Constitution Day, 9 July 1900

On 9 July 1900, from her desk in Windsor Castle, Queen Victoria signed our Constitution into law with the Royal Commission of Assent 9 July 1900 (UK). With this document, Australia was able to federate on 1 January 1901 and become the Commonwealth of Australia, with our new royally assented Constitution as our governing guide.

If any of you have read, or tried reading, the Constitution of the Commonwealth of Australia, you will know it is a boring read. Unless, of course, you’re a constitutional lawyer or Justice of the High Court, in which case, it definitely tickles your legal fancies.

For this historian, however, it is Section 51—what I call the ‘weird and wonderful’ section—that interests me. Back in February, my colleague wrote a blog post about the digitisation project of the Library’s poster collection, and as I browsed the finding aid for that collection, I discovered some interesting Section 51 themed posters to share with you. Students and teachers of ‘civics and citizenship’, here come some excellent constitution-related primary sources.

Meet Section 51 of Our Constitution

Section 51 is the bit of the Constitution I call the not boring section and, for the citizens of Australia, it is the most important as it empowers the Federal Parliament ‘to make laws for the peace, order and good government of the Commonwealth’. (Commonwealth of Australian Constitution Act 1900 (Cth), Section 51, nla.cat-vn3768047)

Section 51 includes the areas of trade and commerce, taxation, quarantine, banking, what I call The Castle law—‘the acquisition of property on just terms’—,, immigration and emigration and influx of criminals.

The latter was inspired by the ‘swarms of convicts and ticket-of-leave-men from other settlements [who] invaded the colony [of Victoria] and became a nuisance and menace to its peace and welfare’ during the goldrush. (See the annotated edition of the Constitution by misters Quick and Garran, pp. 629-631.)

However, I want to focus on ‘fun’ laws that resulted in the production of the gorgeous posters in the National Library’s collection.

Section 51 (v): Postal, Telegraphic, Telephonic, and Other Like Services

Prior to federation, the mail systems of the 6 colonies operated independently to each other. The railways operated independently too, with each colony using different railway gauges, which meant having to change trains at the borders. That was until Section 51 (xxxii) and (xxxiv) empowered the federal parliament to get things choo-chooing uniformly across state lines.

With section 51 (v), the office of the Postmaster-General (PMG) was created and a national postal and communications system was developed. (For my fellow West Australians, the first PMG was federation father and the first WA Premier, Sir John Forrest.) Canberra’s East Block building (currently home to the National Archives) was the headquarters for the PMG when Parliament moved to the new Federal Capital City in 1927.

