This resource has been generously supported by Optus. Through the Digital Thumbprint program and Kids Helpline @ School, Optus supports digital knowledge and the positive use of technology.

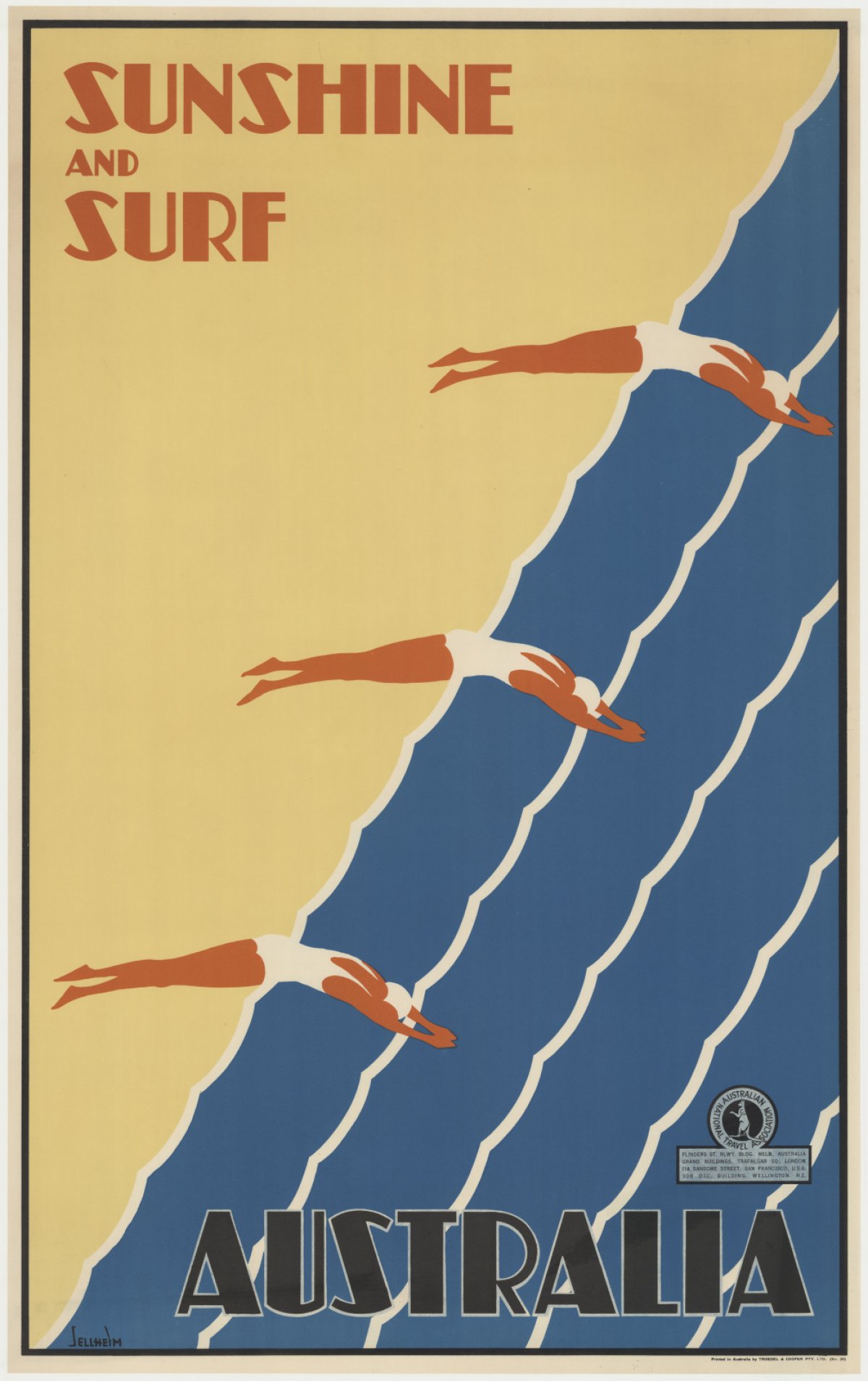

Sellheim, Gert, 1901-1970 & Australian National Travel Association. (1936). Sunshine and surf : Australia / Sellheim. https://nla.gov.au/nla.cat-vn6385925

