This theme supports the following Content Descriptions and Elaborations for Year 8 History

AC9HH8K01

- The transformation of the ancient world to the early modern world, from the decline of the Roman Empire in western Europe through Medieval, Renaissance, or pre-modern Europe

The Roman Empire

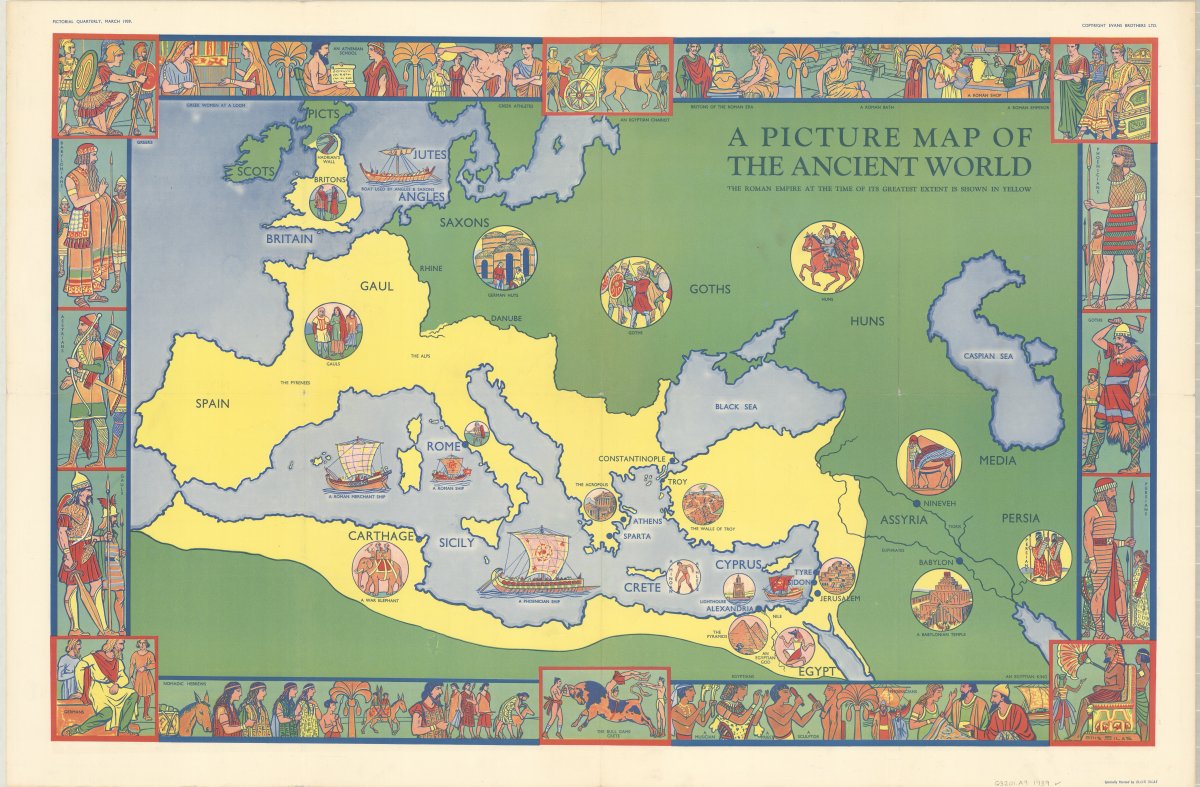

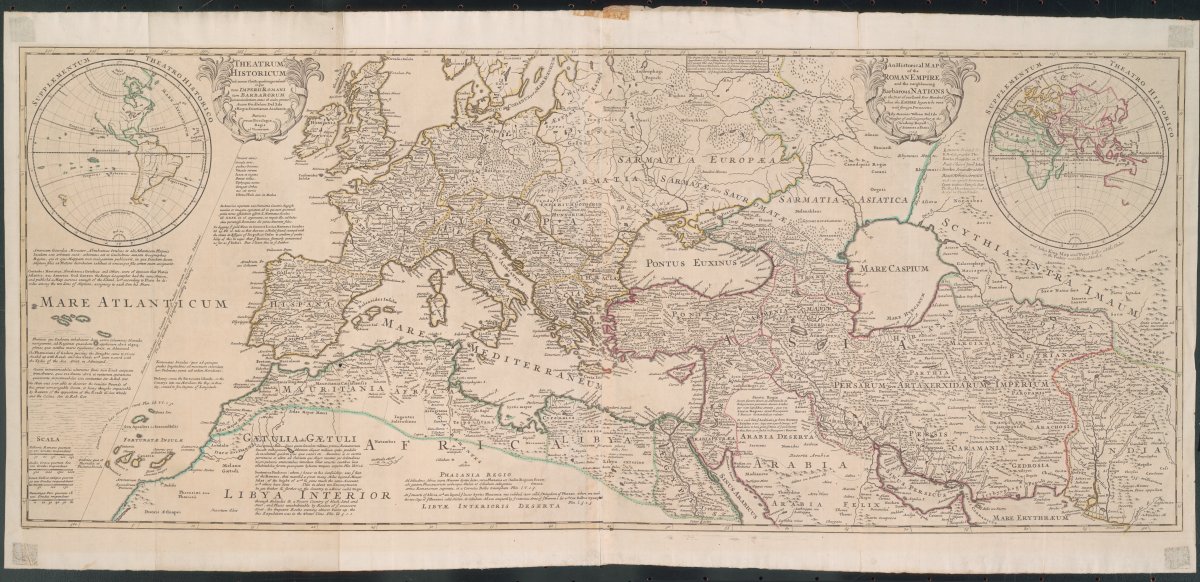

Silas, Ellis Luciano, 1885-1972 & Evans Brothers Ltd. (1939). A picture map of the ancient world / specially painted by Ellis Silas. https://nla.gov.au/nla.obj-2378561352

Throughout human history, societies have grown, matured, and then collapsed, making way for new innovations, people and philosophies to begin the cycle again, building on what came before. The history of Medieval Europe is no different: it has its roots in the collapse of the western Roman Empire in 456 CE.

Rome’s history is said to have begun in 753 BCE with the founding of the city by legendary twins Romulus and Remus, who the legend says were raised by a wolf after being abandoned as babies.

The story of Romulus and Remus is just one of many that tell of Rome’s founding, but it remains the most enduring; however, the truth surrounding the actual events of Rome’s foundation is unknown.

Regardless of its beginnings, Roman influence expanded well beyond its central Italian powerbase quickly.

At its height, in 117 CE, the Roman Empire (Latin: Imperium Romanum) encompassed approximately 5 million square kilometres, stretching from Hadrian’s Wall in the north of England to the shores of the Red Sea along the coast of Egypt. For comparison, the modern European Union encompasses approximately 4.4 million square kilometres. The period between 27 BCE and 180 CE is known as the Pax Romana (Roman Peace); it was a time of stability and peace throughout the empire.

(1856). The Roman Forum, looking towards the ruins of the temple of Saturn, Rome, Italy [picture]. http://nla.gov.au/nla.obj-151254857

East and West

When an empire extends too far, cracks start to appear. With such a large territory for Rome to control, problems began to arise.

The decline of Roman control was not the result of one event, but a culmination of many events over a period of time. Historians throughout the years have considered many reasons that lead to the fall of the Roman Empire. As with many civilisations, decline and collapse is not the result of one factor.

