For centuries, explorers had been funded by their governments and by private investors to set out into unknown parts of the world. Many of these adventures were driven by the potential for profit and resources. Some sought to secure new strategic locations for trade routes and defence. Others aimed to spread religious influence. During the Enlightenment, more and more voyages into the ‘New World’ were driven by scientific forces. These voyages were not only looking to discover new lands, but to learn about them.

Travel by sea became safer and more efficient as the 18th century progressed, thanks to technological and scientific advancements in navigation and cartography, and a better understanding of the prevention and treatment of diseases like scurvy. This allowed ships to sail further, faster and with reduced morbidity and mortality of its crew.

Sept 7, 1778

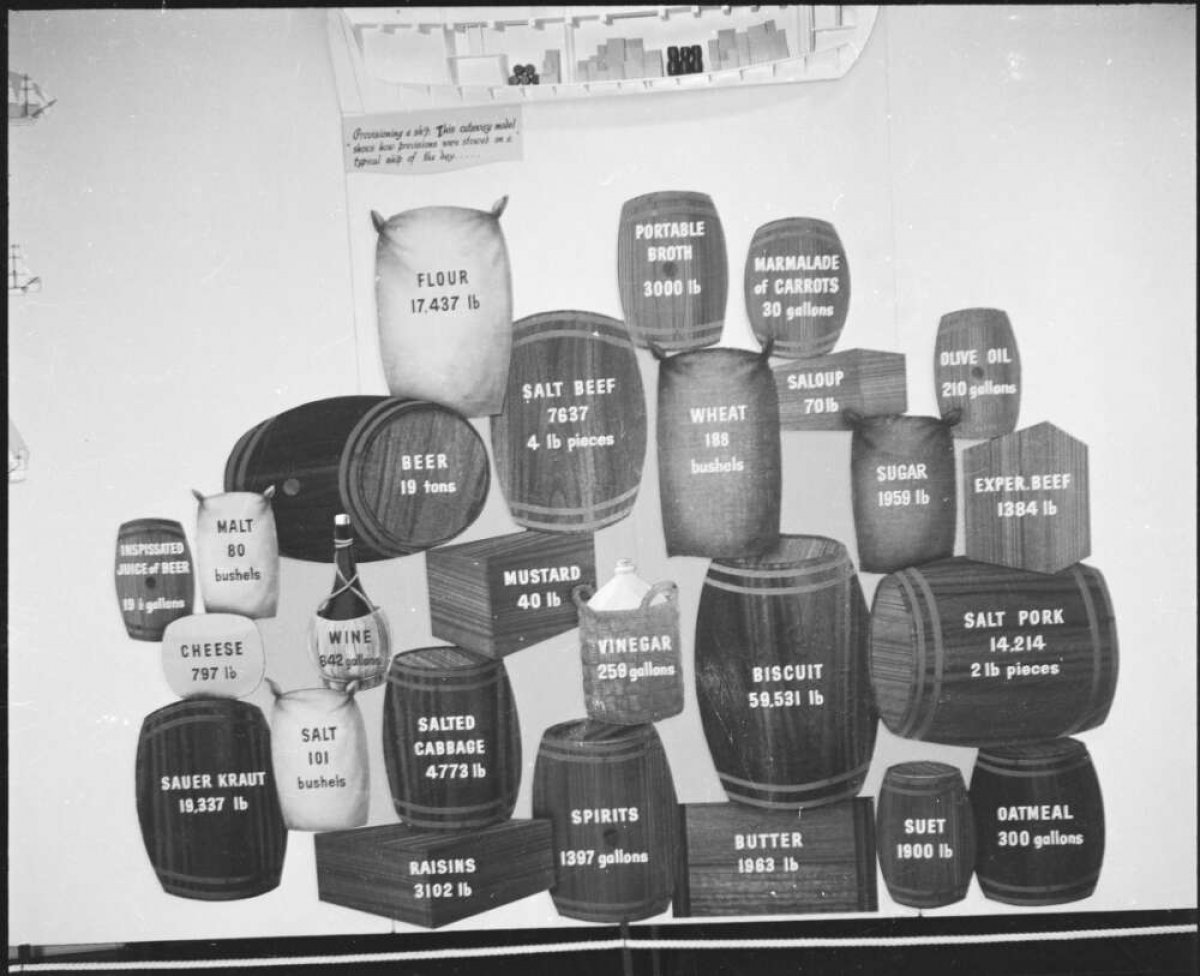

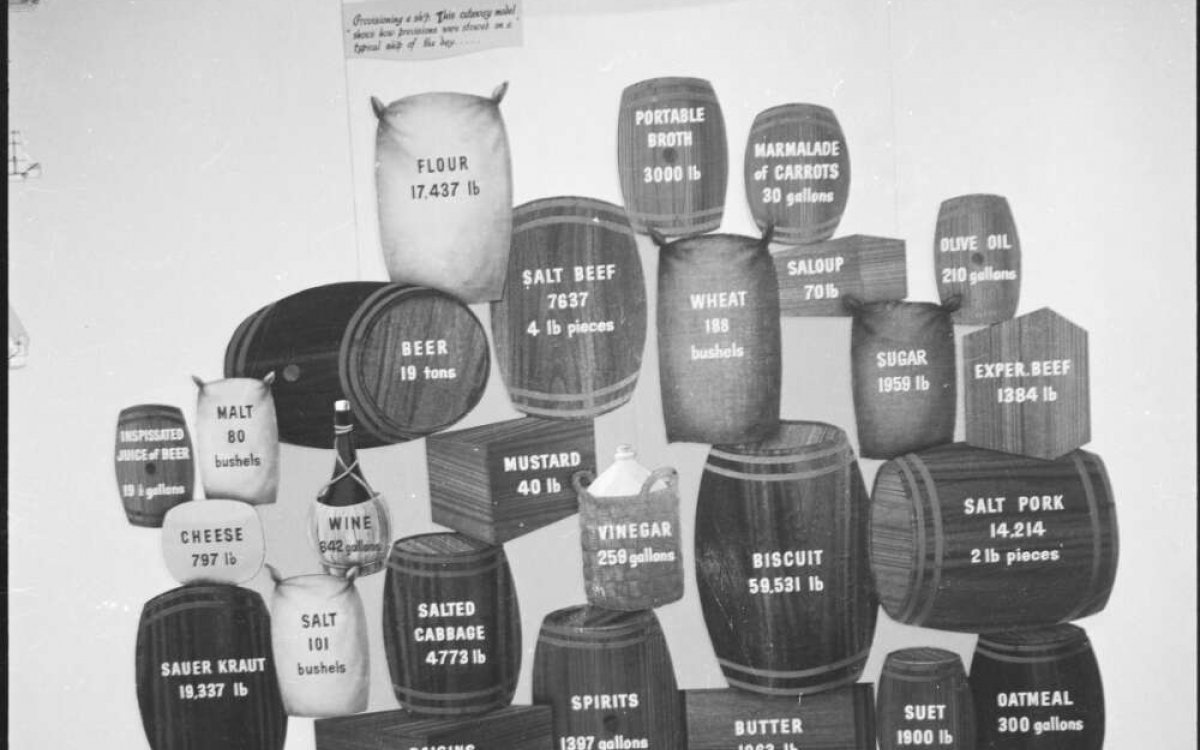

Every innovation whatever, tho ever so much to their advantage, is sure to meet the highest disapprobation from Seamen: Portable Soup and SourKrout were at first condemned by them as stuff not fit for human beings to eat. Few men have introduced into their ships more novelties in the way of victuals and drink than I have done. It has, however, in a great measure been owing to such little innovations that I have always kept my people generally speaking free from that dreadful distemper of Scurvy. (Cook's Journal: third voyage)

