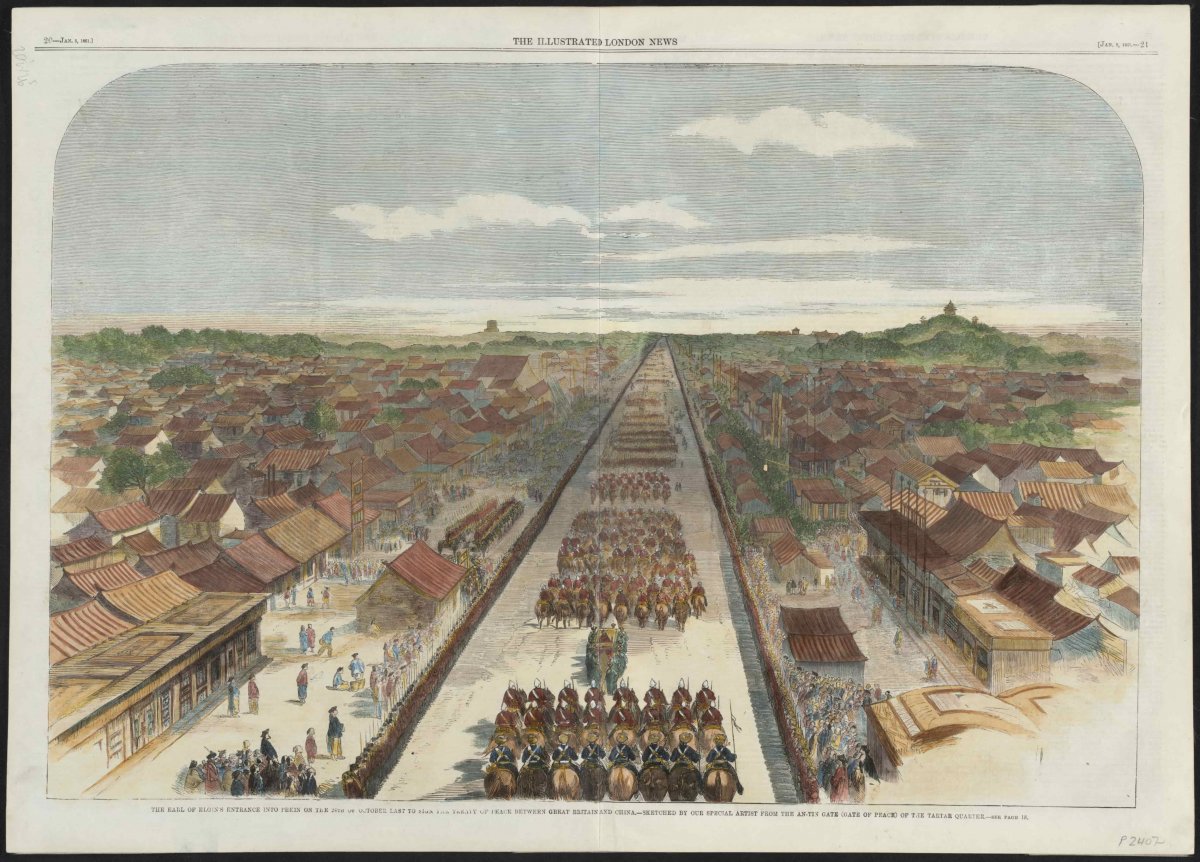

(1861). The Earl of Elgin's entrance into Pekin on the 24th of October last to sign the Treaty of Peace between Great Britain and China / sketched by our special artist from the An-Tin Gate (Gate of Peace) of the Tartar Quarter. http://nla.gov.au/nla.obj-128383685