To restore stability, the Emperor Diocletian split the Empire in two in 286 CE, with each territory to be ruled by a senior and junior emperor, two in the east and two in the west. It was hoped that with smaller territories to administer, the four emperors could more easily address the issues facing the Empire.

Some of the reasons scholars credit with eroding the stability of Rome:

- Resistance from societies on the borders of the Empire, while always present, began to increase in both scale and frequency;

- Vast numbers of refugees, fleeing unrest and invasion, descended on Roman cities, adding pressures on health and public infrastructure;

- Diseases ran through parts of the Empire, brought by soldiers returning from campaigns and spread in the densely populated urban areas;

- Divisions within the ruling classes saw the once-efficient administration of the Empire and its provinces crumble and the citizens who made up the Empire became angry at the government;

- A succession of ineffective, negligent and deeply unpopular emperors undermined the faith in and power of the crown. In some cases, direct action (including building lavish palaces for themselves) by an emperor cost the Empire large swaths of territory, money and people, or all three.

Some of the reasons scholars credit with eroding the stability of Rome:

- Resistance from societies on the borders of the Empire, while always present, began to increase in both scale and frequency;

- Vast numbers of refugees, fleeing unrest and invasion, descended on Roman cities, adding pressures on health and public infrastructure;

- Diseases ran through parts of the Empire, brought by soldiers returning from campaigns and spread in the densely populated urban areas;

- Divisions within the ruling classes saw the once-efficient administration of the Empire and its provinces crumble and the citizens who made up the Empire became angry at the government;

- A succession of ineffective, negligent and deeply unpopular emperors undermined the faith in and power of the crown. In some cases, direct action (including building lavish palaces for themselves) by an emperor cost the Empire large swaths of territory, money and people, or all three.

