been published in print and online in publications such as news.com.au, The Huffington Post, The Guardian, The Age, Mamamia and the ABC’s Drum website. Her first book, Troll Hunting, was published in 2019. Please join me in welcoming Jeni Haynes and Ginger Gorman to discuss Jeni’s book, The Girl in the Green Dress.

Applause

G: Thank you so much, Shirley.

S: Thank you.

G: Actually a lot of Troll Hunting was written here at the National Library so I’m very fond of the National Library. Thanks for that lovely welcome. So isn’t it great to be in a room with real people after the pandemic? I think the pandemic taught us that it’s lovely to see people face-to-face so welcome everybody who’s here face-to-face and welcome to those here who are joining online and a lot of my mates couldn’t make it in person but they’re here online.

So before kicking off I would also like to acknowledge that we are on Aboriginal land and this land was never ceded. This is the land of the Ngunnawal people and I’d like to respect their elders too and give a big shout-out to them, past and present and also acknowledge that the Ngunnawal people are great storytellers and that’s what we’re going to be doing here tonight.

So before we get started just a few little things. At times we’re going to be talking about very difficult issues and I’m hoping Stuart and the team are going to put the numbers up here so if you need help please reach out to these numbers and we also wanted you to know tonight if you need to step out at any time just go for it, we’re among friends here. You can step out, you can come back, we’re very casual tonight, aren’t we, Jeni?

J: Oh yes.

G: We want you to feel comfortable. There’s also a few things that Jeni’s asked me not to talk about tonight. We’re going to have a good old yarn, don’t worry, we’re going to have a good old gossip here on stage but if you’re wondering oh I’ve read the book and there’s a few things that Ginger’s not getting to, that’s why.

We’re going to crack on now so as Shirley suggested Jeni is the most extraordinary person and she is a living, breathing example of the strength of the human spirit so I’ve never come across someone so brave, so unbreakable and I’ve lived in a lot of countries, Jeni, and I’ve been around the block a few times so as Shirley said from the time Jeni was very small her father abused her and tortured her in ways that are really unimaginable. It’s just sadistic, really, to think about. Her brain did something quite amazing, created these alters or multiple personalities, not just a few but 2,500, big effort.

J: Big effort, yes, absolutely, no effort at all, they just sauntered out the back of my head.

G: So some people call this dissociative personality disorder or DID but Jeni prefers the term MPD or multiple personality disorder so that’s mostly what we’re going to be using tonight. Also as Shirley shared, and I just found this amazing when I was reading about it, I just went and Googled everything about you and I was reading all the BBC articles about how Jeni made legal history not just here in Australia but around the world when her alters were allowed to testify in court. Jeni and her alters put her father in jail for 45 years so this is what her book, The Girl in the Green Dress, is about. It’s co-written with Ali Pascoe and we’re not going to go into the details of Jeni’s abuse tonight because we don’t want to re-traumatise anyone, what we’re going to do is really unpick some of the things about the psychological issues and the legal issues and as Jeni’s talking her alters might pop up and they will usually introduce themselves as you’re here so it’s you and me and Jeni and we’ll see who visits us.

Jeni, first of all, I’m so grateful to you for surviving, I just feel very privileged to be here to talk to you today and I’m sure everybody in this room and also listening online feels the same. When I first picked up your book there was this beautiful quote right at the start, you said the happy ending is me. What did you mean by that?

J: Oh when I look back at my life I could easily see it as a sad life, horror but it’s not actually a horror story, in many ways my story is a love story, it’s a story of self-love and self-care and thinking about myself in a way that isn’t selfish in the way that we perceive selfish to be a negative thing but being aware of myself and what I needed and being able to provide it for myself, it’s a love story. So at the end of this it’s got a happy ending and that happy ending is the Jeni sitting here today where I’ve jettisoned all the baggy clothing – I’ve kept the butterflies, got to keep the butterflies but being sensual, sexual being which is some of the biggest challenges I faced and yet to be able to do that that makes me smile, that makes me happy. So I’m the happy ending. When I walk out of here I’m not a sad person, I’ll be walking out of here as joyously as I walked in here because I’m happy, at long last I know what happy really is.

G: We were talking just before the microphones were turned on about how much Jeni loves playing games and the other thing we were talking about is Jeni loves ‘50s clothing so you might think it’s an accident that I’m dressed up with a flower in my hair but it’s not, it’s in honour of Jeni and we discussed our outfits before we came on stage here because you’ve deliberately worked to put all this joy back into your adult life that you didn’t have in childhood.

