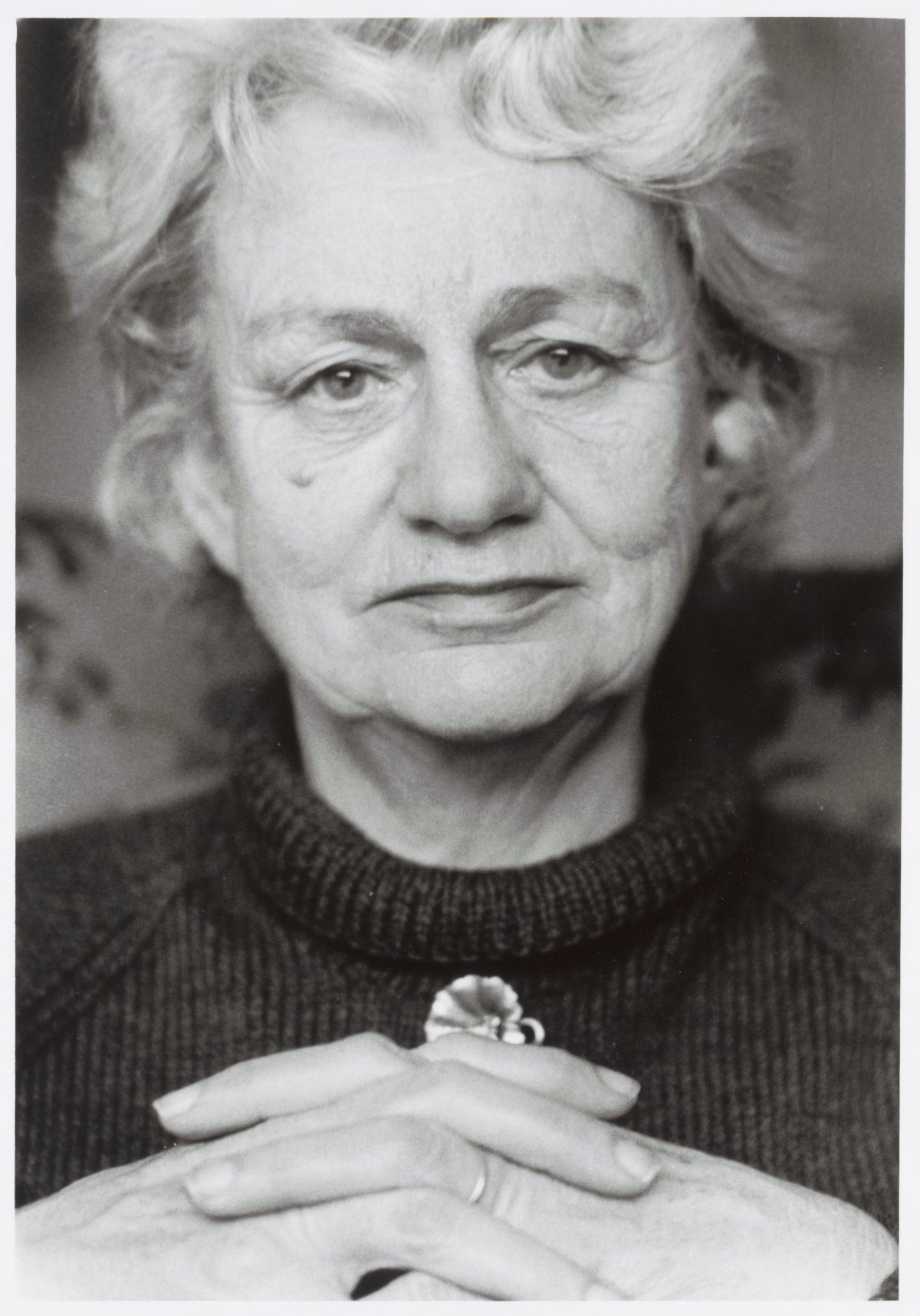

Mitelman, Jacqueline, 1952-. (1988). Portrait of Judith Wright [picture] / Jacqueline Mitelman. https://nla.gov.au/nla.obj-136372491

Australian News and Information Bureau. Portrait of Judith Wright [picture] / Australian News and Information Bureau. http://nla.gov.au/nla.obj-136839298

Milligan, Terry, 1941-. (1998). Portrait of Judith Wright, May 1998 [picture] / Terry Milligan. https://nla.gov.au/nla.obj-136416829