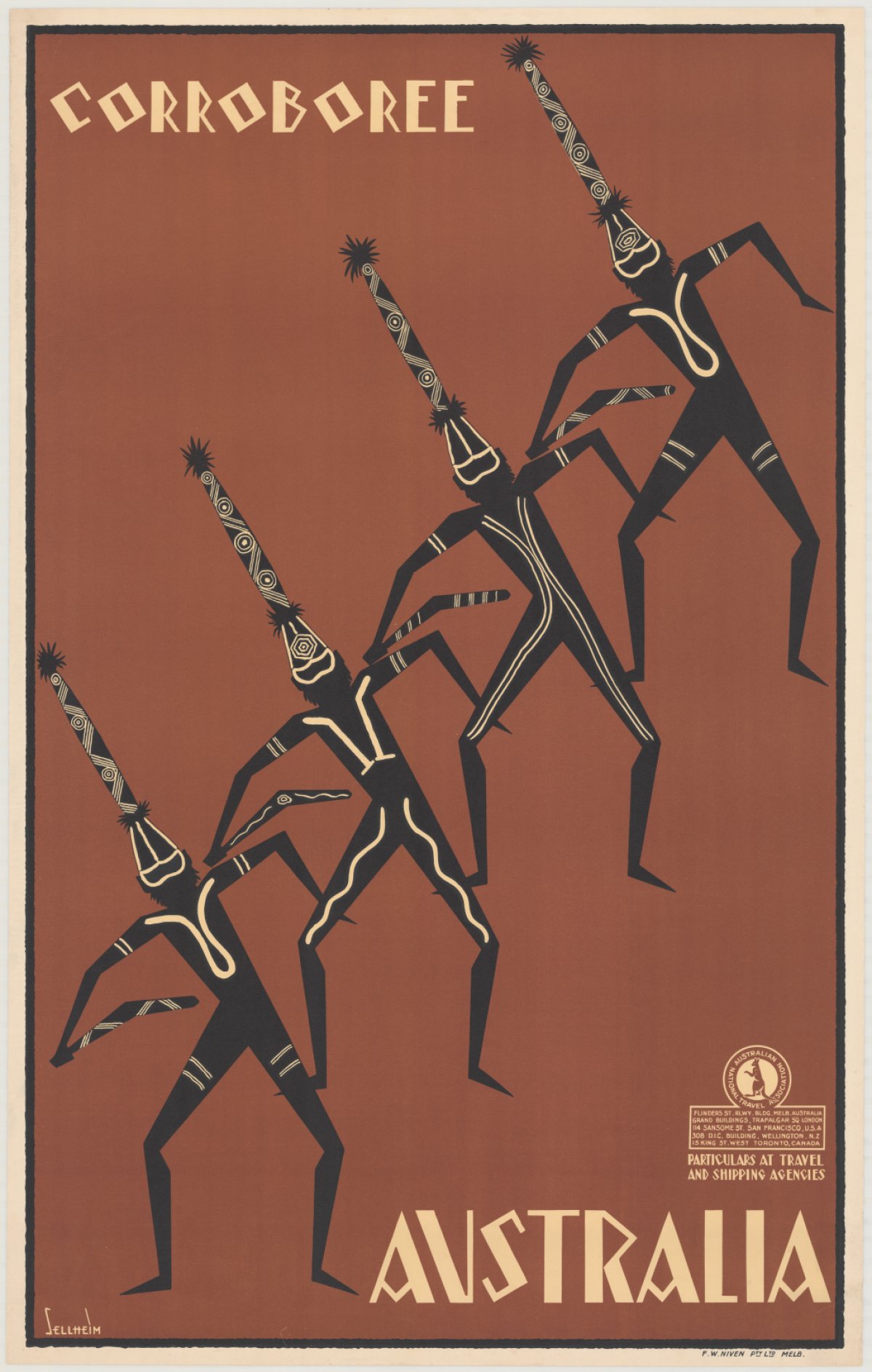

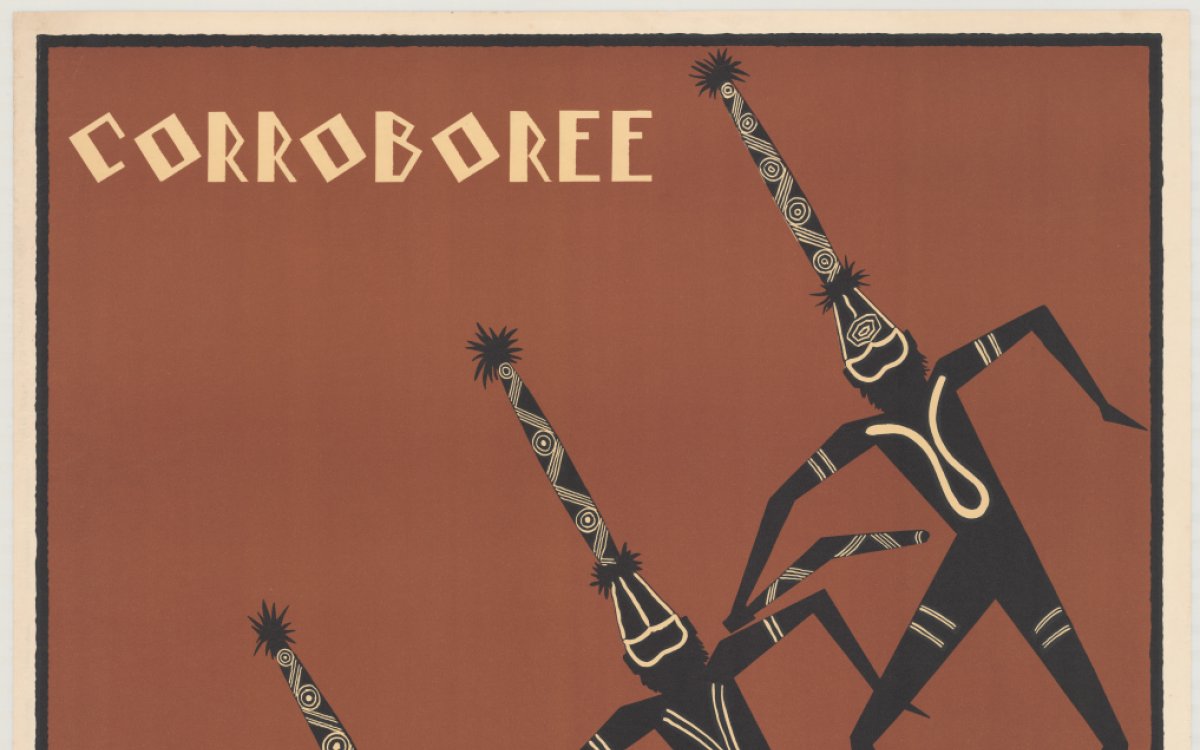

Sellheim, Gert, 1901-1970 & Australian National Travel Association. (1931). Corroboree, Australia [picture] / Sellheim. https://nla.gov.au/nla.cat-vn84186