J: Absolutely. When I was a child I wanted to do ballet. Can you imagine my father’s face? Yeah, you don’t wear very much when you do ballet and the bruises would have shown so no ballet. But I wanted that sense of being in control of my body and I didn’t have that and I’ve had this craving all my life for the ‘50s outfits, the beautiful, glamorous ‘50s. I was talking to a friend of mine who painted me for the Archibald, Renee Broders, and she said if you could have anything what – if you could have you looking like anything what would you – I’d be in a ‘50s poodle skirt, I said. [unclear 10:40] not on your nelly. I’m in a ‘50s poodle dress.

G: There’s a petticoat underneath and just so you all know, Jeni also has butterflies on her shoes as well as her dress.

J: So for me it’s embracing, it’s taking what was oh I’d always love to do and saying well why am I not? Why not wear ‘50s? Why not have an Audrey Hepburn hairdo? What’s stopping me? Well it’s not him anymore, he’s in jail, he can’t stop me.

G: Okay, let’s talk about that so in 2019 you were allowed to testify in court along with your alters and you put your dad in jail for 45 years. What was it like to use the damage that he had done to you and your alters against him in a legal sense in that very formal justice setting of a court?

J: People think it’s crazy but it was amusing, it was actually rather amusing. To be able to use those things that he’d used to call me crazy against him was – it was symbolic, it was amusing. It was also terrifying because I didn’t realise that was the first person with MPD ever to get justice, I didn’t realise I was the first person with MPD ever allowed to testify and I didn’t realise that the police were going to use the very things I was trying to minimise, my multiple personalities, my physical injuries, I didn’t realise they were using them as evidence against my dad because I went to the police to protect the unknown child. I never went to the police to get justice for me because I didn’t know that justice and me could even be put in a sentence together. So I tried to hide my multiplicity because I thought that it would decrease my credibility and yet it actually increased my credibility because it was a known in psychiatric circles, it was known that MPD could be a result of serious sex crimes. But I was the first person to ever walk into a courtroom and say yeah, it is and here I am, deal with it.

G: Here we are.

J: Yes, yes.

G: We’re going to unpick that in just a moment but can you explain to people here today what you mean by the unknown child?

J: Ah. My father, the monster that he is, loves control so I was terrified that he would find a single woman with children and get into a parental role over that child and start again. And so I went to court, I went to the police, I went everywhere to protect a child that I would never know.

G: But not for justice for yourself.

J: God, no. Wasn’t about me at all, it was about making sure he could not do this to somebody else because I was taught throughout my entire experiences that I didn’t matter, I’ve never mattered and if you don’t matter you don’t go for justice because you don’t know you’re allowed to. So I went to stop him ever hurting another child and he had been pitched as someone that was dangerous to teenagers and so it was really hard for me when I stopped monitoring him and I went to the police and said it’s your job now, I cannot stand another minute of this man in my life, you have to take care, you’ve got to start protecting, not expecting me to do it and you’ve got to start protecting when this – when the child enters his life at zero, not at 15 because by the time you get to 15 he’s had 15 years of the kinds of things he did to me and I refused to let him do that to anybody else ever again.

G: I want to talk to you about the police handled this in just a moment but you said a really interesting thing just a moment ago and I find this remarkable and this is that in fact your alters helped you testify against your father because they remembered things that Jeni didn’t remember. So can you explain to us how in fact your MPD helped you recall the evidence against your dad and convict him whereas most people would have thought she’s bonkers?

J: Oh yes, yes, I’m bonkers. Officially I’m clearly bonkers although my psychiatrist says there’s nothing wrong with me.

G: With your doctor that you’ve got -

J: Yeah but you know I was bonkers to study as well. But to begin with the question, okay. When I came to write my statement police told me write everything you remember. At that point I was a integrated person who had previously had multiple personality disorder and when I came to actually write the statement it was like watching the big screen. I didn’t see the computer in front of me, I didn’t feel myself typing, I would watch on the big screen that was in front of my eyes and three hours later I’d roll away from the table and there would be 5,000 words written. What would happen was while I was piecing the memories together there were other alters typing, there were other alters coming along and adding the sounds, the smells, the tastes. And so it was like creating a jigsaw puzzle and each alter had a different piece and that’s how we survived that, was by breaking up each experience into jigsaw puzzle pieces so some poor bugger got stuck with what he smelt like, there was a lot of people that had to deal with that and others dealt with what we heard and the emotional content of what we heard. So when we came to write it back it was comparatively simple. The student, the one with the three degrees just went – and 5,000 words just ran out of her fingers.