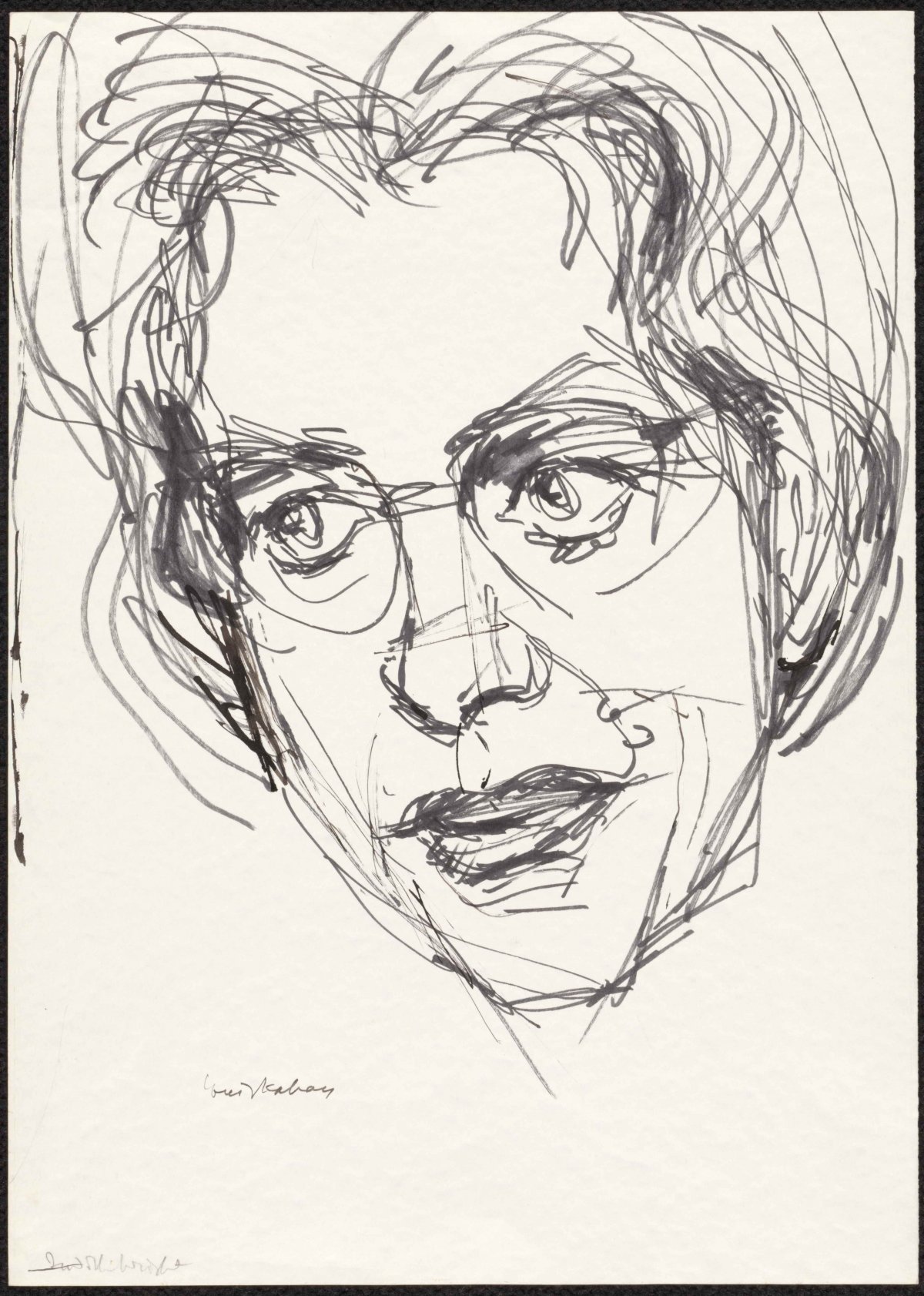

Kahan, Louis, 1905-2002. (1969). Portrait of Judith Wright [picture] / Louis Kahan. http://nla.gov.au/nla.obj-135084136