Religious tension

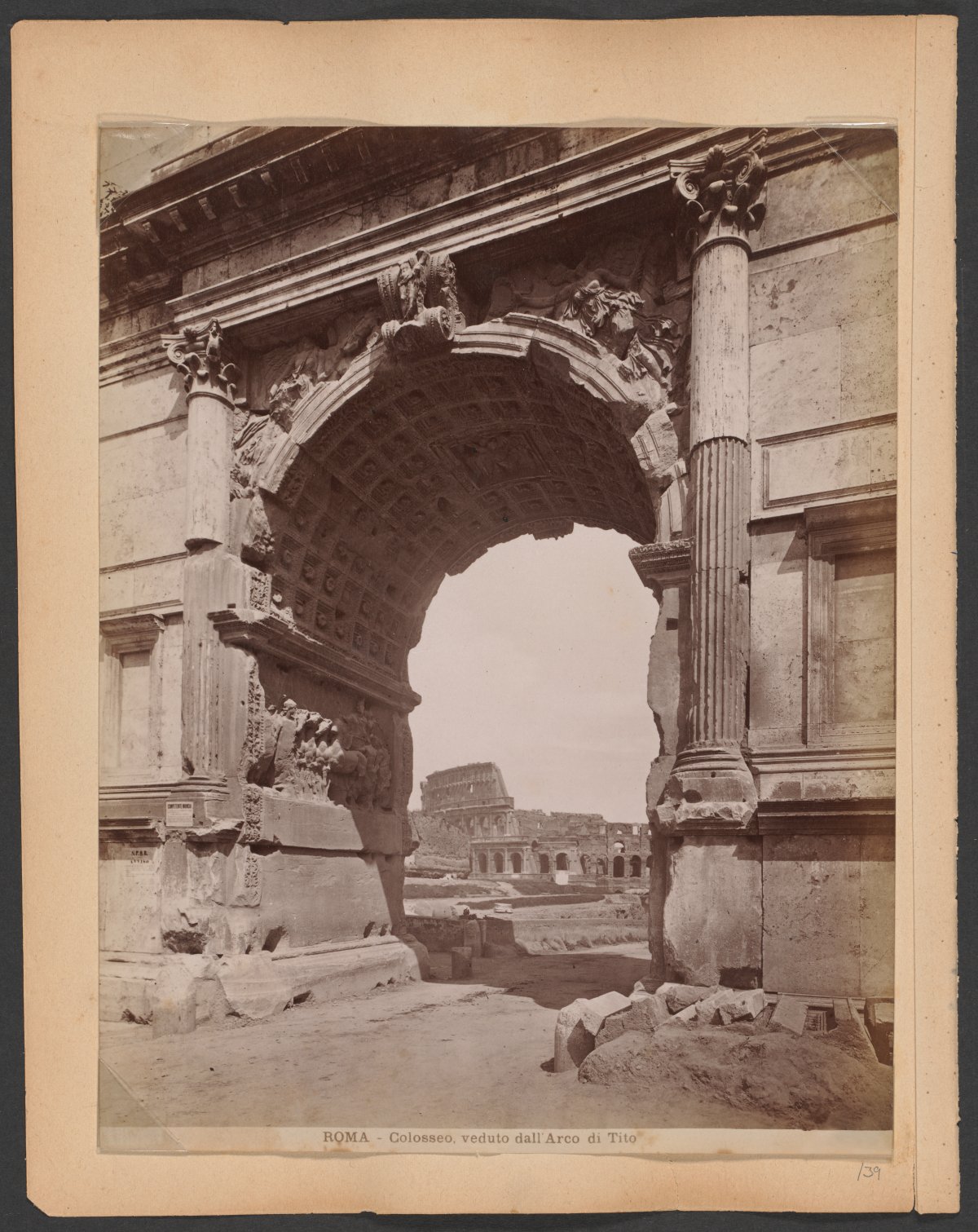

One major disruption to the stability of Roman rule was the increased religious tensions within the diverse populations of the Empire. Of particular importance during this time was the growing spread of Christianity. Although the movement was small at first, conflict and unrest were common between believers and opposition. Rome had long been tolerant of many beliefs and religions, but the ruling elite increasingly saw the influence of Christianity as a threat to their power, and several emperors outlawed the practice of Christianity and imposed harsh penalties on its followers. These laws included fines, whippings and, perhaps the most well-known, the damnatio ad bestias (condemnation to the beasts) in which offenders were sentenced to be killed by wild animals in a public spectacle in the Colosseum of Rome or other arenas. Despite their brutality, these laws did little to stop the spread of the religious movement.

