**FIRST NATIONS PEOPLES ARE ADVISED THAT THIS BLOG POST MAY CONTAIN CONTENT THAT MAY BE CONSIDERED CULTURALLY SENSITIVE.**

Bess Moylan is a Spatial Scientist and an Honorary Associate at the School of Geosciences, University of Sydney. During her time at the National Library of Australia as the 2019 Curatorial Research Fellow, supported by Patrons and Supporters of the Treasures Gallery Access Program, Bess has been investigating how a better understanding of historical maps can support research into Aboriginal cultural landscapes.

At first glance Australian historical maps tell stories of exploration and land development, but what happens when we take a look from another perspective? What other stories can we find if we decolonise historical maps?

Historical maps can be useful when researching Aboriginal cultural landscapes and they can help researchers develop family histories, trace trading paths and Songlines, investigate traditional fire management regimes, reconstruct land use patterns, and explore local languages.

While historical maps may contain Aboriginal cultural landscape information – these maps are not always easy to find, and older catalogue descriptions do not truly reflect the contents of the map.

Here are some examples of maps in the collection and how the decolonisation process might work.

Hidden in plain sight

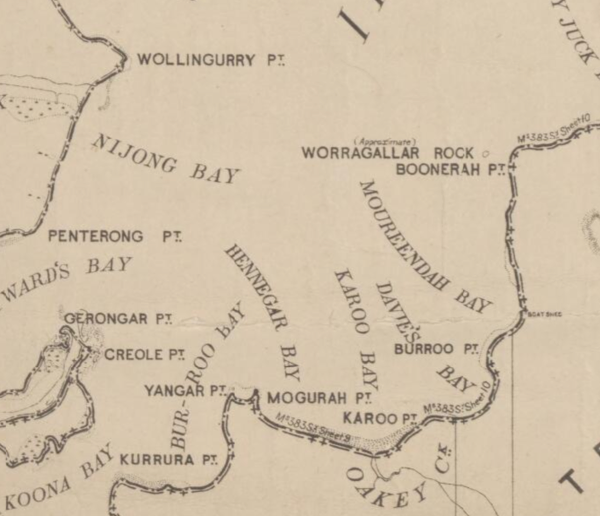

Cadastral maps were used to communicate European based land ownership systems. If viewed from an alternative perspective the Aboriginal cultural landscape can be seen. Look at this extract from the 1897 Parish Map of Wollongong. Look closely at the placenames.

Extract from Parish of Wollongong, County of Camden: Land District of Wollongong Eastern Division N.S.W. / compiled, drawn and printed at the Department of Lands, Sydney N.S.W. April 1897 https://nla.gov.au/nla.obj-232428357/view

This parish map, like most in Australia, contains many placenames derived from Aboriginal languages. The catalogue record doesn’t mention placenames – its description is purely administrative. With 2019 being the UN International year of indigenous languages it is timely to look at how these placenames are recognised in historical maps. Acknowledging these placenames in the catalogue description could be a way to recognise the long occupation of land prior to European domination.

Cadastral maps often also contain information about the land use, vegetation patterns, Aboriginal pathways, and hydrological structure before the introduction of European agricultural methods. The Library develops research guides for selected topics, and a research guide on Aboriginal cultural landscape features in Cadastral maps could increase the use of these maps for research purposes.