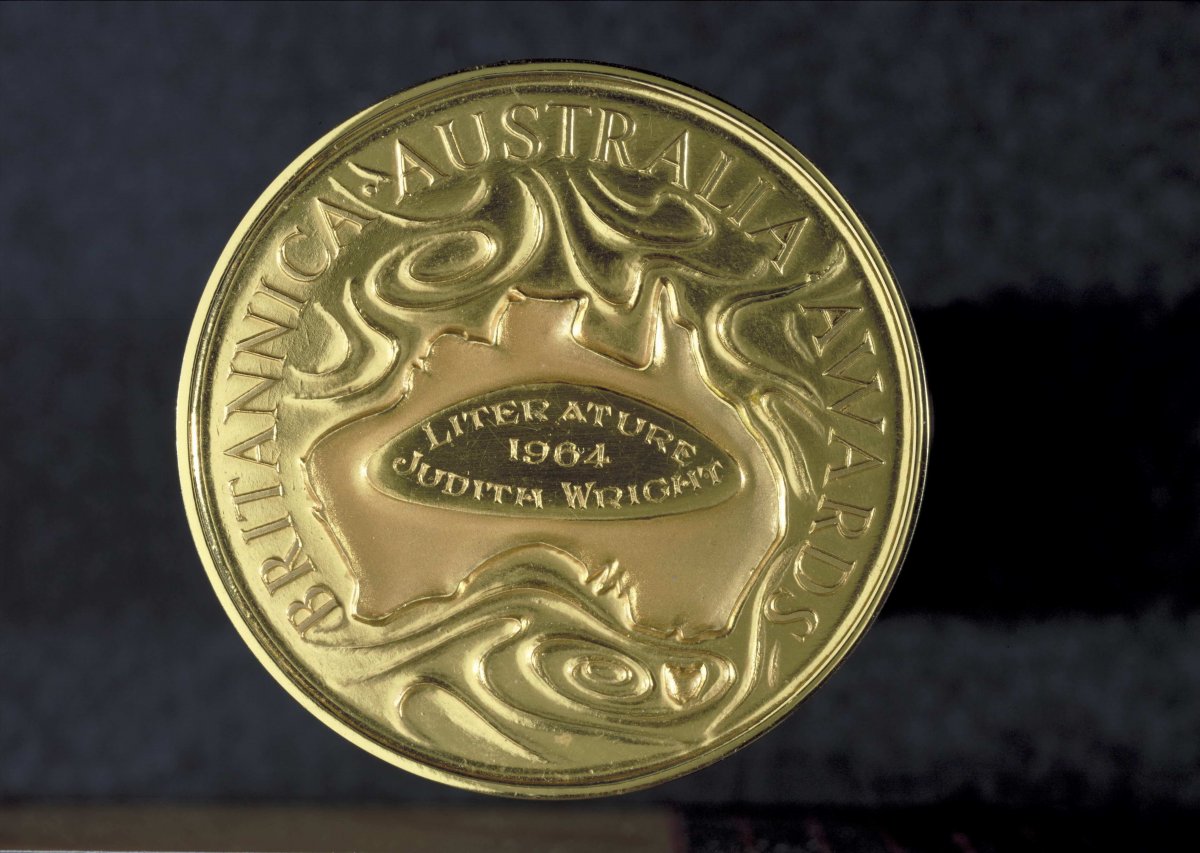

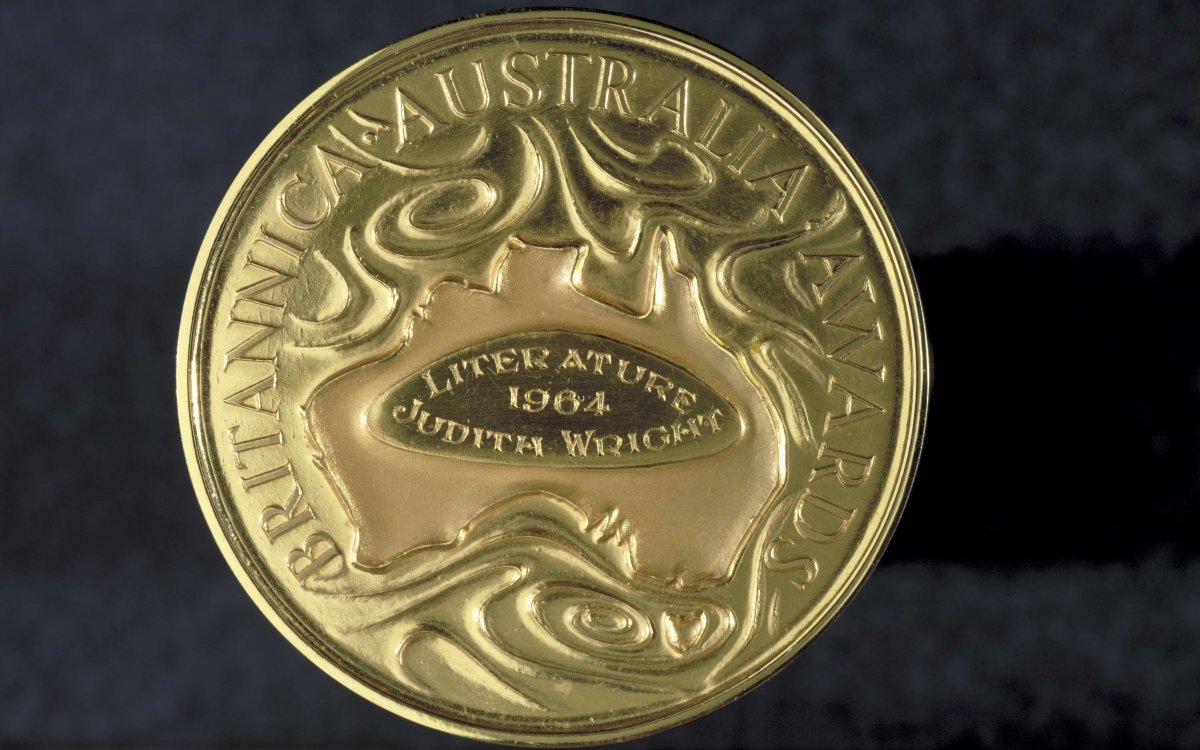

(1964). Britannica Australia Awards Literature medal, 1964, awarded to Judith Wright [realia]. http://nla.gov.au/nla.obj-143523448

