Spring has definitely sprung in Canberra and around Australia.

Many of us are spending more time enjoying plants in bloom, especially exotic bulbs. It is also an excellent time to celebrate our spectacular native flowers.

This blog is about two of the earliest English publications to feature Australian flowers.

Both are, perhaps, a little overlooked today, in favour of early watercolour drawings either done from specimens or copied from other watercolours. The National Library of Australia holds significant collections of these watercolours from the late eighteenth century onwards.

Yet print–be it in book, journal or map format–was the primary way knowledge was widely circulated in the late eighteenth century. And at the time, the printed version was arguably more important than the preparatory drawing or watercolour.

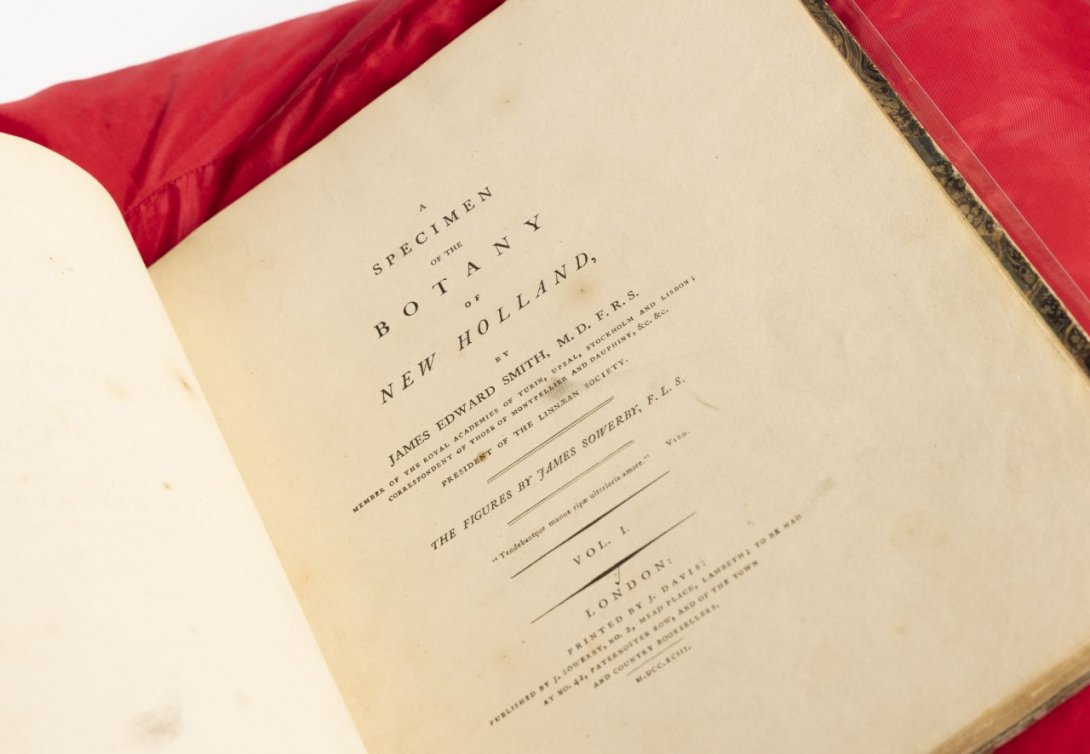

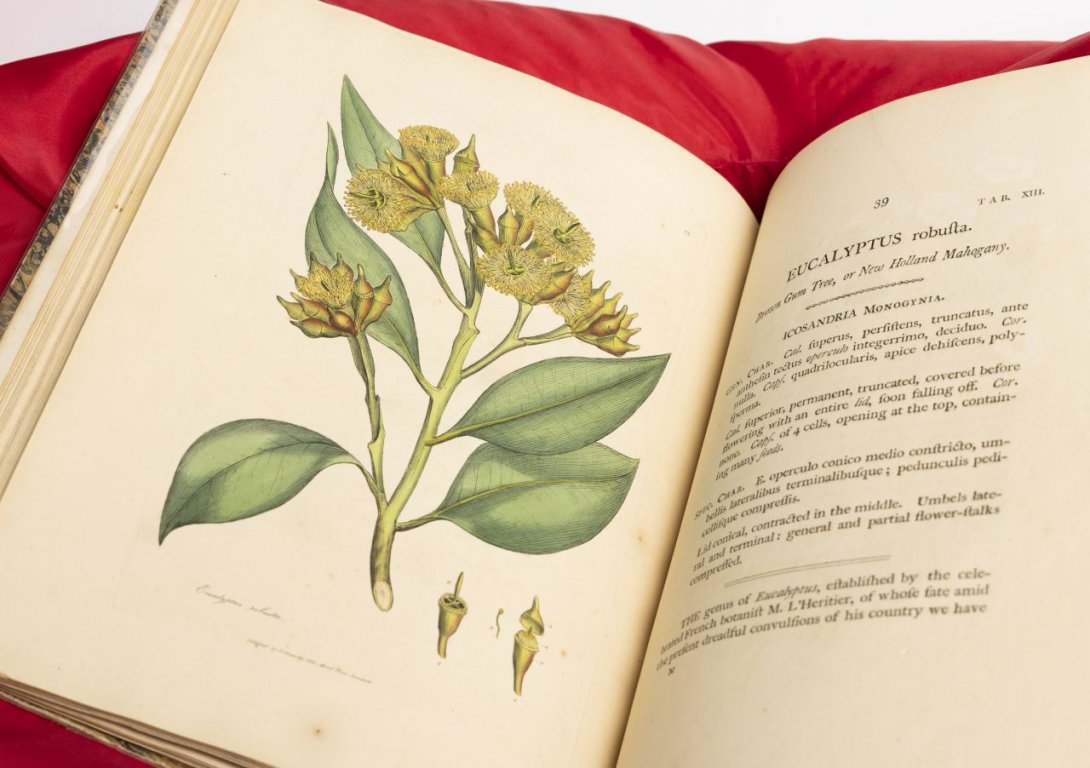

One is the first printed book just on Australian flowers: James Edward Smith, A Specimen of the Botany of New Holland...The Figures by James Sowerby, F.L.S., vol. 1, London: Printed by J. Davis, Published by J. Sowerby, 1793.

