Australia’s proximity to Antarctica means that its features and history are well recorded within the National Library, Canberra. In photographs, maps, drawings, books, manuscripts and commemorative items we can see our history entwined with the hostile southernmost landmass and nature reserve. Antarctica is the fifth largest continent, it is roughly twice the size of Australia, and its remoteness and extremity has exerted a fascination for many readers of exploration narratives and for antiquarian collectors, such as Rex Nan Kivell. Those of you who have visited Hobart may well have seen the Government’s Aurora Australis, moored at Prince’s Wharf. The striking orange research vessel is soon to be replaced with the Nuyina, a new icebreaker whose name means 'southern lights' in palawa kani, the Tasmanian Aboriginal language.

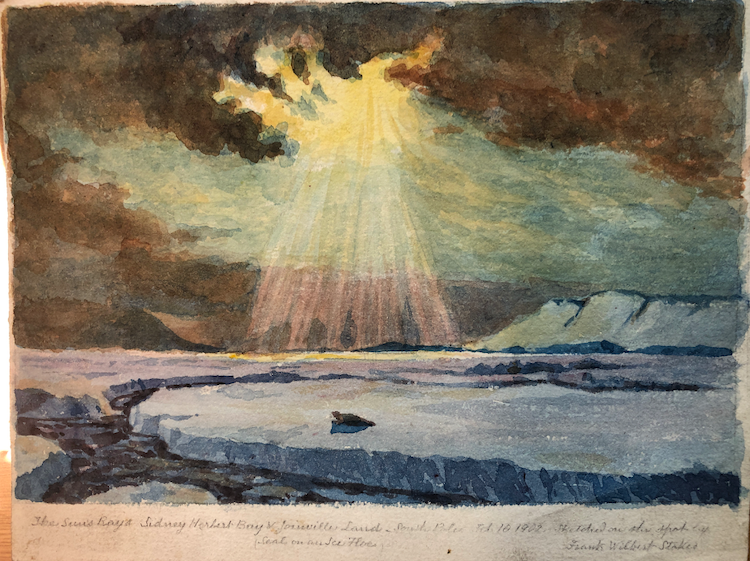

Frank Wilbert Stokes, The Sun's Rays, Sidney Herbert Bay & Joinville Land, South Pole, Feb. 10, 1902, nla.cat-vn415266

Before Nuyina sails to Antarctica this year, there has been speculation about the region for centuries, and later investigation and documentation by explorers, scientists and artists. The early visitors were a hardy bunch and lacked the luxuries, the puffer jackets, thermals and good food that voyagers take for granted today. James Cook’s epic second voyage sailed close on three occasions between 1772 and 1775 in the Austral summer and hardworking artist William Hodges painted the landmass from afar, but it was not to be until 1820 that humans first sighted the continent properly. Whether it was the Russian Bellinghausen expedition, which may have sighted continental ice in late January 1820, or Edward Bransfield, a Royal Naval officer who saw land a few days later, or the American sealer Nathaniel Palmer, who saw land in November that year, the continent awaited serious investigation for almost a century.

Otto Nordenskjöld, Antarctic trapped in pack ice, in The Siege of the South Pole by Hugh Robert Mill (London: Alston Rivers Ltd, 1905), nla.cat-vn485111

The visit of the privately funded Swedish Antarctic Expedition, led by Otto Nordenskjöld in 1902, led to the first depictions painted on the continent itself. The accompanying artist was American-born painter Frank Wilbert Stokes and one of his small watercolours, ‘The sun’s rays, Sidney Herbert Bay & Joinville Land, South Pole, Feb.10, 1902’ was acquired by the prolific collector Rex Nan Kivell in his lengthy acquisition odyssey. This dramatic scene captures the fall of golden light emanating from a darkening sky as it focuses our attention on a shadowed, plump seal resting on an icefloe. Stokes wrote later of just such a seal, ‘it awkwardly humped and wriggled over the rocks a few yards past our feet, where it lay down and slept. The seals were entirely unaware of the presence of deadly enemies. The sensation that such a scene produces upon the mind is indeed very strange; the pathos of it is disquieting.’ Yet another Antarctic experience to be absorbed and weighed by the lonely visitor, along with the more extreme sensations of subzero temperatures, hypothermia, windburn, frostbite, trench foot, broken bones, physical exhaustion, snow blindness, sunburn and psychological disturbances. After completing his watercolour, Stokes wrote in pencil on the sheet of card, ‘Sketched on the spot’, as if to add veracity to the scene and to signal his brief presence there.