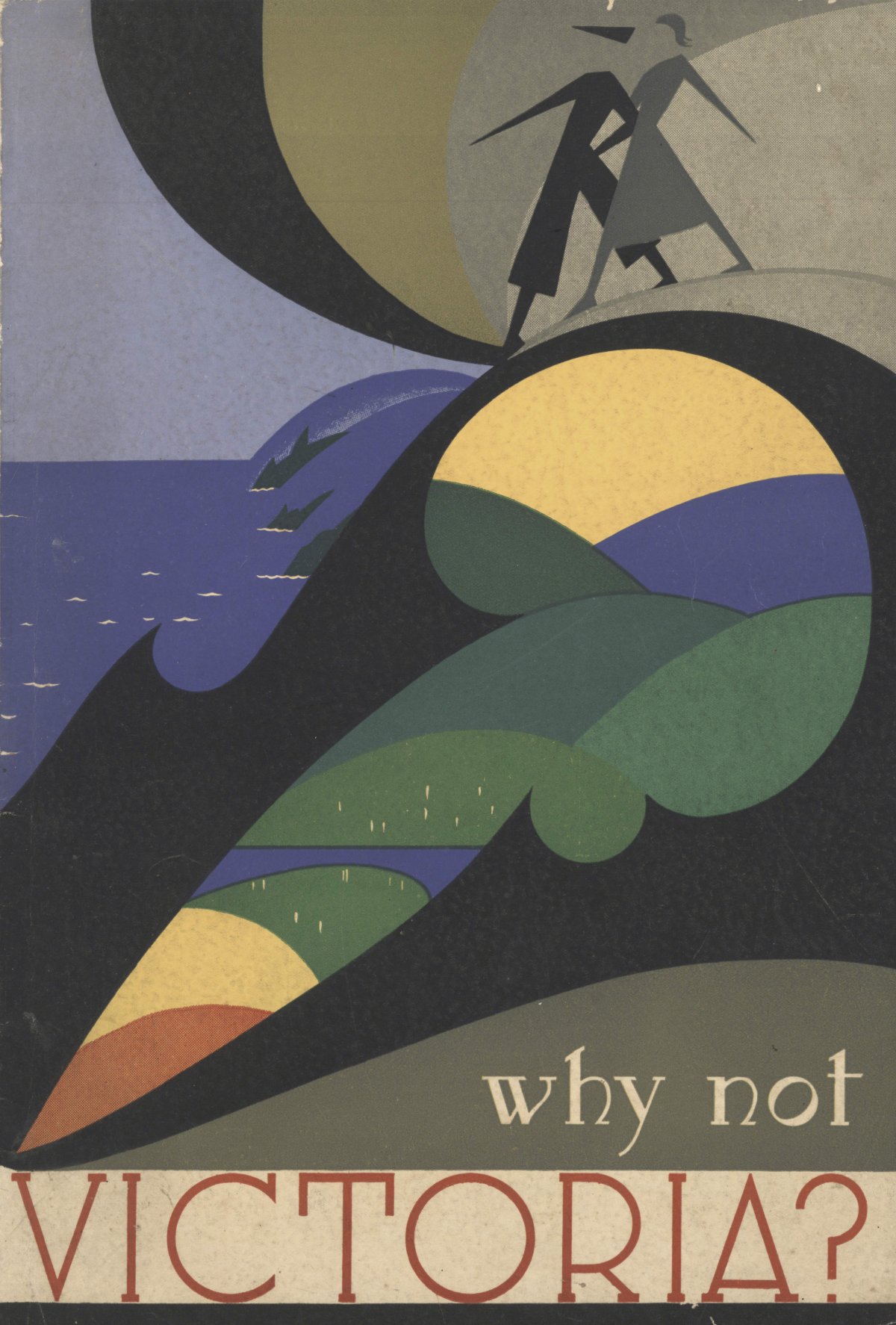

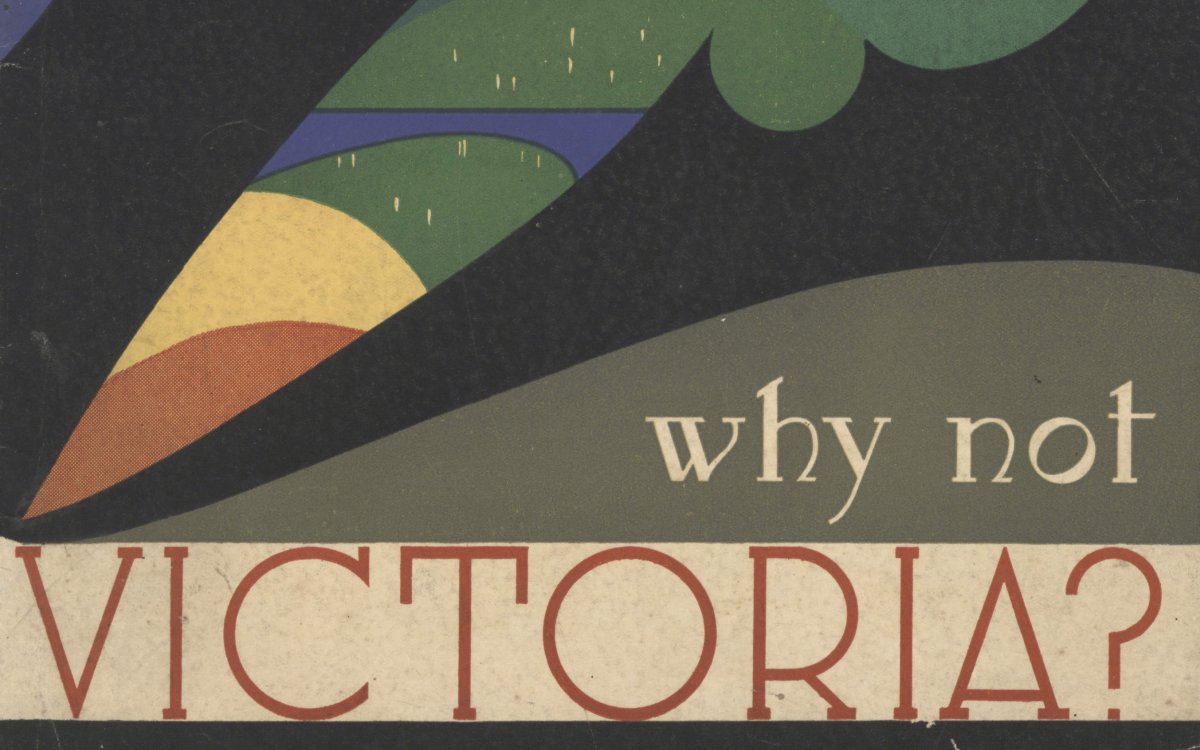

Ziegler, Oswald L. (Oswald Leopold), 1900-1984 & Sellheim, Gert, 1901-1970 & Lyons, J. A. (Joseph Aloysius), 1879-1939. (1938). Why not Victoria? / created and produced by Oswald L. Ziegler ; cover and pictorial map designed by Gert Sellheim. Melbourne, Vic. : Melbourne : Oswald L. Ziegler, Premier Printing Co. http://nla.gov.au/nla.obj-186171624

The Australian National Travel Association

The Australian National Travel Association (ANTA)—Australia’s peak semi-government tourist body—operated from July 1929 with a mission ‘to place Australia on the world’s travel map and keep it there’. ANTA produced many iconic travel posters of the 1930s to the 1950s. It advertised extensively in different media, including magazines and films, within Australia and overseas. Estonian-born German Gert Sellheim, who migrated to Australia in 1926, was one of ANTA’s earliest and most original artists. Sellheim’s posters were not tokenistic. They portrayed a real rather than idealised vision of Australia. Other early artists for ANTA were Percy Trompf, James Northfield and Douglas Annand.

‘Why not Victoria?’

Sellheim continued to work in commercial art and collaborated many times with writer Oswald L. Ziegler. Sellheim designed the book and Ziegler wrote the text. This example, with plentiful photographs of Victoria’s holiday spots, has a foreword by the then Prime Minister Joseph Lyons, who makes the book’s purpose clear: ‘Glancing through these pages, one is forced to wonder why tourists should leave Australia before they have viewed the magnificent scenery of their own country’.