G: But just to be clear here so Jeni and her alters wrote nearly a million words.

J: Yeah, never ask me to write down everything I remember unless you have a long time to read it because it was enormous. And the reason why it was enormous was because I’d been told I was a liar, a fantasist so much that I wrote everything down to the individual colours on his multi-coloured jumper because I wanted to prove that I was telling the truth. Instead of walking into the police station and saying have I got a story for you? I walked in, almost slunk in going I want you to protect this unknown child and the only way I can do that is to tell you what this monster did to me but I don’t matter, I just want you to know what he did so that you can make sure he doesn’t do it to anybody else. It’s a very strange way of presenting a case because for – the court case went for 10 – sorry, the legal process went for a total of 24 years, the last piece, the 10-year process is the Australian bit and – it’s a long time.

And I talked about the unknown child so much that one day Paul Stemulers, my police officer, stopped me and he said I don’t care about the unknown child, that’s not what I’m here for, I want to get justice for the child I know about. We’re eight years into the legal process by this stage and it’s only just hitting me that this legal process isn’t about the unknown child, it’s about me. And that shook me and it took a long time for that to percolate through but when it did it hit Symphony like a ton of bricks because suddenly she realised that for Paul Stemulers she mattered and he’s our hero. Him and Kim Whitman and Rachel Lawson and Rod Masser, hero cops, all of them, they are amazing. They did everything they said they were going to do. Sure it took a while but they did everything that they said they were going to do and they were amazing but it took me a long time to work out it was about me. It didn’t cross my mind that these police officers were getting upset because it happened to me.

G: But that’s really validating, isn’t it?

J: It is, well it is when you finally register that so when I go into the courtroom on the first day of the trial and Dad walks in and I’m ready, prepared and there’s about 1,000 alters sitting there ready to throw the puzzle pieces out and he thinks he’s walking in to deal with this child that he can just intimidate and -

G: There’s a lot of you.

J: Yeah, yeah.

G: Just for people who are listening who don’t know anything about Jeni’s case, Symphony is – would you call her your original alter?

J: It’s almost like Mum had twins. It’s the strangest thing, I can’t explain it any better. Mum had produced a single-bodied child that had a twin head. There was Jennifer Margaret Linda, the original child and she lasts six months and then her life – her interaction with the world ceases. Symphony arrives and it’s like I can’t remember a time when we didn’t have Symphony, there’s no moment when she arrived, she was always there. We are the arrivals so I’m the entity currently known as Jeni doing the tech-nucky stuff. Symphony created all of us and quite unconsciously. So the Jeni you’re talking to now is an alter. When Symphony arrives, and I know she will, you’ll be talking to all intents and purposes to the Jeni that you think you’re talking to but you’re not.

G: So listen, you feel empowered now and we’re all sitting here watching this amazing person in your gorgeous ‘50s dress but it took a long time to get justice. You said 24 years and I feel tired even hearing that number so what would you fix about the justice system if you could? If you could wave a magic wand right now.

J: Oh geez, what would I do? First thing – sorry, hi Muscles.

G: I was about to say we’re talking to Muscles.

J: Yes. First thing I would do is make sure that the police understand that if you have a person who’s been abused you’ve got to talk to them, not just get the evidence and bugger off but actually come back and say we’re working on your case. Don’t expect the victim to be able to chase you up because we can’t. We felt a nuisance if we phoned the police, we were wasting their time. I spent so much time trying to get the body to pick up the phone and call the cops and say how are things going? And the excuses I heard would go – I mean four million words all on their own. But it all came down to we don’t feel like we matter and when the police say we’ll call you on Tuesday and then they don’t so you stay home every Tuesday for six months because they didn’t specify which Tuesday they were going to ring so you best be home every Tuesday and then they never ring you. The messages that they give you reinforce what your abuser says, that you’re a piece of crap and you don’t matter and nobody cares about you.

The other thing I would say is I would say historic sex crimes need to be a priority. I had police officers, adorable police officers but they’re working in Bankstown. You know what happens in Bankstown? Lots of drive-by shootings so my police officer would sit down, I’m going to work on Jeni’s case this night, that’s it. Drive-by shooting, poof, not a thing was done. And then it just gets put in the folder and that’s how come everything takes 10 years. If you’ve got a victim that tells you that they have DID or MPD you know you’re in for the worst kinds of sex crimes possible, make it a beep, beep, beep priority, do not put it in the too hard basket.

G: You can swear.

J: Really? I got told I had to be beeping for this show.

G: Oh did you? Did you?