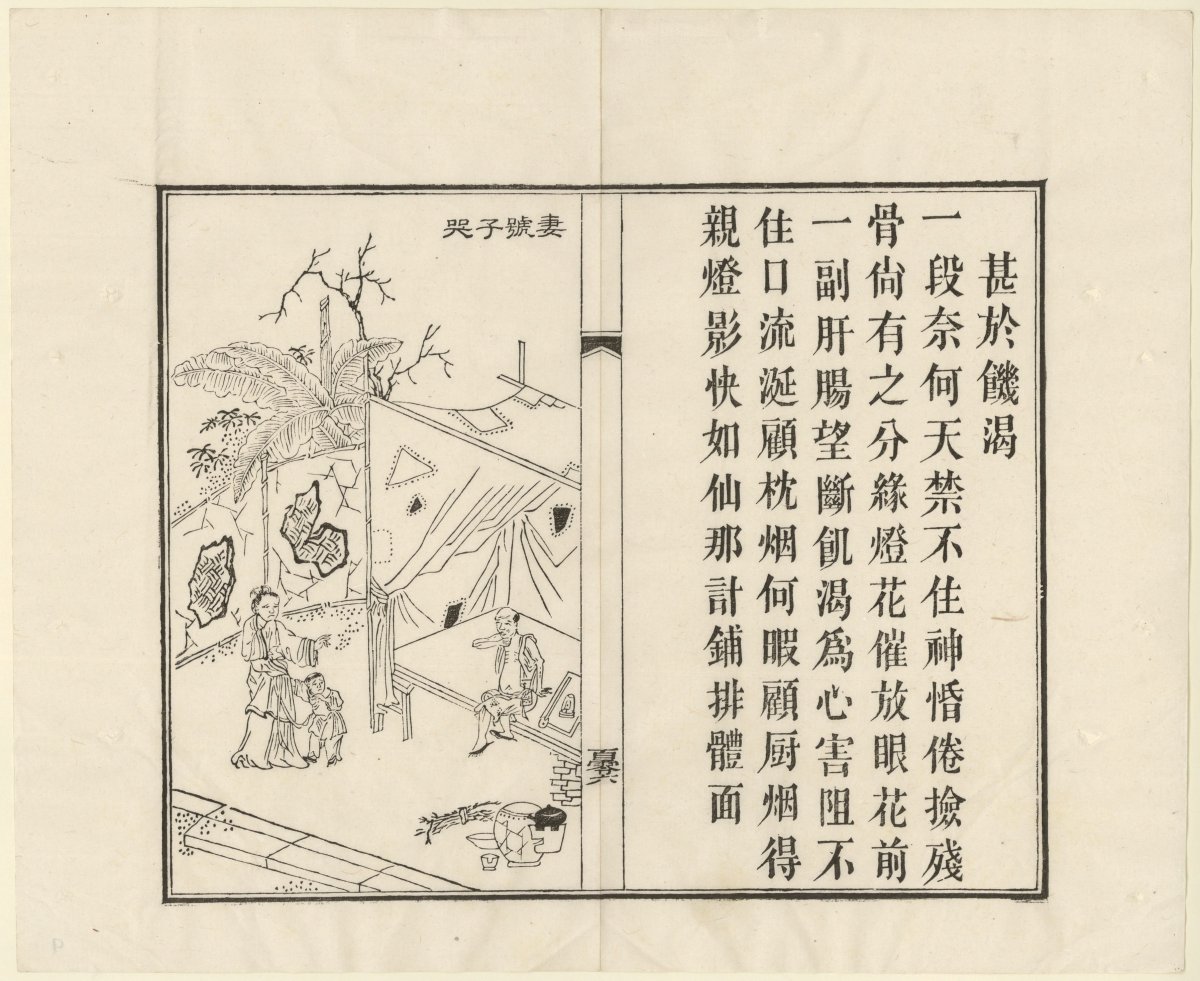

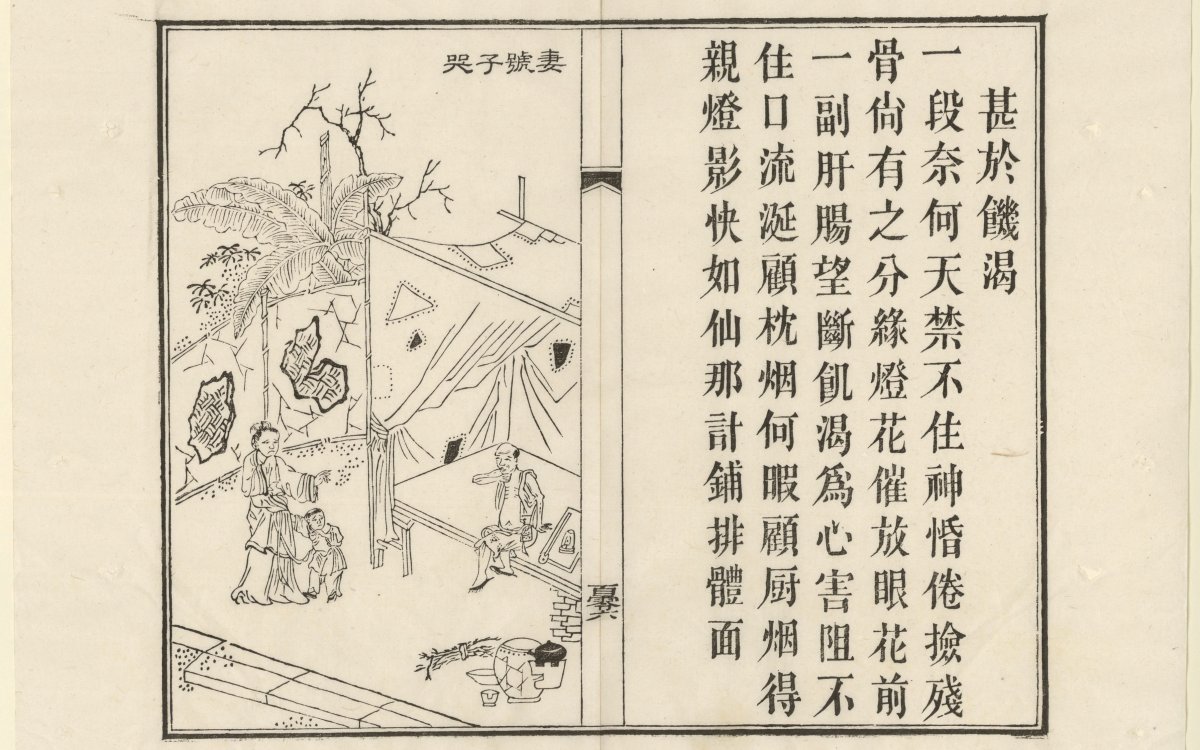

(1800). Quan jie shi ya pian yan. [S.l. : s.n. http://nla.gov.au/nla.obj-46102644

In the nineteenth century some major challenges to Manchu rule appeared from abroad. European powers were expanding their trade in the East, and by the early 1800s Great Britain and other Western countries had struck on a product they could market in China—opium—and were shipping it in huge volumes. By the 1830s a tenth of all British revenues in India came from the sale of opium. But this came at social and financial cost to Qing society. In 1839 the Qing court sent the official Lin Zexu (1785–1850) to Canton with a mandate to halt the trade. Western merchants rejected his appeals, which prompted the Qing to seize their opium, a tactic that let ultimately to the first of the Opium Wars. The British were victorious and the Treaty of Nanjing (1842) forced the opening up of five of China’s ports to trade, the payment of an indemnity and the ceding of Hong Kong to Britain. The British Foreign Secretary, Lord Palmerston, was unimpressed with the procurement of Hong Kong, labelling the place ‘a barren island with hardly a house upon it’.

The Second Opium War, also known as the Arrow War, was fought between 1856 and 1860 over similar issues. Its first phase was concluded by the Treaty of Tianjin (1858), which opened up more Chinese ports to foreign trade, permitted the presence of foreign legations in Beijing and the work of Christian missionaries in the country, and legalised the importation of opium. After the Qing court revoked these unequal terms and some of the negotiators dispatched to Beijing were killed, British and French forces marched on the capital. They arrived outside Beijing in early October and established themselves opposite Anding Gate on the northern side of the city walls. On 9 October artillery pieces were brought up, emplaced to the east of the gate, in the Temple of Earth, and trained on the wall. The British and French delivered an ultimatum: surrender the Anding Gate by the 13th or the city would be taken by storm. The field guns were part bluff, for it was unlikely they could have rapidly forced a breach in the city’s wall, some 18 metres thick at this point. In the event, the gate was surrendered on the morning of the final day. But further demands for the ratification of the treaty were not met, and so on 17 October Lord Elgin (1811–1863), commander of British forces, ordered the looting and burning of the imperial gardens to the north-west of Beijing, and threatened the same for the Imperial Palace. He was eager to conclude proceedings before the onset of winter and reasoned this act would punish what he saw as the intransigent court rather than the city’s innocent inhabitants. The court finally capitulated and reparations were paid. On 24 October, the day the British signed a convention with the Qing court, Lord Elgin marched his forces through the city. The French did the same the next day.

In the nineteenth century some major challenges to Manchu rule appeared from abroad. European powers were expanding their trade in the East, and by the early 1800s Great Britain and other Western countries had struck on a product they could market in China—opium—and were shipping it in huge volumes. By the 1830s a tenth of all British revenues in India came from the sale of opium. But this came at social and financial cost to Qing society. In 1839 the Qing court sent the official Lin Zexu (1785–1850) to Canton with a mandate to halt the trade. Western merchants rejected his appeals, which prompted the Qing to seize their opium, a tactic that let ultimately to the first of the Opium Wars. The British were victorious and the Treaty of Nanjing (1842) forced the opening up of five of China’s ports to trade, the payment of an indemnity and the ceding of Hong Kong to Britain. The British Foreign Secretary, Lord Palmerston, was unimpressed with the procurement of Hong Kong, labelling the place ‘a barren island with hardly a house upon it’.

The Second Opium War, also known as the Arrow War, was fought between 1856 and 1860 over similar issues. Its first phase was concluded by the Treaty of Tianjin (1858), which opened up more Chinese ports to foreign trade, permitted the presence of foreign legations in Beijing and the work of Christian missionaries in the country, and legalised the importation of opium. After the Qing court revoked these unequal terms and some of the negotiators dispatched to Beijing were killed, British and French forces marched on the capital. They arrived outside Beijing in early October and established themselves opposite Anding Gate on the northern side of the city walls. On 9 October artillery pieces were brought up, emplaced to the east of the gate, in the Temple of Earth, and trained on the wall. The British and French delivered an ultimatum: surrender the Anding Gate by the 13th or the city would be taken by storm. The field guns were part bluff, for it was unlikely they could have rapidly forced a breach in the city’s wall, some 18 metres thick at this point. In the event, the gate was surrendered on the morning of the final day. But further demands for the ratification of the treaty were not met, and so on 17 October Lord Elgin (1811–1863), commander of British forces, ordered the looting and burning of the imperial gardens to the north-west of Beijing, and threatened the same for the Imperial Palace. He was eager to conclude proceedings before the onset of winter and reasoned this act would punish what he saw as the intransigent court rather than the city’s innocent inhabitants. The court finally capitulated and reparations were paid. On 24 October, the day the British signed a convention with the Qing court, Lord Elgin marched his forces through the city. The French did the same the next day.

In relation to the West, when the Qing dynasty began in 1644, access to Chinese markets for the Portuguese, Spanish, Dutch and English had been restricted to Canton since 1550. Europeans were not allowed to reside in Canton. However China remained a place of infinitive fascination and possible opportunity for Western leaders and merchants.

The West tried through diplomatic, religious and other more aggressive methods to gain access and influence in China, and there were consequences for the Chinese people and the Qing dynasty.

Discuss the Opium Wars with the group.