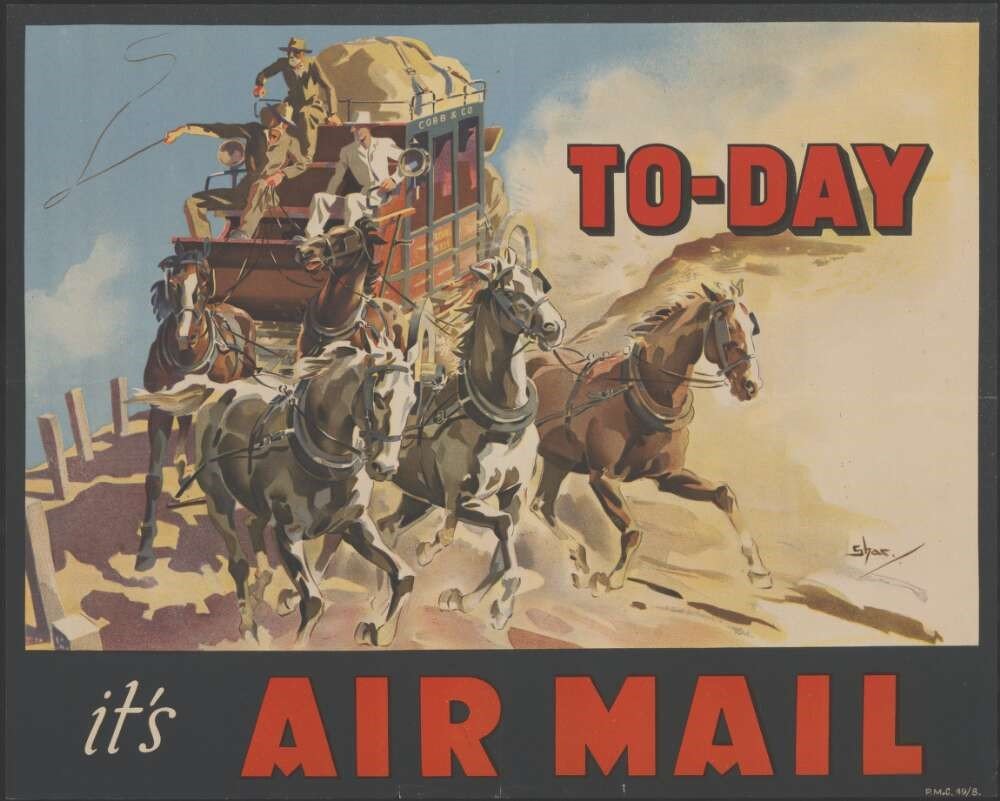

Like its fellow Section 51ers, Section 51 (v) has resulted in some fine posters over the years, including this nod to our colonial past to advertise the speed of the airmail postal service established in 1914.