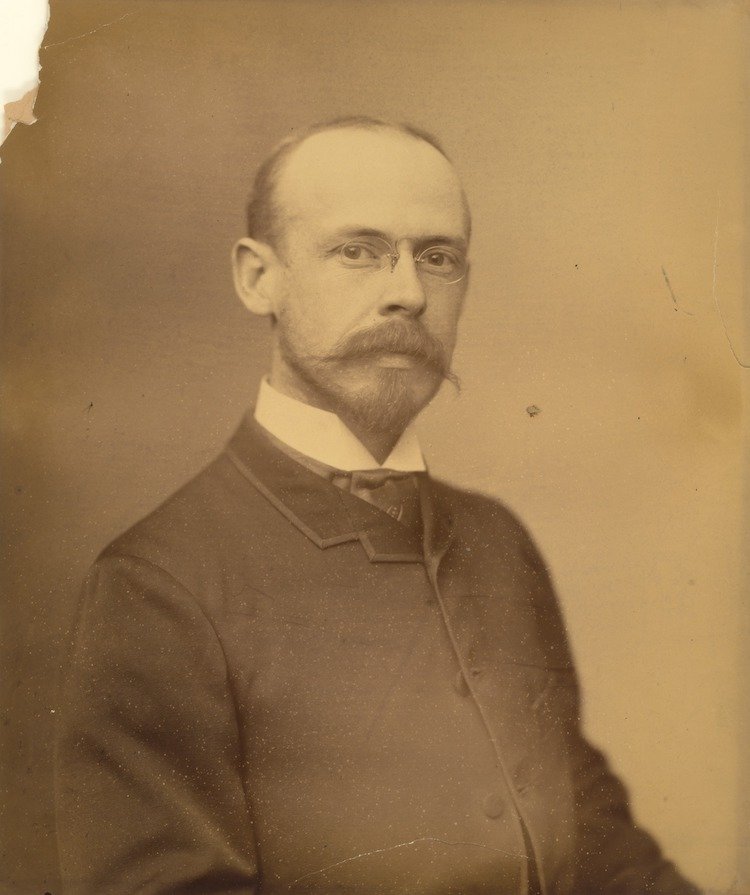

Stokes was born in Nashville, Tennessee in 1858 and had a lengthy life, not dying until 1955, in New York. This is perhaps surprising, given his passionate interest in visiting the Arctic and Antarctic and he did come close to losing his life on a number of occasions. First studying under well-known American painter Thomas Eakins, at the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts, Stokes then spent nine years living in France and England and studied at the École des Beaux Arts with Jean Leon Gérôme and in other prominent schools with leading French painters at the helm. Stokes’ style was also clearly influenced by Impressionism and he painted en plein air where possible to capture the remarkable light effects as quickly as he could manage.

Portrait of Frank Wilbert Stokes, 1893, Smithsonian American Art Museum, Arthur Curtis James and Robert Curtis Ogden Memorial Collection, 1955.4.45

Stokes was clearly an intrepid soul, if not sometimes foolhardy. On his second Greenland expedition with Commodore Peary, in 1893-94, all members of the exploring party were restricted from moving more than a quarter of a mile from the camp. This stipulation was relaxed for the fearless painter who would explore up to five miles from camp in the Polar night, with or without moonlight, to create images later to be printed in Scribner’s Magazine, the first magazine to feature colour illustrations. What he might have done if he had encountered a polar bear or fallen into a crevasse, he doesn’t commit to paper. Working in his Greenland studio for 14 months he combatted the subzero temperatures by keeping his painting kit in a deerskin bag and mixing his paints with poppy seed oil and petrol to make them suppler and less likely to freeze. At one point, he even managed to paint outside when the temperature was 30 degrees below zero (Fahrenheit).

Stokes was not only an able painter and survivor of extreme climates, he also could marshall a powerful and colourful turn of phrase when it came to writing about his experiences in the Arctic and on his two Antarctic voyages. His descriptions of the light, colours and scenery in the Antarctic are painterly and evocative and make interesting reading while considering his watercolours. Stokes faced an interesting artistic conundrum: how to accurately paint the extraordinary light and polar scenes which had only been witnessed by a handful of people and then to see how such images would be received by viewers who had never seen anything like it before. How could they calibrate their perception of such images when there were no such colour images in existence? It remains to say that he appears to have created accurate images without lapsing into overt romanticism. Stokes was ambitious in documenting the almost fictive weather effects and the remarkable scenes and produced many watercolours, a challenging task in the prevailing conditions. Some made their way into oil paintings as well. The Smithsonian Museum of American Art in Washington has a large collection of Stokes’ work donated by the artist and known as ‘Arthur Curtis James and Robert Curtis Ogden Memorial Collection’.