(1900). Colosseum, Rome, Italy, approximately 1900. http://nla.gov.au/nla.obj-2934613650

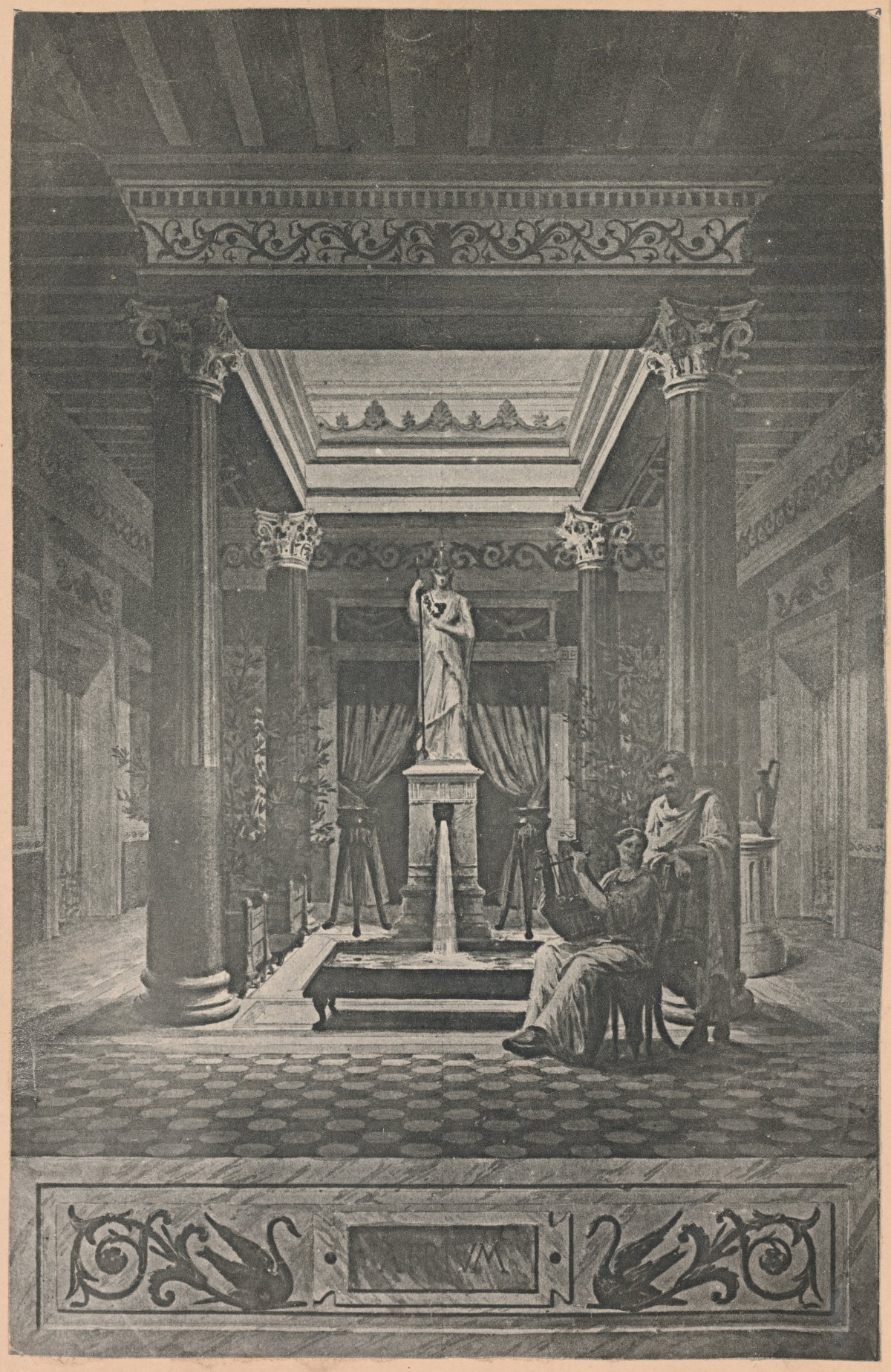

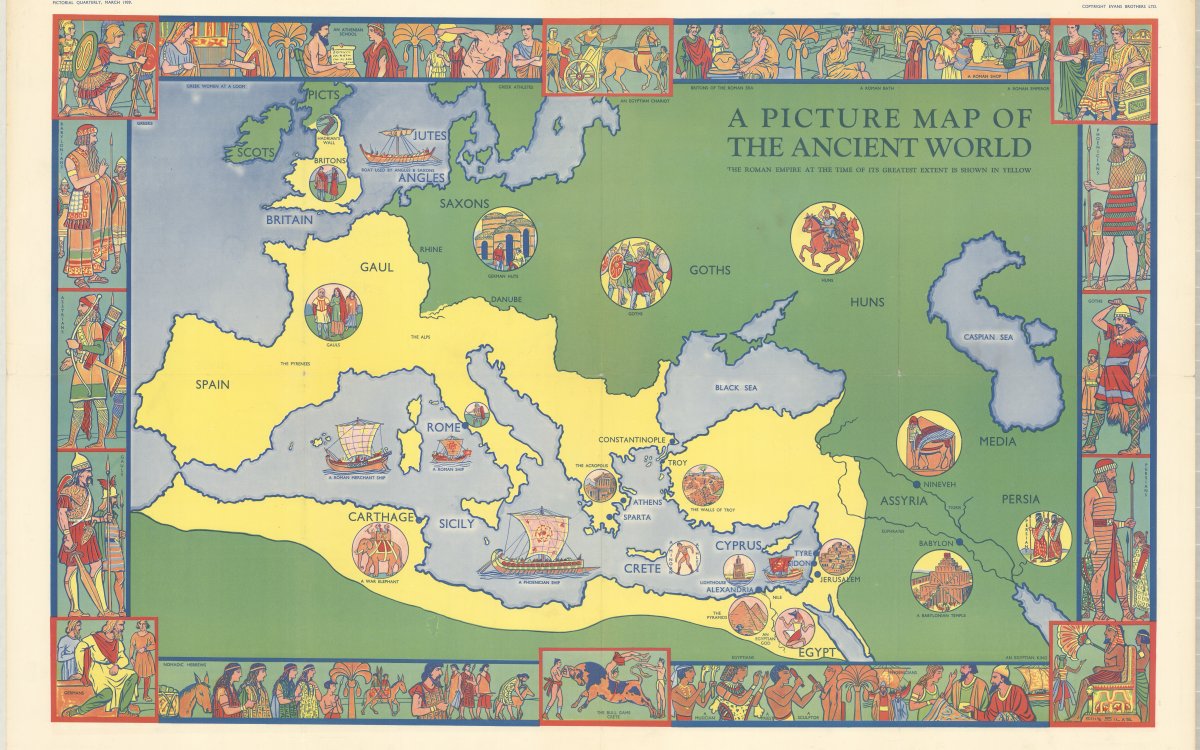

Henry, Lucien, 1850-1896. (1888). [Illustration; Ancient Rome scene] [picture] / Lucien Henry. https://nla.gov.au/nla.obj-140573327

The ancient Romans worshipped a pantheon or range of gods, spirits and entities. A religion with many gods is called polytheistic (Greek: poly = many and theos = god). While the gods were believed to control the fates, people also venerated the emperors as living gods on Earth.

In Christianity, followers worship only one god instead of many and believe Jesus of Nazareth is the only son of God. A religion that worships only one god is called monotheistic (Greek: mono = one). Christian teachings state that God and his son are the highest authority and even the emperors and kings of the Earth rank below them. This teaching was part of the reason for hostility towards Christians in Roman times, as it was seen to weaken the power and image of the Roman emperor.

The ancient Romans worshipped a pantheon or range of gods, spirits and entities. A religion with many gods is called polytheistic (Greek: poly = many and theos = god). While the gods were believed to control the fates, people also venerated the emperors as living gods on Earth.

In Christianity, followers worship only one god instead of many and believe Jesus of Nazareth is the only son of God. A religion that worships only one god is called monotheistic (Greek: mono = one). Christian teachings state that God and his son are the highest authority and even the emperors and kings of the Earth rank below them. This teaching was part of the reason for hostility towards Christians in Roman times, as it was seen to weaken the power and image of the Roman emperor.

A sign from God

Hostilities towards Christians continued under successive emperors. However, the outlook for the Christians changed in the rule of Emperor Constantine. During the period known as the Civil Wars of the Tetrarchy (306–324 CE), Constantine was engaged in a struggle against the other rulers of the Empire, each refusing to acknowledge the others as legitimate emperors under the four-emperor system. Prior to a battle against rival Emperor Maxentius in 312 CE, Constantine is said to have had a dream in which the Christian God told him to mark his army with the sign of Jesus Christ’s initials. Constantine ordered the shields and standards of his army be marked with the symbols and marched to battle. He was victorious, despite being outnumbered, and believed the victory was a favour of the Christian God.