J: Yeah, I had to beep for the court -

G: I feel like we’re all grownups here, aren’t we?

J: We’re all friends, right?

G: We’re all grownups -

J: Well in that case if you say you’re going to phone somebody fuckin’ pick up the phone, even if it’s can’t talk to you today but we’re working on it. I mean I got told one word from you ruined the whole case. I phoned the cop and said what’s the word? If you tell me I won’t use it. Word was extradition but it took two years for them to tell me that but everything that I did, the secrecy. Okay so you get fucked by your dad, don’t tell, you get abused within the family, don’t tell then you go – you leave home if you’re lucky and you start to get into another world and then you try to talk to people and go oh I don’t want to hear it, don’t tell. Don’t tell me, oh it’s too horrible to hear. Then you go to the police and they say don’t tell. And the only people that protects is the fuckin’ abusers. We have a fucked up system in which we grant accused paedophiles, accused child molesters, accused monsters the assumption of innocence. They are innocent until proven guilty. Well I thought 900,000 words sure as shit proved it but no, we had to test it in a courtroom.

So he’s innocent which makes me an assumed liar for 24 years. I couldn’t even put hashtag me-too on my frickin’ Facebook page because that could kill the case ‘cause he’s watching. So secrecy, we need to have a system in which privacy is something that the victim can ask for as opposed to it being imposed upon them as a state of play. I had to wave our right to anonymity simply to get his name out there because he’s my dad therefore if we identify him we will automatically identify the victim. Only if you’re famous. Only if somebody’s lookin’ and only for family and if family haven’t worked out by the time you’ve gone to court that you’re telling the truth then they’re not worth talking to.

We had the situation where not allowed to talk meant not allowed to tell meant you can’t get support. If you’re not even allowed to hashtag me-too how can you get support from counsellors, some of the numbers you’ve put up on the screen? We’ve had difficulty every step of the way because we’ve had to be quiet, we can’t talk about it. It’s going through the courts. Well nobody said it’s going to take 10 flippin’ years.

G: But also that’s reiterating the trauma of actually what happened to you.

J: Oh yeah. The legal process itself right up to the very end, right up to the day that we walked into court to testify, the legal process, 24 years of it, did nothing but validate my dad. Can’t tell, you’re a liar, you – the first thing we do is we go check out your mental health history. Jeni did an enormous spiel in the book about how false -

G: Memories?

J: No, no. What’s the word? False diagnoses have an impact. If you are labelled as schizophrenic because you are misdiagnosed as schizophrenic instead of having MPD nobody comes along and rubs out that, it’s there for everybody to read and more importantly it’s there for your abuser and your abuser’s lawyers to read and then your mental health which is destroyed by them is now used by your abusers to batter you all over again. So my mental health was kept remarkably quiet by the police.

G: So when we had our Zoom call -

J: I’m not bonkers.

G: When we had our Zoom call you said to me – I said what is the one thing you want people to know? What’s the reason that you wrote the book? You said to me I want MPD destigmatised and I want to be seen as evidence of a crime -

J: That’s right.

G: Can you tell me about that?

J: Yeah. MPD or DID, whichever is your particular flavour, only occurs in situations or settings where you are faced with extreme overwhelming circumstances that you can’t escape and you can’t change. Now most of the time that is childhood sexual abuse. There are other circumstances, war and stuff like that but again you’ve got to be a child. If you’ve got MPD the people around you need to be able to go oh shit, trauma history, really bad trauma history, play gentle. And that will stop people like your family or your friends wanting to hear all the gruesome details. I’m supported under the NDIS and I’ve had support workers walk up and I say so what do you know about me? Plenty of information out there. What do you know about me? Oh I know nothing, I prefer to hear it from you. Right so you prefer to re-traumatise me, fantastic. Where would you like me to start? Shall we go to the babies first, second or shall we leave them out?

It re-traumatises us whereas when I get a good support worker and they say I’ve read your file, you don’t have to tell me anything, what do you want to do today? They’re the ones I keep but -

G: Hi Scotty.

J: Hi Scotty.

G: Scotty’s Jeni’s fabulous support worker who just took amazing photos of us [unclear 33:54].

J: Yeah, he’s one that walked in and said I read your file, I do not need you to tell me anything. And what he did was he and others like him took the burden of disclosure off me and that’s what we need to do when you’re faced with someone with DID, MPD or dissociative disorder not otherwise specified, DDNOS. So we’ve got a DID and then a DDNOS.

G: There’s a lot of acronyms, isn’t there?