To return to Stokes’ descriptive powers in prose, the following is an extended quote evoking the artist’s struggles in creating responses to the majesty and danger sailing near the Antarctic. His words are from the article, An artist in the Antarctic, which he penned in 1903 and published in The Century Magazine. The narrative was illustrated with a version of Stokes’ manuscript voyage map and four carefully chosen images. One of these was, “The Sun’s Rays, Sidney Herbert Bay and Joinville Land, February 10, 1902, 7 P.M.” If not the watercolour later collected by Nan Kivell, it must surely be a variant on it.

“… a heavy gale was blowing from the south, with thick fog and snow hiding everything but the stormy seas close at hand. The deck was slippery from seal-blubber and ice and snow. With a wind blowing twenty-one meters per second, [75 km/h] it required some agility to cross even the waist of the ship. Returning to the cabin and the sketch I was painting between the lurches and rolls of the vessel, I was called up on deck. After an acrobatic ascent of the companionway, I managed to open and close the door, and holding on to any projection that offered, looked around. Cockburn Island, to the left, was almost hidden in a deep atmospheric gray mauve, inclining to turquoise cobalt, the threatening cloud-masses almost one tone of warm gray underneath, a mountainous mass of purplish-gray cloud-legions of a cumulus character, with a single opening of rich golden mellow ocher light casting a faint glimmer over the iron-like, heavy, storm-swept, gray-green waves rolling in from Erebus and Terror Gulf. The blasts of wind howled through the rigging continually, and the waves struck us heavily. We were heaving to in the lee of Cape Seymour for safety. Now and then a ghost-like iceberg suddenly appeared through the driving fog and spume, calmly, majestically pursuing its course, unaffected by the rage of the elements, like some mighty spirit from another world. All night the vessel labored, and by February 10 we had lost a sail, and the sailors had frostbitten hands, but the storm had flown with its furies. The Antarctic was sheathed in ice. I was hard at work on deck sketching Terre Louis Philippe from Erebus and Terror Gulf, the first promontory to the left of Cape Gordon.”

Through this evocative passage, Stokes leads us to the day on which he painted the work now in the Library’s collection - 10 February 1902. The ‘rich golden mellow ocher light’ accords with the scene in the centrepiece of our watercolour. Stokes was fortunate to leave Antarctica aboard the Antarctica at the end of February, via the Falkland Islands, Valparaiso, Montevideo bound for the U.S.A. Unbeknownst to Stokes, when the ship returned to the Antarctic in order to pick up Captain Nordenskjöld and the rest of the exploring party it became trapped in the ice and finally crushed and sank. Another vessel had to pick them up after they had weathered a severe winter in their small hut, the main room of which was only 8 ft x 14 ft. They had survived burning seal blubber and rubber, coating everything inside the hut with a constant layer of white ash, something which no doubt would have thwarted Stokes’ painting progress had he chosen to stay there.