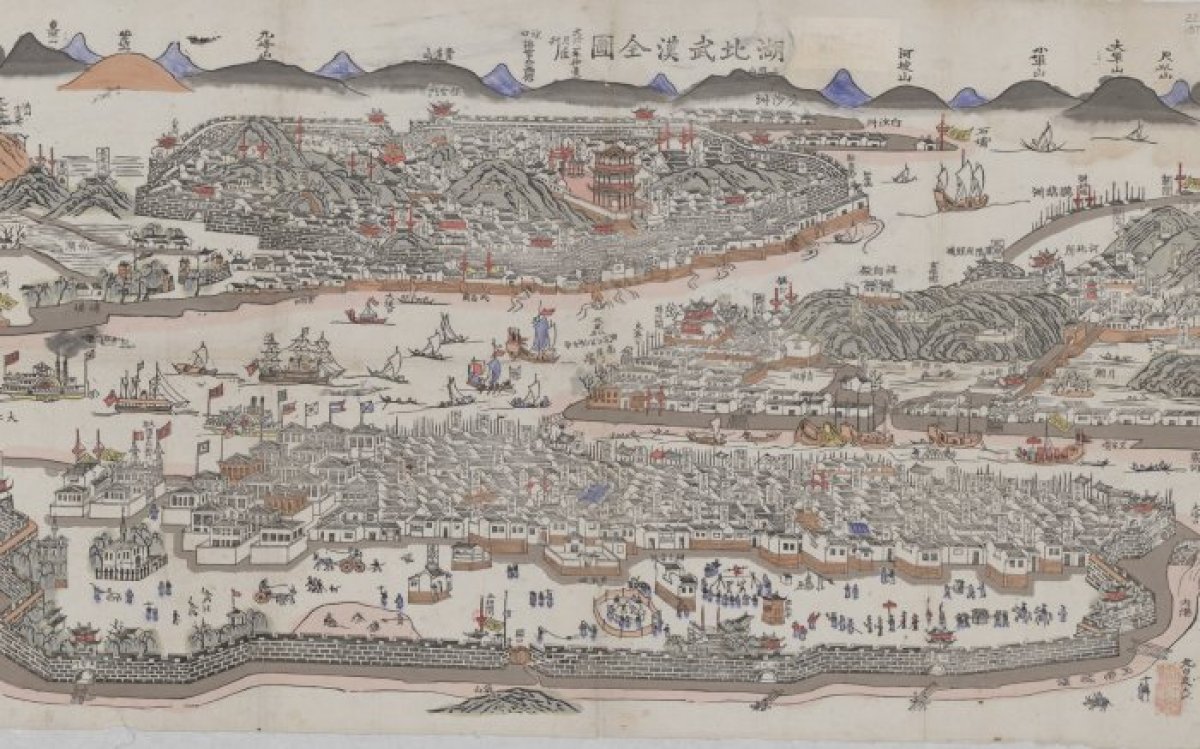

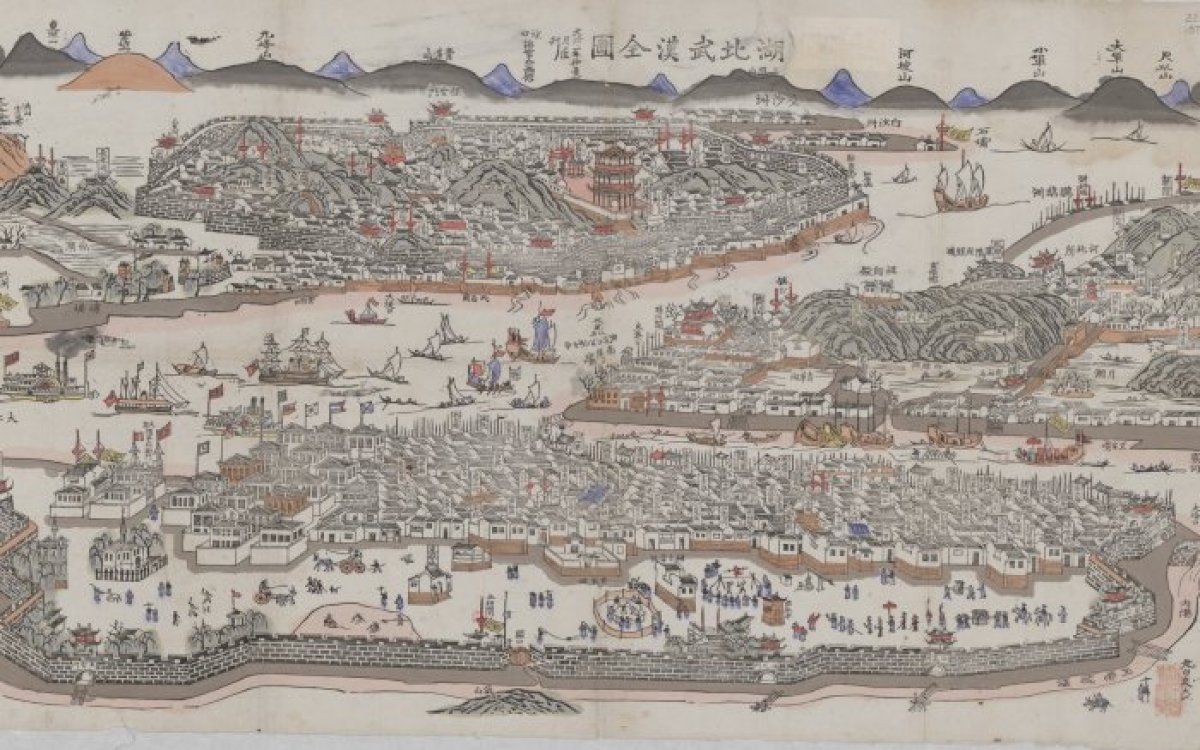

Map of Wuhan, Hankou: Gallery in the Studio of Ocean Clouds 1876, National Library of China

China in the late nineteenth century was a country undergoing rapid change. This was due in no small part to the opening of the treaty ports. Some of these were located deep inland, like Wuhan, bringing an unprecedented level of direct contact between members of the local population and foreign merchants.

Wuhan is an amalgam of three cities, Hankou, Hanyang and Wuchang. It lies on the Yangzi River among a network of waterways nearly 1,000 kilometres from the sea. Hankou became a treaty port in 1861 following the Second Opium War, and this then opened inland China to foreign trade.

This woodblock print map depicts the city of Wuhan in 1875, less than two decades after the establishment of foreign concessions, visible at the bottom left. The map looks east across the Yangzi, which bustles with Chinese and foreign shipping. Temples and streets throughout are named, providing the modern viewer with ample signposts for navigation. Hankou lies in the foreground, with Hanyang to the right separated by the Hanshui River, a major tributary of the Yangzi.

Across the water is Wuchang, its walled interior dominated by the Yellow Crane Tower. A building of this name has existed in Wuchang since the third century, although the one depicted here is neither the original of the Three Kingdoms period nor the one that can be found in the Wuchang district today.

China in the late nineteenth century was a country undergoing rapid change. This was due in no small part to the opening of the treaty ports. Some of these were located deep inland, like Wuhan, bringing an unprecedented level of direct contact between members of the local population and foreign merchants.

Wuhan is an amalgam of three cities, Hankou, Hanyang and Wuchang. It lies on the Yangzi River among a network of waterways nearly 1,000 kilometres from the sea. Hankou became a treaty port in 1861 following the Second Opium War, and this then opened inland China to foreign trade.

This woodblock print map depicts the city of Wuhan in 1875, less than two decades after the establishment of foreign concessions, visible at the bottom left. The map looks east across the Yangzi, which bustles with Chinese and foreign shipping. Temples and streets throughout are named, providing the modern viewer with ample signposts for navigation. Hankou lies in the foreground, with Hanyang to the right separated by the Hanshui River, a major tributary of the Yangzi.

Across the water is Wuchang, its walled interior dominated by the Yellow Crane Tower. A building of this name has existed in Wuchang since the third century, although the one depicted here is neither the original of the Three Kingdoms period nor the one that can be found in the Wuchang district today.

1. Display this woodblock-printed map for your students. As a class, discuss the following (using the background information as a guide):

- What evidence of foreign presence can you see?

- Use the image to make a list of nations present in the port of Hankou at the time this image was made (1875).

- Locate Wuhan (including Hankou) on a modern map of China

- Discuss the concepts of concessions and extraterritoriality

2. Ask students to investigate the Treaty Port system in China, with particular reference to the Opium Wars. By the end of the Qing Dynasty in 1911 there were over 50 treaty ports throughout China. Allocate a major Treaty Port to students working in pairs. They will complete a small investigative task by answering the following questions as they relate to their allocated port.

- Where was the port located?

- Which treaty opened the port to foreign access? Was it as a result of the First or Second Opium War?

- Which foreign nations had a presence at the port?

- Identify your port’s strategic and commercial importance for foreign nations. What was traded?

- Are there any influences on the modern day city that might come from its history as a Treaty Port (cultural, architectural etc)?