Judith Wright (1915–2000) was an activist and one of the world’s most highly regarded poets, becoming the second Australian to be awarded the Queen’s Gold Medal for Poetry in 1992. Wright saw poetry as a way to examine sensitive issues and write social commentary. Her poetry often reflects her increasingly passionate views on environmental issues and Aboriginal rights.

Due to the popularity of her works, Wright became a social figure in Australian culture, which she believed gave her a responsibility to stand up and challenge negative social forces. She founded the Wildlife Preservation Society of Queensland and joined the Aboriginal Treaty Committee to help raise awareness for the need for land rights and a treaty between non-Indigenous and Indigenous Australians: ‘They hadn’t told me the land I loved was taken out of your hands’ (Two Dreamtimes). Consequently, Wright has been called the ‘conscience of the nation’ (judithwrightcentre.com). Some people believe that her passion and commitment to Australia’s environment and the Aboriginal people has helped Australia to shape a sense of itself.

Wright was born into a pastoral family in the New England area of northern New South Wales. Through her poetry, Wright expresses her love of the strange beauty of the Australian landscape and the deep spiritual and mystical connection she felt with the land. Wright saw the land as ancient and full of stories: ‘my blood’s country … full of old stories that still go walking in my sleep’ (South of My Days), unlike the European settlers who viewed the land as new and untouched.

During the 1940s, when researching her grandfather’s diaries for a book, Wright began to understand what had happened to the Aboriginal population during European colonisation—what she refers to as ‘the great pastoral invasion of inland Australia’in Born of the Conquerors (1991). Through this knowledge, she begins to grieve the loss of the culture and traditions of Aboriginal Australians. She writes:

It was not for quite a number of years that something of the reality of my family history began to dawn on me. Though descendants of the tableland’s Aborigines were sometimes employed in cattle work and kitchen, it was never mentioned that only three or four generations earlier, their forebears had been in the sole possession of the land we lived by. I am at least glad that my grandfather Wright had always paid his Aboriginal employees, even though at half rates, for few people did …

My Father once told me, looking out from the escarpment of the tableland across the gulfs which are now part of the New England National Park, of the driving of an Aboriginal group suspected of killing cattle, over the cliff opposite. That story lodged itself in my mind, and a few years later I wrote the poem ‘Nigger’s Leap: New England’. A bora ring and sacred way survived not far from my grandmother’s home, and the paddock was named the Bora Paddock—I wrote ‘Bora Ring’, about that. I am told the ring area has now been ploughed; and a very old carved tree near the woolshed on Wallamumbi where I was brought up has disappeared too. They were some of the last signs of an occupation stretching many thousands of years into the past, but they were not thought worth preserving.

(Judith Wright, Born of the Conquerors, 1991, pp.x–xi)

During her studies at the University of Sydney, Wright often felt that historians neglected Aboriginal history and regarded Indigenous people as invisible: ‘They had rational white faces with eyes that forget the past’ (Two Dreamtimes). Even with her sympathetic views of the Aboriginal plight, Wright acknowledges that it wasn’t until her friendship with Kath Walker, now known as Oodgeroo Noonuccal, that she truly began to understand the realities of Aboriginal life: ‘your eyes were full of the dying children, the blank-eyed taken women’ (Two Dreamtimes).

When Wright started to understand Aboriginal history and because her family had been pioneers, she felt a sense of responsibility and debt. Through her poetry, she wanted to acknowledge the wrongs done to Indigenous people. She also wanted to open the eyes of non-Indigenous people to our true history and to call for some sort of compensation for Indigenous people: ‘I am born of the conquerors/you of the persecuted’ (Two Dreamtimes).

Judith Wright (1915–2000) was an activist and one of the world’s most highly regarded poets, becoming the second Australian to be awarded the Queen’s Gold Medal for Poetry in 1992. Wright saw poetry as a way to examine sensitive issues and write social commentary. Her poetry often reflects her increasingly passionate views on environmental issues and Aboriginal rights.

Due to the popularity of her works, Wright became a social figure in Australian culture, which she believed gave her a responsibility to stand up and challenge negative social forces. She founded the Wildlife Preservation Society of Queensland and joined the Aboriginal Treaty Committee to help raise awareness for the need for land rights and a treaty between non-Indigenous and Indigenous Australians: ‘They hadn’t told me the land I loved was taken out of your hands’ (Two Dreamtimes). Consequently, Wright has been called the ‘conscience of the nation’ (judithwrightcentre.com). Some people believe that her passion and commitment to Australia’s environment and the Aboriginal people has helped Australia to shape a sense of itself.