J: I used to say I’m not a DID, I was a [done] 34:33 too. Sorry, I don’t mean to cut you off but -

G: It’s your show, Jeni.

J: - for me MPD equals trauma, the worst kinds of trauma so you’re going to be faced with somebody who has trauma. They have difficult relationships with family members or they may be completely away from their family members or they may be in a situation where they’re trying to back off to give themselves some space so that they can process things. If you say I prefer to hear it from you you’re basically saying I don’t respect you enough to read the little bit that you wrote for everybody to know about. So DID, MPD equals victim of crime, not fantasist, playing around or a liar because you can’t fake MPD consistently.

G: We don’t necessarily need to go into this but one of the most amazing things in Jeni’s book - as someone who’s had mental health issues myself and written a lot about mental health issues - is the way that you are treated by so-called mental health professionals and the stigmatisation there. And then the counterweight to that was when your psychiatrist, Dr George Blair-West, he writes that there’s possibly 100 million people on the planet with MPD so the question I have is why are we stigmatising this group which includes you and 100 million others when it’s so many of us?

J: Yeah. Well the numbers freaked us out.

G: Yeah, I can imagine.

J: The numbers were really scary. If you think 100 million people with MPD – hi, I’m Symphony.

G: Yes, I was going to say, are we talking to Symphony now?

J: Yeah. That’s 100 million people who grew up in a world like I did where you can’t trust anybody to help you, your job is to look after the mental and physical wellbeing of your family. A hundred million people living with a monster like my dad and I’m the first person to get justice, it’s terrifying. And it makes me so angry because I’m the first one with MPD to get justice. Why are we leaving the worst cases of abuse to be dealt with by the victim themselves? Because I had oh so many disgraceful things said about me, oh you can’t believe a word Jeni says, she’s got multiple personality disorder. So they wouldn’t believe my abuse history because I had MPD. The only way I get MPD is to have an abuse history.

G: Yeah, it’s the ultimate catch-22, isn’t it?

J: Yeah and so I spent so much time looking after psychologists and counsellors and the chapter on that got written and rewritten and rewritten and then we put names in and then we took names out but I will say one thing about this. We went to the Australian Federal Police in 1996 and we spoke to the amazing Kim Whitman and she told me that I needed to go and see counsellors so I did that. And arrangements were made between Kim representing the AFP and the support service that is unmentionable and -

G: For legal reasons.

J: For legal reasons because the unmentionables promised to take notes, they promised to document everything I said so I didn’t have to say it again and it was going to go in as evidence. Now Kim worked her butt off to get evidence to support me, to support my sister in the UK who was also attempting to get justice and I only went for justice to support her and to protect her and the unmentionables decided that I had MPD therefore I was crazy so they didn’t bother to document anything. So all of Kim’s hard work was wasted because the evidence was there, I re-experienced what Dad did to me in front of these people. They should have videoed me, they would have seen exactly what this monster did but because I have MPD they didn’t believe me and so my first ever disclosures – and of course for the police the first ever disclosures are the most important, they are the benchmark and they check if your story changes over time which it doesn’t - and this group of obnoxious women failed to document anything.

And they undermined my court case to the point that my dad was able to plead not guilty to me and the judge in the UK said that he’d said he was not guilty therefore he was not guilty. I’ve never forgiven the English for that, you know. So I’ve been declared a liar under English law because he did a plea bargain because he knew that if he pled guilty to me he’d never get out of jail and look, he pled guilty to me and got 45 years in jail. [Heaps] 41:23.

G: One of the things that you did in your book which is actually quite hard to read is - the abuse that you detail is quite graphic. Why did you make the decision to describe what happened to you in that way, what your dad did to you?

J: In many texts about abuse it’s hinted at. It’s obliterated by euphemisms and oh we won’t go there. And we made a conscious decision that we would tell at least a teaspoonful of what happened and then we edited out half the teaspoon because if people don’t know what extreme abuse is like they can’t recognise it and they don’t believe it when it’s right in front of them. If we live in a world of euphemisms we provide cover once again for our abusers. And if I say oh he touched me, he hurt me, you’ve got no idea what that means. If I say he made me pregnant at 10 you got a very clear idea of what he did to get me to that point which he did, unfortunately. It’s not right not to tell.

People need to know and sure, we get to the butt naked [whatoosy] 43:41 and we did that all through the book and we waved our tail feathers and you all got to hear quite a bit but I can assure you what you got in the book is the edited version of the edited, edited, edited, edited, edited, edited, edited book because we wrote and rewrote and rewrote and then we – oh the lawyers said no, can’t put that word in so take it out, what’s a better word? Put a different word in, no, no, we don’t like that one either. The problem is that by the time you get past your own filters, the publication filters, the legal filters, there’s substantial parts of my story that are not in that book because they were eliminated for legal reasons. And while I respect that there are parts of it that really irk me because my story, while being ultimately joyous, there were 14 years of shit to swim through first.