The following Trove Lists contain excellent primary source material which may be useful in this task:

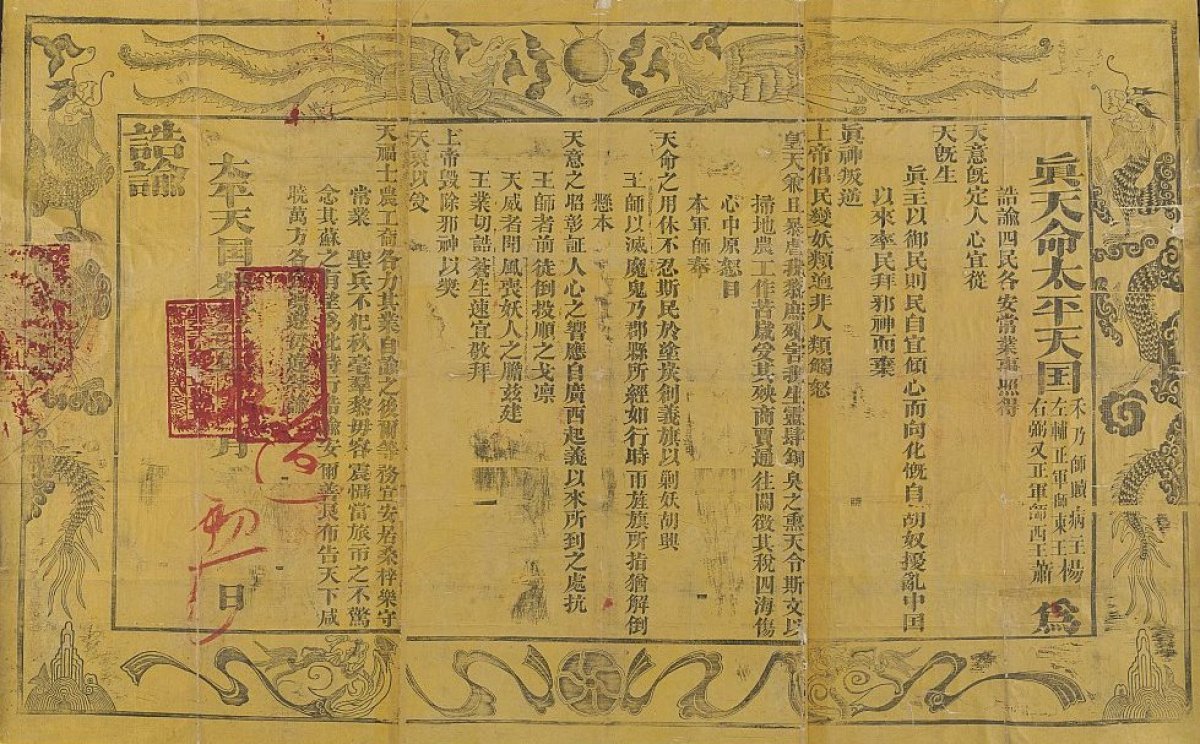

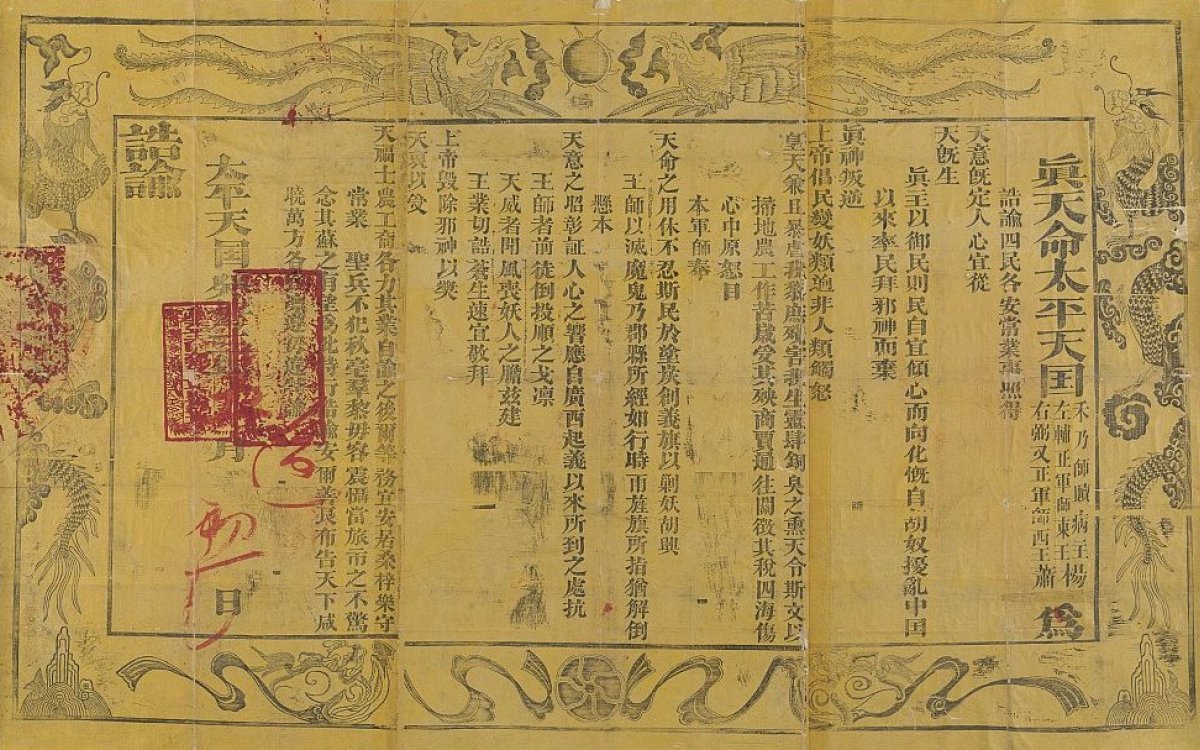

Yang, Xiuqing, -1856 & Xiao, Chaogui, -1852 & 楊秀清, -1856 & 蕭朝貴, -1852. (1853). Zhen tian ming Tai ping tian guo ... wei gao yu si min ge an chang ye shi / [Yang Xiuqing, Xiao Chaogui bu gao]. [Nanjing? : s.n.] http://nla.gov.au/nla.obj-61347334

[Transcription]

Yang, Henai Master, Disease-Dispelling Lord, Bulwark of the Left, Chief Commander and East King, and Xiao, Support of the Right, Chief Commander and West King of The Heavenly Kingdom of Great Peace under the True Mandate of Heaven hereby proclaim:

We enjoin all subjects to maintain their usual occupations. The minds of people should comply with the will of Heaven once it is established. The people should submit themselves in devotion once Heaven has given birth to the True Lord to reign over the people.

Since the barbarian minions threw China into turmoil, they have led the people to worship false gods and abandon the true God. They betrayed the Lord on High and incited the people to revolt. These demons are not at all human. They anger August Heaven and tyrannise and murder our people. They let the stench of cash permeate Heaven and leave our culture to languish in the dust. Farmers and craftsmen in their toiling suffer depredations year after year. Merchants in their trading are taxed at every pass. Everyone in the empire despairs; the entire central plain seethes with anger.

Our army upholds the mandate of heaven and cannot tolerate the torment of the people. We hoist the banner of righteousness in order to vanquish the demonic barbarians. We marshal our sovereign forces in order to exorcise these evil ghosts. We are like the arrival of timely rain for the commanderies and counties we pass. We are like relief in desperate times wherever our banners fly. We originate in manifestations of the will of Heaven. We are vindicated by the welcome of the people.

Everywhere we have been since the uprising in Guangxi, the vanguard of those opposing our sovereign forces has come over to join our ranks; all those fearing the might of Heaven have lost their demonic courage at news of us. We now establish our sovereign reign and command the multitudes to reverently worship the Lord on High and destroy false gods in order to encourage faith in Heaven and receive Heaven’s blessings. Officials, farmers, artisans and merchants shall all work at their occupations. From this proclamation onwards, you must live peacefully in your homes and engage happily in your usual occupations. Our holy troops will not cause the slightest harm. You should not be alarmed. When no traveller or trader takes fright, there will be hope of renewal. For this reason we make this proclamation to comfort you all. We announce this throughout the empire for all to know. Everyone should strictly obey without fail. This is a special order.

First day of the fifth month in the third year, guihao [6 June 1853], of the Heavenly Kingdom of Great Peace.

[Transcription]

Yang, Henai Master, Disease-Dispelling Lord, Bulwark of the Left, Chief Commander and East King, and Xiao, Support of the Right, Chief Commander and West King of The Heavenly Kingdom of Great Peace under the True Mandate of Heaven hereby proclaim:

We enjoin all subjects to maintain their usual occupations. The minds of people should comply with the will of Heaven once it is established. The people should submit themselves in devotion once Heaven has given birth to the True Lord to reign over the people.

Since the barbarian minions threw China into turmoil, they have led the people to worship false gods and abandon the true God. They betrayed the Lord on High and incited the people to revolt. These demons are not at all human. They anger August Heaven and tyrannise and murder our people. They let the stench of cash permeate Heaven and leave our culture to languish in the dust. Farmers and craftsmen in their toiling suffer depredations year after year. Merchants in their trading are taxed at every pass. Everyone in the empire despairs; the entire central plain seethes with anger.

Our army upholds the mandate of heaven and cannot tolerate the torment of the people. We hoist the banner of righteousness in order to vanquish the demonic barbarians. We marshal our sovereign forces in order to exorcise these evil ghosts. We are like the arrival of timely rain for the commanderies and counties we pass. We are like relief in desperate times wherever our banners fly. We originate in manifestations of the will of Heaven. We are vindicated by the welcome of the people.