Wright was born into a pastoral family in the New England area of northern New South Wales. Through her poetry, Wright expresses her love of the strange beauty of the Australian landscape and the deep spiritual and mystical connection she felt with the land. Wright saw the land as ancient and full of stories: ‘my blood’s country … full of old stories that still go walking in my sleep’ (South of My Days), unlike the European settlers who viewed the land as new and untouched.

During the 1940s, when researching her grandfather’s diaries for a book, Wright began to understand what had happened to the Aboriginal population during European colonisation—what she refers to as ‘the great pastoral invasion of inland Australia’in Born of the Conquerors (1991). Through this knowledge, she begins to grieve the loss of the culture and traditions of Aboriginal Australians. She writes:

It was not for quite a number of years that something of the reality of my family history began to dawn on me. Though descendants of the tableland’s Aborigines were sometimes employed in cattle work and kitchen, it was never mentioned that only three or four generations earlier, their forebears had been in the sole possession of the land we lived by. I am at least glad that my grandfather Wright had always paid his Aboriginal employees, even though at half rates, for few people did …

My Father once told me, looking out from the escarpment of the tableland across the gulfs which are now part of the New England National Park, of the driving of an Aboriginal group suspected of killing cattle, over the cliff opposite. That story lodged itself in my mind, and a few years later I wrote the poem ‘Nigger’s Leap: New England’. A bora ring and sacred way survived not far from my grandmother’s home, and the paddock was named the Bora Paddock—I wrote ‘Bora Ring’, about that. I am told the ring area has now been ploughed; and a very old carved tree near the woolshed on Wallamumbi where I was brought up has disappeared too. They were some of the last signs of an occupation stretching many thousands of years into the past, but they were not thought worth preserving.

(Judith Wright, Born of the Conquerors, 1991, pp.x–xi)

During her studies at the University of Sydney, Wright often felt that historians neglected Aboriginal history and regarded Indigenous people as invisible: ‘They had rational white faces with eyes that forget the past’ (Two Dreamtimes). Even with her sympathetic views of the Aboriginal plight, Wright acknowledges that it wasn’t until her friendship with Kath Walker, now known as Oodgeroo Noonuccal, that she truly began to understand the realities of Aboriginal life: ‘your eyes were full of the dying children, the blank-eyed taken women’ (Two Dreamtimes).

When Wright started to understand Aboriginal history and because her family had been pioneers, she felt a sense of responsibility and debt. Through her poetry, she wanted to acknowledge the wrongs done to Indigenous people. She also wanted to open the eyes of non-Indigenous people to our true history and to call for some sort of compensation for Indigenous people: ‘I am born of the conquerors/you of the persecuted’ (Two Dreamtimes).

Judith Wright

These activities introduce students to the poem Bora Ring, as well as to the poem’s background and author. They also develop students’ understanding of how an author’s perspective can change and enhance the meaning of a text.

1. Read the poem with the students without giving any background, the context or the poet’s name and discuss as a class what they believe the poem is about.

- What is the tone of the poem? Encourage students to find quotes from the poem to support their answers.

- Discuss the repetition of words and vowel sounds and how this affects the tone of the poem.

- Discuss what students know of Aboriginal history, culture and religion.

- What happened to the traditional Aboriginal way of life at the beginning of European settlement?

- Have they ever heard of bora rings and what do they think they might be?

2. Ask students whether they have read about bora rings and ask them to speculate about the author.

- Is the author male or female?

- Is the author Indigenous?

- Why would the author choose to write about this subject matter?

3. Have the students read about Judith Wright and bora rings and then read through the poem again. Ask the students whether their understanding of the poem has changed now that they have learnt about Judith Wright and bora rings.

4. Ask the students to choose a period from the nineteenth or twentieth centuries to research. Then have them write a letter to a friend or family member from an Aboriginal person’s perspective and discuss in the letter how that person’s life has been affected by the arrival of Europeans.

Poem - Bora Ring

Analysis of Bora Ring

The poem Bora Ring, like many of Wright’s works, is concerned with the impact of European settlement on Aboriginal culture. Wright uses nature’s perspective to tell the story and mourn the loss of the Aboriginal people, ‘the dancers’, to European settlers, the ‘alien’.

Nature echoes and mimics the dancers in the swaying of branches and the leaves whispering the forgotten ‘chant’. At the same time, nature also mimics the devastation caused by the colonists. The traditional ‘dancing-rings’ have been overgrown until ‘Only the grass stands up’, leaving little behind to show that the Aboriginal people were ever there. The Aboriginal culture has been ‘broken’ and only the trees are left to remember the ‘chant’.