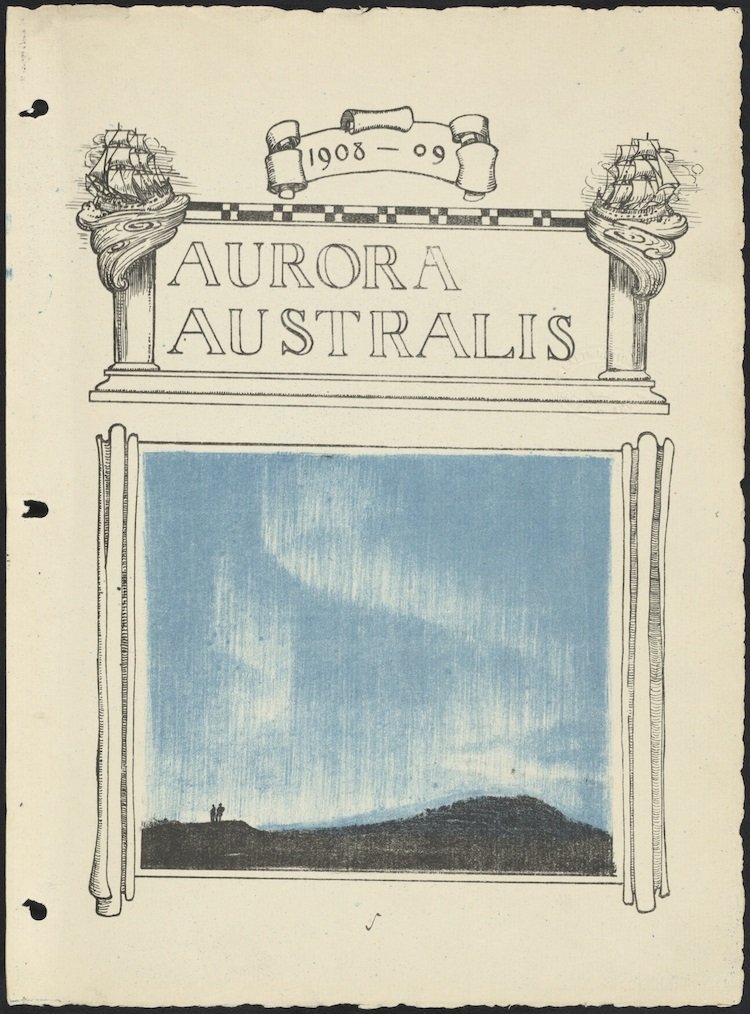

How Nan Kivell collected our important watercolour is, at this stage, unknown. However, his serious interest in Antarctic exploration can be attested to by the other important items in his expansive collection. He acquired a copy of the first book produced in the Antarctic, which is entitled Aurora Australis and was completely created at the base established by Shackleton and his men in 1908 and illustrated with lithographs and etchings by George Marston. One of our copies is digitised and can be accessed online.

George Marston, Ernest Henry Shackleton, Henry L. White & British Antarctic Expedition, Aurora australis, 1908, nla.cat-vn855596

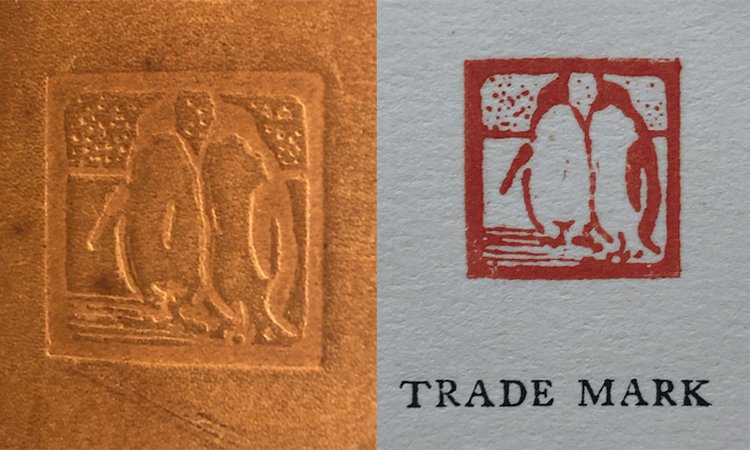

The boards (covers) of the books were made from wood at hand, mainly from packing crates and Nan Kivell’s copy (NK5544) was fabricated from a box stamped ‘butter’. The copies were proudly “Printed at the sign of ‘The Penguins’ by Joyce and Wild’ and they log the exact location, Latitude 77°.. 32’ South and 166 ° .. 12’ East, Antarctica. Additionally, and rather charmingly, they feature a ‘Trade Mark’ of two singing penguins on the title page and on the simple leather binding. Aurora Australis features in the first bibliography of Antarctica, which was painstakingly assembled by Sydney Spence, Nan Kivell’s bus-driving, book-collecting bibliographilic friend. The two men formed an unlikely friendship and worked together for decades, to assemble and then produce their epic, large format book, Portraits of the Famous & Infamous, (1975) which of course features Antarctic exploration and explorers.

George Marston, Ernest Henry Shackleton, Henry L. White & British Antarctic Expedition, Aurora australis (detail), 1908, nla.cat-vn855596

Nan Kivell also collected items related to the famous Scott Terra Nova Polar Expedition in 1910-13. As a youngster growing up in Christchurch he would have been one of the first to hear news of the deaths of the British explorers, who were robbed of their victory to be the first to reach the South Pole. The tragic news was relayed via New Zealand to England. The death of Scott and his team was a shock to the extended Empire. This early experience for the proto-collector may have encouraged him to later complete his extensive Australasian collection, which covered 500 years of global exploration focused on the Pacific, with objects from the frozen wastelands of Antarctica.

Metal plaque commemorating the Antarctic Expedition 1910-1912 with 4 views and portraits of Capt. Scott, Lady Scott and Peter and with the names of Wilson, Evans, Oates, Scott and Bowers, 1912, nla.cat-vn2048411

Within his collection is this rather small silvered bronze plaque featuring the main protagonists of the Scott expedition crafted into bas-relief images, derived from photographs. The plaque, poignantly, also features Kathleen, the sculptor artist wife of Scott and Peter, their only son who was just a toddler when his father died in 1912.

I can find very, very few extant examples of this touching, commemorative work; is it possible that Kathleen made it as a homage to her husband and his comrades and to a child who would grow up in the public eye without a father? More research may tell.