The Australian National Travel Association

The Australian National Travel Association (ANTA)—Australia’s peak semi-government tourist body—operated from July 1929 with a mission ‘to place Australia on the world’s travel map and keep it there’. ANTA produced many iconic travel posters of the 1930s to the 1950s. It advertised extensively in different media, including magazines and films, within Australia and overseas. Estonian-born German Gert Sellheim, who migrated to Australia in 1926, was one of ANTA’s earliest and most original artists. Sellheim’s posters were not tokenistic. They portrayed a real rather than idealised vision of Australia. Other early artists for ANTA were Percy Trompf, James Northfield and Douglas Annand.

‘Why not Victoria?’

Sellheim continued to work in commercial art and collaborated many times with writer Oswald L. Ziegler. Sellheim designed the book and Ziegler wrote the text. This example, with plentiful photographs of Victoria’s holiday spots, has a foreword by the then Prime Minister Joseph Lyons, who makes the book’s purpose clear: ‘Glancing through these pages, one is forced to wonder why tourists should leave Australia before they have viewed the magnificent scenery of their own country’.

Poster artists working for The Australian National Travel Association (ANTA) had to decide which pictorial styles would best convey Australia’s attractions. At home, a ‘nationalist’ style, represented by the works of Arthur Streeton, Tom Roberts and Hans Heysen, was believed the best to symbolise Australia. But, because travel posters were intended for an international audience—at least, initially—some of the pictorial styles used for them would have been regarded as radically modern by people in Australia.

The appropriation of Aboriginal imagery became a characteristic of postwar modernism within Australian art and culture. To achieve a distinctly Australian look, inspiration for travel posters was drawn from the X-ray art style, from rock paintings and from Aboriginal material culture. Aboriginal motifs, such as the boomerang, were often tempered with non-Aboriginal motifs of Australia such as swimsuit-clad women or sheep.