Wright emphasises the destruction of the traditional Aboriginal way of life by using words like ‘gone’, ‘lost’, ‘useless’, ‘broken’, ‘forgot’, ‘splintered’ and ‘still’, highlighting devastation to the original people by those Wright calls ‘conquerors’ and leaving no-one to transmit their ‘song’, ‘dance’ and ‘ritual’ to a new generation. Instead, all we are left with is the colonists’ ‘alien tale’ of events, a one-sided story.

In the third stanza, Wright touches upon the religion and long history of the Indigenous population that was ‘splintered’ by the arrival of European colonists. The ‘dream’ refers to the Dreamtime, the ancient era of creation—‘the world breathed sleeping’. The ‘dream’ was occurring in Australia well before there was written history in other parts of the world (a time that is labelled by historians as prehistory), while the rest of the world was still ‘sleeping’. The colonisation of Australia by Europeans has caused this ancient ‘dream’ to be ‘forgot’ because the Indigenous ‘hunters’, ‘painted bodies’ and ‘nomad feet’ have been ‘splintered’ by settlers.

In the final stanza, Wright alludes to the crimes perpetrated against Indigenous Australians by European settlers by mentioning the biblical story of Cain, an ancient tale of brother killing brother for senseless reasons. The simile invokes the image of Aboriginal people, now living, forgotten by their conquerors in the ‘shadow’ of Western civilisation, which bears the mark of a murderer. It is possible that Cain could be an avenging spirit in the ‘sightless shadow’, seeking retribution for the crimes committed and causing ‘the rider’s heart’ to ‘halt’ in fear. However, it could be that the rider is Wright, and others like her, expressing the shared guilt that we as a nation should feel about the treatment of the Indigenous population and the loss of their traditional ways of life. Consequently, we have turned Indigenous inhabitants into 'sightless shadows’ in their own country, making Australia’s history haunted by ‘shadows’ and ‘unsaid words’ of acknowledgement and apology.

Analysis of Bora Ring

The poem Bora Ring, like many of Wright’s works, is concerned with the impact of European settlement on Aboriginal culture. Wright uses nature’s perspective to tell the story and mourn the loss of the Aboriginal people, ‘the dancers’, to European settlers, the ‘alien’.

Nature echoes and mimics the dancers in the swaying of branches and the leaves whispering the forgotten ‘chant’. At the same time, nature also mimics the devastation caused by the colonists. The traditional ‘dancing-rings’ have been overgrown until ‘Only the grass stands up’, leaving little behind to show that the Aboriginal people were ever there. The Aboriginal culture has been ‘broken’ and only the trees are left to remember the ‘chant’.

Wright emphasises the destruction of the traditional Aboriginal way of life by using words like ‘gone’, ‘lost’, ‘useless’, ‘broken’, ‘forgot’, ‘splintered’ and ‘still’, highlighting devastation to the original people by those Wright calls ‘conquerors’ and leaving no-one to transmit their ‘song’, ‘dance’ and ‘ritual’ to a new generation. Instead, all we are left with is the colonists’ ‘alien tale’ of events, a one-sided story.

In the third stanza, Wright touches upon the religion and long history of the Indigenous population that was ‘splintered’ by the arrival of European colonists. The ‘dream’ refers to the Dreamtime, the ancient era of creation—‘the world breathed sleeping’. The ‘dream’ was occurring in Australia well before there was written history in other parts of the world (a time that is labelled by historians as prehistory), while the rest of the world was still ‘sleeping’. The colonisation of Australia by Europeans has caused this ancient ‘dream’ to be ‘forgot’ because the Indigenous ‘hunters’, ‘painted bodies’ and ‘nomad feet’ have been ‘splintered’ by settlers.

In the final stanza, Wright alludes to the crimes perpetrated against Indigenous Australians by European settlers by mentioning the biblical story of Cain, an ancient tale of brother killing brother for senseless reasons. The simile invokes the image of Aboriginal people, now living, forgotten by their conquerors in the ‘shadow’ of Western civilisation, which bears the mark of a murderer. It is possible that Cain could be an avenging spirit in the ‘sightless shadow’, seeking retribution for the crimes committed and causing ‘the rider’s heart’ to ‘halt’ in fear. However, it could be that the rider is Wright, and others like her, expressing the shared guilt that we as a nation should feel about the treatment of the Indigenous population and the loss of their traditional ways of life. Consequently, we have turned Indigenous inhabitants into 'sightless shadows’ in their own country, making Australia’s history haunted by ‘shadows’ and ‘unsaid words’ of acknowledgement and apology.

Activities—Poem analysis

These activities draw on the students’ knowledge of Judith Wright and of bora rings. They develop students’ understanding of a variety of language features, images and vocabulary, and how these influence the audience and affect meaning.

1. Stanza One

- Who are the ‘dancers’ and why are they in the ‘earth’?

- Explain why the ‘song is gone’, ‘the dance secret’ and ‘the ritual useless’?