Section 51 (vii): Lighthouses, Lightships, Beacons and Buoys

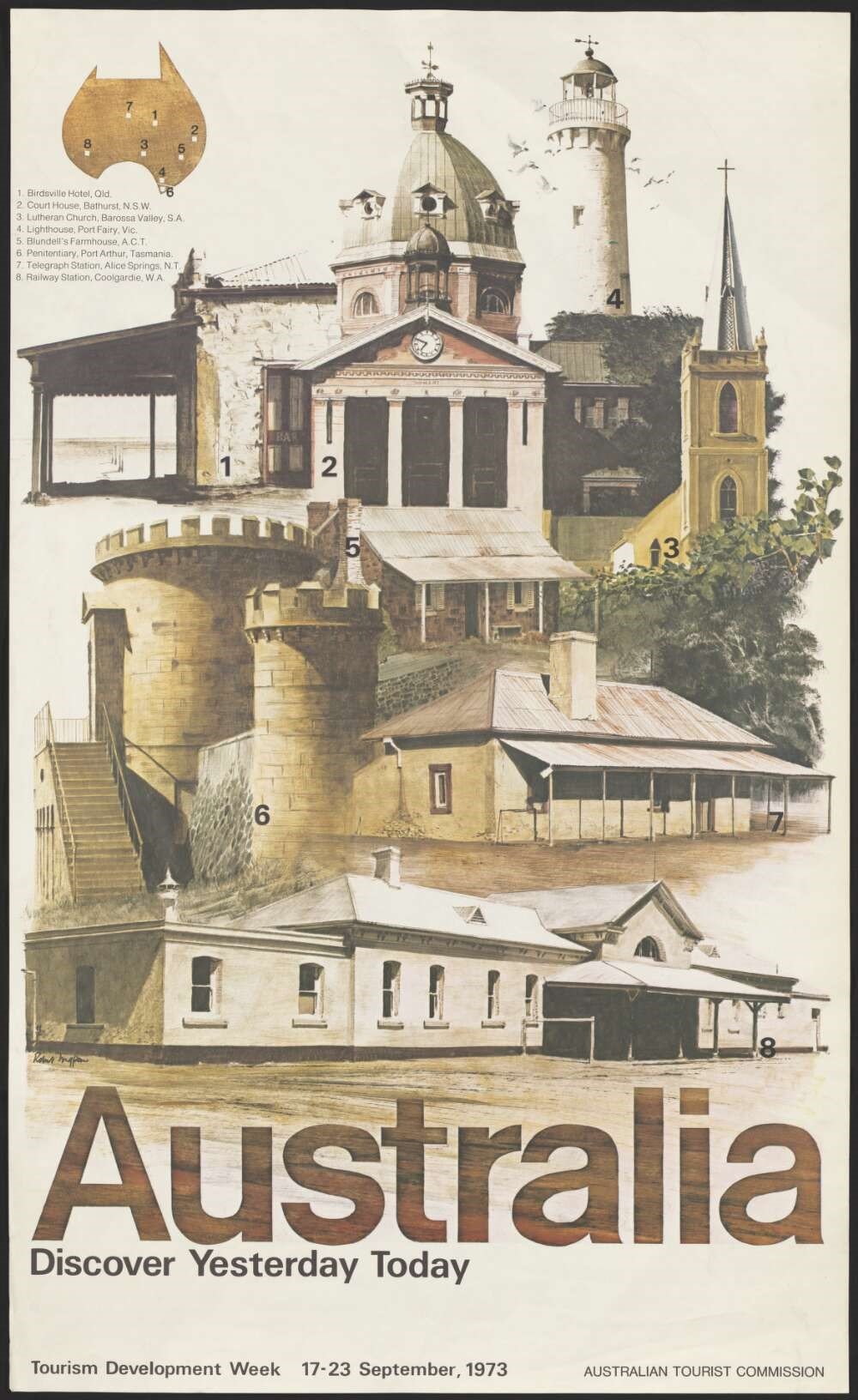

Who doesn’t love a lighthouse? Strange people, that’s who! I love this first poster as not only does it include a lighthouse, Victoria’s Port Fairy Lighthouse, but other buildings and institutions that embody Section 51—‘to make peace, order and good government of the Commonwealth’—and get the states connected.

