James Cook commanded three Royal Navy voyages to the Pacific between 1768 and his death in Hawaii in 1779. They were scientific and strategic in nature, and extensive documentation was vital to their success. Artists travelled on all of them, and they produced invaluable records. The National Library of Australia’s recent exhibition Cook and the Pacific, on display until 10 February 2019, looked at Cook’s voyages as meetings of peoples and their knowledge systems. In a special way, the works of art from the voyages can transport us to those meetings and those places of the Pacific. This is the first of a three-part blog, an overview of the voyage art in the exhibition.

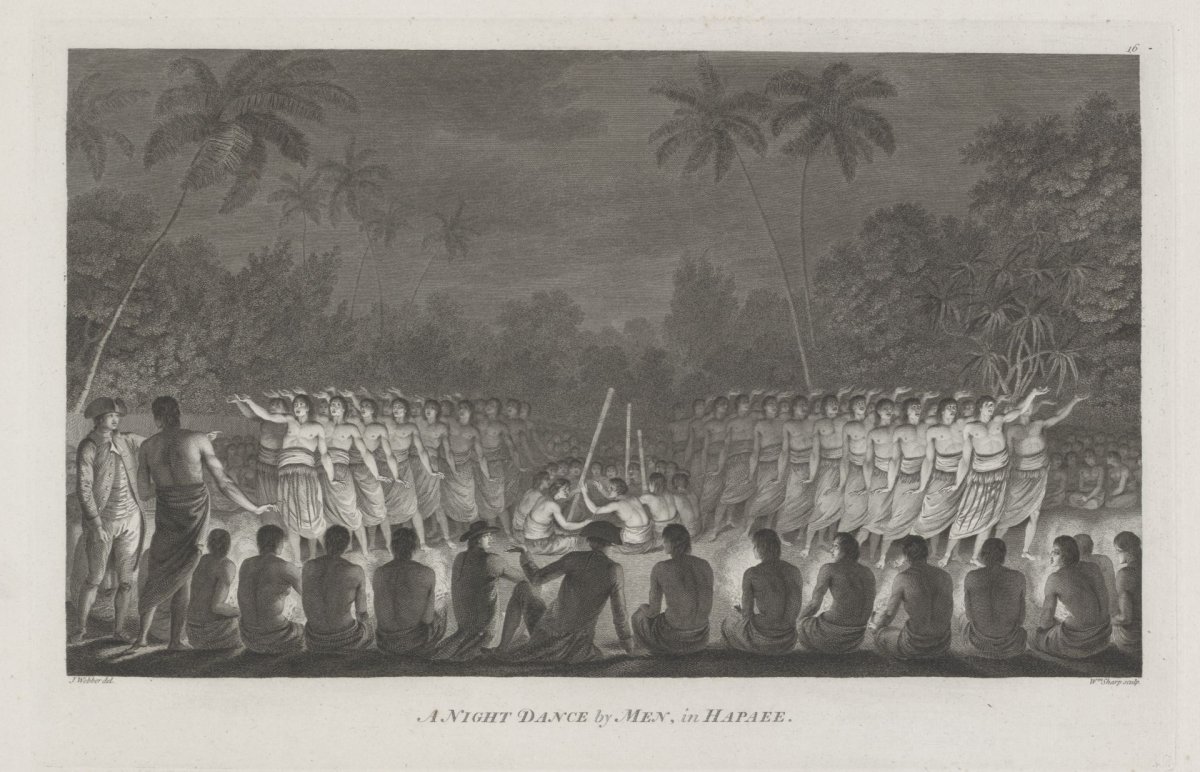

William Sharp (engraver, 1749–1824), after John Webber (artist, 1752–1793), A night dance by men in Hapaee 1784, engraving, National Library of Australia, Rex Nan Kivell Collection (Pictures), nla.cat-vn2098424

William Sharp (engraver, 1749–1824), after John Webber (artist, 1752–1793), A night dance by men in Hapaee 1784, engraving, National Library of Australia, Rex Nan Kivell Collection (Pictures), nla.cat-vn2098424

The exhibition featured significant numbers of original works completed on or soon after the voyages. Artists included the young Scottish Quaker Sydney Parkinson, the Swedish/Finnish naturalist Herman Diedrich Spöring and the Polynesian high priest Tupaia from the Endeavour voyage (1768–1771), the classically-trained William Hodges from the second voyage (1772–1775), and the prolific John Webber and assistant surgeon William Ellis from the third voyage (1776–1780). Many works of art in the exhibition were from the Library’s own collections, with numerous extraordinary loans from Australian and international lenders.

