'Governess Wanted', The Courier (Hobart), 28 June 1848, nla.news-article2968730

For educated middle-class women in 19th-century Britain, options were limited. Marry and bear children, accept the drudgery of keeping house for relatives or friends, or attempt to find a position in one of the few industries that would employ women. In her new book, Great Expectations: Emigrant Governesses in Colonial Australia, Dr Patricia Clarke OAM tells the story of a group of intrepid women who found a different solution, on the other side of the world.

Teach your protégés to emigrate; send them where the men want wives, the mothers want governesses

—Maria Rye, founder of the Female Middle Class Emigration Society

To mark the book's launch, Patricia sat down for a chat with Kathryn Favelle, the Library’s Director of Community Engagement.

Patricia Clark in the National Library Bookshop with copies of Great Expectations: Emigrant Governesses in Colonial Australia, 2020.

Congratulations, Pat, this is a wonderful read, particularly at a time when we’ve all been thinking about homeschooling, and many of us have had our children home over some part of the year. It’s really lovely to dip back and see how learning was done in the 19th century. What led you to write a book about colonial governesses?

Well, I came across the letters of a group of emigrant governesses in the National Library when I was researching my great-grandmother. I’d always been intrigued by how she could possibly have kept her children after being widowed in Adelaide in 1870, so I was looking for ways that women could earn a living and I came across these letters.

And I was immediately diverted from my great-grandmother to these letters because, whereas only I really would be interested in my ancestor, I knew these letters would make a good book.

It is an intriguing story. The letters all came from one source, the Female Middle Class Emigration Society. What was the society trying to do? What was it set up to do?

It was founded by Maria Rye and she saw that there was a huge problem in England. There was a surplus of women – all women, but educated women in particular, and there was such a small range of jobs open to them. What could they do? There were no office jobs in those days or very few.

Maria Rye herself started a law-copying business, employing women to copy legal documents, but in general, governessing was the job open to educated women and there was a surplus of women. Also the marriage prospects were not that good.

So she began this society to help them to migrate to British colonies, and quite a lot came to Australia under this scheme.

It seems such a brave and crazy thing for a single woman to be doing at that point in time, a long sea voyage. Did you find that the women were a particularly brave and bold lot or was the need to find a way to earn a living a real driver for them?

I think the need to earn a living was the main driver. They had to have a certain adventurous spirit to leave their homes usually forever but migration was fairly usual in Britain at that time. But what the society did for them was offer them a way of coming here with some protection.

It arranged the shipping for them, cabins on ships for them, it gave them advice on what to take, the references they would need when they got to Australia and they set up what they called colonial correspondents. These were fairly important people in colonial society who set up committees to help the women when they arrived. In fact, these committees didn’t do nearly as much as people thought they might because they were very busy people themselves, but it was a great help.

Were the women coming to jobs that they knew existed or did they arrive and then had to find work through the contacts that the committees were providing?

Only very few came to jobs that had been arranged. A couple were arranged on the ship with the colonial families coming back from, say, a trip to England. That was quite an achievement for the governess concerned.

A few were engaged before they left England but generally they were thrown on their own resources once they arrived and they had to have enough money to keep themselves until they got a job, to stay in a governesses’ home or a hotel somewhere.

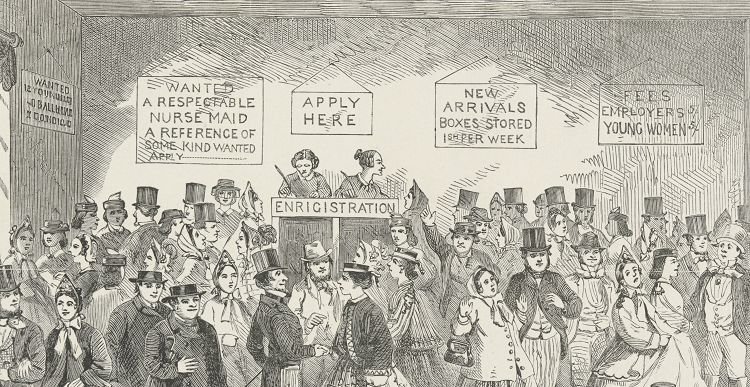

Some even had to advertise when they didn’t get jobs through the society’s contacts.

'Governesses were led to believe that well-paid jobs would be waiting for them in Australia but instead found a highly competitive market in which only the well qualified could compete.'

Scenes and Sketches in Australia, The Labour Office, c.1860, nla.cat-vn230793

Your book is full of fascinating individual stories. Were you able to find out what happened to these women at the end of their governessing careers?

It’s much easier now than it used to be. There’s still the search of marriage, births and deaths records but it has become a lot easier with the availability of all these records online. I was also able to follow in much more detail, than I had been [able to] years ago, the people who employed them, and this was very important in widening the scope of the book, in bringing [together] the lives of those people.

Some were in cities – perhaps a professional family [or] father. It used to take a week to get to some of the places they went to and this is places you’d get to in less than – well you get in the car and go now. One of them was actually on the Victorian-South Australian border in the Wimmera.

What was her story?