Section 51 (xii): Coins, Currency and Legal Tender

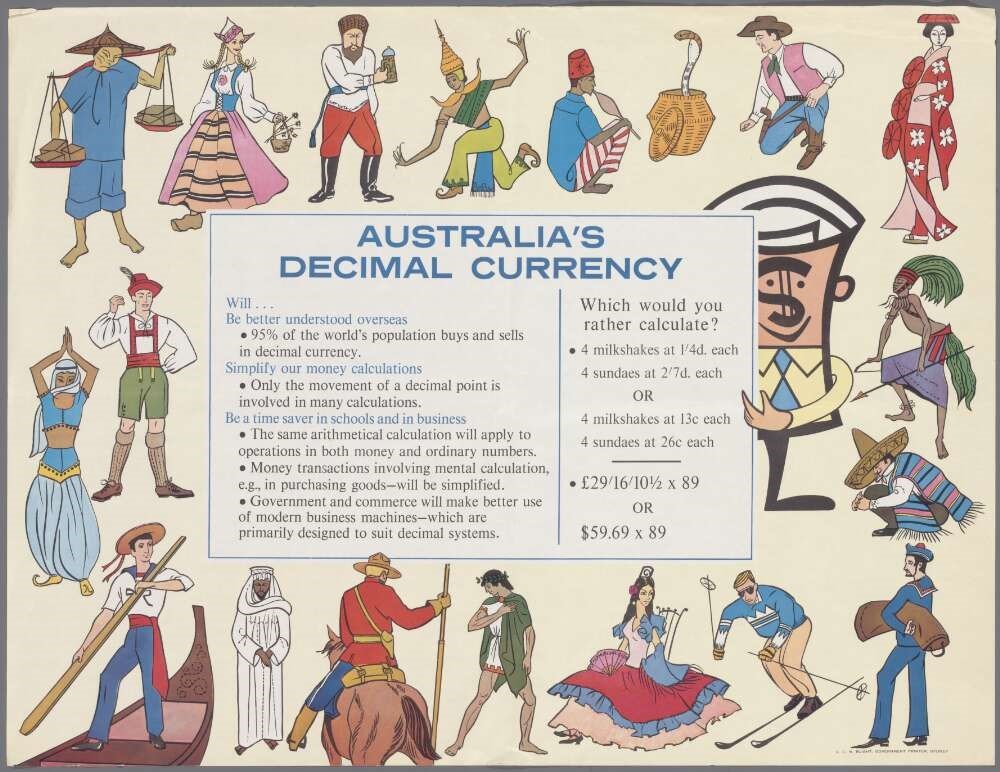

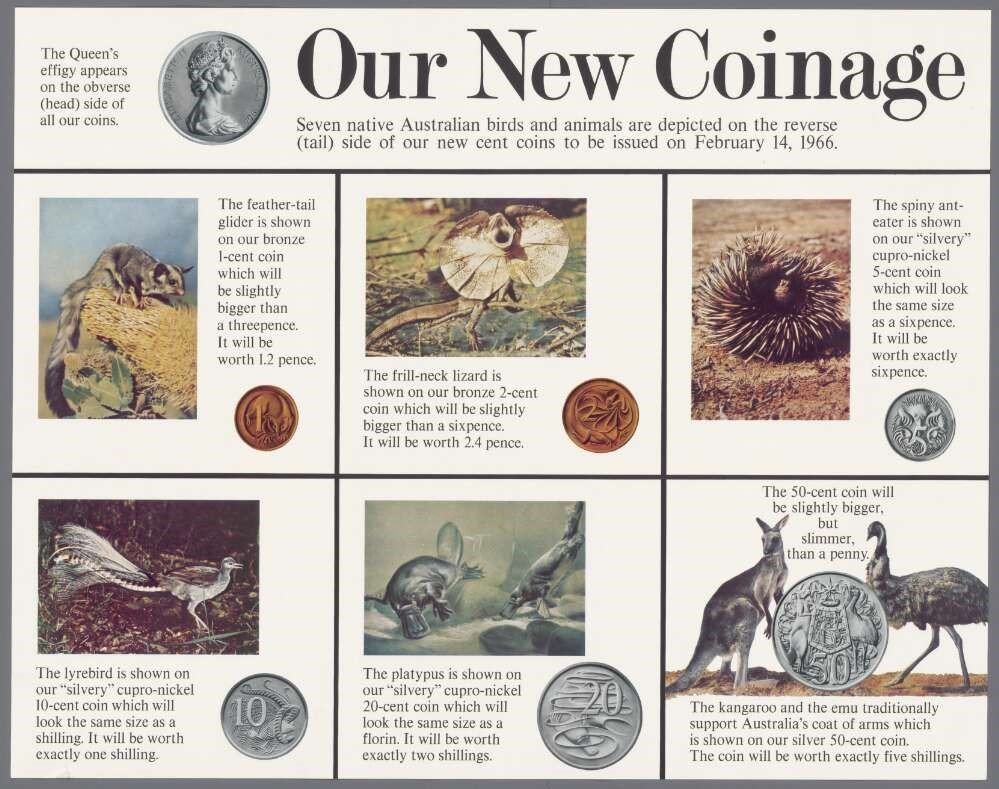

From 1788, Australia’s system of currency was pounds, shillings and pence, just like the United Kingdom. However, wielding the power of Section 51 (v), on 14 February 1966, the federal parliament converted Australia to ‘dollars and cents’. In addition to teaching aids for the classroom and a 48-page guide for citizens, the Commonwealth government released television advertisements informing Australians how the new currency worked, with a catchy jingle that I guarantee older readers will now be singing—‘in come the dollars, in come the cents’. And of course, there were posters to illustrate how to calculate decimally and to show what our notes and coinage looked like.

