They save lives and support people before and after disasters strike. They work to alleviate suffering during wars and conflict and promote the laws of war. And they work to assist our most vulnerable community members—no matter their circumstances. They are, the Australian Red Cross. The Australian Red Cross would not be what it is today without the tireless efforts of the men and women throughout history, who have provided their time, their skills and their friendly faces to help the community. This International Nurses Day, as healthcare professionals and volunteers across the nation work around the clock to keep our country safe, the National Library would like to thank them for their service by paying tribute the Australian Red Cross.

You would be hard pressed to find a person who has not been touched by Red Cross, knowingly or not: through a blood transfusion, during an emergency or natural disaster, or through work with the organisation as a volunteer or staff member. Many Australians, from young members of the Junior Red Cross to refugees to Australia searching for loved ones through the Tracing Service, have a Red Cross story to tell. Much of the organisation’s history is illuminated through the collections of the National Library: in manuscripts, sheet music and poems, posters and maps.

As is the case for many institutions and organisations in Australia, the roots of Australian Red Cross are bound up in our colonial relationship with Britain. It was formed in August 1914, just after the outbreak of the First World War, as a branch of the British Red Cross Society.

Australian Red Cross forms part of the International Red Cross and Red Crescent Movement, which is made up of three elements. The first of these is the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC), formed in Geneva, Switzerland, in 1863. Henry Dunant, one of the founders, was the author of A Memory of Solferino, a detailed eyewitness account of the horrors of the aftermath of the Battle of Solferino in Italy in 1859. In the book, he called for the establishment of a society of volunteers to assist the wounded in war.

The International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies (IFRC), created in 1919 and also based in Geneva, forms the second element of this worldwide humanitarian organisation. The third part of the movement is made up of, at last count, 189 national societies around the world, including Australian Red Cross.

Arthur Massey (music, 1861–1950), D.C. Cornwallis (lyrics), Angels of Mercy of the Red Cross Sign (cover), 1939, nla.cat-vn267063

The Red Cross idea is a simple one, going to the heart of what makes us human. To create an organisation of volunteers to assist, firstly, those on the battlefield and, later, civilians, through the Geneva Conventions, is one of the grand ideas of the nineteenth century. It is one that has survived and flourished into the twenty-first century. Its ambitious nature and global reach make the Red Cross all the more remarkable for, unfortunately, the need for it has not diminished with time. The emblem of the red cross on a white background (thought—although there is no direct evidence to prove this—to be the reversal of the Swiss flag) is enshrined in the Geneva Conventions.

Although there had been sporadic interest in the Red Cross movement in Australia prior to 1914, it took the alignment of two unrelated events—the arrival in Australia of our sixth Governor-General, Sir Ronald Munro Ferguson, and his wife, Lady Helen Munro Ferguson, in May 1914, and the outbreak of war three months later—for the Red Cross to be established.