- Who is the ‘alien’ and why do you think the poet describes them in this way?

- What happened historically to make the ‘tribal story lost in an alien tale’?

2. Stanza Two

Answer the following:

- What is the grass marking?

- Who are the trees mimicking and what words does Wright use to demonstrate this?

- What does Wright’s use of nature symbolise in this verse?

Draw an image to represent what is being described in this verse.

3. Stanza Three

- Who is Wright referring to when she writes ‘painted bodies’ and ‘nomad feet’ and how does this portray them in the poem?

- What do you think ‘the spear splintered underground’ symbolises?

- The line ‘a dream the world breathed sleeping and forgot’ is referring to religion and history. What is the ‘dream’, why is the world ‘sleeping’, and who ‘forgot’?

4. Stanza Four

- Who do you think the ‘rider’ represents?

- ‘Cain’ refers to a biblical story in which Cain kills his brother Abel. Why do you think Wright refers to Cain in this poem and who do you think Cain represents?

- What do you think Wright means by ‘an unsaid word’?

5. Read the poem We Are Going by Kath Walker (later known as Oodgeroo Noonuccal), an Indigenous activist and Wright’s good friend. Then compare Wright’s and Noonuccal’s perspectives.

Activity—Poetry analysis essay

This activity introduces students to writing essays that analyse poetry, using the information they have already gathered through their earlier analysis of the poem. Encourage students to do further research on Judith Wright and Australian history to help support their essay.

How does the poem Bora Ring demonstrate Wright’s perspective on Indigenous Australians?

- Use quotes from the poem to support your answer.

- To help you formulate your argument, think about what this poem tells us about the poet Judith Wright and how she views Aboriginal people.

- Write an introductory paragraph (around 4 or 5 sentences) that briefly introduces Wright, her views on Indigenous issues and how the poem Bora Rings reflects her perspective on these issues.

- Write a paragraph on each of the verses, analysing what each verse is about. Use quotes from the poem to support your answer. Make sure that you relate the analysis to the overall question being asked.

- Write a concluding paragraph that restates the main ideas of your argument.