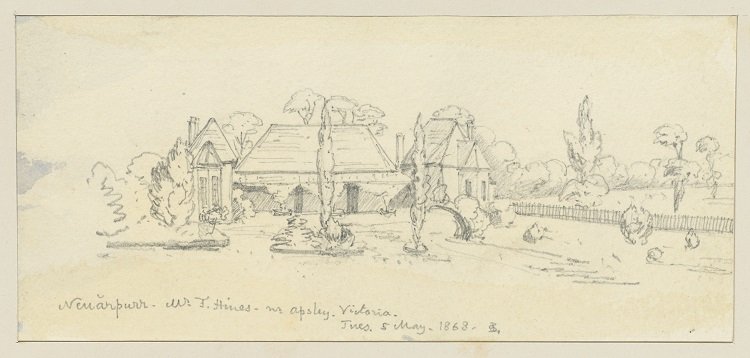

Louisa Geoghegan was the daughter of an Irish doctor and she was one who had a job arranged. She met the people as she got off the boat, the Hines family from Neuarpurr – that was the name of the huge property. She travelled with them. She went by train to Ballarat and then into the horses and cart and it took them a week from there, from Ballarat to get very close to the border of South Australia and a tragedy happened on the way.

They got to a relative’s place that was just before the next huge property and the girl that was to be her main pupil got measles and very, very sadly died aged 12 so her whole appointment started off in these tragic circumstances.

'Louisa Geoghegan described working at Neuarpurr, the remote property of the Hines family near the Victorian–South Australian border, as "a mixture of roughing and refinement".'

Stanley Leighton, Neuarpurr near Apsley, Victoria, 1868, nla.cat-vn2132866

These women were much more intrepid than I think we sometimes think colonial women were. This is your 14th book, and so much of your work is about uncovering women’s lives. Why have you focused on colonial women in a lot of your research?

I suppose that I began and one led to another in a way. I’m into the 20th century now, I might say but I was in the 19th century quite a lot and that really stems from having been a journalist and been very interested in the way women broke into journalism and writing. And I wrote several biographies of women writers, journalists. Journalism was a way that women became writers, became known, writing serials and colonial papers and then being accepted as novelists, really, or writers.

There seemed to be a much wider range of employment for women than perhaps we assumed there was. Do you think that’s true or am I just making that up and being wishful?

Certainly [in] the second half of the 19th century, jobs opened up enormously and it became more usual for unmarried women to get a job. By the 1880s, shops were great employers of women and a lot of women became bookkeepers.

One woman who came here as a governess and couldn’t get a job as a governess took a job on a country property as a bookkeeper, so they were versatile and had skills to fit in, some of them.

One of the things that struck me about this book was that when you were writing it, you had no idea that we would be facing a pandemic, and that people would be having to homeschool or help their children learn from home. Are there things that we can learn from the governesses about homeschooling and home-learning?

Well, I think anyone who’s homeschooling at present, or has been, would welcome a governess. They could take over the children and of course in the days when governesses were common, families were quite big. Some of them taught six students – six children from say the ages of 5 to 18 – and [a] great range of subjects. They would be a boon to homeschooling [caregivers] these days. I don’t know that their discipline would be as welcome now as maybe it was then!

There was great emphasis on learning to play the piano and practise which was fairly strictly enforced. Children maybe, I’m not sure, maybe learnt a smattering of more languages then but I think they would have been very short on maths and science although some governesses would take the children out in the bush and draw, very planned – [drawing] was regarded as one of the things that cultivated women [should] be able to do.

'Drawing and painting were valued accomplishments and governesses who could teach these subjects were well paid.'

Betsey Wright Nairn, Painting Class (detail), c.1845, Alexander Turnbull Library, Wellington, New Zealand, E-444-q-075

Pat, history often gives us the very big picture, the huge arc – the Great War, the Great Depression. In works like Great Expectations, you zoom in on the individual life of a person or a family and show us the past in a different way. Why is it so important for us to look at those individual lives?

Individual lives just – they’re like a root into the life of an individual, what that person was doing at this particular moment in history. They might be going out to walk in the bush, they might be catching a tram, they might be going to a shop and what are they buying? They might be buying a piece of music. It all adds up to creating this whole colonial society, so that it’s quite different from reading about an era in history, what the government was doing, what was happening in particular towns or locations.

It’s quite a different perspective and I find it fascinating, I like that sort of immediate feeling of this is a picture of life then. If you get a lot of lives, they all add up to this colonial society. With individual biography, it’s the life of that person and her interaction with other people. It also opens up this whole range of society.

About Dr Patricia Clarke OAM

Dr Patricia Clarke is a writer, historian, editor and former journalist, who has written extensively on women in Australian history and the history of journalism. In 2001, she was awarded the Medal of the Order of Australia for services to Australian history, and she is an honorary fellow of the Australian Academy of Humanities. Great Expectations is her 14th book.

You can learn more about Patricia Clarke's extraordinary career by having a look through her personal papers, which include correspondence, drafts and research material relating to her books. To locate a specific item, try using the Guide to the Papers of Patricia Clarke.

About the Book

For educated middle-class women in nineteenth-century Britain, options were limited. Great Expectations: Emigrant Governesses in Colonial Australia is the story of a group of intrepid ladies who forged a different path—as governesses to wild colonial boys and girls on the other side of the world.

Great Expectations (NLA Publishing, 2020) is available now in the National Library Bookshop and through selected retailers. To receive a 10% discount* on your copy, purchase through our online shop and use the code SPOONFULOFSUGAR at the checkout.

*Offer exclusively online; for local collection, please select pick up instore at checkout. Offer ends Wednesday 28 October. No further discounts apply.