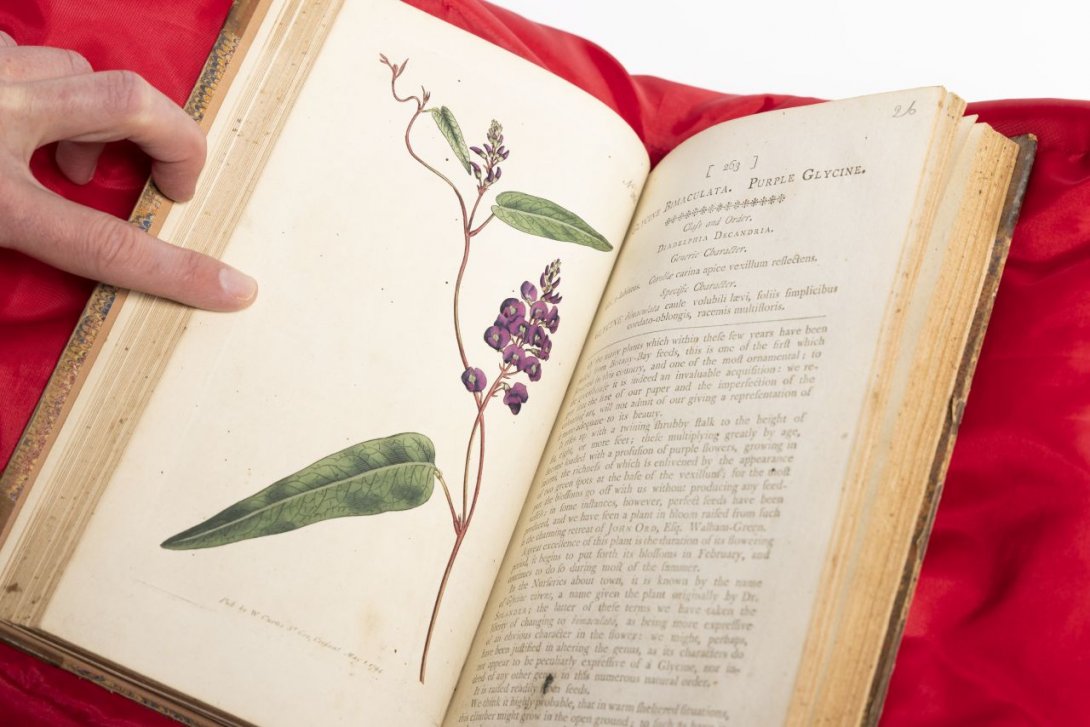

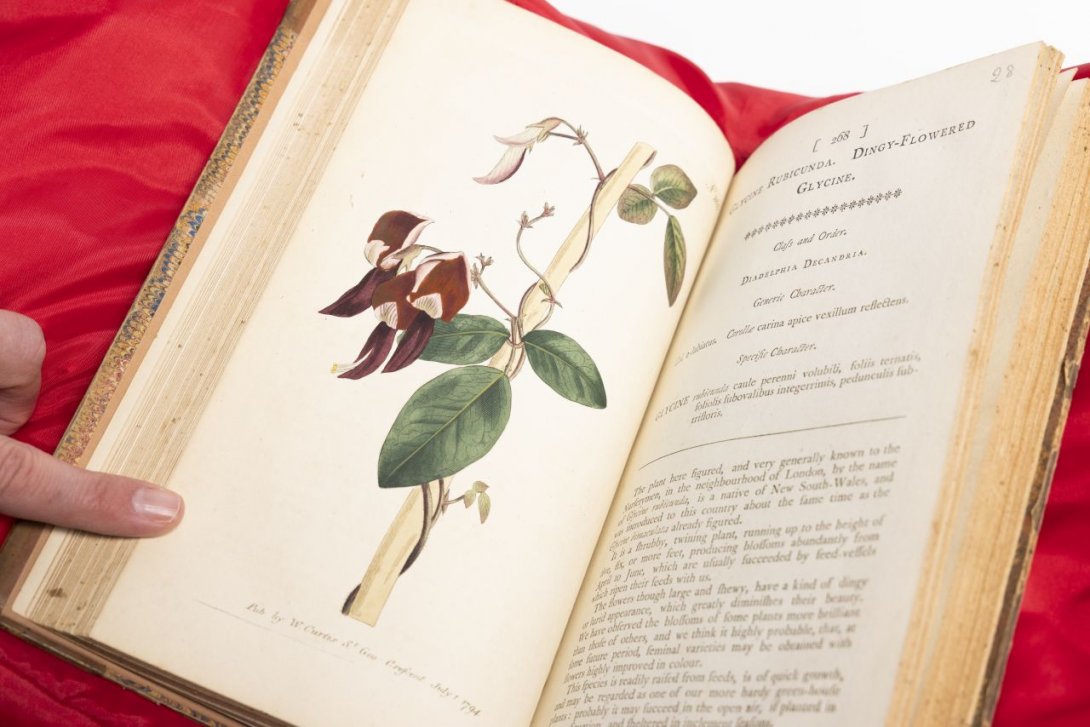

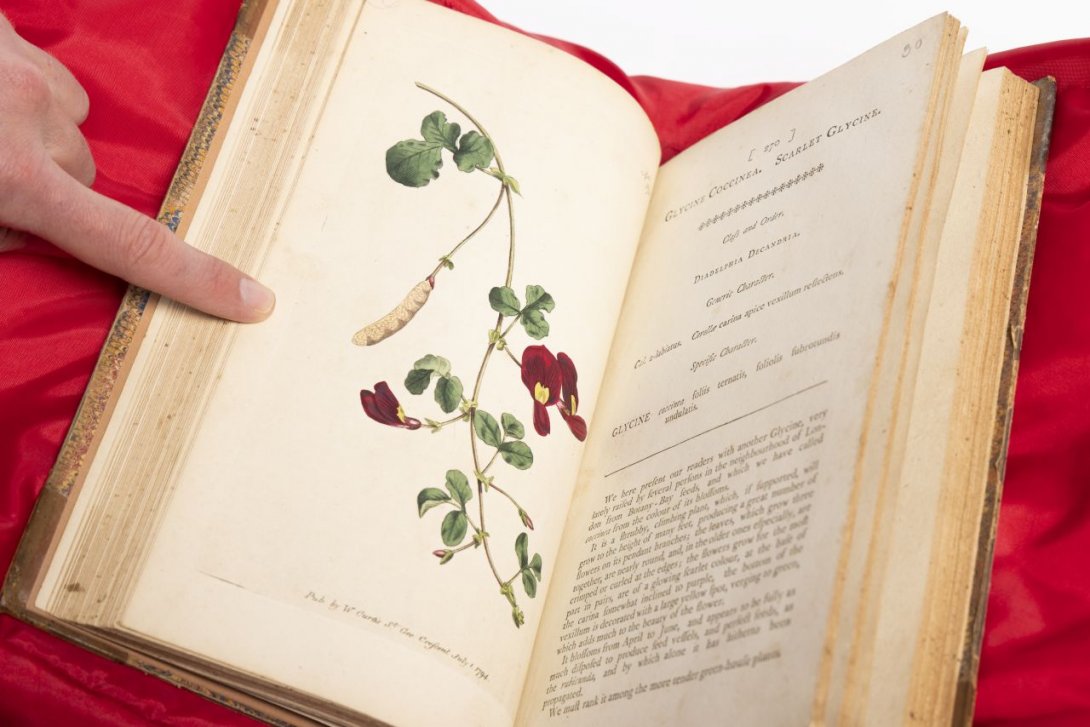

The second is Curtis’s Botanical Magazine, which featured Australian flowers from the early 1790s. Founded in 1787, it is the oldest botanical journal still published.