And what I wrote in the book that ultimately got taken out of the book for legal reasons was a demonstration of enormous psychological growth but because it was about a person that I wasn’t supposed to talk about it got cut. And what got cut was the story of my coming to terms with what my father did that occurred within the family unit and impacted everybody in that family unit. And it took me years to go from I hate you to you’d have never done this if not for Richard John Haynes. Any other man in your world, any other father, you’d have been a great sibling but I had to cut it and it irks me, it really irks me because I grew, I grew from the first page of that chapter all the way through to the end of that chapter and we lost that. But you know, got to respect the lawyers.

G: Solidarity, Jeni, because I’ve done a lot of reporting in this area of childhood sexual abuse and also domestic abuse and a lot of our laws stop a lot of stories being told.

J: They do.

G: Yeah.

J: Especially if it’s just – we got two jurisdictions here, we’ve got the English seven years and we’ve got the Australian seven years so Australia could only do the bits that took place in their country. We need a legal system that actually allows for a recognition that just because it happened outside of your jurisdiction doesn’t mean it didn’t happen and we need some courageous law changes to say a country, in my case England or Australia, can say we’re going to do the whole story. And yes, the laws in England are different but we’re going to apply the English laws to what occurred in England but tell the whole story because there are people out there that think I survived from four ‘til 11 and then it was all over. But six weeks old through to 14 years old, it’s a bigger, bolder story and I tried to capture that in the book without necessarily breaching -

G: All the laws.

J: It’s a minefield.

G: We are going to take some audience questions in a moment but I have one question that I really need to ask you and it’s a hairy question.

J: Ah yes.

G: So throughout this book one of the things that is remarkable is that none of the adults around you took care of you, none of them paid attention or took it to the police or did the things that as a mum I just can’t understand, I cannot understand this child going through this obvious abuse and no one paid attention. And the character at the centre of this is your mother, she’s living in the house with your family and your father and at times she seemed almost wilfully blind. She’s bathing you, you’ve got infections because of the abuse your Dad caused, you’ve got marks, terrible injuries to your body and the question that I ask and I know a lot of us here will be asking is how could your mother not know?

J: Okay. That is the hairiest question of them all. It’s a question that I’ve had a range of responses to over the years. I’ve defended, I’ve protected but when people talk about abuse and they talk about I would have known, how can you not have seen? Okay, I can’t explain why my mum didn’t see but I can explain what I did to make sure that she didn’t see. Over 1,000 alters were created simply to protect Mum. They were led by Captain Busby who I can feel is fast approaching. Their job was to protect Mum from Dad. Now a mother reading my book may say I would have seen, I would have known but that implies that you would have picked up on differences. How is my child different? They’ve been away for a school camp or they’ve been away for whatever and they’ve come back and they’re different.

I was never different. I was always abused. It’s not like I suddenly changed because Dad started abusing me at 12, I didn’t. I was abused from pretty much the minute I breathed. I was the punching bag, the slave, the scapegoat of my family. I had to protect my two siblings and my mum from my dad at all costs. I didn’t change. Changing meant that you could be seen. Hello, I’m Captain Busby. And hi Mum, I know you’re listening to this. Mum couldn’t see because I was busy hiding. If I got a bruise and she asked about it he told me if I tell my mother she will drop down dead in front of me, she will burn to death in a case of spontaneous human combustion. I’m not risking my mum – I fell at school, I knocked my leg multiple times against the desk at school. Multiple times, yes, it’s a big one so lots of times.

I had to lie and Symphony finds this really difficult because we pride ourselves on our honesty, we are honest when we should shut our mouths, really, but we couldn’t be because if we tell the truth, Dad’s doing this – and bear in mind I don’t have the words for it, it’s not like he tells me what he’s doing, all he tells me is I’m a dirty little girl and I deserve it. It’s punishment or it’s games. Stopped being games when I told Mum that I didn’t like them and the next day they became punishments. But I tried to tell, I did but he told me she could read my mind so I willed at her what he was doing. But he told me he could read my mind and if I even thought about telling he would kill my siblings. So is it reasonable to expect me to be able to tell when the next thing I know Frank could be dead on the floor in front of me? Or Sheila could be strangled? I couldn’t do that because I love my family. I love my mum, I would do anything for my mum. She’s my reason for existing. She’s my job. And my job was to keep her safe from the monster in our house.