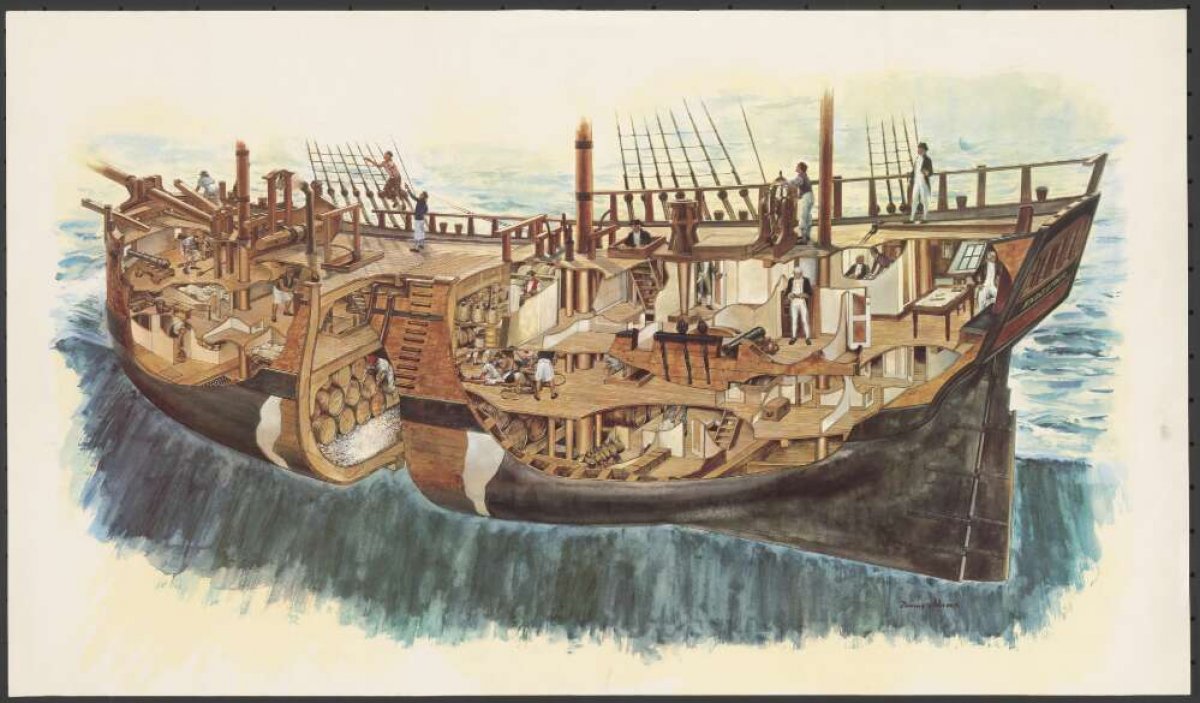

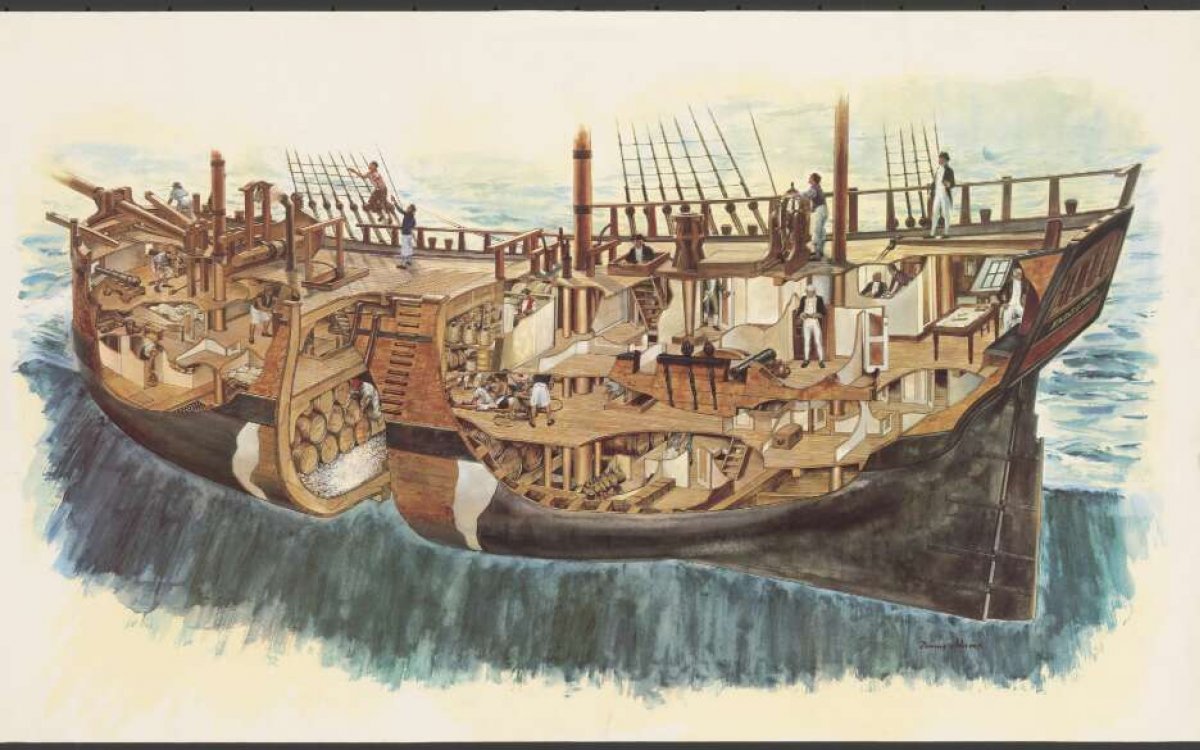

Ingleton, Geoffrey C. (Geoffrey Chapman) 1908-1998. (1937). H.M. Bark Endeavour [picture] / Geoffrey C. Ingleton. http://nla.gov.au/nla.obj-135348965

Adams, Dennis, 1914-2001. (1970). [Endeavour, below decks] [picture] / Dennis Adams. http://nla.gov.au/nla.obj-136065213

Terry, Michael, 1899-1981. (1969). Exhibition display showing the quantity and type of supplies onboard the Endeavour, Gisborne, New Zealand, 1969 / Michael Terry. http://nla.gov.au/nla.obj-241592478

The major European powers were engaged in a simmering academic contest to be the first to explore and chart the unknown places of the world. Between 1765 and 1795, the British, French, Russian and Spanish governments dispatched over 20 scientific voyages between them.

