Coffin, Yves, 1924-2016. (1960). [Preah Khan, rows of stone posts lined towards gopura] [picture] / Yves Coffin. https://nla.gov.au/nla.obj-140374253

The Khmer Empire lasted almost 630 years. For all its splendour, there is very little primary source information relating to the day-to-day life of the people or the workings of government. Most of what modern scholars know of life at Angkor comes from the stone carvings found on temple walls. During the Khmer Empire, records were kept on paper made from leaf fibres, rice paper or vellum. The climate of Cambodia is tropical, with hot humid summers and only slightly less humid winters. Without proper preservation and storage, fibrous material such as wood, leaves and paper are susceptible to decay in these conditions. As such, the paper-based administrative records of the Angkor empire no longer exist. This leaves large gaps in our knowledge of what daily life was like in the empire.

What scholars do know about the day-to-day life of the Khmer people comes from foreign visitors to the kingdom. The most well known and comprehensive record of life in the Khmer Empire is that of Zhou Daguan. Zhou was part of a diplomatic mission sent to Cambodia by Temür Khan, the second emperor of the Yuan dynasty of China, in 1296. His account is believed to have been compiled sometime after his return to China, but before 1312. It was first transcribed from Chinese to French in approximately 1820. It was not translated into English until 1967.

It is worth noting that, even though it is the most comprehensive contemporary account of the Khmer Empire, scholars are constantly revising and reconsidering the account, given the age of the document. The language and dialects used by Zhou Daguan in the thirteenth century have changed and evolved since then and many translations have also been translated, not from the original Chinese but through various secondary translations. As each new translation is made, the clarity and accuracy of the account diminishes.

It is worth noting that, even though it is the most comprehensive contemporary account of the Khmer Empire, scholars are constantly revising and reconsidering the account, given the age of the document. The language and dialects used by Zhou Daguan in the thirteenth century have changed and evolved since then and many translations have also been translated, not from the original Chinese but through various secondary translations. As each new translation is made, the clarity and accuracy of the account diminishes.

Zhou Daguan left a detailed, yet brief, account of his time visiting Angkor. His account is arranged under 40 headings, each detailing parts of life in the kingdom. Headings include:

The walled city

Coffin, Yves, 1924-2016. (1960). [Northern gates of Angkor Thom, view from the south] [picture] / Yves Coffin. https://nla.gov.au/nla.obj-140374407

Coffin, Yves, 1924-2016. (1960). [Gates of Angkor Thom, view from southern gate, rows of sculptures line entrance gate] [picture] / Yves Coffin. https://nla.gov.au/nla.obj-140374100

Coffin, Yves, 1924-2016. (1960). [Preah Vihear, head of Nagas as balustrades] [picture] / Yves Coffin. https://nla.gov.au/nla.obj-140373655

‘The walls of the city [Angkor Thom] are about twenty li in circumference. There are five gateways, each of them with two gates, one in front of the other.’

‘Around the outside of the city walls there is a very large moat. This is spanned by big bridges carrying large roads into the city.’

‘The five gateways of the city are all alike; the parapets of the bridges are all made of stone and carved into the shape of snakes, each snake with nine heads. Fifty-four deities are all pulling at the snake with their hands, and look as if they are preventing it from escaping.’

‘Lu Ban Tomb [Angkor Wat] is about one li beyond the south gate. It is about ten li in circumference and has several hundred stone chambers.’

‘Ten li east of the city wall lies the Eastern Baray. It is about a hundred li in circumference. In the middle of it there is a stone tower with stone chambers. In the middle of the tower is a bronze reclining Buddha with water constantly flowing from its navel.’

Dwellings

Coffin, Yves, 1924-2016. (1960). [Angkor Wat, view of third gallery with reliefs] [picture] / Yves Coffin. https://nla.gov.au/nla.obj-140375750

Coffin, Yves, 1924-2016. (1960). [Angkor Wat, steps of temple] [picture] / Yves Coffin. https://nla.gov.au/nla.obj-140372307

Coffin, Yves, 1924-2016. (1960). [Angkor Wat gallery] [picture] / Yves Coffin. https://nla.gov.au/nla.obj-140372454

‘The Royal Palace, officials’ residences, and great houses all face east. The Palace lies to the north of the gold tower with the gold bridge, near the northern gateway. It’s about five or six li in circumference.’