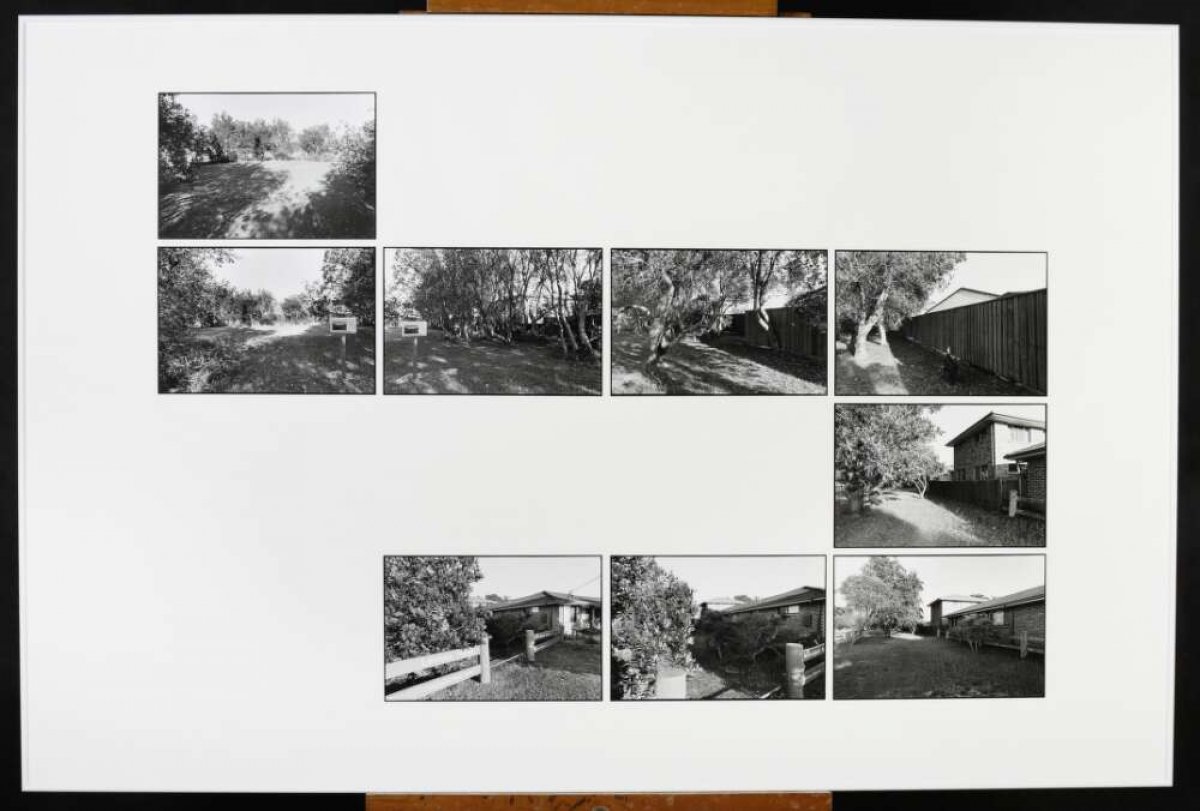

Bora Rings

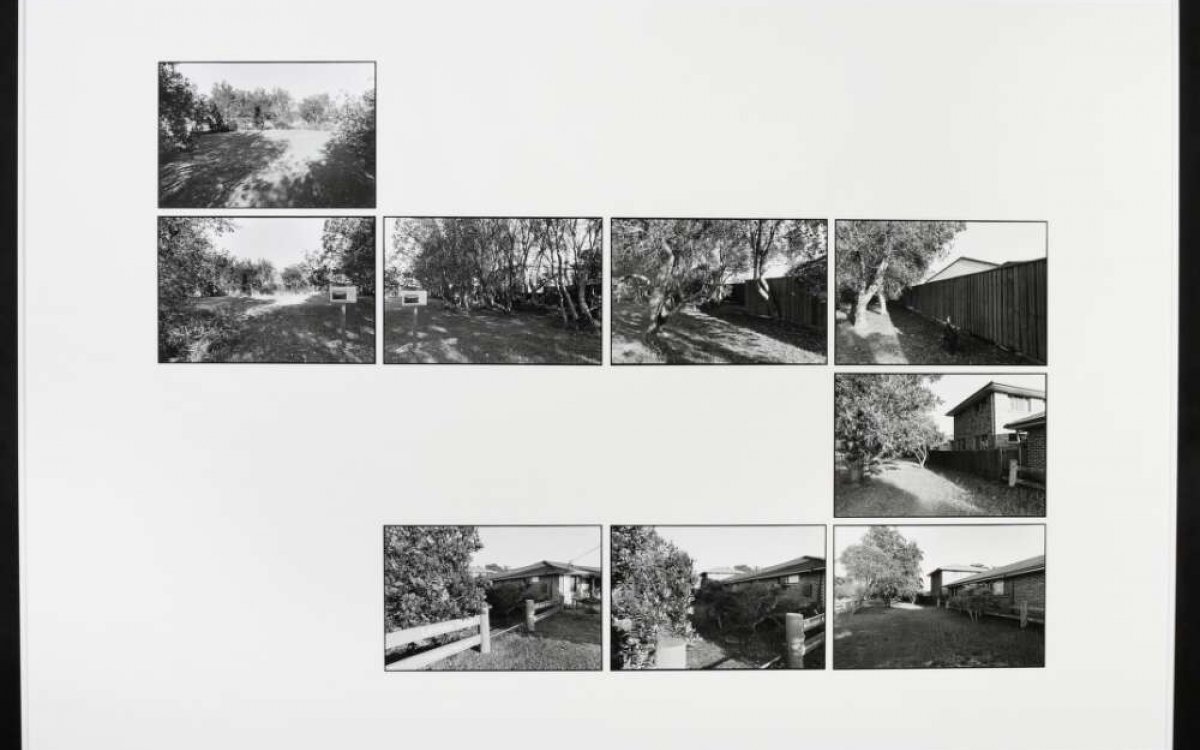

Rhodes, Jon, 1947-. (2004). Suburban Bora, Bundjalung, Lennox Head, New South Wales, 2004 [picture] / Jon Rhodes. http://nla.gov.au/nla.obj-147626662

Bora rings are unique cultural sites. They are evidence of the ceremonial and religious life of Aboriginal people. Found mainly in south-eastern Australia, they are circular structures of stone or foot-hardened earth surrounded by raised embankments. They were generally constructed in pairs (although some sites have three), with a bigger circle of about 22 metres in diameter and a smaller one of about 14 metres. The rings are joined by a sacred walkway and, in the past, would have been surrounded by campsites for visiting groups attending the ceremony. Young boys went through an initiation ceremony (called a bora) on the rings, in which they were introduced to the traditional knowledge of the men. When the bora ceremonies involved many groups, they also were an opportunity for trade and other social activities. Major ceremonies often attracted hundreds or possibly thousands of people.

Concluding activities

1. Have students research an Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander sacred site. The sacred site could be a tree, a waterhole or another natural feature, or it could be rock art, a totem and so on. Students should describe its location, how it was used in the past, its significance to the local Indigenous population and the impact of European settlement on the site.

NOTE Warn students of Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander heritage that they may see names and images of, or reference to, deceased persons in their research.

2. After completing their research, ask students to write a blog post, wiki page or newspaper article about the sacred site.

3. Have students write a poem from their own perspective that reflects on how the sacred site was once used and how it has been affected by the passing of time.