Some European Voyages of Discovery 1765–1795*

- 1764–66 : HMS Dolphin

- 1766–68 : HMS Dolphin and HMS Swallow

- 1766 : HMS Niger

- 1766–69 : La Boudeuse and L'Étoile

- 1768–71 : HMS Endeavour

- 1771–72 : Isle de France and Le Nécessaire

- 1772 : Sir Lawrence

- 1772–75 : HMS Resolution and HMS Adventure

- 1771–72 : La Fortune and Le Gros-Ventre

- 1773–74 : Le Roland and L'Oiseau

- 1773–74: HMS Racehorse and HMS Carcass

- 1776–80: HMS Resolution and HMS Discovery

- 1785–88: La Boussole and L'Astrolabe

- 1785–88 HMS King George

- 1785–94: Slava Rossii

- 1790–91: La Solide

- 1789–94: Descubierta and Atrevida

- 1791–94: La Recherche and L'Espérance

- 1791–93: HMS Providence

- 1791–95: HMS Discovery and HMS Chatham

*Voyages in bold denote Cook's voyages

Some European Voyages of Discovery 1765–1795*

- 1764–66 : HMS Dolphin

- 1766–68 : HMS Dolphin and HMS Swallow

- 1766 : HMS Niger

- 1766–69 : La Boudeuse and L'Étoile

- 1768–71 : HMS Endeavour

- 1771–72 : Isle de France and Le Nécessaire

- 1772 : Sir Lawrence

- 1772–75 : HMS Resolution and HMS Adventure

- 1771–72 : La Fortune and Le Gros-Ventre

- 1773–74 : Le Roland and L'Oiseau

- 1773–74: HMS Racehorse and HMS Carcass

- 1776–80: HMS Resolution and HMS Discovery

- 1785–88: La Boussole and L'Astrolabe

- 1785–88 HMS King George

- 1785–94: Slava Rossii

- 1790–91: La Solide

- 1789–94: Descubierta and Atrevida

- 1791–94: La Recherche and L'Espérance

- 1791–93: HMS Providence

- 1791–95: HMS Discovery and HMS Chatham

*Voyages in bold denote Cook's voyages

To prevent them being intercepted by international rivals, on returning to England in 1771 Captain Cook was urged to:

send to our Secretary, for our information, accounts of your Proceedings, and Copys of the Surveys and drawings you shall have made. And upon your Arrival in England you are immediately to repair to this Office in order to lay before us a full account of your Proceedings in the whole Course of your Voyage, taking care before you leave the Vessel to demand from the Officers and Petty Officers the Log Books and Journals they may have Kept, and to seal them up for our inspection, and enjoyning them, and the whole Crew, not to divulge where they have been until they shall have Permission so to do.