‘Inside the palace, there is a gold tower, at the summit of which the king sleeps at night. The local people all say that in the tower lives a nine-headed snake spirit which is lord of the Earth for the entire country.’

‘The dwellings of the king’s relatives and senior officials are large and spacious in style, very different from the ordinary people’s homes. The roofs are made entirely of thatch, except for the family shrine and the main bedroom, both of which can be tiled.’

‘The homes of the common people have roofs made only of thatch. They dare not put up a single tile. Although their houses vary in size depending how wealthy they are, they dare not build houses to rival the official residences.’

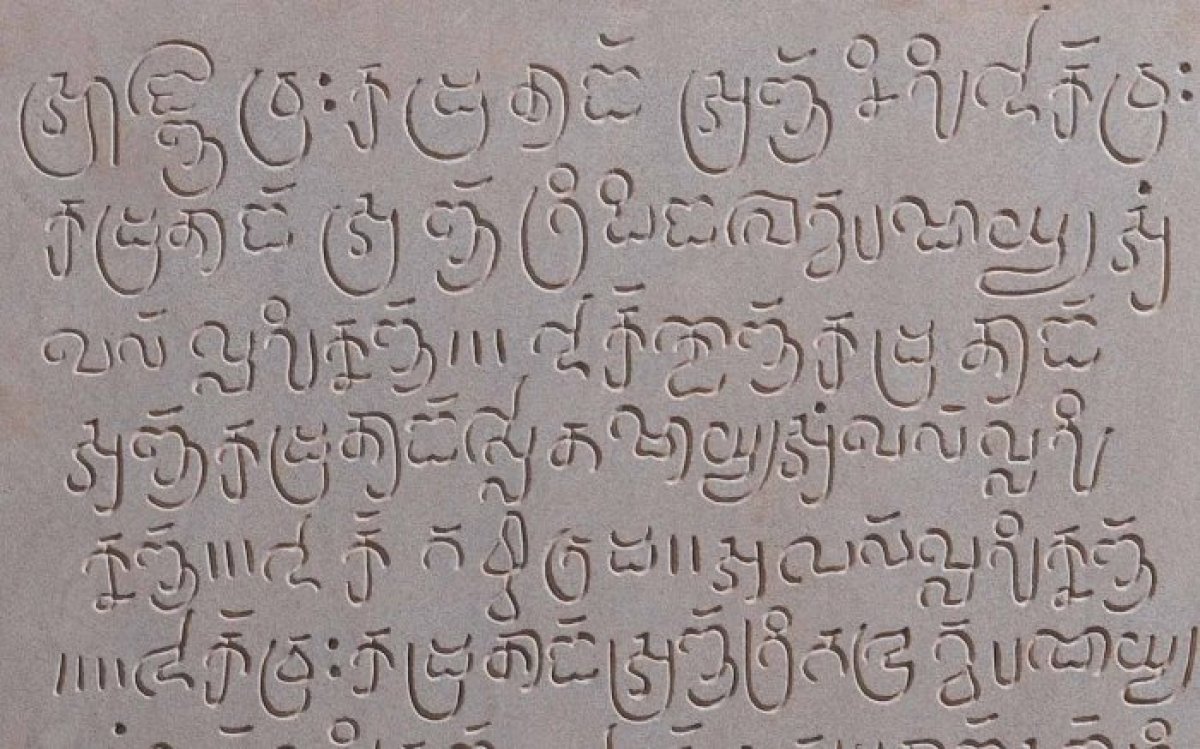

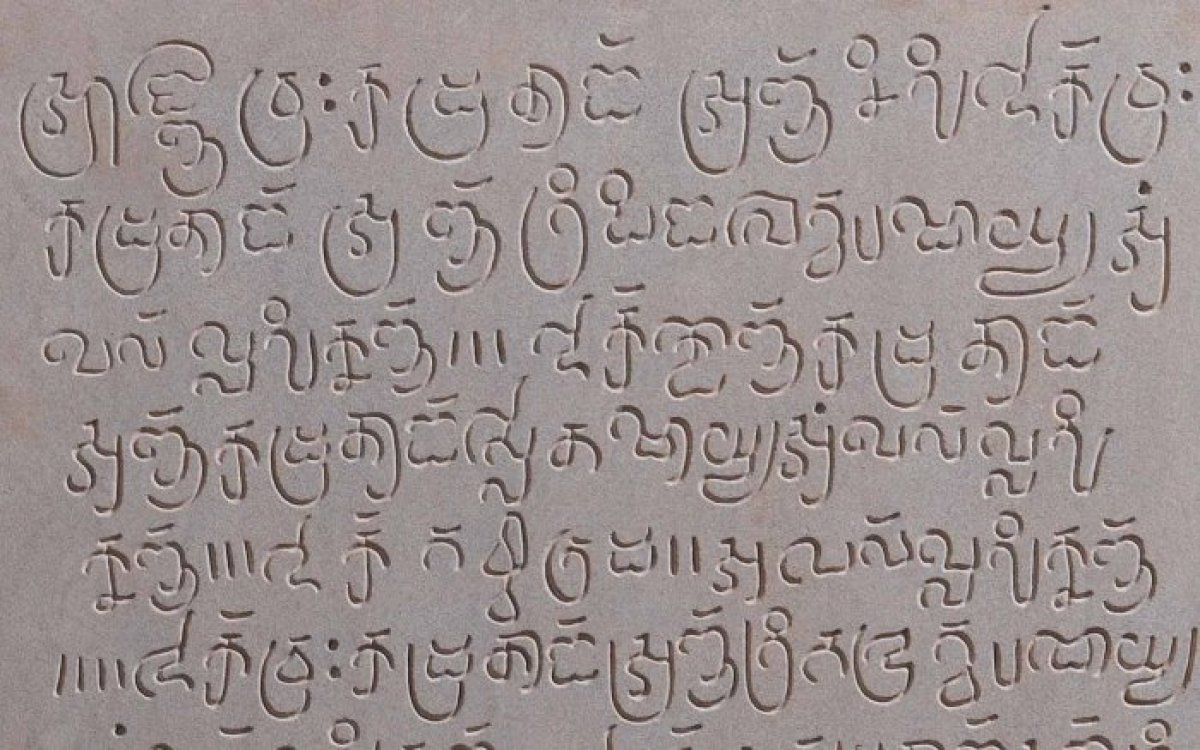

Writing

(2010). [Replica of Inscribed Khmer stele]. Siem Reap, Cambodia : [S.n.] https://nla.gov.au/nla.cat-vn4823973

‘Everyday writing and official documents are all done on the skin of muntjacs, deer, etc, that is dyed black.’

‘To write, people use a kind of powder like chalk, which is rolled into a little stick called suo. The markings can be erased using something wet.’

Trade

‘The local people who know how to trade are all women.’

‘There is a market every day from around six in the morning until midday. There are no stalls, only a kind of mat laid out on the ground. I gather there is a rental fee to be paid to officials.’

‘Market transactions for items of small value are paid for with rice or other grains. Higher value transactions are paid for with cloth. The largest transactions are done with gold and silver.’

Sought-after Chinese goods

‘They do not produce gold or silver in Cambodia, I believe, and so they hold Chinese gold and silver in the highest regard..’