Chromolithography

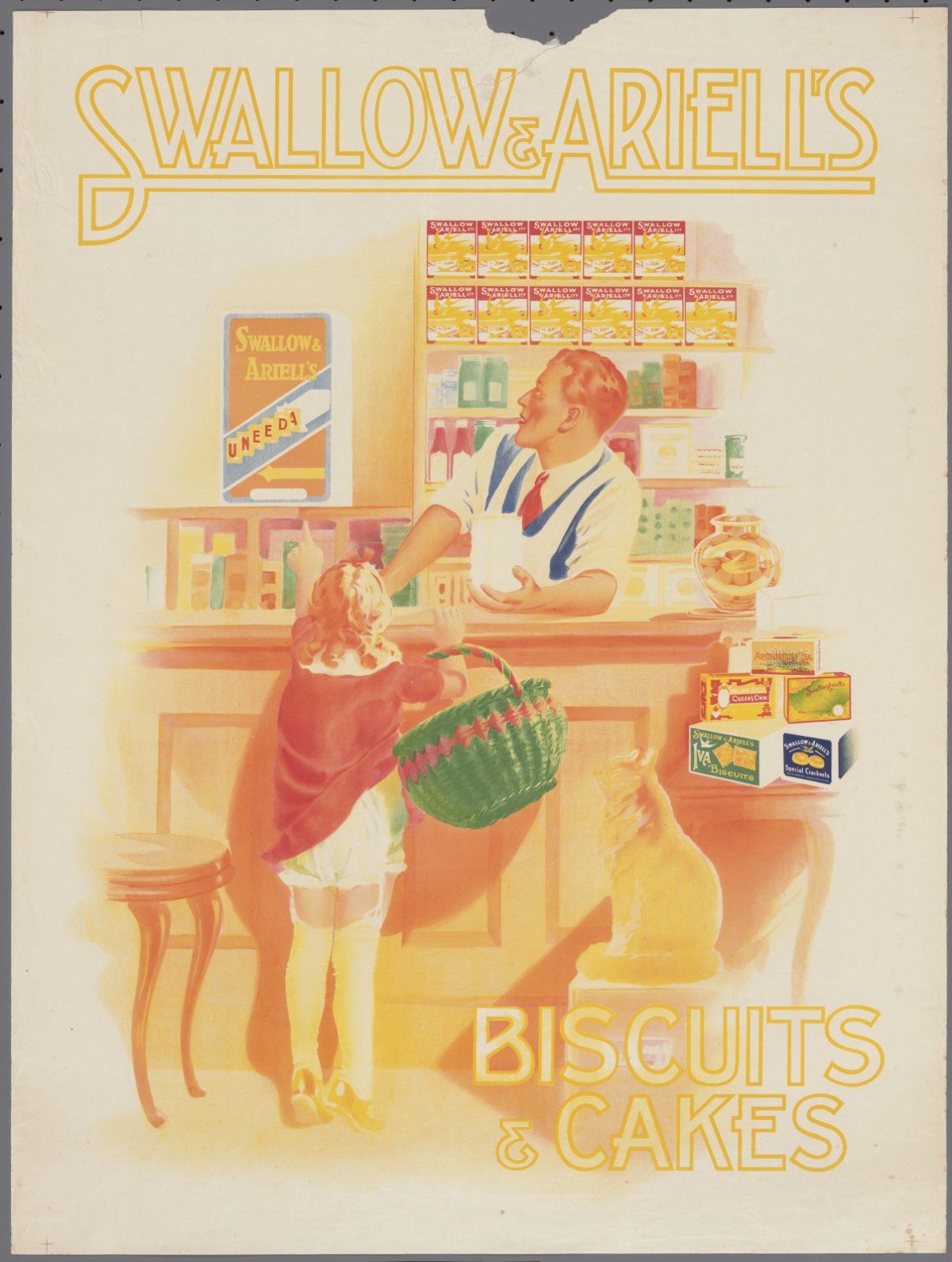

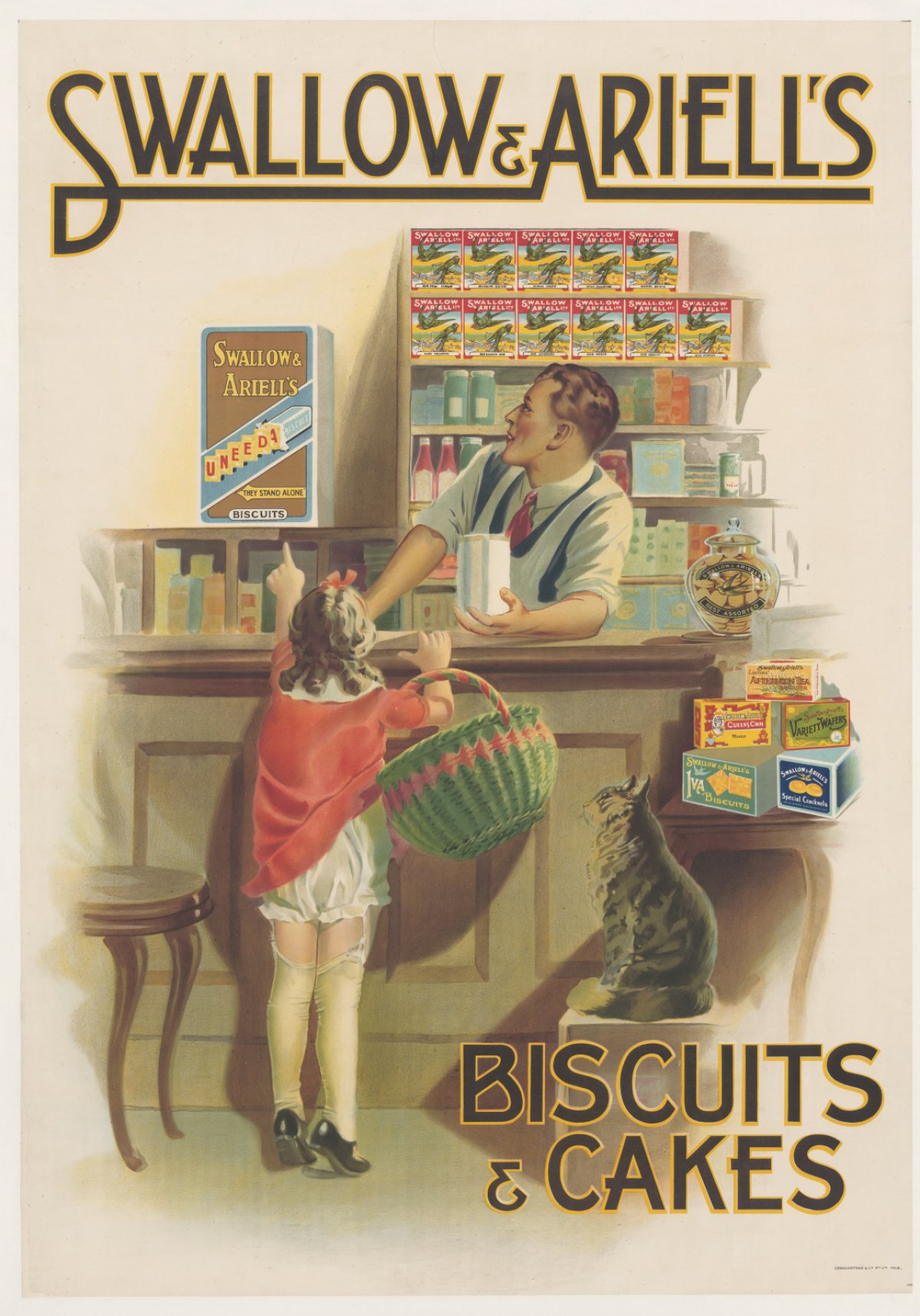

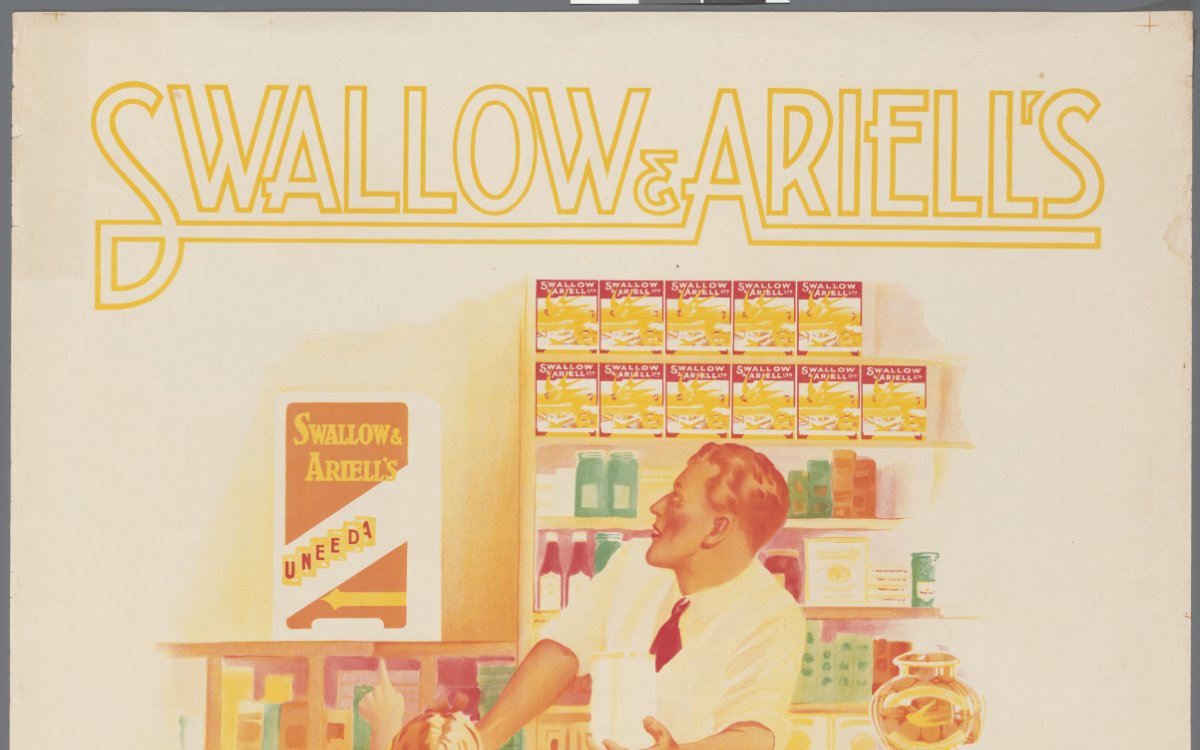

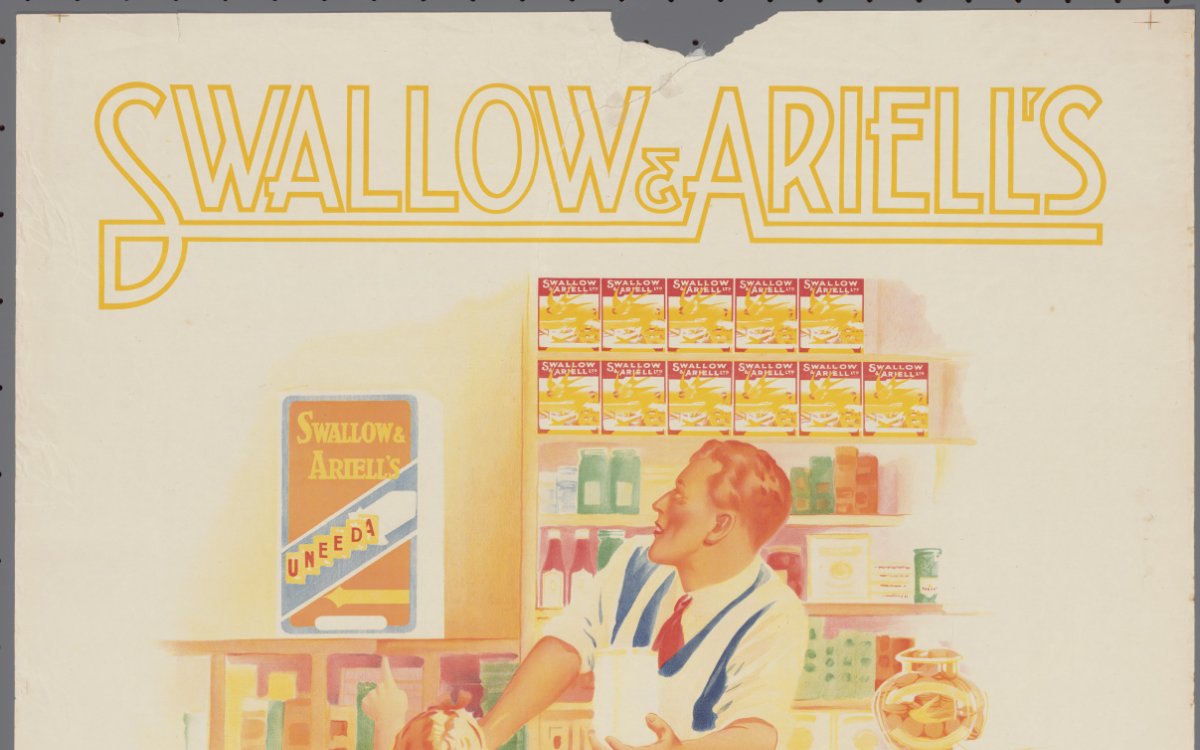

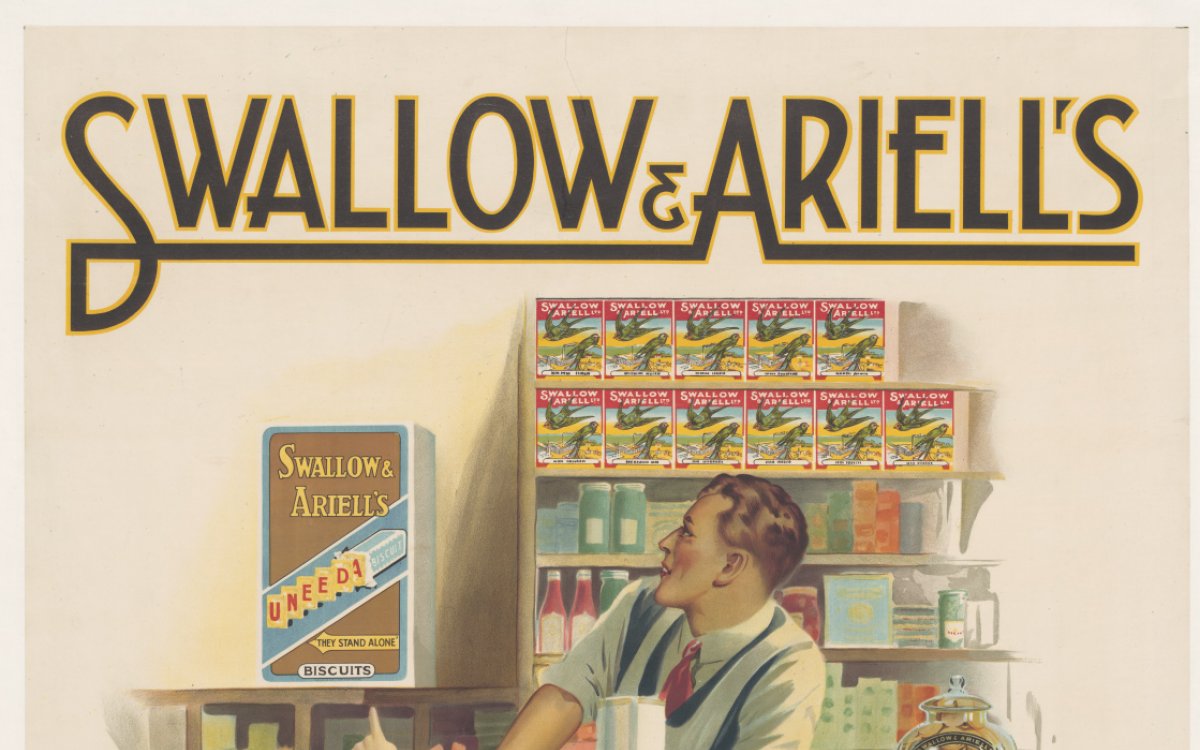

Northfield, James, 1887-1973 & Northfield Studios. [Three colour printer's proof of the Swallow and Ariell's biscuits and cakes advertisement] [picture] / James Northfield. https://nla.gov.au/nla.obj-136965119

Northfield, James, 1887-1973 & Northfield Studios. [Four colour printer's proof of the Swallow and Ariell's biscuits and cakes advertisement] [picture] / James Northfield. https://nla.gov.au/nla.obj-136965275