James Edward Smith, A Specimen of the Botany of New Holland (1793)

A Specimen of the Botany of New Holland was printed in London, conceived as the first in a two-volume series on botany. (A second volume did not eventuate.) The National Library of Australia holds four first editions, and numerous single plates. Interestingly the three books I could view, due to stack closures, are assembled slightly differently.

The author was the botanist and physician Sir James Edward Smith (1759–1828), who was at the forefront of botanical study in Britain for decades. In 1784, aged 25, Smith and his father acquired the papers, books and natural history collections of the great Swedish naturalist Carl Linnaeus (1707–1778), at a total cost of 1088 pounds. (Sir Joseph Banks, then President of the Royal Society of London, had declined to acquire them.) With others, Smith founded the Linnean Society of London in 1788, made his own collection and was the Society's President until his death in 1828. Smith and Linnaeus's collections are still held together today in Burlington House, Piccadilly, in London.

The driving force behind the book was the naturalist and collector Thomas Wilson, to whom the book was dedicated.

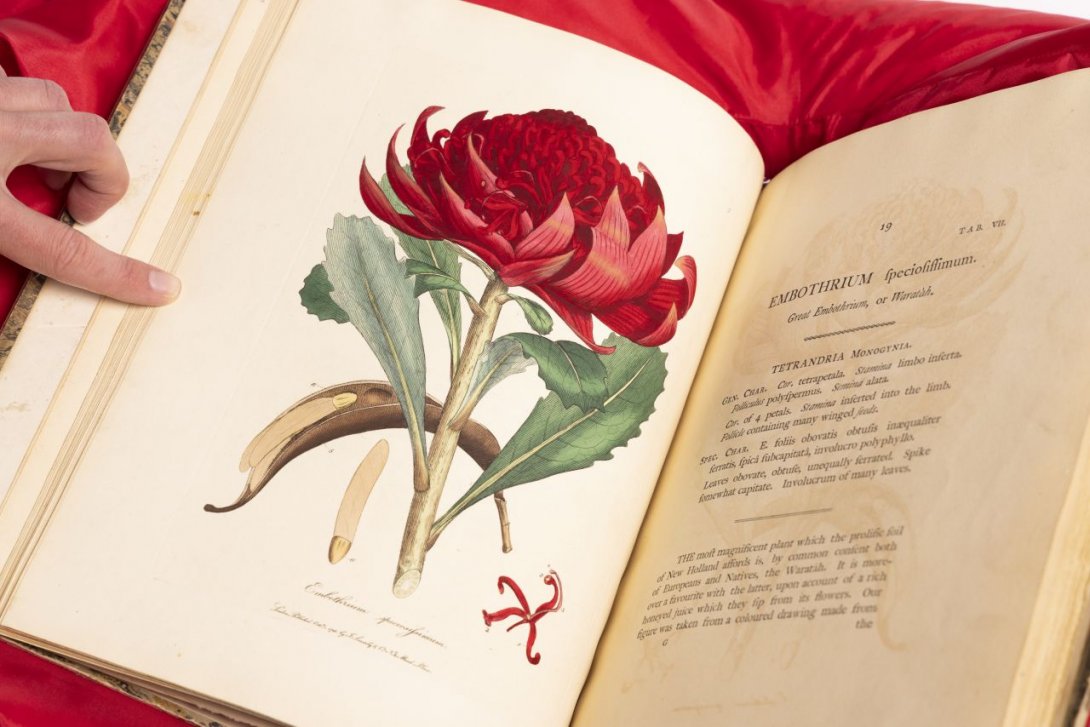

Many of the plates are splendid and, as the waratah above shows, have retained their colour for illustrations made about 230 years ago.