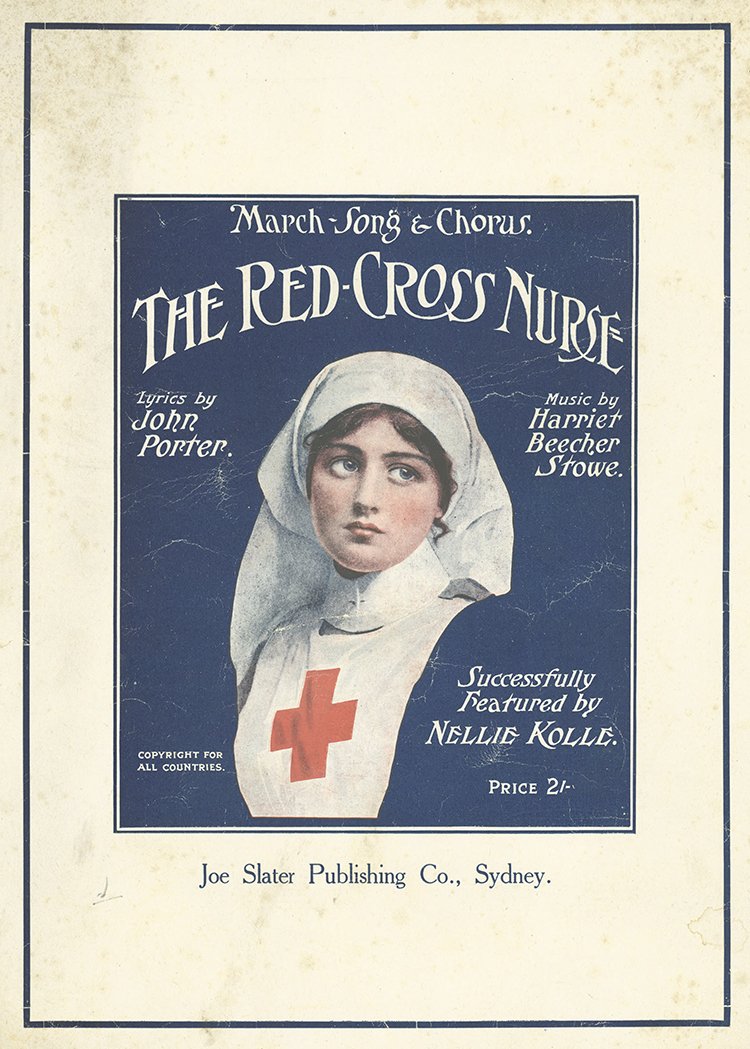

Harriet Beecher Stowe (music, 1811–1896), John Porter (lyrics), The Red-Cross Nurse: March—Song and Chorus (cover), 1914, nla.cat-vn1258829

Australian Red Cross was officially formed on 13 August 1914 when Lady Helen called together a group of distinguished individuals in the grand state ballroom of Government House in Melbourne. Lady Helen allowed her home to become the headquarters of the national body of Australian Red Cross, with divisions formed in all states, led by the wives of incumbent governors.

Largely due to the boundless energy and leadership acumen of the dynamic and forceful Lady Helen, Australian Red Cross burst onto the Australian stage. She viewed the member- based organisation as one primarily for women: part of their contribution to the war effort. Australian women agreed, and the idea was enthusiastically embraced. The Library holds rich sources relating to this early history of the Red Cross, including the papers of Ronald Munro Ferguson and of Lady Helen’s secretary, Miss Pharo.

Within months, Australian Red Cross was a household name and became the premier wartime charity. Focusing on assisting the sick and wounded in war—including soldiers, their dependents and Allied civilians overseas— Australian Red Cross played a vital role in providing medical equipment and supplies to military hospitals, both in Australia and overseas. It also had an army of volunteers who knitted socks and balaclavas, sewed pyjamas, packed parcels, raised funds and donated countless hours of unpaid labour for the duration of the war. The role of the extensive Red Cross branch network and its members was, as the 1916 publication Red Cross Work in NSW stated, to ‘mother’ the wounded or sick soldier, ‘to send him a shirt and a pair of socks, a towel and muffler, a packet of cigarettes and a box of chocolates ... crutches and artificial legs’.