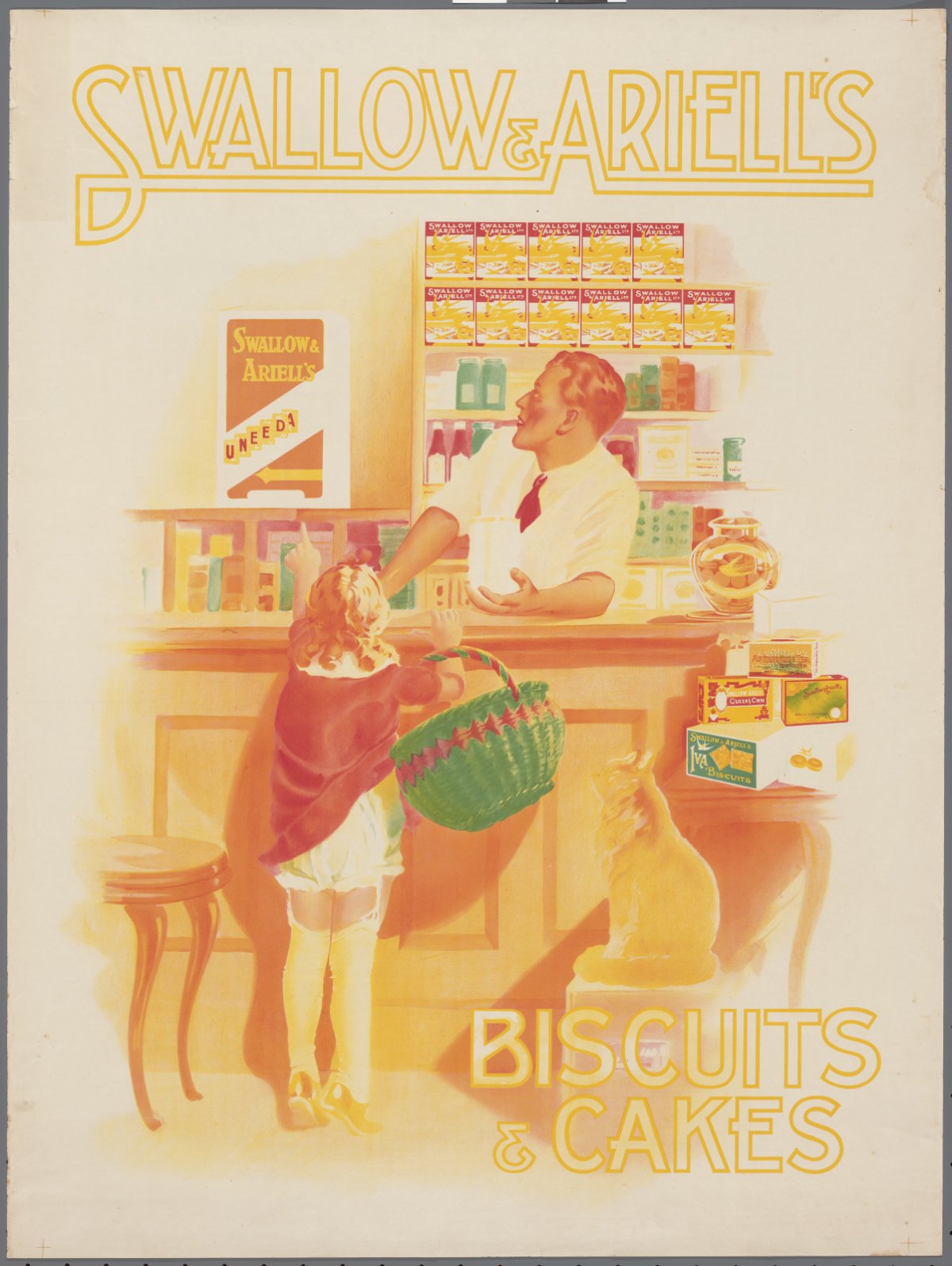

Swallow & Ariell Ltd & Northfield, James, 1887-1973. (1920). Swallow & Ariell's biscuits & cakes [picture]. https://nla.gov.au/nla.obj-136983201

Chromolithographs

With artwork attributed to renowned poster artist James Northfield, this poster, in three states, gives an idea of how a colour lithograph was created. Chromolothographs are produced by printing from smooth-surfaced limestone or zinc plates that have been chemically treated. Each colour is applied separately. Northfield had an extensive career in commercial art and taught at Melbourne’s Art Training Institute.

Swallow & Ariell was an enthusiastic advertiser throughout its long history. Founded in the 1850s, it was purchased by Arnotts’ in 1964. This poster, and the object of the little girls’ attention, features one of their most popular biscuits, the Uneeda.

More Swallow & Ariell's ads can be found in the Trove list below:

The Sell: Australian Advertising 1790s to 1990s – Swallow & Ariell

Chromolithographs

With artwork attributed to renowned poster artist James Northfield, this poster, in three states, gives an idea of how a colour lithograph was created. Chromolothographs are produced by printing from smooth-surfaced limestone or zinc plates that have been chemically treated. Each colour is applied separately. Northfield had an extensive career in commercial art and taught at Melbourne’s Art Training Institute.

Swallow & Ariell was an enthusiastic advertiser throughout its long history. Founded in the 1850s, it was purchased by Arnotts’ in 1964. This poster, and the object of the little girls’ attention, features one of their most popular biscuits, the Uneeda.

More Swallow & Ariell's ads can be found in the Trove list below:

The Sell: Australian Advertising 1790s to 1990s – Swallow & Ariell

Explore the process of lithography with students. You may wish to begin by watching the video below, developed for another National Library exhibition—Australian Sketchbook: Colonial Life and the Art of ST Gill, which looks at the basic process of lithography in the mid-nineteenth century.

Compare the techniques used by ST Gill with those used around 60 years later by James Northfield.

Have students research and explain the difference between a lithograph and a chromolithograph.

ST Gill didn’t make his prints for advertising purposes, but Northfield did. What are some elements of the art making process that change when the artist is developing advertising materials, rather than art for art’s sake?

Advertising agencies have Creative Directors and Art Departments. Have students consider the relationship between art and advertising. Organise a small informal debate in the classroom taking the topic ‘Can advertising be considered art?’ The teams should consider advertising campaigns as a whole, as well as the visual elements they contain.

This discussion might lead into an examination of ‘Commercial art’ and vocational options for students of the Visual Arts aside from a career as a fine artist.