On the first voyage, the artists were part of the entourage of the young naturalist Joseph Banks. On the second and third voyages, they were appointed by the Admiralty. Lessons had been learned. Cook saw how well images could complement his reporting of the voyages. And over succeeding voyages, he came to direct and coordinate the artists’ work more closely.

We discussed many of these works, from all three voyages, with the First Nations communities we consulted during the exhibition’s development. Through them, we learned much. They could read the works in ways we could not. Though mediated through the artist, the works contained information that has cultural relevance and meaning today. Some of their comments are online at https://www.nla.gov.au/cook-and-the-pacific/first-nations-voices.

First voyage

Of course, the main aim of the Endeavour voyage was to observe the Transit of Venus at Tahiti on 3 June 1769. Then, following his ‘secret instructions’, Cook and his men sailed southward to search for the vast southern continent, an idea that had perplexed Europeans for centuries. As part of this, Cook circumnavigated New Zealand, and completed the map of Aotearoa New Zealand that Abel Tasman had started in the 1640s. To return home, Cook then decided to sail up what he thought to be the east coast of the land he knew from Dutch maps as New Holland (Australia). For obvious reasons, we focused on the Endeavour’s time in Australia in the exhibition.

Standouts dating from the Endeavour voyage in Cook and the Pacific included the sketchbook of Sydney Parkinson, on loan from the British Library. It was open to the pencil drawing of two Aboriginal men of Botany Bay.

Tupaia (c. 1724–1770), Australian Aboriginal People in Bark Canoes April 1770, pencil and watercolour, British Library, London, Add MS 15508, f.10, © British Library Board

Tupaia’s watercolour, also from the British Library, shows people fishing in canoes at Botany Bay in 1770. The opportunity to display this work was particularly exciting for us, being an image of First Nations people by a First Nations person. In his journal for 28 April 1770, Banks wrote about a scene that could have inspired this work:

By noon we were within the mouth of the inlet which appeard to be very good. Under the South head of it were four small canoes; in each of these was one man who held in his hand a long pole with which he struck fish, venturing with his little imbarkation almost into the surf. These people seemd to be totally engag’d in what they were about: the ship passd within a quarter of a mile of them and yet they scarce lifted their eyes from their employment; I was almost inclind to think that attentive to their business and deafned by the noise of the surf they neither saw nor heard her go past them.

Herman Spöring’s drawing of a stingray from Botany Bay was displayed near Sydney Parkinson’s sketch of a green turtle from Endeavour River, both drawings from the collections of London’s Natural History Museum. Sydney Parkinson’s preliminary drawing of a grevillea pteridifolia, collected at Cooktown, North Queensland, rounded out the works of art done on the Endeavour voyage. In a letter to his friend Dr John Fothergill, Joseph Banks wrote that Parkinson ‘with unbounded industry made for me a much larger number of drawings than I ever expected’. Parkinson completed 674 pencil drawings and 269 watercolours on that voyage. The sheer amount collected defeated even him, and he died in early 1771 in Batavia, before he could complete the watercolours of specimens collected in Australia.

Moses Griffith (1747–1819), Rainbow Lorikeet 1772, gouache on vellum, National Library of Australia, Pictures Collection, nla.cat–vn6155314

A poignant depiction of an Australian parrot, a rainbow lorikeet, ended the section. The bird is believed to have belonged to Tupaia. It returned alive to England with the Endeavour, and later became the property of Marmaduke Tunstall, a collector and friend of the naturalist Thomas Pennant. The artist Moses Griffith worked for Pennant, whose manuscript notebook was also on display in Cook and the Pacific. Pennant called Griffith an ‘untaught genius, drawn from the most remote and obscure parts of North Wales’. The work is considered the earliest painting, in colour, of an Australian bird.

Stay tuned for part 2.

Susannah Helman was co-curator and project manager of Cook and the Pacific.