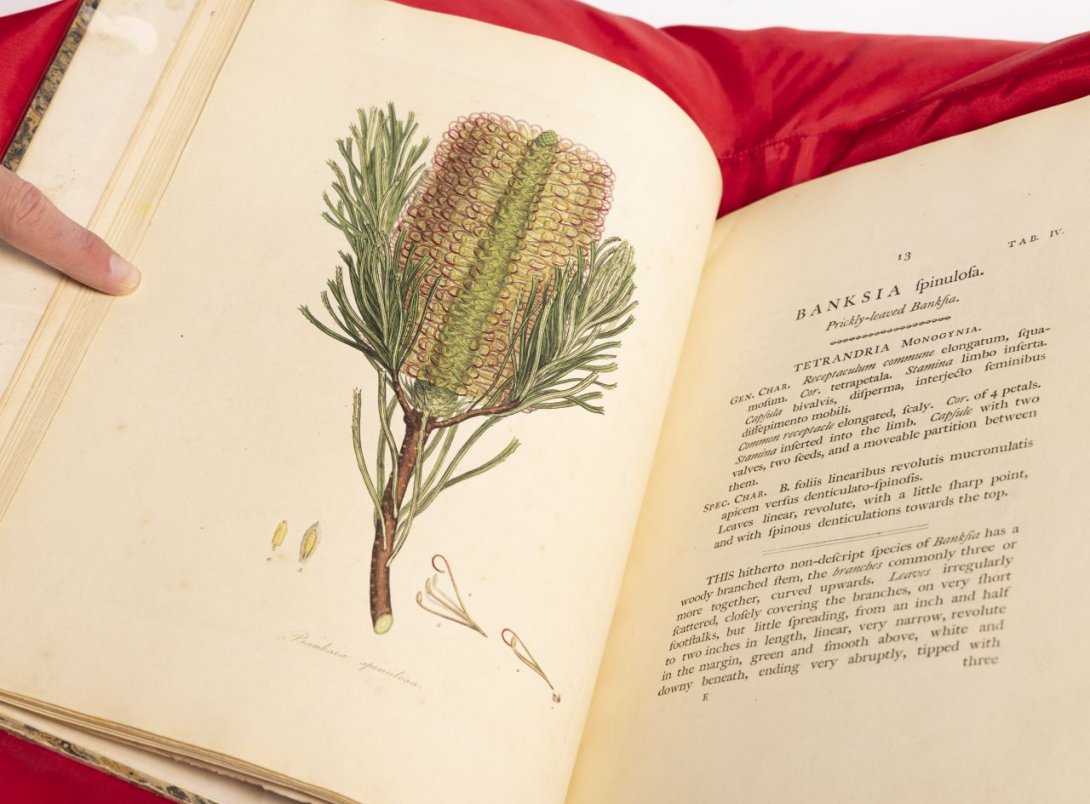

Each plate is a hand-coloured copperplate engraving. A copperplate was incised with a burin in reverse, inked and then printed onto paper, while the accompanying text was printed using metal type letterpress. The plates follow the format typical in scientific illustration of the time, with details of important parts of a plant to the side or bottom of the plate. These are numbered and named in an 'explanation' at the end of the text.

The artist was James Sowerby (1757–1822), with whom Smith collaborated on eight books, including English Botany (1790–1814) and Exotic Botany (1804–1805), both of which the Library holds. Trained at the Royal Academy, Sowerby came to specialise in botanical illustration and collecting natural history more broadly. He was savvy and well-connected in the scientific world. He was interested in colour, publishing A New Elucidation of Colours (1809), also held. An early trade card (from 1786) is at the British Museum; his correspondence to and from James Edward Smith has been digitised by the Linnean Society and his archives are at the Natural History Museum, London.