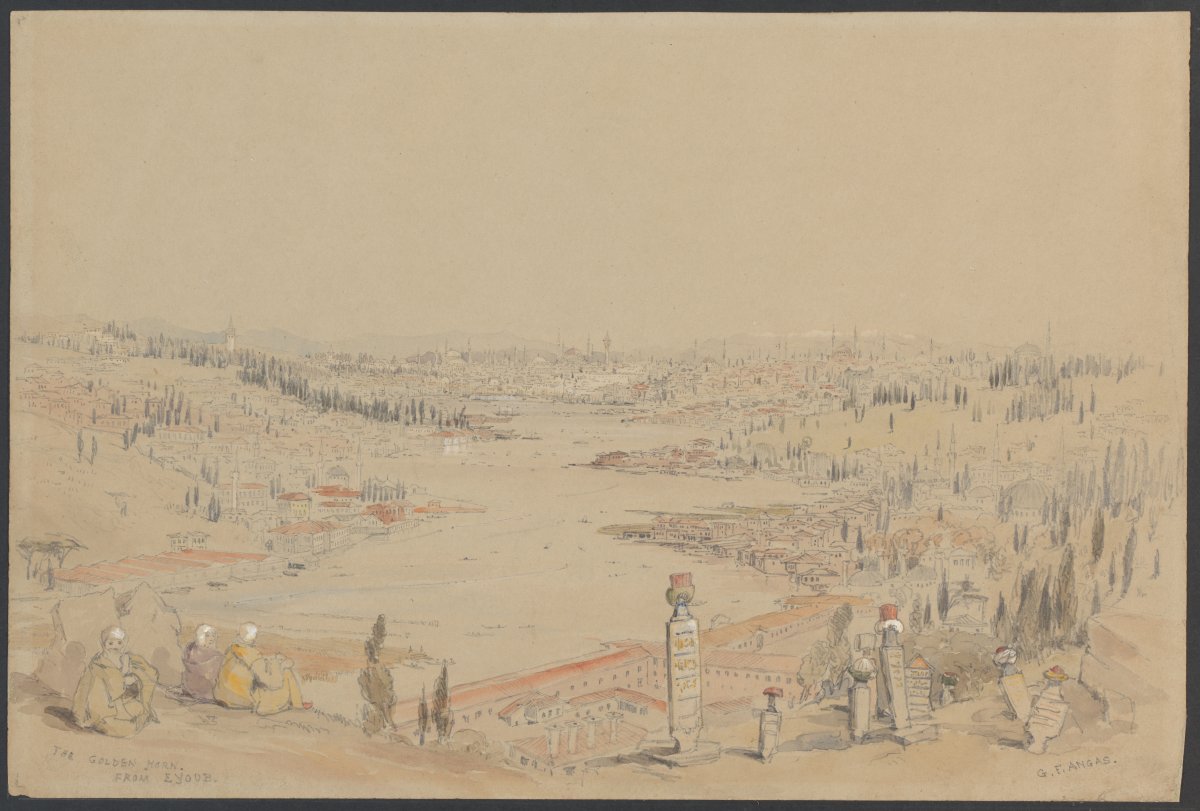

Following the battle, Emperor Constantine converted to Christianity, but he maintained a tolerance of the old traditions of Rome. Along with co-emperor Licinius, Constantine signed the Edict of Milan, which granted rights and tolerance to Christians and all other religions in the Empire if the people remained loyal to the emperor. Licinius later went on to resume persecuting Christians. Eventually Constantine and Licinius would go to war. Constantine was victorious and became the sole ruler of Rome. He would move the main capital of the Empire to the city of Byzantium, which was renamed Constantinople (Latin: Constantinopolis = The City of Constantine) around 330 CE. The city would retain this name until the early twentieth century.

Angas, George French, 1822-1886. (1848). The Golden Horn from Eyoub [i.e. Eyub], Constantinople, 1848 [picture] / G.F. Angas. http://nla.gov.au/nla.obj-133001219

Under Constantine, those who followed the Christian faith were secure to practise their religion. Constantine continued to use the initials of Jesus on his coins and passed a law saying that Sunday was to be a day of rest. Despite Constantine’s acceptance of other religions, his successors, who maintained the Christian faith, began to dismantle the systems and rituals of other religions. Some would go as far as removing statues of the Roman gods from public spaces. At the end of the third century CE, Emperor Theodosius I passed many laws that restricted and diminished the standing of religions other than Christianity. He decreed that pagan holidays were to be standard workdays; however, the festivities did continue. With backing by the government and Emperor, Christian supporters took it upon themselves to remove as many traces of Rome’s old religion and symbols as they could. They tore down statues and temples, chipped away mosaics, and graffitied temples and walls with the image of the cross.