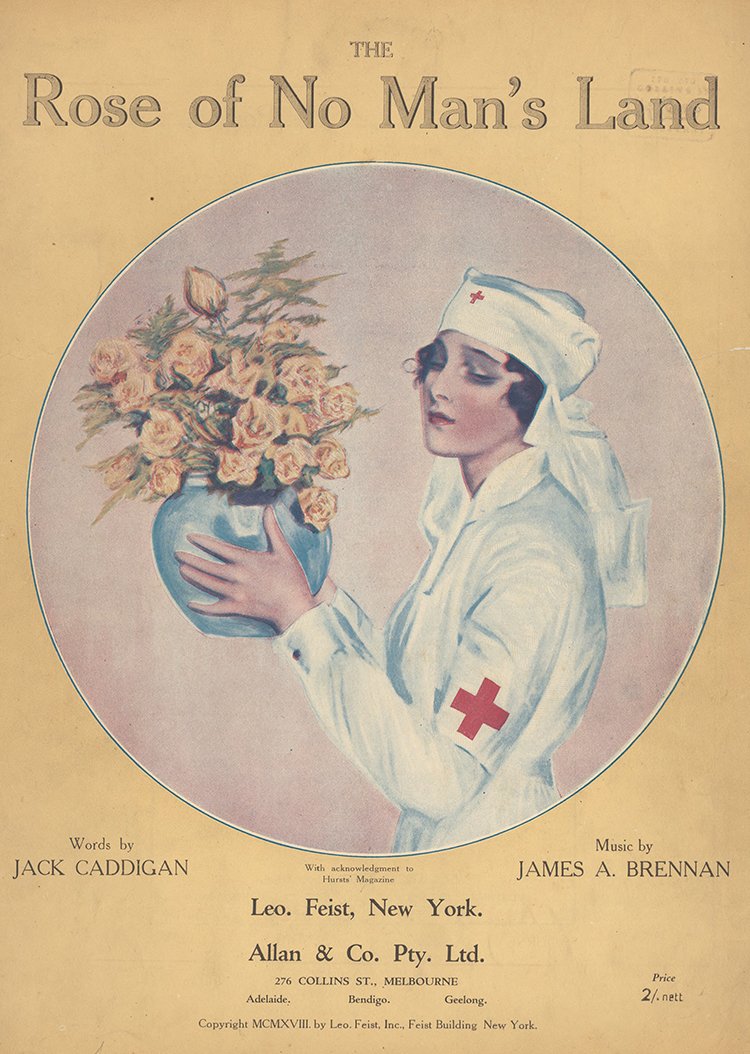

James Alexander Brennan (music, 1885 –1956), Jack Caddigan (lyrics), The Rose of No Man’s Land (cover), 1918, nla.cat-vn86545

Twenty-five years later, during the Second World War, the Red Cross’ special role in assisting service and ex-service personnel, prisoners of war and their dependents continued unabated. By this time, Australian Red Cross was the largest voluntary organisation in Australia, with a membership of over 450,000, of whom 95 per cent were women. Much of the organisation’s history revolves around women and women’s volunteer work. The extensive branch network that, at its height, had representation in most suburbs, small towns and regional centres around Australia, was the heart and soul of the organisation.

During this time, the Red Cross was again the beneficiary of an effective, highly competent and untiring leader: its president, Lady Zara Gowrie. The papers of her husband, Lord Gowrie, form part of the Library’s collection and detail aspects of her work. As part of the Lady Gowrie National Appeal, her Garden Fair, held at Government House, Canberra, on 20 April 1940, was the largest charity function that had ever been held in Australia.

The close connection with ex-service personnel continued to be a feature of Australian Red Cross until the 1970s, when the organisation moved away from this focus and towards assisting the disadvantaged and vulnerable within the general population.

The Red Cross Blood Transfusion Service was a significant legacy of the Second World War years. Started in Victoria in the late 1920s by Dr Lucy Bryce, a bacteriologist working at the Royal Melbourne Hospital, the service was expanded nationally during the war under the chairmanship of Dr John Newman-Morris, the eminent Melbourne surgeon. The Blood Transfusion Service became a major postwar public health program, sustained in large part by the volunteer labour of the Red Cross branch network. Today, it is for this service that most people in the community know Australian Red Cross.