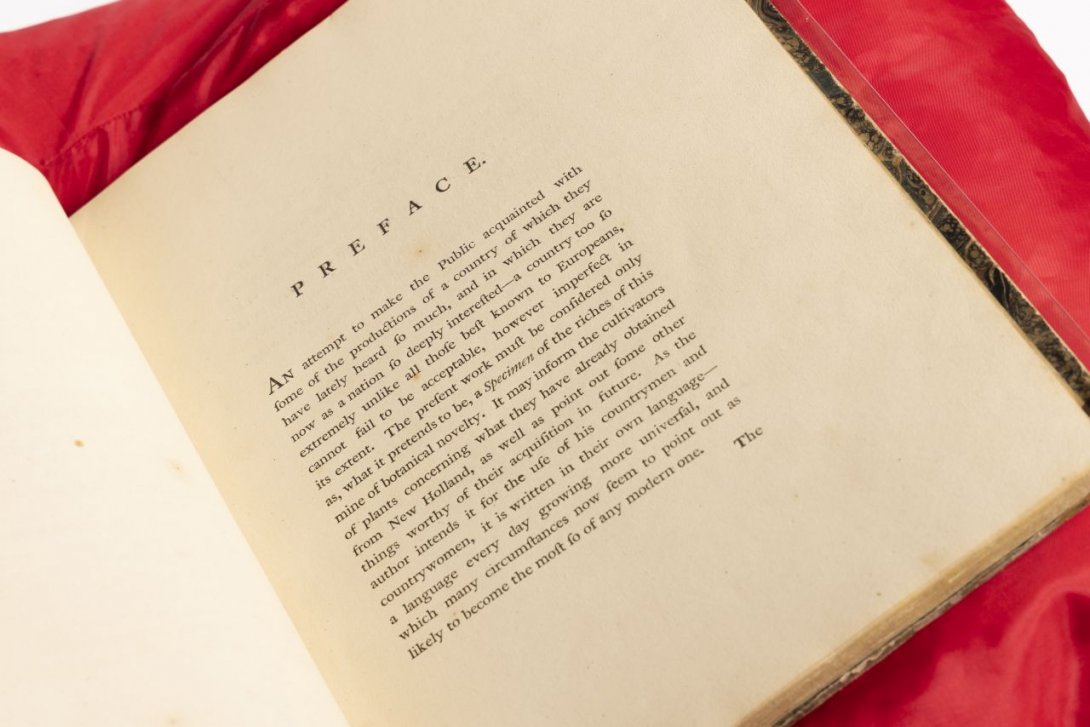

The book’s preface–succinct at only two paragraphs–serves as an introduction. Today, we would say it manages expectations as to the book's scope, and suggests how it may prove useful. He has written it for a general audience, not just a scientific one:

An attempt to make the Public acquainted with some of the productions of a country of which they have lately heard so much, and in which they are now as a nation so deeply interested–a country too so extremely unlike all those best known to Europeans cannot fail to be acceptable, however imperfect in its extent. The present work must be considered only as, what it pretends to be, a Specimen of the riches of this mine of botanical novelty. It may inform the cultivators of plants concerning what they have already obtained from New Holland, as well as point out some other things worthy of their acquisition in future. As the author intends it for the use of his countrymen and countrywomen, it is written in their own language–a language every day growing more universal...

The second paragraph specifies what informed the plates:

The figures are taken from coloured drawings, made on the spot, and communicated to Mr. Wilson by John White Esq. Surgeon General to the Colony, along with a most copious and finely-preserved collection of dried specimens, with which the drawings have in every case been carefully compared.

December 1793

First Fleet Surgeon John White sent back some of the earliest Australian specimens to London in late 1788, and published his Journal of a voyage to New South Wales in 1790. (See this blog for more about the Library's holdings relating to it.)

Australian plants presented a problem of classification for European botanists, being both baffling and an embarrassment of riches, with an ever-shifting body of evidence. Smith addresses this in the text accompanying the third plate:

When a botanist first enters on the investigation of so remote a country as New Holland, he finds himself as it were in a new world. He can scarcely meet with any certain fixed points from whence to draw his analogies; and even those that appear most promising, are frequently in danger of misleading, instead of informing him. Whole tribes of plants, which at first sight seem familiar to his acquaintance, as occupying links in Nature's chain, on which he has been accustomed to depend, prove, on a nearer examination, total strangers, with other configurations, other œconomy and other qualities; not only all the species that present themselves are new, but most of the genera, and even natural orders.

16 Australian plants feature in this thin, beautiful, book. Each plant has a title, scientific name and description, followed by a short essay.

For the waratah, the essay begins:

The most magnificent plant which the prolific soil of New Holland affords is, by common consent ... the Waratah.

Smith says it was a favourite of Australia's First Nations people

upon account of a rich honeyed juice which they sip from its flowers.

Though not done from life, it drew on a watercolour done from life, and was compared with a specimen sent by John White.

Our figure was taken from a coloured drawing made from the wild plant, compared with very fine dried specimens sent by Mr. White.

At the time of publication, waratahs were difficult to propagate.

Only one garden in Europe, we believe, can boast the possession of this rarity, that of the Dowager Lady de Clifford, at Nyn Hall, near Barnet, who received living plants from Sidney Cove, which have not yet flowered. The seeds brought to this country have never vegetated.

For the banksia, it is clear that Smith was realising there were numerous varieties. He describes it at length, including:

The structure of the flower is well expressed in the annexed plate. We suspect the fruit figured in Mr. White's Voyage, page 225, fig.1, may belong to this species, but we have no positive authority to assert it.

He says that the First Australians 'call it Wattangre'.

The book devotes six pages of text to eucalypts. He refers to French botanist Charles-Louis L'Heritier de Brutelle (1746–1800), whose Sertum Anglicum, seu Plantae rariores quae in hortis juxta Londinium (1788–1792), was the first European publication to describe the eucalyptus. Smith's comments about the Frenchman's whereabouts remind us that this was the time of the French Revolution.

The genus of Eucalyptus, established by the celebrated French botanist M. L'Heritier, of whose fate amid the present dreadful convulsions of his country we have for some time been ignorant, was first published in the Hortus Kewensis, vol. 2. 157.

L'Heritier was assassinated in 1800, leaving a large herbarium.

Now to the magazine.