Section 51 (xv): Weights and Measures

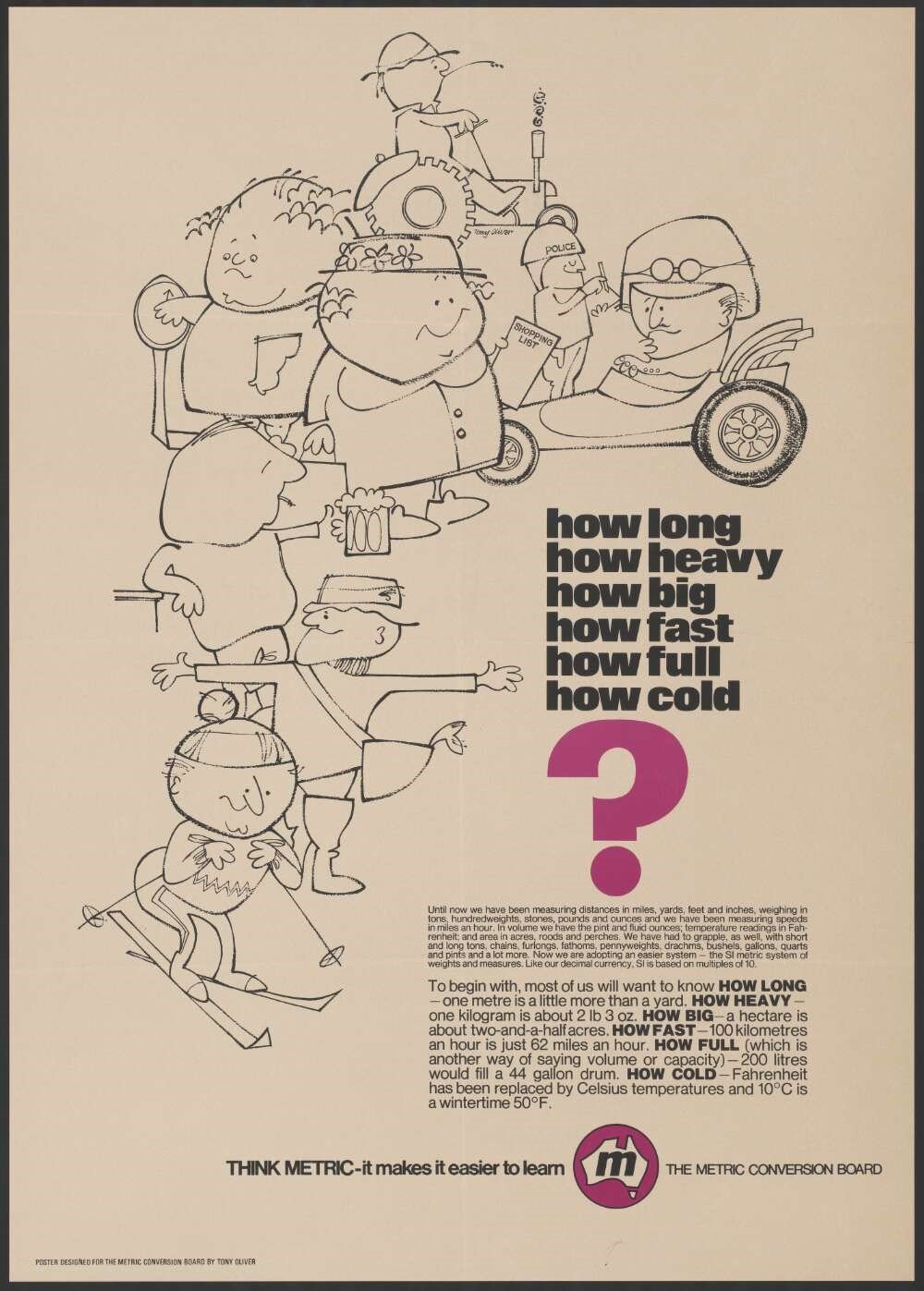

With the successful rollout of our new currency, and empowered by Section 51 (xv), 1970 saw Australia’s system of measurement change with the Australian Metric Conversion Act 1970 (Cth), taking us from the imperial system (miles) to metric, which, ironically, is miles better. (Bad historian joke.)

The rollout to the new metric system was a little slower (can we make a mileage joke here?) than our currency conversion. The Act was passed on 12 June 1970 and the Metric Conversion Board established the following month to start the ball rolling on the public awareness campaign. However, we didn’t go fully metric until 1988. Guides and advertisements were produced, the former without a catchy jingle, with many focussed on what it meant for speed limits on our roads. An 18-page guide, Metric Conversion and You, was posted ‘To the householders’ of Australia and, again, posters appeared in post offices, banks and schools across the country.

Note: The catalogue entry for this poster suggests a date of 1963, however, as the Metric Conversion Board was not established until 1 July 1970, this poster is likely from the 1970s.

So, that’s a few of my favourite examples of our Constitution’s Section 51 in action. There are so many others, and I particularly love the ones relating to trade and commerce (i), and not just because there are lovely posters of chocolate.

I encourage you to have a browse through the National Library’s Australian advertising poster collection, which is a much pleasanter way to get to know our Constitution than reading it.

Further reading and primary source links

For students and teachers, the National Library’s Digital Classroom has a wealth of curriculum-linked resources on the constitution, federation and more.

For other readers like myself, who are attempting to make up for their lack of ‘civics and citizenship’ studies back in their school days, the Digital Classroom is also an excellent resource to fill in the gaps, and fool one’s children into thinking you know exactly what you’re talking about when assisting with homework.