Why Mum didn’t see I can’t answer but I can tell you this, Mum is a victim of domestic violence and coercive control. Everybody in the family where sex abuse is going on is a victim of domestic violence and coercive control because that is the essence of the psychopath that lives in your family. She couldn’t afford to see because what do you do? This is the ‘70s, divorce is not exactly you know the top choice in the ‘70s. Even in the ‘80s when she got divorced she was met by a friend in the ladies’ toilets who told her not to divorce the husband because things will change and you know your children will move out eventually. Thankfully she did not take that piece of advice but nonetheless it was given. Stay – people will say I stayed with my husband for the children. Get out, get out now while you have the chance because you don’t want to stay with someone who’s abusive for your children because your children are their prime victim. Dad did things to me and said things to me about my mum that I didn’t know whether to believe. I – your mum knows I’m doing this, your mum sent me to do this. You – why would I tell my mother if she already knows?

G: Yeah. It’s a very complicated situation which your book does really unpick in an incredible way.

J: We have to remember we’re children, it’s the adult’s responsibility to draw conclusions, it’s not the child’s responsibility to tell you in explicit detail what’s happening to them because we don’t have the words. I mean I didn’t even know it was a penis until I drew 12 copies of it, having told the police no, I never saw his penis. I never knew the name of this thing. I was 39 and saying no, I never saw it because I didn’t know the name, he didn’t tell me and my mum had – my mum grew up in a family of secrets as I’ve said. One of the things that wasn’t secret was when her parents punished her or her brother and it was done publicly and the non-punished child would giggle and point at the one being punished.

And when Mum grew up, got her own family, she decided the punishments were going to be private because she didn’t want a rerun of what had happened in her world. Unfortunately she’d married a man who thought that all his Christmases had come at once with this rule and so punishments were private. And in 14 years of abuse nobody ever walked in on me and Dad, it’s a miracle. Nobody ever came in when he was hurting me. And yet this was - for many years this was a daily affair. But I couldn’t tell Mum, didn’t have the words.

G: And I know this is a challenging question to answer ‘cause your mum is actually listening to the livestream and watching the livestream -

J: Hi Mum.

G: Now I do want to make sure we’ve got time for questions because you said to me that it was very important to you that people got to ask questions. I’m just going to have a quick look at the time. We are almost out of time. I do want to say if anyone wants to ask questions – I am very strict about this – no disclosures, please, because we don’t want anybody re-traumatised and short questions that start with who, what, why, when, where, how. So does anyone want to ask Jeni a quick question? Anyone there? Anyone brave?

J: I don’t bite.

G: We are actually – I mean if no-one – oh yes, go ahead. And we’ve got Sonia, I think, coming with the – or Jane coming with the microphone just so people on the livestream and the recording can hear you.

A: You said that you wanted to kind of push away the [stigmatation] 59:01 of MPD. How do you feel about the way it’s represented in pop culture and that kind of stuff?

J: Yes, split. I’ve watched a lot of movies around MPD, I’ve watched the representations of people who actually have MPD so Sybil and Eve and Truddi Chase. And the movies get it wrong on so many levels. The vast majority of survivors with MPD are female, there are no female fictionalised stories for MPD. They are always men and serial killers. Okay, just to clarify, I’m a woman, I do not have a bunker under my rental house in which I am going to kidnap men although – doesn’t happen because if you have MPD as a result of serious abuse the likelihood that you wish to dish that on anybody other than your abuser is so remote as to be laughable. I don’t feel that I matter, I’m hardly going to go out and kidnap people and then murder them for the fact that they left me when leaving me is what I expect people to do. If you don’t matter you don’t even – we don’t even go down that way.

But there was a lady in Brisbane who actually had MPD and did actually kill a gentleman and when it came up she refused to use her MPD as an excuse or a get of jail free card. And they had a mental health hearing to see if she was actually allowed to do this and she said I have no intention of using this as an excuse. And she said the things that I’ve always felt, if the gob says it and the body done it I own it. Whereas if you watch pop culture it’s always abandoning responsibility, blaming somebody else. I only blame my dad for what he did and the consequences of what he did. I don’t go out and kill people because they look like my dad, because they might actually have been thinking about doing something my dad did. To me the whole way MPD is presented is lunacy, it’s more lunatic than we are.

G: We’re waiting for your screenplay, Jeni.

J: Only if I get to make sure it’s correct.