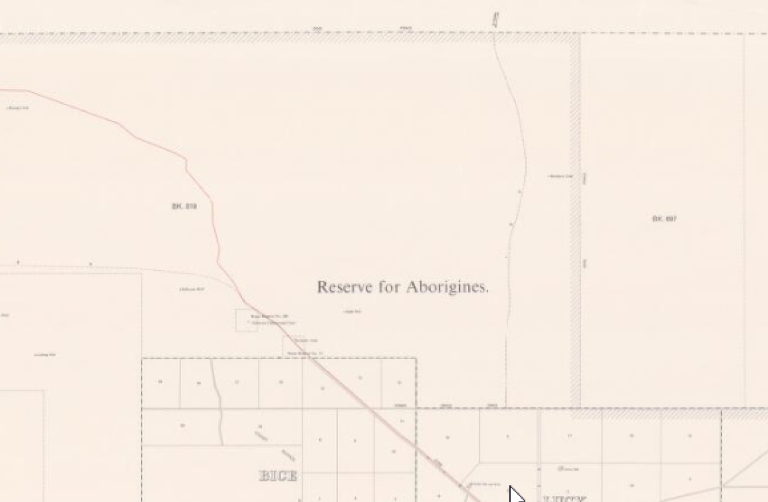

Post-colonial Aboriginal landscapes can also be reflected in Cadastral maps, and an important feature in this landscape are Aboriginal missions or reserves. These sites are not always easy to locate as they can change location and are sometimes ephemeral in nature. The County of Hopetoun map contains a significant reference to an Aboriginal cultural landscape feature, noted as ‘Reserved for Aborigines’.

County of Hopetoun compiled in the Office of the Surveyor General 1964 https://nla.gov.au/nla.obj-878899237/view

As an older catalogue record, the notes section only mentions the name of the map. Updating the catalogue record to include a reference to the reserve would make its location easier to find.

Marks on the Explorer’s maps

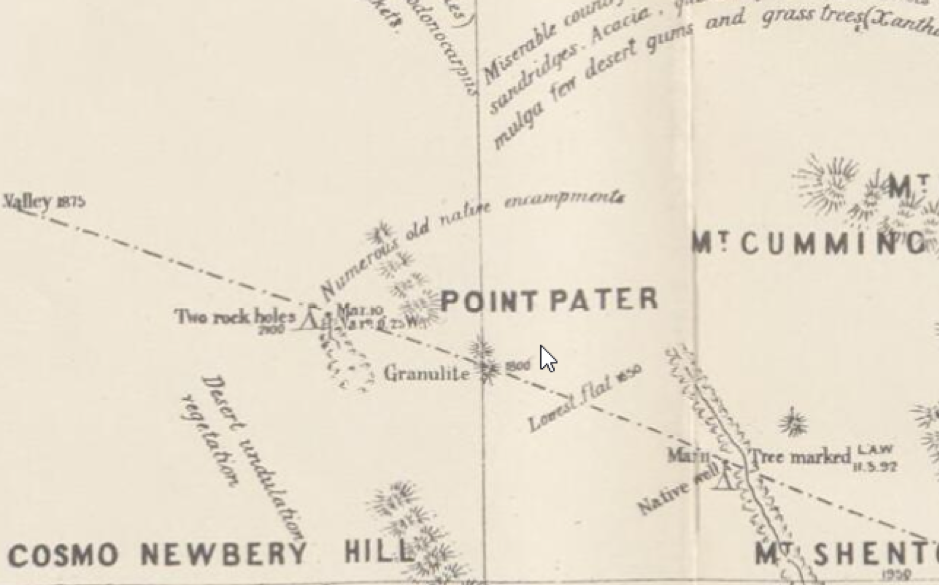

A study of the Lindsay and Wells map reveals references to ‘Numerous old native encampments’ and ‘Native wells’. The catalogue record for this map does not describe these as Aboriginal cultural landscape features although they are clearly an important feature on the map.

Map showing the explorations and discoveries in South Australia and Western Australia made by the Elder Scientific Exploring Expedition 1892? Compiled and drawn by D. Lindsay and L.A. Wells https://catalogue.nla.gov.au/Record/3891769

Subject headings primarily used by the National Library of Australia have been developed by the Library of Congress. Unsurprisingly, these headings do not reflect the Australian Aboriginal experience.

The Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Straits Islander Studies (AIATSIS) have developed subject headings that reflect their interests– and the National Library of Australia has recently begun adopting these.

Additional subject headings that include these features could make them easier to find, and better reflect the broader contents of the Lindsay and Wells map. The addition of AIATSIS subject headings to consider include:

- Water supply - Waterholes and rockpools

- Water supply - Wells and bores

- Settlement and contacts - Explorers - Aboriginal guides

- Habitation - Camps

Where we lived

Aerial photos are an excellent base to understand the spatial context of stories embedded in the landscape. They are useful to identify where people lived and travelled, explore vegetation patterns, record family histories, and create map biographies.