Botanical Magazine (from 1787)

Founded by the English apothecary and botanist William Curtis (1746–1799), Curtis's Botanical Magazine first appeared in 1787. It offered readers an affordable, yet beautiful, botanical publication in serial form. In size, it is quite small, and was therefore cheaper to produce. And it sold very well. In its early years, William Curtis wrote the text. The first plate, an iris, was indeed the work of James Sowerby, Curtis being one of his early patrons. Sowerby soon departed the magazine and the prolific, younger artist Sydenham Edwards (1768–1819) took over. An Australian wattle, one of the earliest plants to bloom in an Australian Spring, appeared in the magazine in 1791. Unlike Smith and Sowerby's A Specimen of the Botany of New Holland (1793), the Australian plants illustrated in the journal were mostly plants grown in England from seed.

The Library holds 11 rather curious, bound volumes and one box of unbound copies of the Botanical Magazine (Call number RB MOD 1263). They date from the late 1780s to the mid-19th century. In some cases, the plates follow no particular order, one volume including plates from other publications. It makes the set a rather unique, if idiosyncratic collection. They were acquired from the collection of George Cowlishaw (1901–1983), among 1809 books and serials about botanical and agricultural subjects. (See the Cowlishaw Collection guide.)

Despite their arrangement, the volumes include most of the early illustrations of Australian plants. Here are several:

Of the many plants which within these few years have been raised from Botany-Bay seeds, this is one of the first which flowered in this country, and one of the most ornamental; to the greenhouse it is indeed an invaluable acquisition: we regret that the size of our paper and the perfection of the colouring art, will not admit of our giving a representation of it more adequate to its beauty.

The plant here figured, and very generally known to the Nurserymen, in the neighbourhood of London, by the name of Glycine rubicunda, is a native of New South-Wales, and was introduced to this country about the same time as the Glycine bimaculata already figured.

It is a shrubby, twining plant, running up to the height of five, six, or more feet, producing blossoms abundantly from April to June, which are usually succeeded by seed-vessels which ripen their seeds with us.

The flowers though large and shewy, have a kind of dingy or lurid appearance, which greatly diminishes their beauty. We have observed the blossoms of some plants more brilliant than those of others, and we think it highly probable, that, at some future period, seminal varieties may be obtained with flowers highly improved in colour.

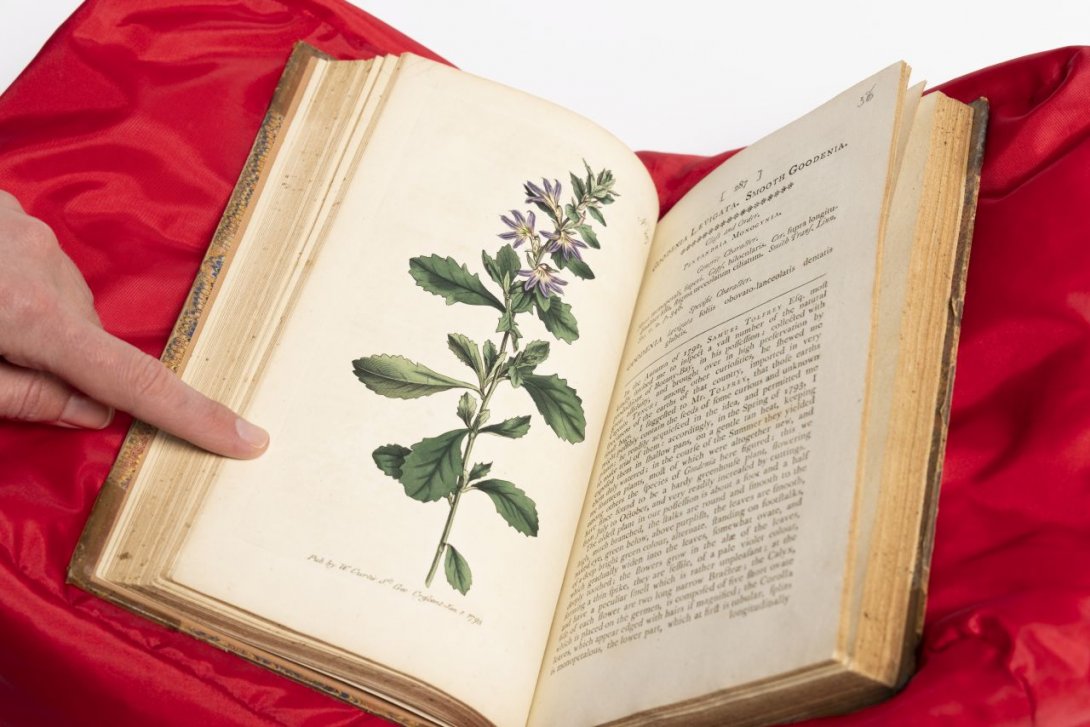

In the Autumn of 1792, SAMUEL TOLFREY Esq. most kindly invited me to inspect a vast number of the natural productions of Botany-Bay, in his possession; collected with great assiduity, and brought over in high preservation by Captain TENCH; among other curiosities, he shewed me specimens of the earths of that country, imported in very small bags. I suggested to Mr. TOLFREY, that those earths might possibly contain the seeds of some curious and unknown plants; he readily acquiesced in the idea, and permitted me to make trial of them: accordingly, in the Spring of 1793. I exposed them in shallow pans, on a gentle tan heat, keeping them duly watered; in the course of the Summer they yielded me fourteen plants, most of which were altogether new, and among others the species of Goodenia here figured; this we have since found to be a hardy greenhouse plant, flowering from July to October, and very readily increased by cuttings.