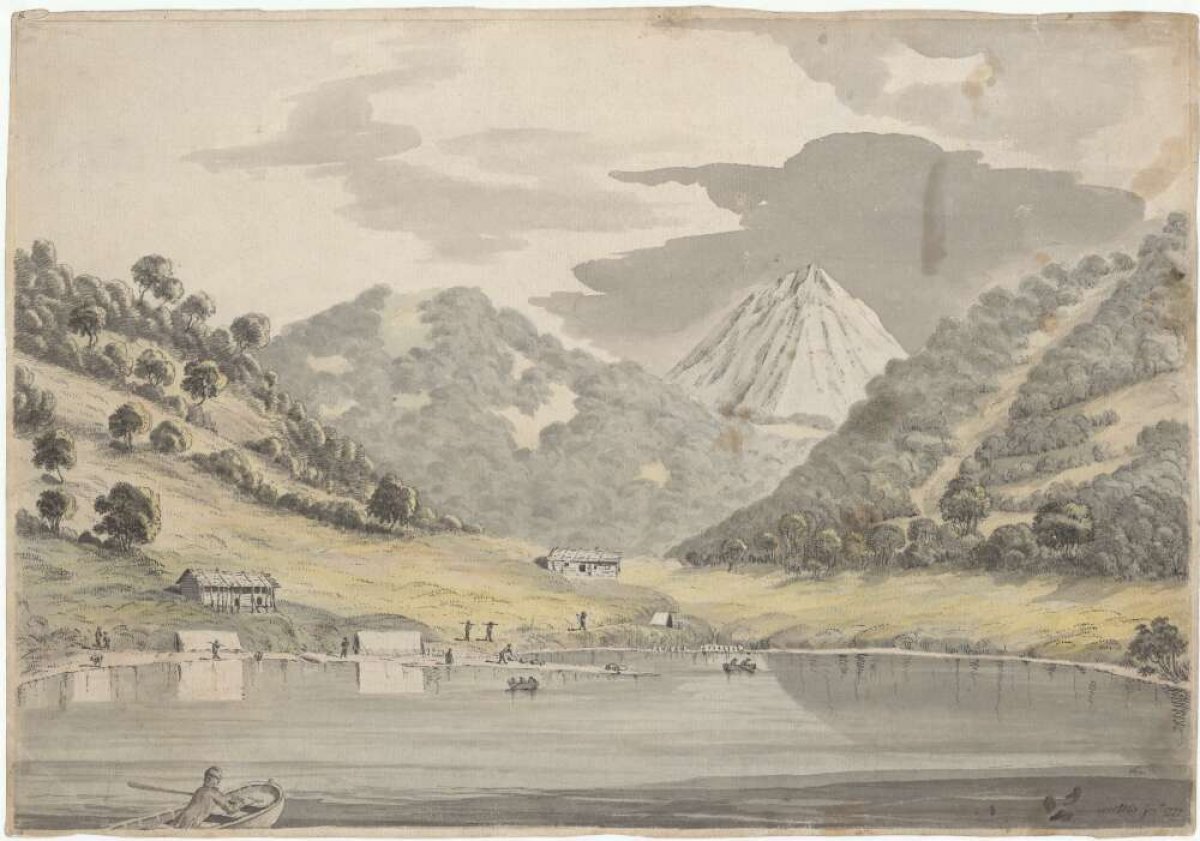

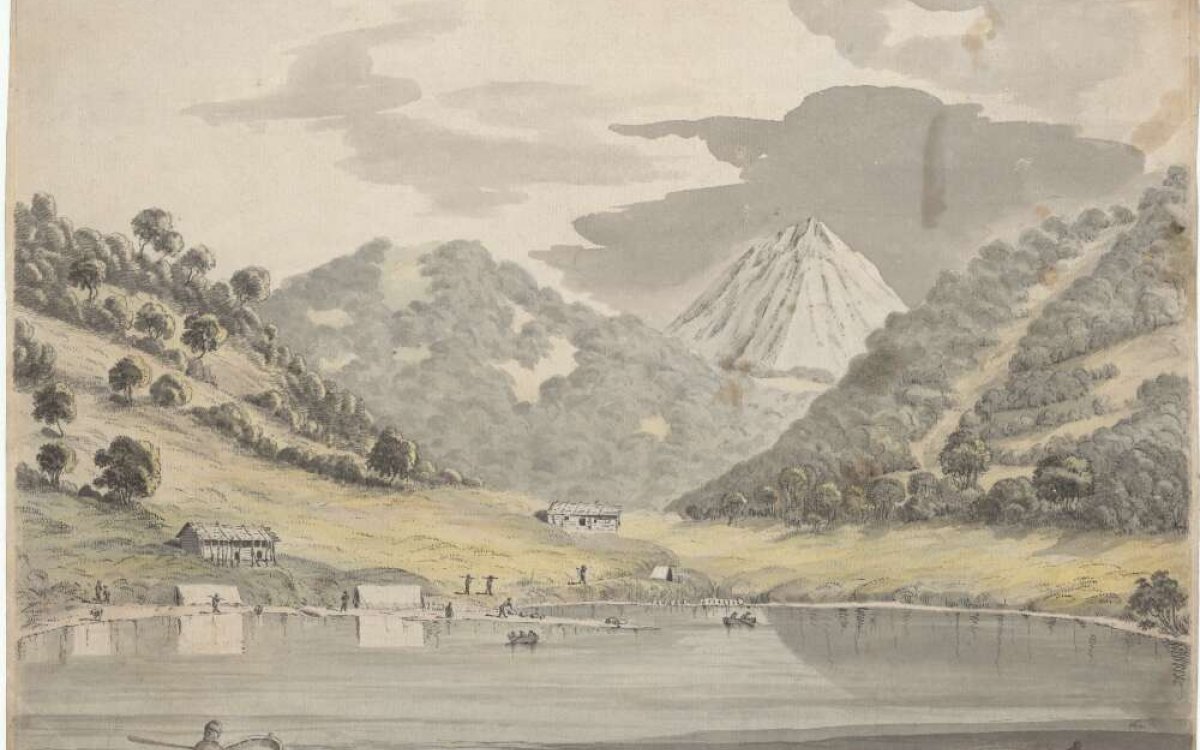

Ellis, William Wade, 1751-1785. (1779). [View in Avacha Bay, Kamchatka] [picture] / W.W. Ellis fect. http://nla.gov.au/nla.obj-134491602