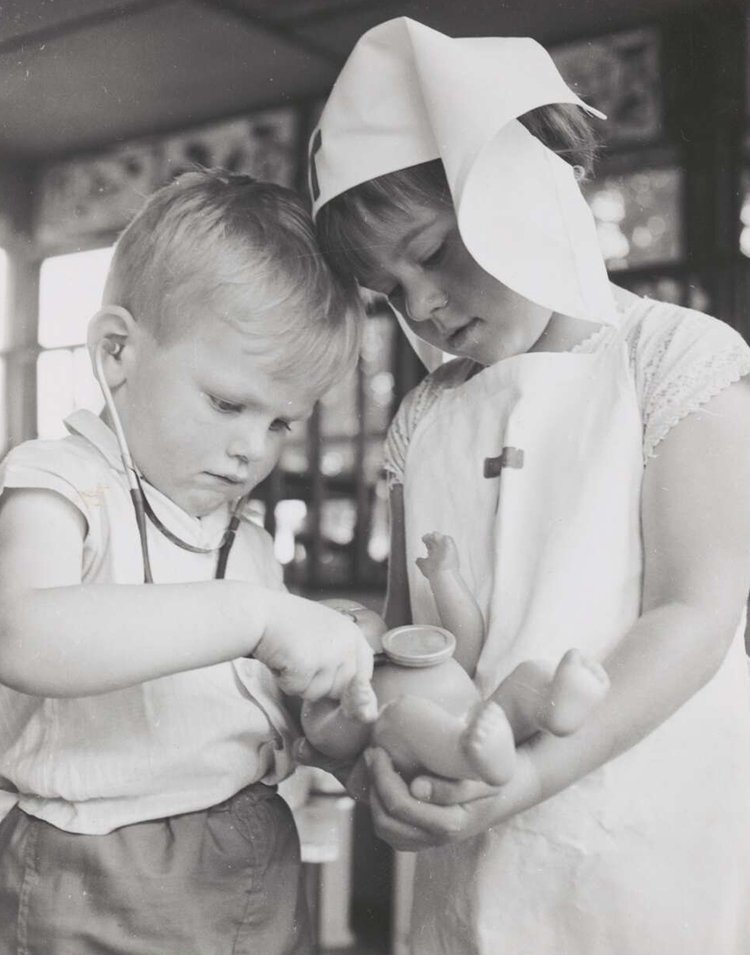

Cliff Bottomley, Australian News and Information Bureau, Boy and Girl Playing at Lady Gowrie Child Centre, Melbourne, December, 1963, nla.cat-vn6186394

Another area of ongoing Red Cross work, with origins in the First World War, is Tracing Services. The establishment of Wounded and Missing bureaux to help loved ones find information on their soldier relatives became a vital aspect of the Red Cross. During the Second World War, the service was extended to other wartime victims, including dispersed families and internees. The postwar immigration program brought to Australia thousands of people who had lost all contact with their families. The Tracing Bureau developed into a peacetime service largely assisting relatives and friends inquiring about displaced persons in Australia or overseas. For many, the Red Cross tracing network was their only hope of finding out the fate of family members. The highly regarded Tracing Program, now called Restoring Family Links, continues to provide assistance in disasters and national emergencies, as well as assisting newly arrived migrants and refugees to find missing family members.

The period after the Second World War saw reconstruction and regeneration that focused on social welfare, national emergencies, natural disasters such as floods and bushfires, and the development of a world-class blood transfusion service. An area of increasing importance to Australian Red Cross, developed from the 1970s onwards, has been International Humanitarian Law, otherwise known as the laws of war or laws of armed conflict. One of the champions of IHL, and a key personality within Red Cross, was Noreen Minogue. Her association with Australian Red Cross began when she was a volunteer during the Second World War. She later became a paid member of staff, and went on to be Deputy Secretary-General for 23 years.

Australian Red Cross continues to focus on disaster management. An integral part of government disaster plans for decades, Red Cross was involved in many of Australia’s most devastating natural disasters, including Cyclone Tracy, which hit Darwin on Christmas Eve in 1974. More recently, Australian Red Cross’ work during the catastrophic 2009 Victorian bushfires reminds us of the reach of its humanitarian role. Overseas, too, Australian Red Cross regularly contributes to international emergencies and incidents, such as the Asian Tsunami of 2005 and Typhoon Haiyan in the Philippines in 2013.

Australians are highly regarded within the Red Cross movement. They work with other members both through fundraising appeals and as delegates seconded to the ICRC, IFRC or National Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies and deployed in areas of global conflict. Delegates include nurses, midwives, surgeons, water engineers, logisticians and those with general health expertise.

As Australian Red Cross repositions itself within the non-government sector in the twenty-first century, its main focus is on Indigenous communities and other marginalised and vulnerable citizens, as well as the provision of international aid and emergency services.

With its mandate to be an auxiliary to the humanitarian services of the public authorities, Australian Red Cross is unique. It is part of the largest and oldest humanitarian organisation in the world, which recently celebrated 150 years. However, what continues to make Australian Red Cross what it is are the people. ‘People helping people’ is the motto for the organisation’s centenary year. That means it’s about being a member of the Red Cross family: a family of humanitarians, either in local communities or in remote parts of the world. It’s about people with vision, commitment and passion moving Australian Red Cross into its next 100 years.

Melanie Oppenheimer is Professor of History at Flinders University. She is the Australian Red Cross Centenary Historian, an Australian Red Cross Ambassador, and author of The Power of Humanity: 100 Years of Australian Red Cross.

This article was originally published in the June 2014 edition of The National Library of Australia magazine.