Photography

Cazneaux, Harold, 1878-1953. (1932). Portrait of Patricia Minchin holding a cake, Chatswood, New South Wales, 1932 [picture] / Harold Cazneaux. http://nla.gov.au/nla.obj-140227282

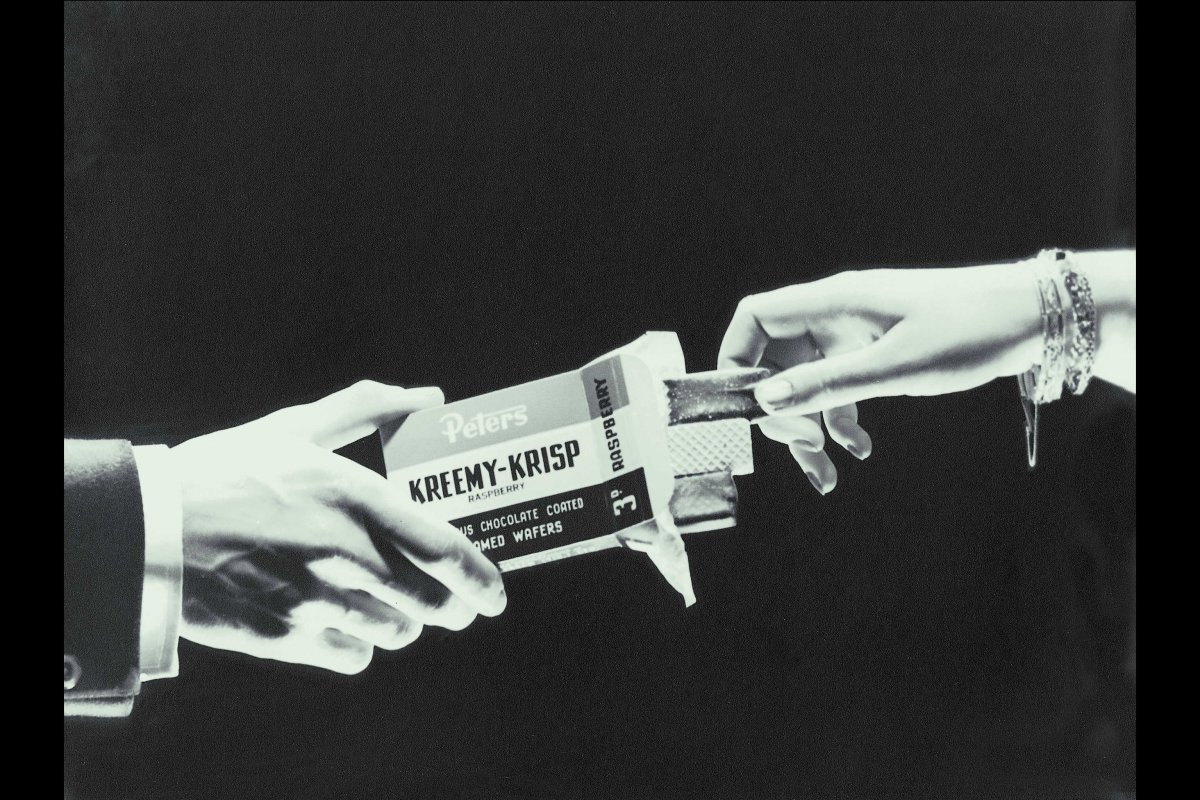

Sievers, Wolfgang, 1913-2007. (1939). Advertisement for Peter's Icecream 1940 [picture] / Wolfgang Sievers. http://nla.gov.au/nla.obj-143278035

Photographer Harold Cazneaux and model

Harold Cazneaux advertised in the upmarket magazine, The Home, in the early 1930s. He also took private portraits and shot advertising brochures for companies. The Library holds Cazneaux’s papers, allowing us to explore the process of commissioning of work. Patricia Minchin (1910–2002), modelled for Cazneaux on a number of jobs, including this image that was used in an advertisement for White Wings flour.

Wolfgang Sievers

Wolfgang Sievers arrived in Australia in 1938 with experience in commercial photography, particularly advertising. The Library holds several advertising photographs from his time in Berlin and also from soon after his arrival in Australia. Though declared an enemy alien, despite effectively being a refugee from Nazi Germany, he was able to work in advertising. This photograph was one he did for Peters. In his job book—a manuscript held by the Library—he describes it as ‘Kreemy Krisp with hands’ for Richards Advertising Agency.

Photographer Harold Cazneaux and model

Harold Cazneaux advertised in the upmarket magazine, The Home, in the early 1930s. He also took private portraits and shot advertising brochures for companies. The Library holds Cazneaux’s papers, allowing us to explore the process of commissioning of work. Patricia Minchin (1910–2002), modelled for Cazneaux on a number of jobs, including this image that was used in an advertisement for White Wings flour.

Wolfgang Sievers

Wolfgang Sievers arrived in Australia in 1938 with experience in commercial photography, particularly advertising. The Library holds several advertising photographs from his time in Berlin and also from soon after his arrival in Australia. Though declared an enemy alien, despite effectively being a refugee from Nazi Germany, he was able to work in advertising. This photograph was one he did for Peters. In his job book—a manuscript held by the Library—he describes it as ‘Kreemy Krisp with hands’ for Richards Advertising Agency.

Harold Cazneaux and Wolfgang Sievers are two of Australia’s most well-known photographers. Both worked for the advertising industry but presented two very different traditions in their work. Cazneaux’s practice was rooted in pictorialism, while the Bauhaus-trained Sievers was a modernist.

- What is pictorialism in photography?

- Define modernism as it relates to art, especially photography.

- Considering both Cazneaux’s and Sievers’ work, discuss the photographic techniques they might have used to achieve their desired effects. Use Trove to find examples from both photographers.

- Which elements of pictorialism and modernism lend themselves particularly well to advertising work?

- How do pictorialism and modernism differ?

Later in his career, Wolfgang Sievers struggled with the ethics of producing hyperreal, sanitised and glamourised portrayals of industry and businesses for commercial purposes. Although some industries impacted on the Australian environment in a negative way, Sievers’ images invariably excluded the true environmental impacts of such industries:

I am quite aware of the moral problems confronting a responsible photographer in industry … Should he use his skills to hide the terrible pollution and despoliation of our country—as I have? In creating beautiful images I have glamorised industries which have often been heedless of their sacred trust to use resources wisely and take care in the interest of future generations. In my defence, so far, I have found no valid answer to these problems.

(Barry York, oral history interview with Wolfgang Sievers, March 2000, ORAL TRC 4549)

- Use this quote as a stimulus for further discussion about commercial art. Discuss the concept of ‘selling out’ by artists who work in the commercial sphere. How do artists balance their ethics and integrity with the need to make a living from their work?