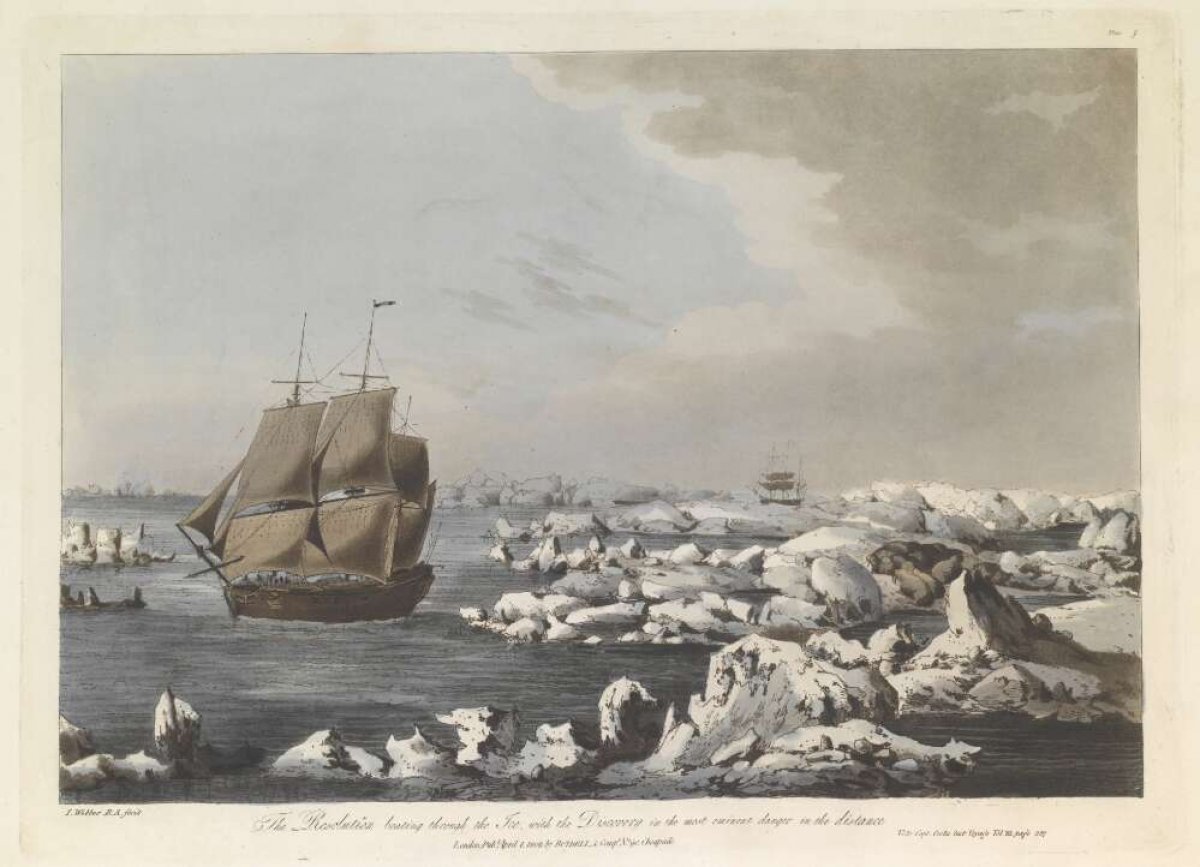

Webber, John, 1752-1793. Views in the South Seas. (1809). The Resolution beating through the ice, with the Discovery in the most eminent [sic] danger in the distance [picture] / J. Webber fecit. http://nla.gov.au/nla.obj-135773713

Many of the great scientific voyages of the Enlightenment era included scientists, botanists, doctors and other experts in a range of fields. They made meteorological, hydrological and geographical observations, and many brought back to Europe specimens of newly discovered flora and fauna. This stimulated great advances in a number of scientific disciplines, including botany, zoology, ichthyology, conchology, taxonomy, medicine, geography, geology, mineralogy, hydrology, oceanography, physics and meteorology.