Fall of the Roman Empire

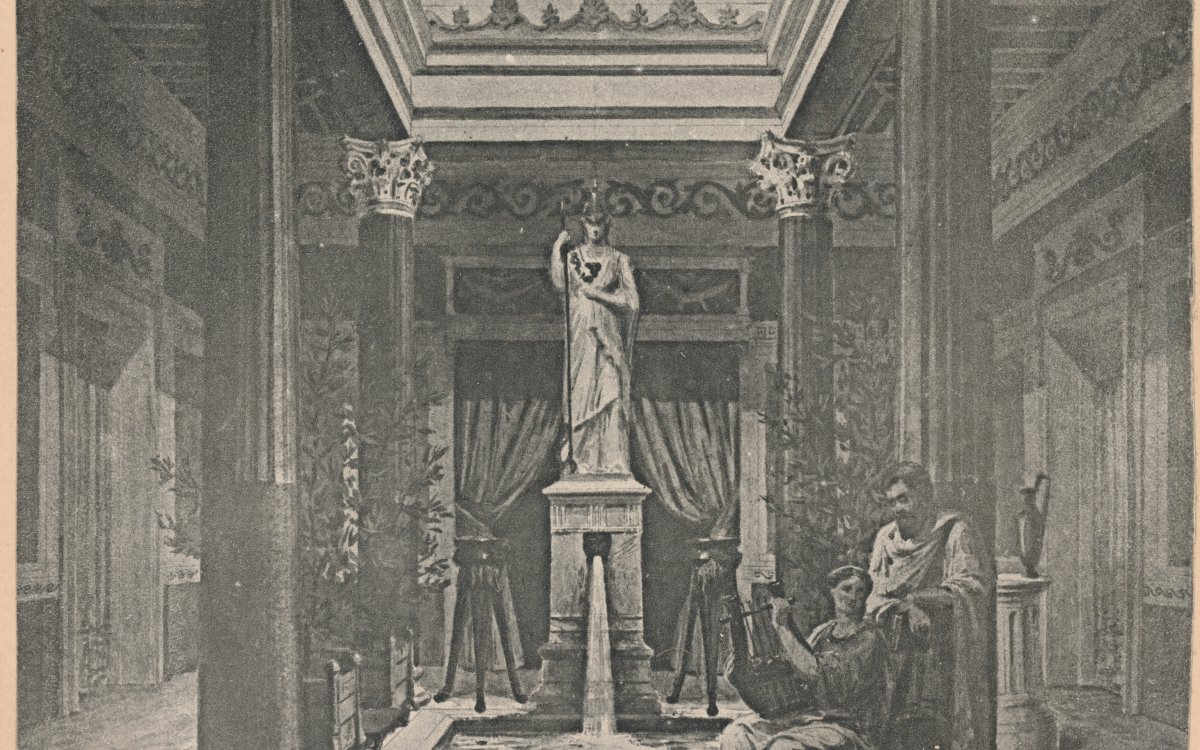

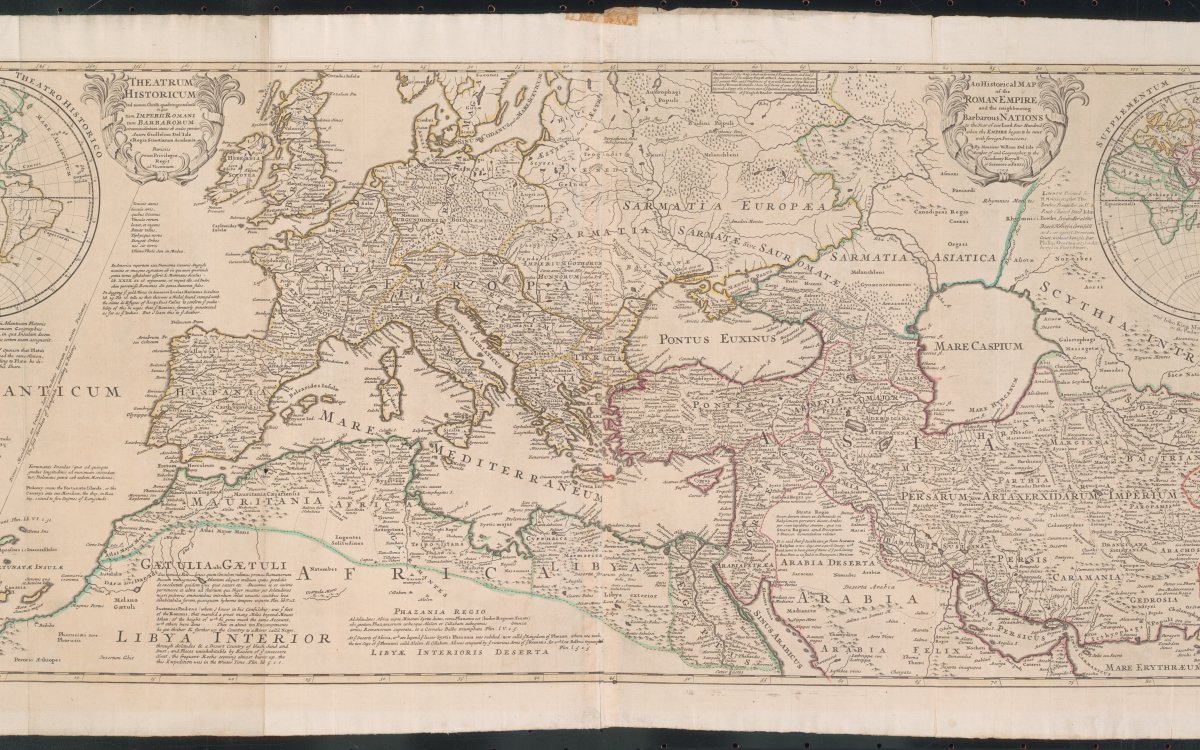

By the late third century CE, the Western Empire had become a shadow of its former self. Relationships with surrounding kingdoms and tribes were worsening, and the borders of the western territories were constantly under siege, especially from the peoples known as the Goths and Vandals. Conflict between religious groups was still causing problems for the government, and trade and taxation were disrupted due to these conflicts.

This map shows the state of the Roman Empire in the year 400 CE. The western Empire can be seen in yellow outline and the eastern Empire can be seen in red. The map also highlights “Barbarian nations” with blue. This map was printed in 1709 from historical sources. It includes insets of the “modern world” to put the Roman Empire in context.

L'Isle, Guillaume de, 1675-1726 & H. Moll (Bookseller) & John Bowles, firm, London & John King (Bookseller) & Phillip Overton (Bookseller) & Thomas Bowles (Bookseller). (1709). An historical map of the Roman Empire and the neighbouring Barbarous nations [cartographic material] : to the year of our Lord four hundred when the Empire began to be rent with foreign invasions / by Monsieur William Del Isle, member of and Geographer to the Academy Royall of Sciences at Paris. = Theatrum Historicum... tum Imperii Romani tum Barbarorum... Autore Guillelmo Del'Isle. http://nla.gov.au/nla.obj-230683586

In 410, a group of Visigoths led an assault on the city of Rome. While the capital of the western Empire had moved to Ravenna two years earlier, Rome was still an important cultural and religious centre. The Visigoths sacked the city. This was the first time in 800 years that the city of Rome had been sacked. In the following decades, Rome would be looted and burned several more times by Goths and Vandals.

In 476 CE, a Germanic chieftain, Odoacer (sometimes written Odovacar), led an attack on Rome and entered the city after a seige, dethroning the Emperor Romulus Augustus and declaring himself King of Italy.

Historians mark 476 as the year in which the western Roman Empire collapsed. This is also generally considered to be the end of the Ancient Era and the beginning of the Medieval Era. Despite the collapse of the western Roman Empire, the eastern Empire continued to thrive for almost another 1000 years, finally falling in 1453 CE.

Activities

- The Roman Empire covered more than 5 million square kilometres at its height.