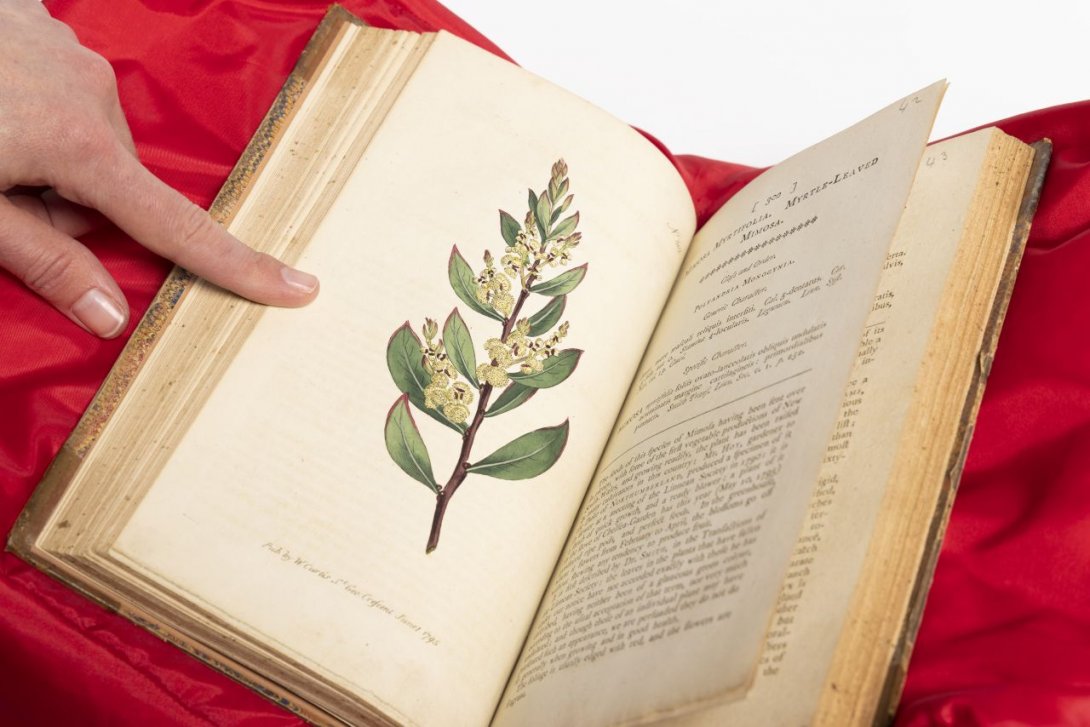

The seeds of this species of Mimosa having been sent over in plenty, with some of the first vegetable productions of New South-Wales, and growing readily, the plant has been raised by many cultivators in this country; Mr. HOY, gardener to the Duke of NORTHUMBERLAND, produced a specimen of it in flower at a meeting of the Linnean Society in 1790; it is a shrub of quick growth, and a ready blower: a plant of it in the stove of Chelsea-Garden has this year (May 10, 1795) produced ripe pods, and perfect seeds. In the greenhouse, where it flowers from February to April, the blossoms go off without shewing any tendency to produce fruit.

It is first described by Dr. Smith, in the Transactions of the Linnean Society; the leaves in the plants that have fallen under our notice have not accorded exactly with those he has described, having neither been a glaucous green colour, according to the usual acceptation of that term, nor very much undulated; and though those of an individual plant may have presented such an appearance, we are persuaded they do not do so generally when growing and in good health.

The National Library of Australia's rare book collections are very strong on Australian botany from the 1790s. This is just a taste. Search our Collections online or join your National Library today.

Selected Further Reading:

- Matthew Fishburn, ‘Thomas Wilson Esq and the Natural History Collections of First Fleet Surgeon John White’, Journal of the Royal Australian Historical Society, vol. 109, no.1, pp.79–100.

- Paul Henderson, James Sowerby: the Enlightenment’s Natural Historian, Richmond, Surrey: Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew, 2015.

Dr Susannah Helman is Rare Books and Music Curator at the National Library of Australia.