‘The people of Cambodia value items made of fine double-threaded silk in various colours. They also value such things as pewter ware from Zenzhou, lacquerware dishes from Wenzhou and celadon ware from Quanzhou.’

‘Beans and wheat are particularly sought after, but they cannot be taken there.’

Activities

1. The account of Zhou Daguan is the only surviving eyewitness account we have of what life was like in the Khmer Empire. It is a vital part of our understanding of this time. However, relying on one account only can have its drawbacks. Consider what problems might arise from relying on one source of information. Create a list.

2. Zhou Daguan wrote his account of life in Cambodia in the late thirteenth century. His original report was written in Chinese. Although his text is still understandable today, the dialects and words used by Zhou have evolved or become obsolete. What problems could this cause when reading or translating the document?

The original Chinese was translated into French in the nineteenth century. From the French translation, English translations were made. How might this impact the accuracy of the report?

To demonstrate this simply, take one of Zhou’s comments in this unit and paste it into Google Translate. Translate it into another language. Translate that language into another language then translate it back to English. Has anything changed? Is it still understandable? Have the meanings of the words changed?

3. There are no original Khmer documents surviving due to the nature of the materials on which they were written and the climate of the country. Think about the materials used to write on today. What conditions might be best to keep them so they survive into the future. A lot of information is stored digitally these days. What problems might face digital media over time? What steps could we take to ensure our data is safe for the future?