G: Yeah, that’s right. We won’t invite the lawyers. Has anyone else got a question? We are nearly out of time, maybe just one more? Yes, go ahead.

A: Hi, I’ve always wanted to know since talking to Symphony, have you ever thought rather than do a screenplay – as you know I work in the music industry – would you like to write a couple of songs or have you written a couple of songs not about what happened but more about the amazing survival that you’ve got? Like you know we’ve got a [Judas] 2:48 in common. Mine’s a little bit more real world and a bit more annoying than yours is, yours is fantastic -

J: Yours is sexy, mine is not. He’s a little boy.

G: Oh mine acts – so yeah, Yeah, that was my question.

J: I’ve never thought of doing that, I’ll be honest.

A: [unclear 3:09] ready to go.

G: Anyone got a guitar?

J: Drum kit. Yeah.

A: Song-writing is very healing, that’s what I’ve found so I’m just wondering what your thoughts were.

J: Music has been so important to me. Because Dad said he could read my mind I think in song lyrics. Even this evening most of what I’ve said has first come to my head as a song lyric which can be tricky. Even your [Judas] gets a couple of quotes in that one from Jesus –

A: [unclear 3:46].

J: So I think in song lyrics I associate so strongly with music. I have an alter named Gabrielle, she’s responsible for all this. She’s our lady, she’s absolutely stunning but she was born from the song lyrics of The Osmonds. So everything that they sang about their girl, how pretty she was, how understanding she was, how honest she was, that is what our Gabrielle took. It’s not like she created it, it’s we took that and gave it to Gabrielle to keep safe so when we’ve talked about - a number of times there’s been a question of how does MPD save your soul? This is how it does it. MPD or your alters find things that matter and they cut them out and they keep them safe. Gabrielle got to keep everything about being a woman, everything about being a girl that was pretty and dainty, the ballerina stuff, everything. Gabrielle holds the lot and finally after Dad was sent to prison for 45 years Gabrielle got to emerge, much like the butterfly and she took over and well this is the result.

Applause

G: Thank you. Alright we are going to leave it there even though I could talk to you for another five hours. Thank you so much for coming tonight and thank you for your honesty and thank you for writing such an amazing book and thank you for making legal history.

J: Oh yeah, that was amazing.

S: Thank you. And thank you to Ginger and to Jeni for that really challenging and honest discussion, it was fabulous.

J: Thank you.

S: I’d like to thank you for coming tonight and –

End of recording

Content warning: This video includes discussion about child sexual abuse, domestic abuse, death threats and mental health issues. The video also contains some course language.

In a discussion facilitated by Ginger Gorman, Jeni Haynes talks about her book, The Girl in the Green Dress.

Described as 'unforgettable', The Girl in the Green Dress is a memoir from a woman who refused to be silenced. After enduring many years of abuse, Jeni fought to create a life for herself and bring her father to justice in a history-making ruling. In speaking out, Jeni's courage would see many understand Multiple Personality Disorder (MPD) for the first time.

About the book

An intelligent, poised woman, Jeni Haynes sat in court and listened as the man who had abused her from birth, a man who should have been her protector, a man who terrified her, was jailed for a non-parole period of 33 years. The man was her father.

The fact Jeni survived is testament to the extraordinary strength of her mind. What saved her was the process of dissociation – Multiple Personality Disorder (MPD) or Dissociative Identity Disorder (DID) – a defence mechanism that saw Jeni create over 2,500 separate personalities, or alters, who protected her as best they could from the trauma.

With the support of her psychiatrist Dr George Blair-West, Jeni fought to create a life for herself and bring her father to justice.

About Jeni Haynes

Dr Jennifer Haynes grew up in Greenacre in Sydney's western suburbs. After enduring horrific abuse, Jeni fought for years to bring her father before the courts to face justice for what he had done. In doing so, she created legal history. Jeni spent 18 years at university, graduating with a degree in psychology, masters in legal studies and criminal justice as well as a PhD focusing on victims of crime.

About Ginger Gorman

Ginger Gorman is an award-winning print and radio journalist based in the Australian Capital Territory. She is also a 2006 World Press Institute Fellow. Her freelance work has been published in print and online in publications such as news.com.au, The Huffington Post, The Guardian, The Age, Mamamia and the ABC’s Drum website. Her first book, Troll Hunting, was published in 2019.

---------------------------------------------------------

If you, or someone you know, have been affected by issues raised in this video help and support is available. For crisis support, contact Lifeline on 13 11 14, chat with them online at lifeline.org.au or text them on 0477 13 11 14. Lifeline services are available 24/7.