Listen to Yanti exploring the Library’s Aerial Photography collection for a richer understanding of her country’s past.

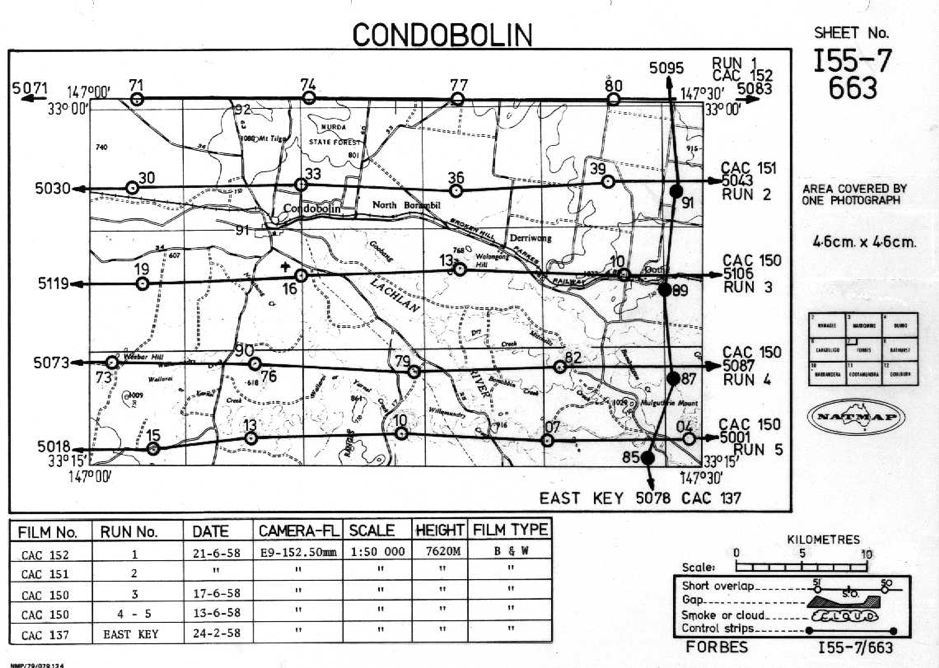

Below is an example of 1958 aerial photography of Condobolin. Three Aboriginal reserves have been identified in this photo.

Condobolin 1958 - MAP Aerial Photograph Collection I 55 7 663 – Run 3 Photo 5117

Locating the photo for a place generally means finding the flight photo index, and then identifying the run and photo number in the index to the corresponding place of interest.

Condobolin [cartographic material] 1958 MAP Aerial Photograph Collection I 55 7 663 https://nla.gov.au/nla.cat-vn4329312

A research guide explaining how to find aerial photos and interpret them for Aboriginal cultural landscape research will give broader access to this powerful mapping source.

Other map types being investigated

- Maps in the collections of anthropologists (for example Daisy Bates). Linking the maps to their field work note books and adopting the Austlang (Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander languages) classification codes.

- Travelling stock route maps. Notes about travelling stock routes and their links to Aboriginal pathways: https://catalogue.nla.gov.au/Record/3995059

- Pastoral run maps that contain references to properties where Aboriginal families worked. For an example see: https://catalogue.nla.gov.au/Record/4979814

- Historical topographic maps. Another massive map series that contains historical landscape information and placenames. For example Koonibba Aboriginal community: https://catalogue.nla.gov.au/Record/1760490

- Maps used in Native title claims – for example Mabo Native Title Case: https://nla.gov.au/nla.obj-224080958/view

Next Steps

Bruce Pascoe (Dark Emu) and Bill Gamage (The Biggest Estate on Earth) have recently brought long overdue public attention to the significance of historical records in researching Aboriginal cultural landscapes. Maps are part of these records, and the next step is to make those historical records accessible to help understand the past, and plan for the future.