- Using a modern political map and a map showing the extent of the Roman Empire, trace the territory of the Roman Empire and the countries of modern Europe that it covered. A list of maps can be found here.

- Label major Roman cities and settlements and compare their location to modern centres

- The Romans used many innovations and technologies to make life easier and more efficient. They are well known for their sanitation systems, health care system, roads and aqueducts.

- Have students investigate what kinds of technology the Romans invented and how they used it.

- Have students consider the importance of these innovations with regard to running a large empire.

- Have students consider: how do we know what technologies the ancient Romans had? How do we know how they used them?

- Do we still use any Roman inventions today, in modern form?

- When an influential power collapses, a power vacuum is created, with others stepping in to take control.

- Have the students write a creative piece in which they hypothesise what would happen if one day all adults went missing.

- Have them document how life would change in a day, a week, a month, a year, etc.

- Have them consider how their lives would change. How would school change? How would their town change? How would the country change?

- What dangers might there be?

- Have the students write a creative piece in which they hypothesise what would happen if one day all adults went missing.

This module supports the follow Achievement Standards for the Australian Curriculum: Year 8 Learning area

Students describe the historical significance of the periods between the ancient and modern past.

They explain the causes and effects of events, developments, turning points or challenges in Medieval, Renaissance, or pre-modern Europe, or in the societies connected to empires or expansions, or the societies of the Asia-Pacific world during these periods.

They describe the social, religious, cultural, economic, environmental and/or political aspects related to the changes and continuities in a society or a historical period.

Students describe the role of significant individuals, groups and institutions connected to the societies of these periods and their influences on historical events.

Students develop questions about the past to inform historical inquiry.

They sequence events and developments to explain causes and effects, and patterns of continuity and change across societies and time periods.