Everywhere we have been since the uprising in Guangxi, the vanguard of those opposing our sovereign forces has come over to join our ranks; all those fearing the might of Heaven have lost their demonic courage at news of us. We now establish our sovereign reign and command the multitudes to reverently worship the Lord on High and destroy false gods in order to encourage faith in Heaven and receive Heaven’s blessings. Officials, farmers, artisans and merchants shall all work at their occupations. From this proclamation onwards, you must live peacefully in your homes and engage happily in your usual occupations. Our holy troops will not cause the slightest harm. You should not be alarmed. When no traveller or trader takes fright, there will be hope of renewal. For this reason we make this proclamation to comfort you all. We announce this throughout the empire for all to know. Everyone should strictly obey without fail. This is a special order.

First day of the fifth month in the third year, guihao [6 June 1853], of the Heavenly Kingdom of Great Peace.

The Taiping Rebellion lasted from 1850 to 1864 and was the major internal military challenge to the Qing dynasty in the 19th century. It was one of the bloodiest conflicts in human history, with more than 20 million people killed and 600 cities destroyed. The Taiping were led by Hong Xiuquan, a man who believed himself to be the younger brother of Jesus Christ.

This huge yellow poster with dragon motifs was acquired by the National Library of Australia in 1961 as part of the London Missionary Society Collection of old and scarce works sent back by missionaries to England from China.

Taiping forces captured Nanjing in 1853 and immediately set about transforming society in the lands under their control. This required that they communicate their aims and calm the people. This was done effectively through publications and banners such as these.

The fall of the Taiping Heavenly Kingdom finally came when the ‘Ever Victorious Army’ a contingent of Qing forces helped by foreign mercenaries was able to put down the rebellion using European military tactics.

Ask students to analyse the impact of the Taiping Rebellion on the Qing Dynasty:

- socially

- militarily

- and politically

The following Trove List contains excellent primary source material which may be useful in this task:

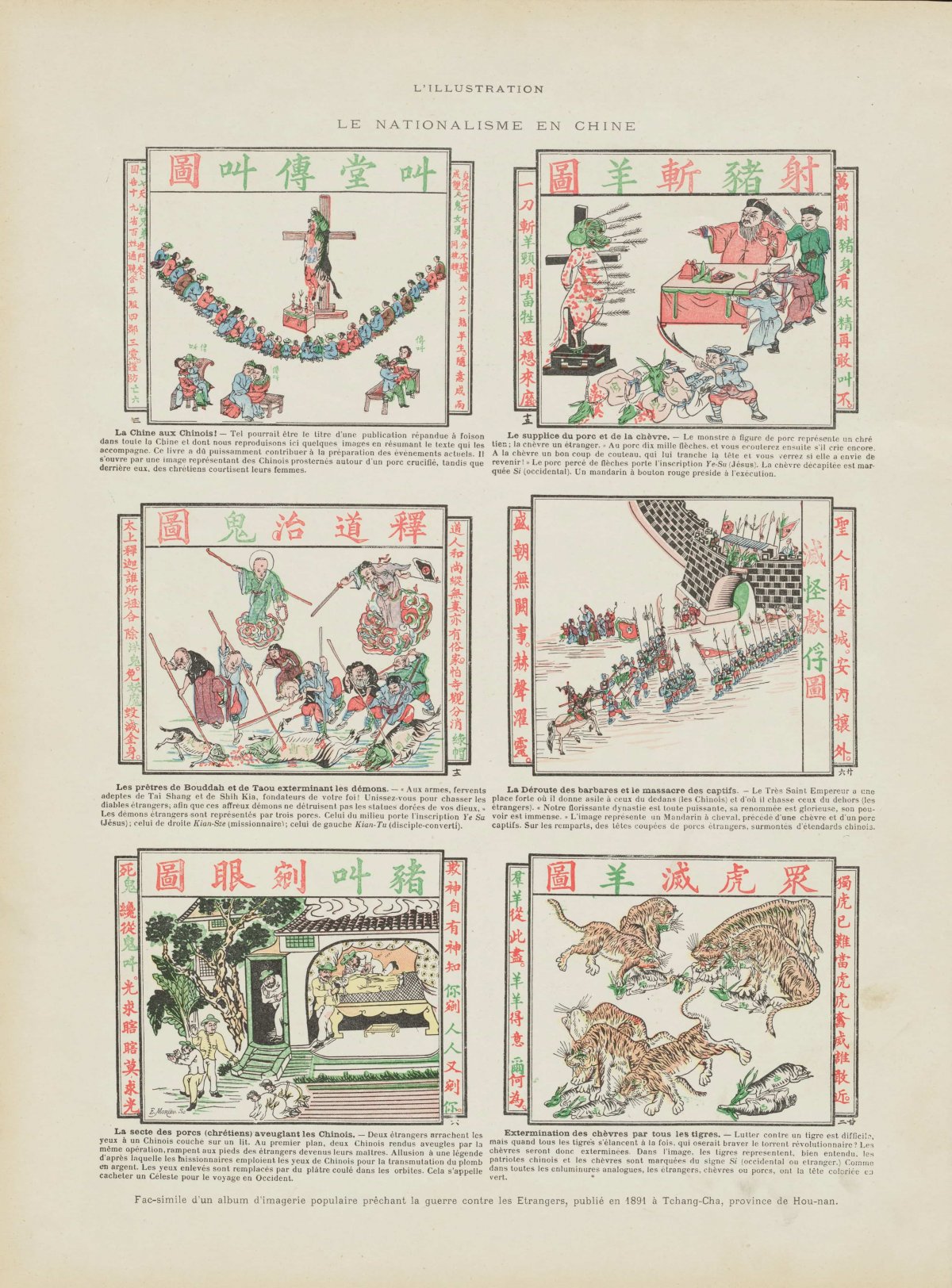

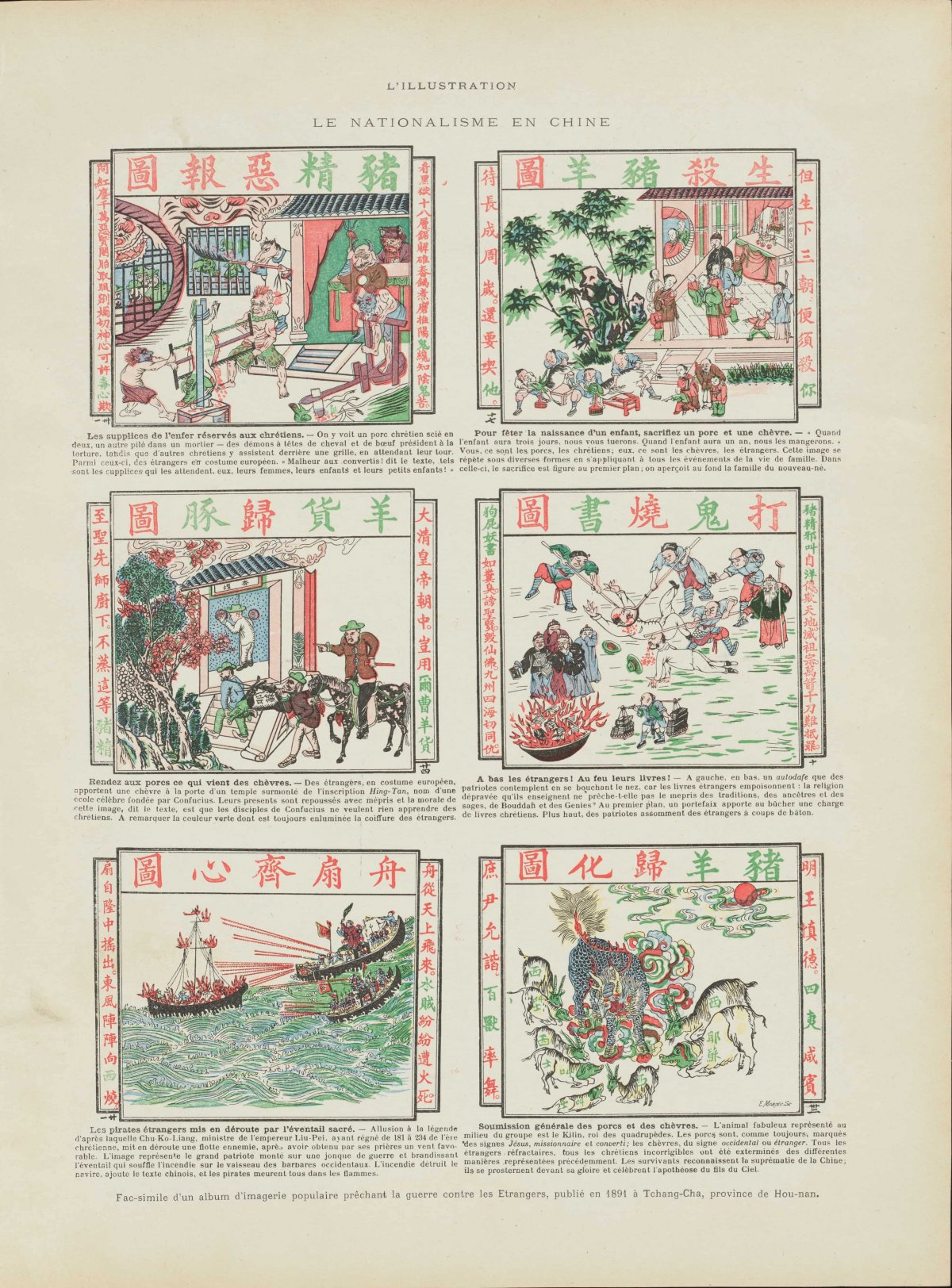

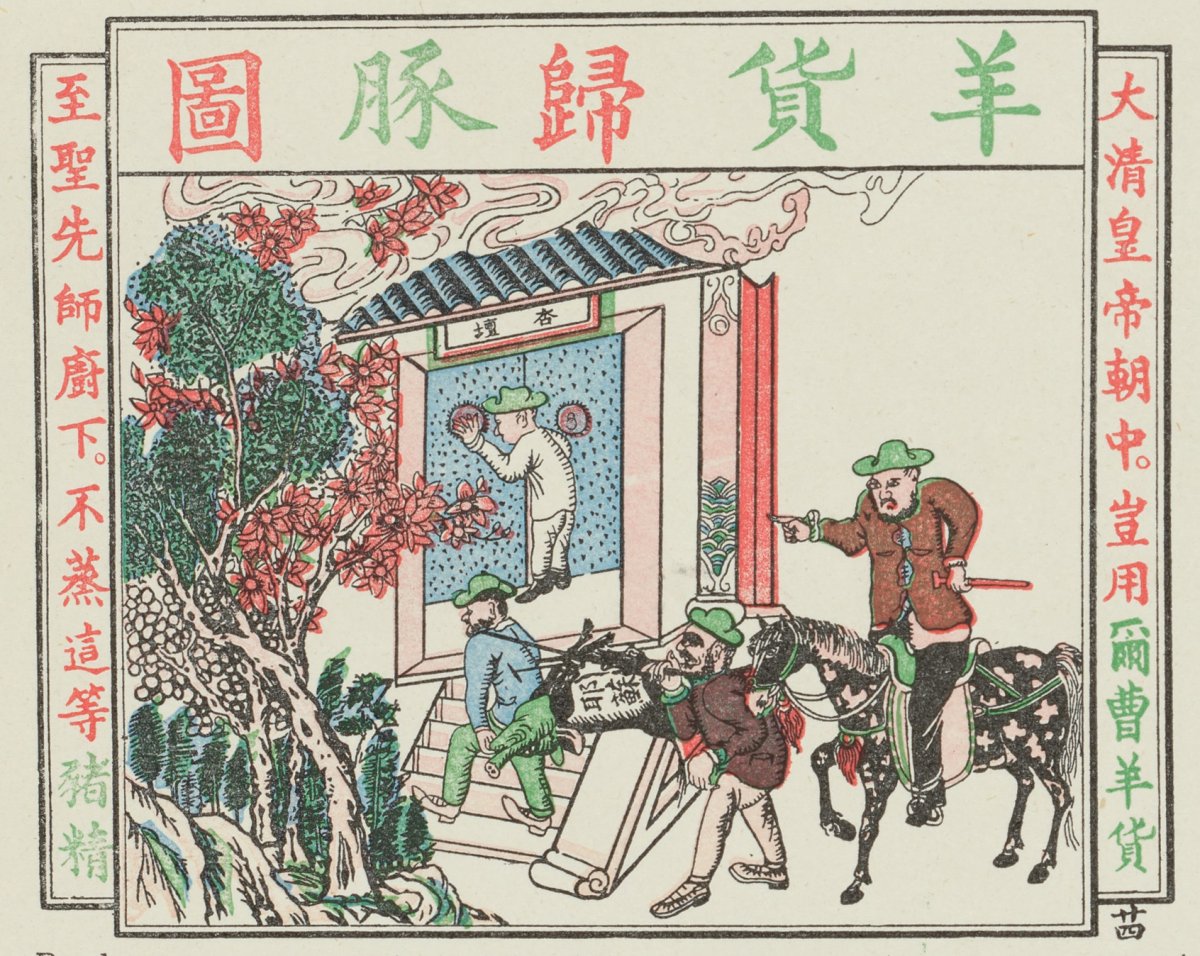

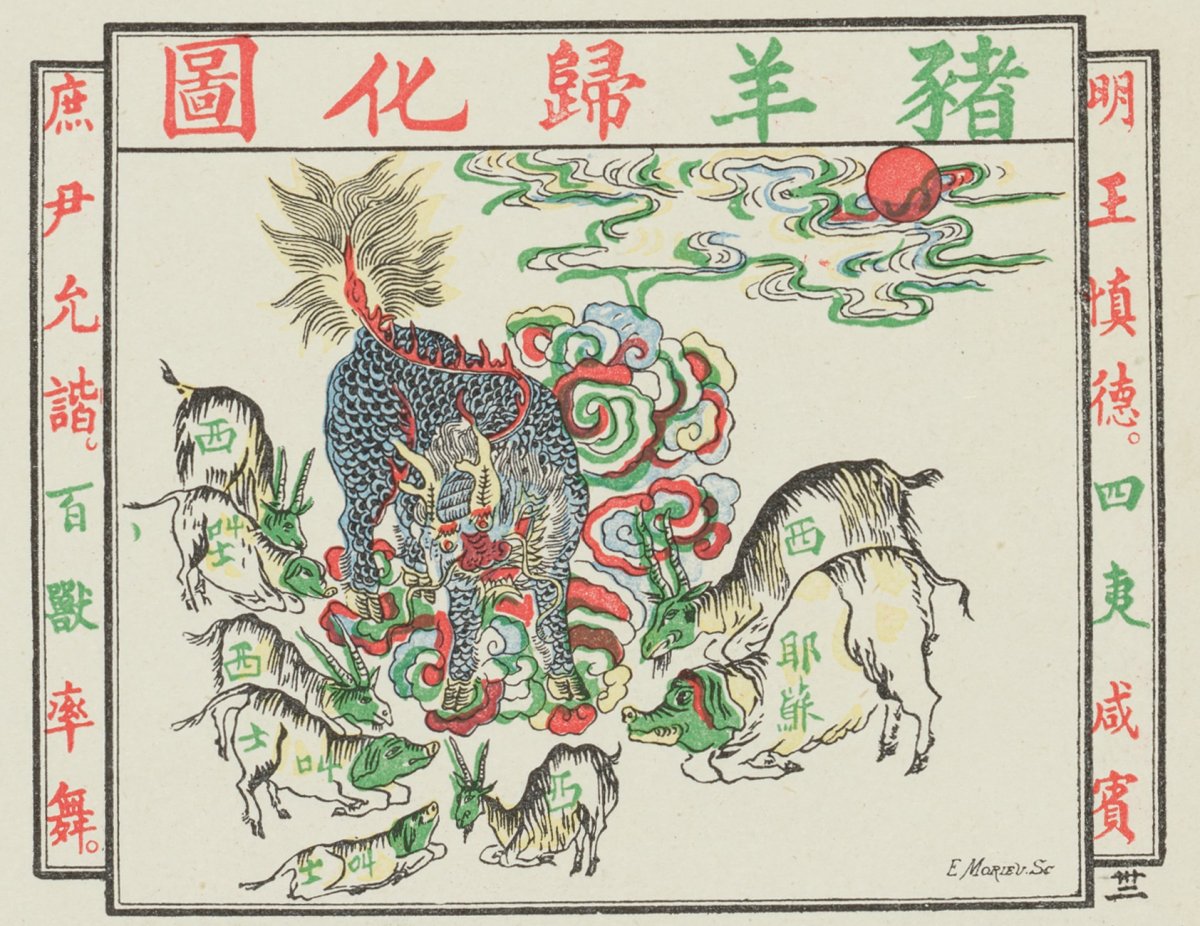

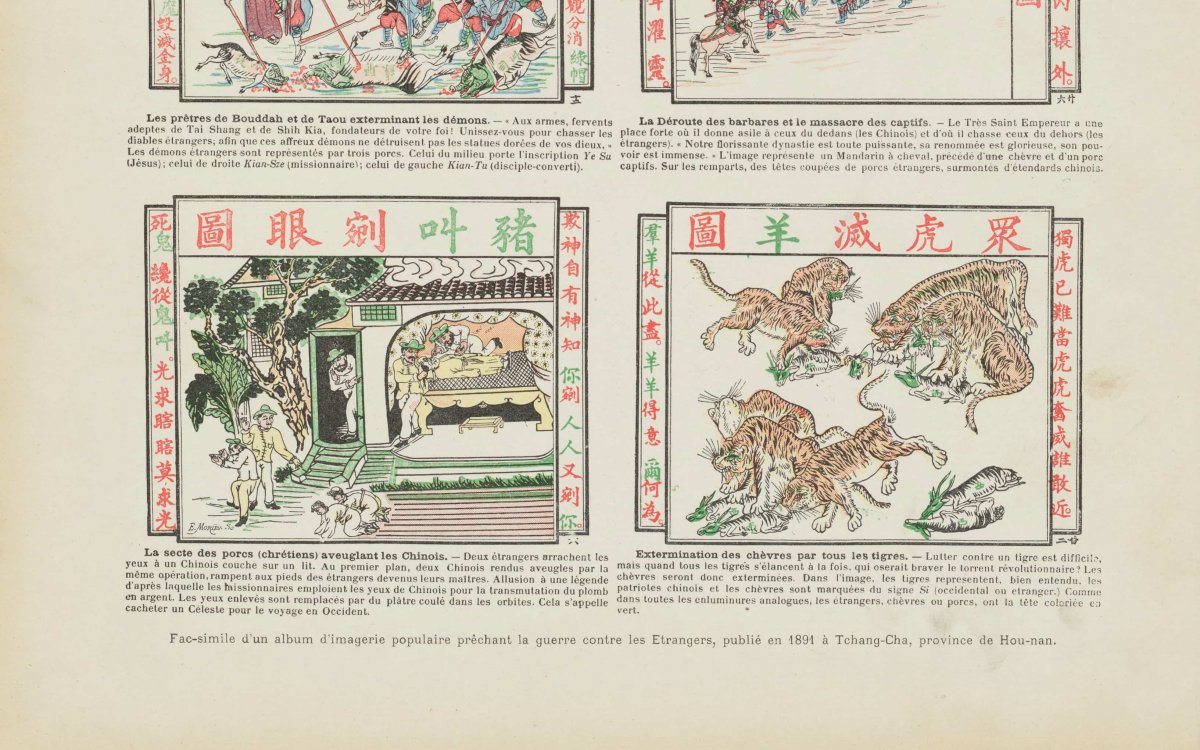

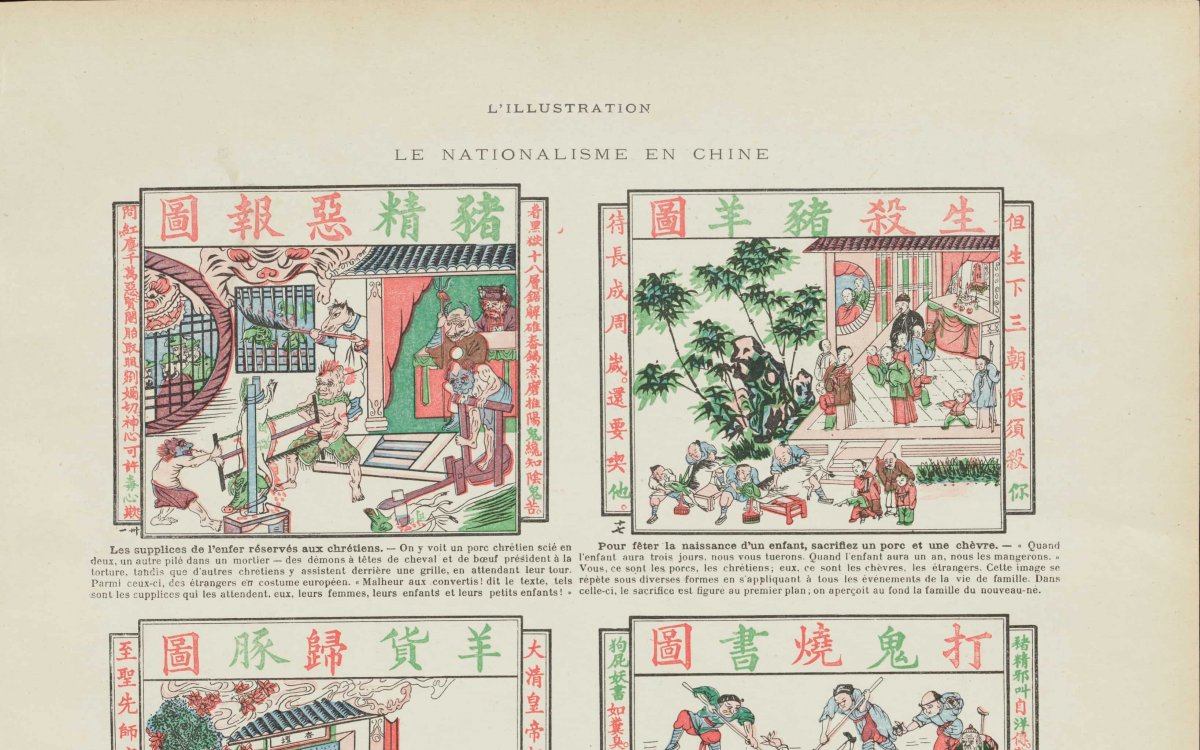

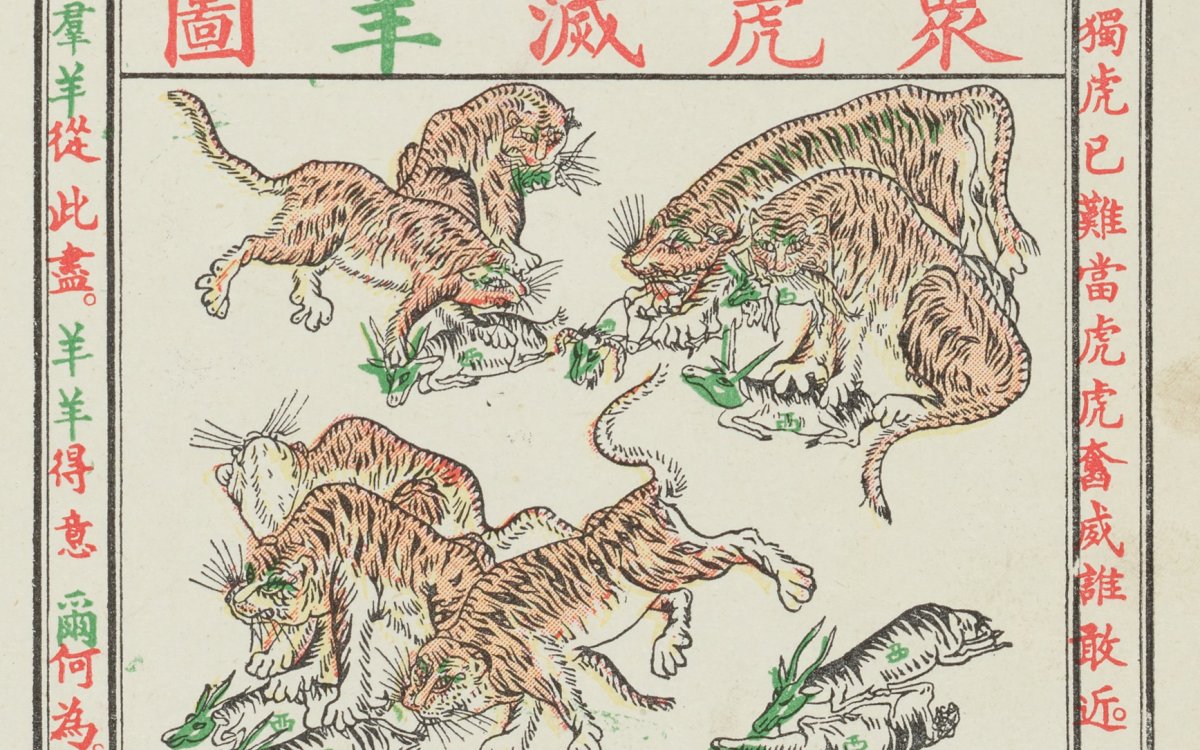

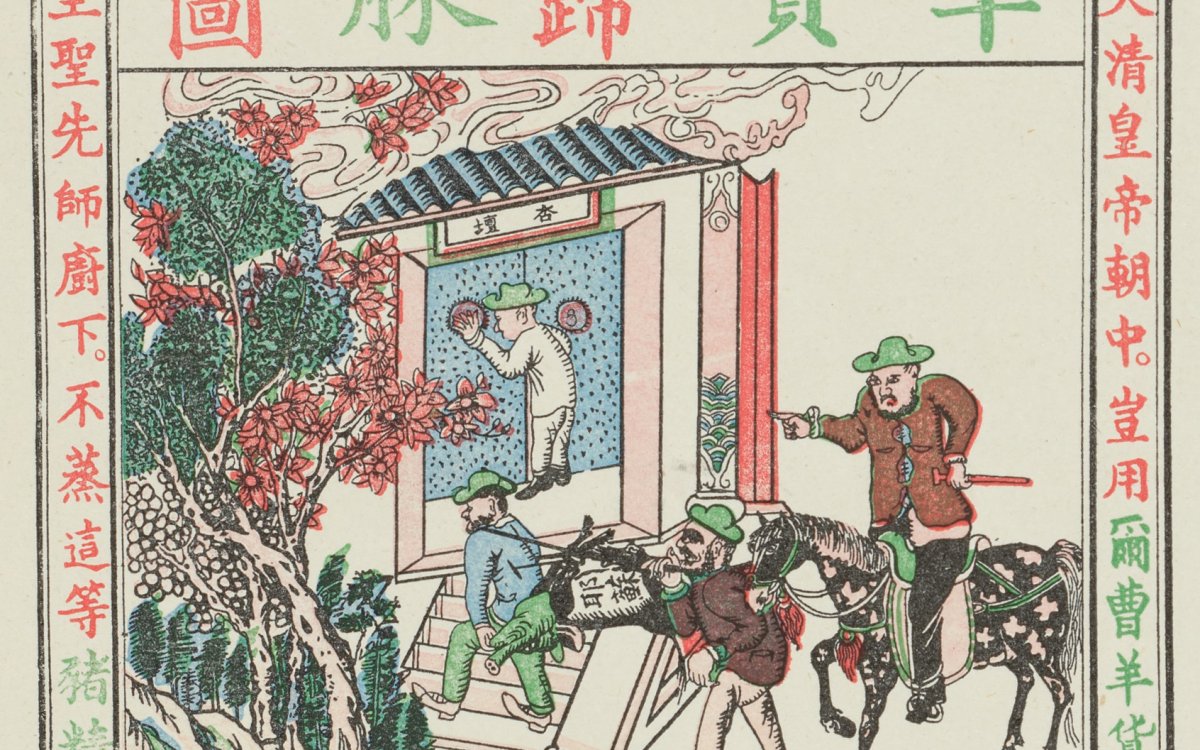

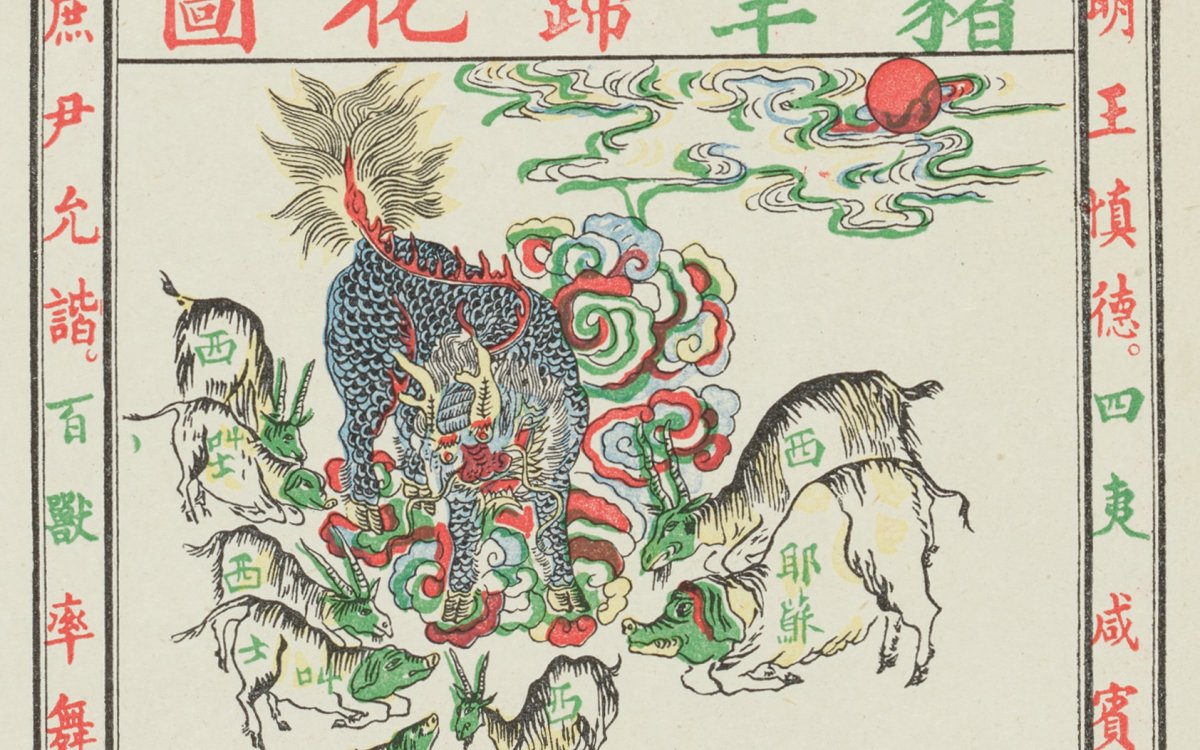

Zhou Han, Heresy Exposed in Respectful Obedience to the Sacred Edict c. 1891, Reproduced in L’Illustration, No. 2996 (28 July 1900) National Library of Australia. https://nla.gov.au/nla.cat-vn2538690

Zhou Han, Heresy Exposed in Respectful Obedience to the Sacred Edict c. 1891, Reproduced in L’Illustration, No. 2996 (28 July 1900) National Library of Australia. https://nla.gov.au/nla.cat-vn2538690

Zhou Han, Heresy Exposed in Respectful Obedience to the Sacred Edict c. 1891, Reproduced in L’Illustration, No. 2996 (28 July 1900) National Library of Australia. https://nla.gov.au/nla.cat-vn2538690

Zhou Han, Heresy Exposed in Respectful Obedience to the Sacred Edict c. 1891, Reproduced in L’Illustration, No. 2996 (28 July 1900) National Library of Australia. https://nla.gov.au/nla.cat-vn2538690

Zhou Han, Heresy Exposed in Respectful Obedience to the Sacred Edict c. 1891, Reproduced in L’Illustration, No. 2996 (28 July 1900) National Library of Australia. https://nla.gov.au/nla.cat-vn2538690

A Chinese book attacking the foreign presence in China represented Europeans as ‘pigs’ and ‘goats’, homonyms for ‘Catholic’ and ‘Western’ respectively.

A Chinese book attacking the foreign presence in China represented Europeans as ‘pigs’ and ‘goats’, homonyms for ‘Catholic’ and ‘Western’ respectively.

The Boxer Rebellion was a grass-roots, anti-foreign movement that started in Shantung Province in 1898 and spread through much of northern China. In English they were called ‘fists of righteous harmony’ and its motto ‘preserve the dynasty, destroy the foreigners’. Adherents practised martial arts, performed rituals designed to make them invulnerable to weapons and swore to destroy Christian converts. Its origins lie in the decline of the Qing dynasty and the series of humiliations and defeats by foreign powers. The Boxers had the support of many at court including the Empress Dowager Cixi and the imperial troops. The foreigners in Peking were slow to realise their danger until a month before being given 24 hours to leave the foreign legation quarters in Peking. The first international relief force was turned back. The siege was broken after two months by a foreign force of 20,000 troops and the city was looted. The Empress Dowager fled with the Emperor. They returned only after the terms of the peace had been signed. The foreign allies squabbled over the spoils but China had to pay a huge indemnity. Many thousands of Christians were killed.

The following Trove List contains excellent primary source material which may be useful in this task: