For the first two centuries of their rule, the Tokugawa Shogunate ruled Japan within a strictly enforced feudal system. Within Japan, social order was strictly codified and enforced, with little to no movement between classes. Through the sakoku policies, input from western and other external powers was regulated and manipulated to bolster the position of the government. However, by the dawn of the nineteenth century, policy makers and social commentators felt a growing sense of instability and national crisis.

The government, in its aim to regulate matters, failed to keep up with social changes, and the economic policies of the government were causing stagnation, especially in the now densely populated urban areas. Discontent directed towards the central government grew as the nineteenth century dawned. This period of the shogunates’ decline is known as the Bakumatsu (幕末 – The Final Act / The end of the Bakufu).

Osaka Rebellion

In 1833 and 1836, the agricultural sector was in crisis with poor harvests across the Kansai district, driving up the cost of rice and basic food staples which, in turn, drove taxes higher. Traditionally a highly fertile and productive region, the people of the Kansai district were not used to food shortages and were quick to show their displeasure with the government. Large bands of peasants began destroying neighbourhoods and private property throughout Osaka.

Oshiro Heihachiro, a scholar and government official who was openly critical of the Tokugawa Government and its policies, used his connections and administrative experience to direct the anger of the peasants towards the Government rather than random acts of destruction. On the night of 7 February, 1837, Heihachiro set fire to his house as a signal to start the coordinated attack. On his signal, his followers were to burn tax offices and break into food storehouses and distribute their contents to the hungry population. The bakufus sent troops to counter the rebellion and, despite both sides being poorly prepared, the bakufu troops managed to put down the uprising. Heihachiro fled Osaka but took his own life before he could be captured and tortured by government troops. The uprising failed, but the hostility against the government remained.

Osaka Rebellion

In 1833 and 1836, the agricultural sector was in crisis with poor harvests across the Kansai district, driving up the cost of rice and basic food staples which, in turn, drove taxes higher. Traditionally a highly fertile and productive region, the people of the Kansai district were not used to food shortages and were quick to show their displeasure with the government. Large bands of peasants began destroying neighbourhoods and private property throughout Osaka.

Oshiro Heihachiro, a scholar and government official who was openly critical of the Tokugawa Government and its policies, used his connections and administrative experience to direct the anger of the peasants towards the Government rather than random acts of destruction. On the night of 7 February, 1837, Heihachiro set fire to his house as a signal to start the coordinated attack. On his signal, his followers were to burn tax offices and break into food storehouses and distribute their contents to the hungry population. The bakufus sent troops to counter the rebellion and, despite both sides being poorly prepared, the bakufu troops managed to put down the uprising. Heihachiro fled Osaka but took his own life before he could be captured and tortured by government troops. The uprising failed, but the hostility against the government remained.

The Black Ships

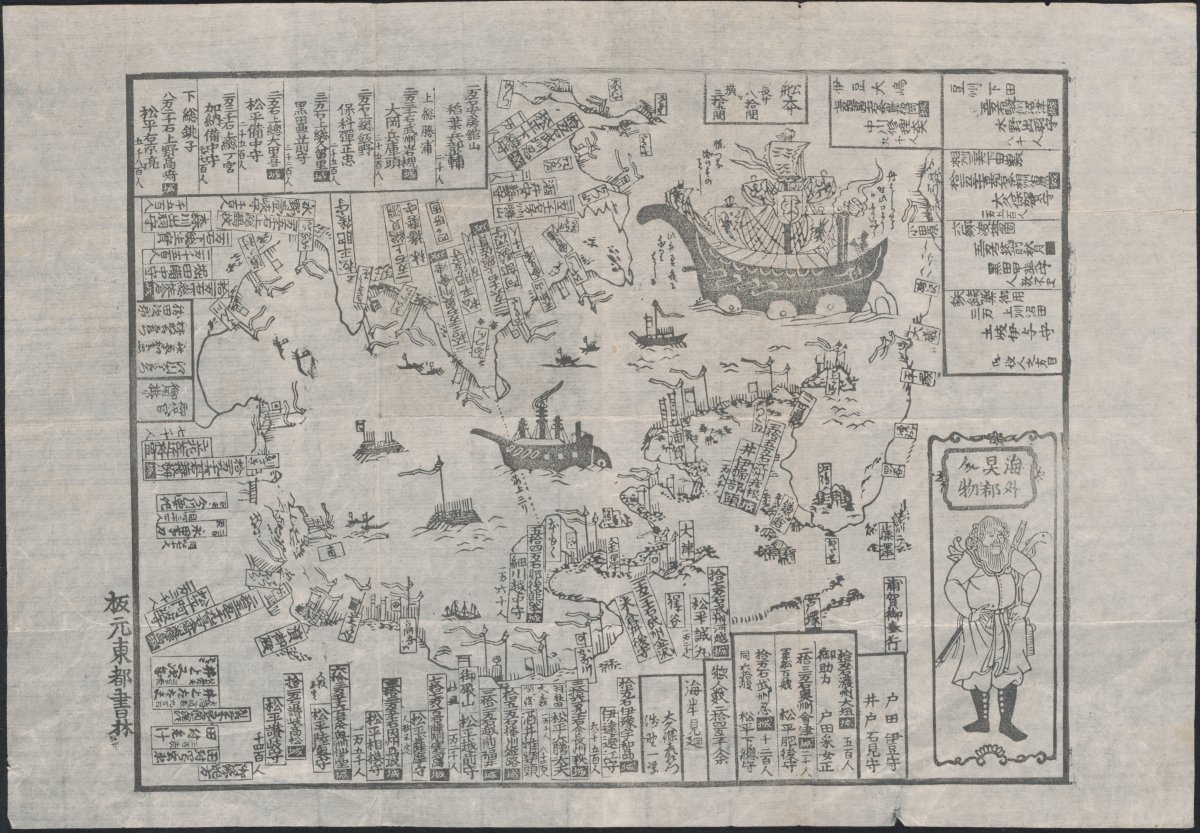

Pressure from the outside was growing, with a series of American and British ships entering Japanese waters in direct opposition to the Closed Country policy. Debates surfaced about whether the aging Tokugawa government was capable of dealing with the threats, perceived or actual, that were facing Japan. In 1844, the King of the Netherlands, William II, wrote to the Shogun expressing his concern that Japan should reconsider the Closed Country policy, otherwise they may be forced to open by outside forces (particularly Russia, the USA or the British). The Shogun refused. However, within a decade, the King’s concern would be realised.

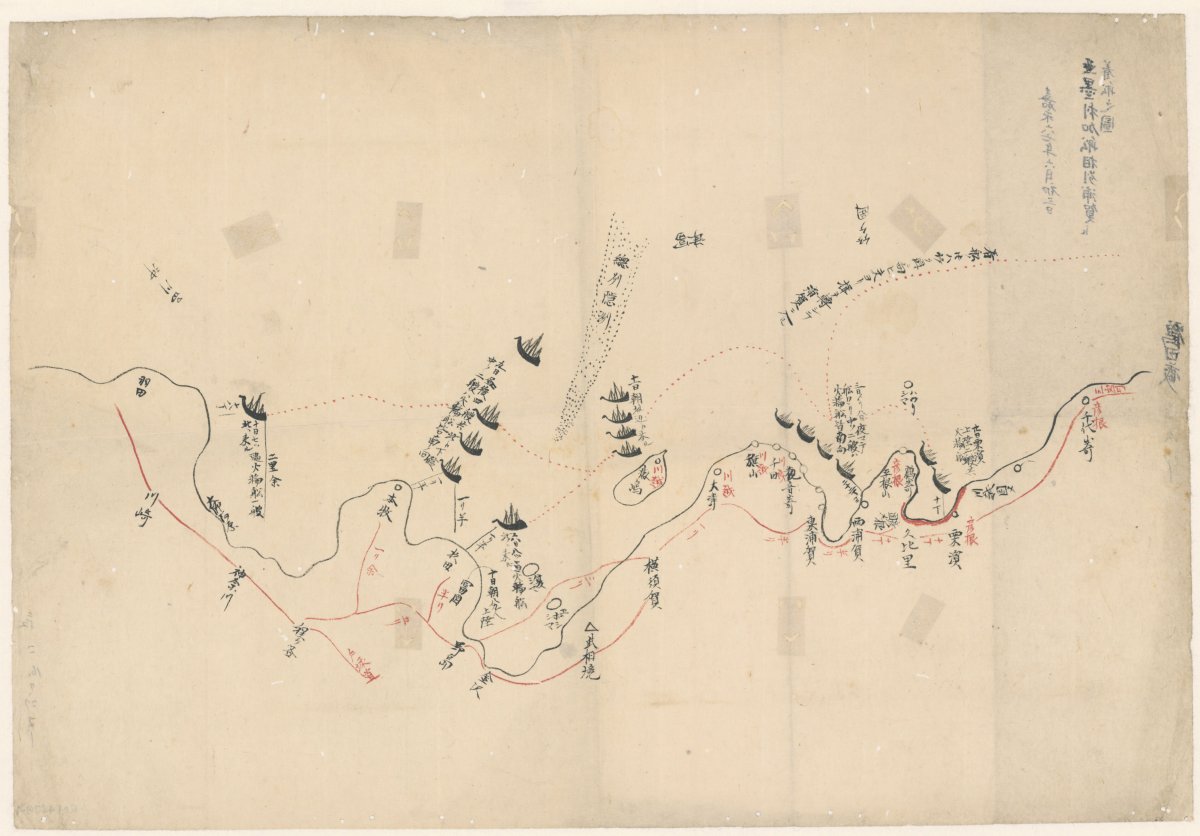

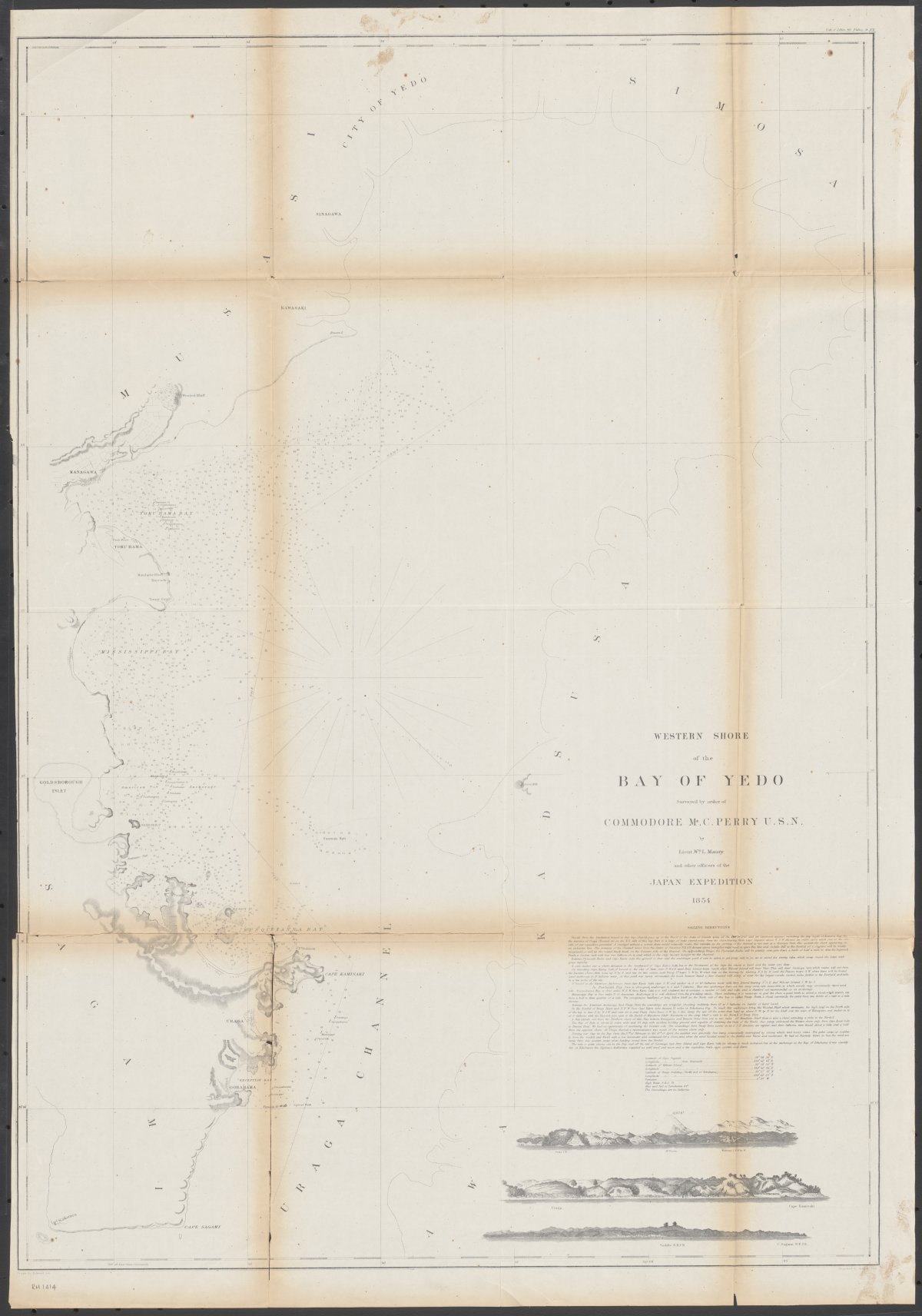

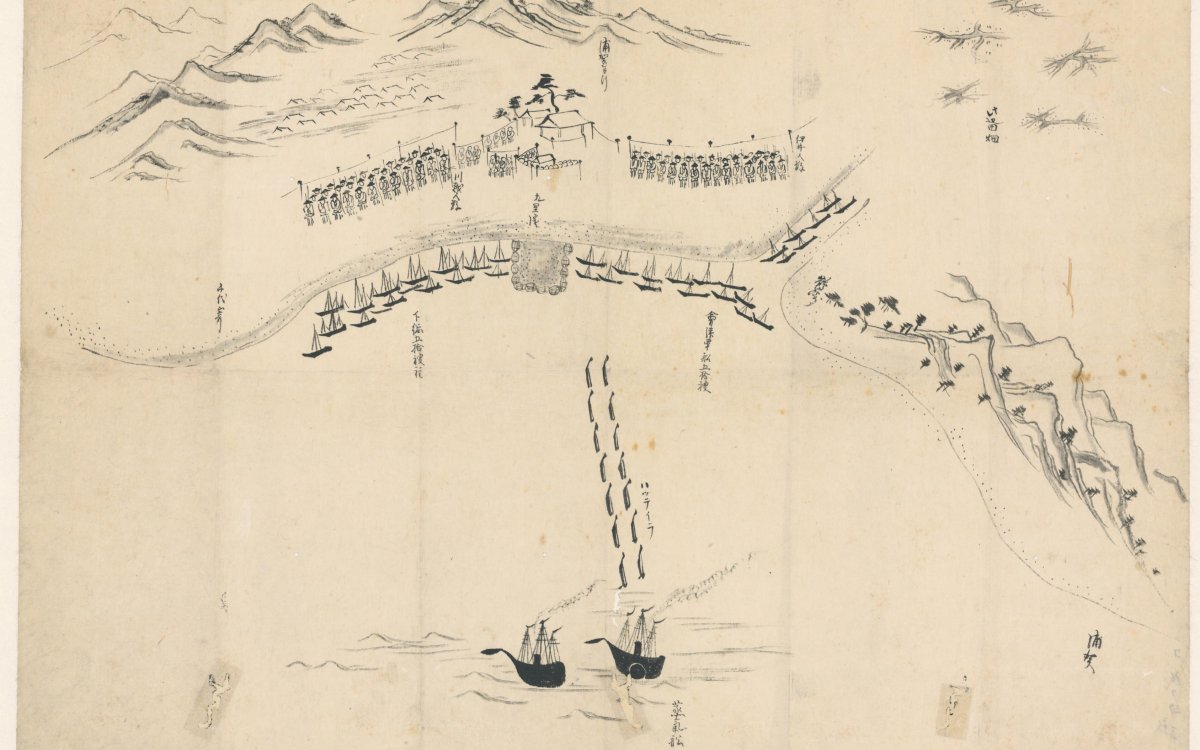

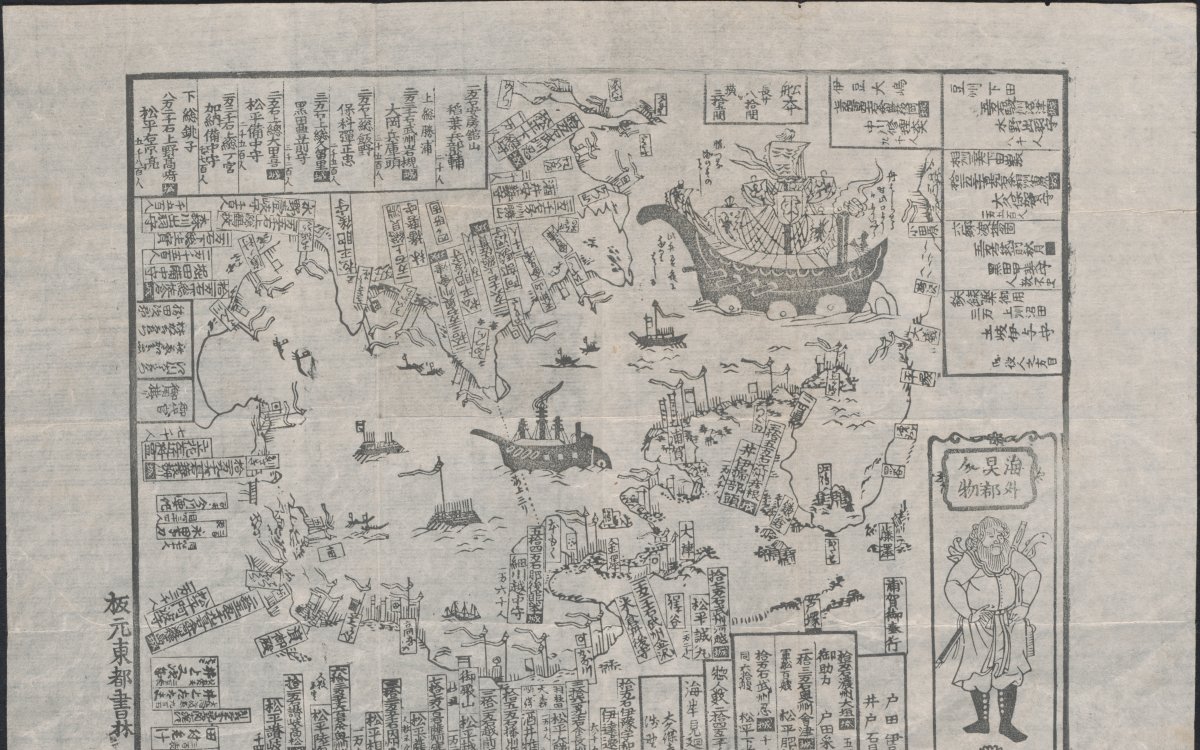

On July 8, 1853, four large ships sailed into the Uraga Channel, the entrance to Tokyo Bay, and anchored within sight of the village of Uraga. These ships, the USS Mississippi, Plymouth, Saratoga and Susquehanna, were ships of the United States Navy under the command of Commodore Matthew Perry. These ships became known as the kurofune (黒船 – Black Ships) for the black colour of the hulls of the old sailing vessels and the black smoke that poured from the funnels of the steam ships.

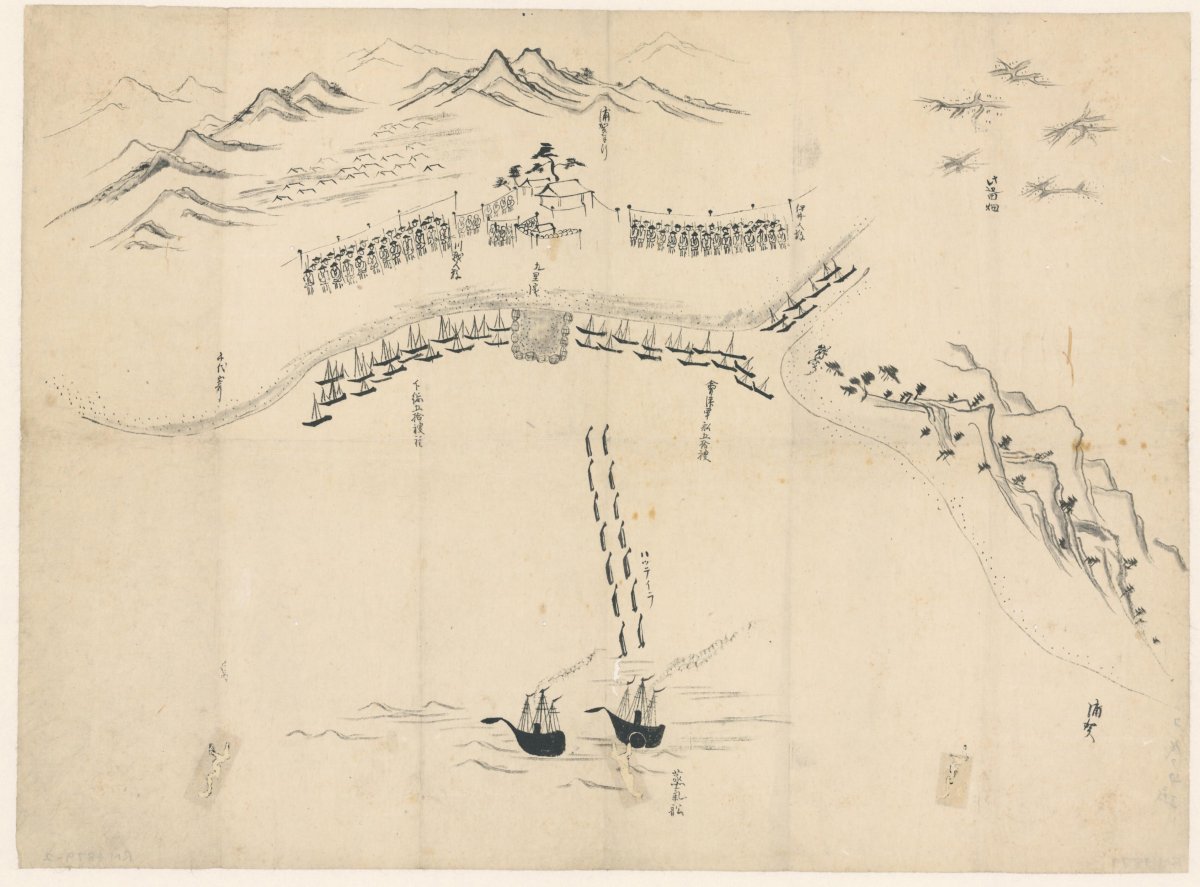

(1853). [Birds-eye view of first landing at Kurihama Beach near Uraga, Tokyo Bay, July 14 1853, by US Navy Commodore Matthew Perry, Special American Diplomatic Expedition]. http://nla.gov.au/nla.obj-416708697

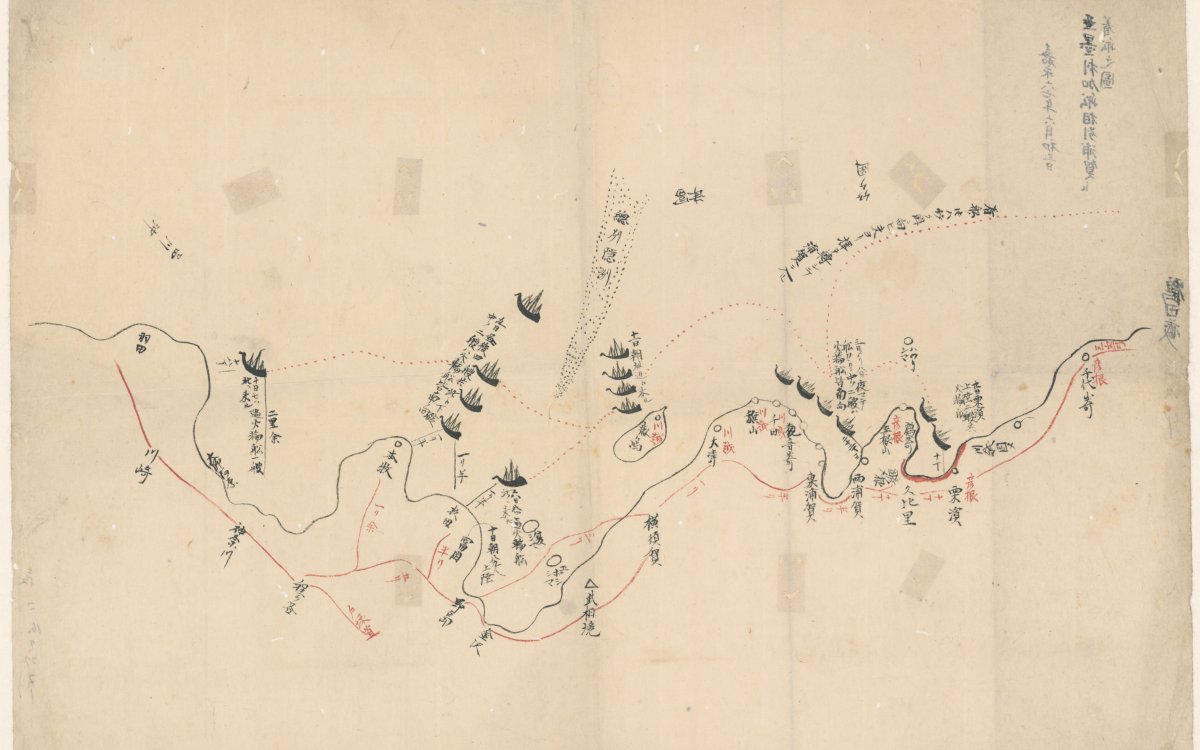

(1853). Map of American ships arriving at Uraga. http://nla.gov.au/nla.obj-416708988

Several attempts were made by officials from Uraga to send the ships away. However, Perry refused to leave. He proclaimed that he had brought with him a letter from the US President, Millard Fillmore, and would only be satisfied when he could speak to a dignitary of the highest rank who could arrange for the letter to be delivered to the Emperor.

In line with bakufu policy, the Japanese officials told Perry he must sail to Nagasaki, as all foreign business was to be conducted through Deshima Island. Perry refused and threatened to sail to Edo and deliver the letter to Edo Castle himself. Further refusal from the Japanese led Perry to threaten the use of force if his requests were not met. After six days of intense negotiation, Perry and his men were received in the small village of Kurihama by two high officials, the Governor of Uraga and the Shogunate Minister from Edo.

The bakufu instructed the lords of Uraga and surrounding domains to muster their troops and prepare for any aggression from the Americans. However, in a display of bloodless military pageantry, Perry presented President Fillmore’s letter, along with his own letters of credence to the assembled officials in Kurihama. The officials promised to forward the letter to the Emperor, but noted that, as the letter was not received at Deshima where all foreign business must take place, no negotiation or entertainment could take place. The Americans’ business was complete; they would now have to leave.

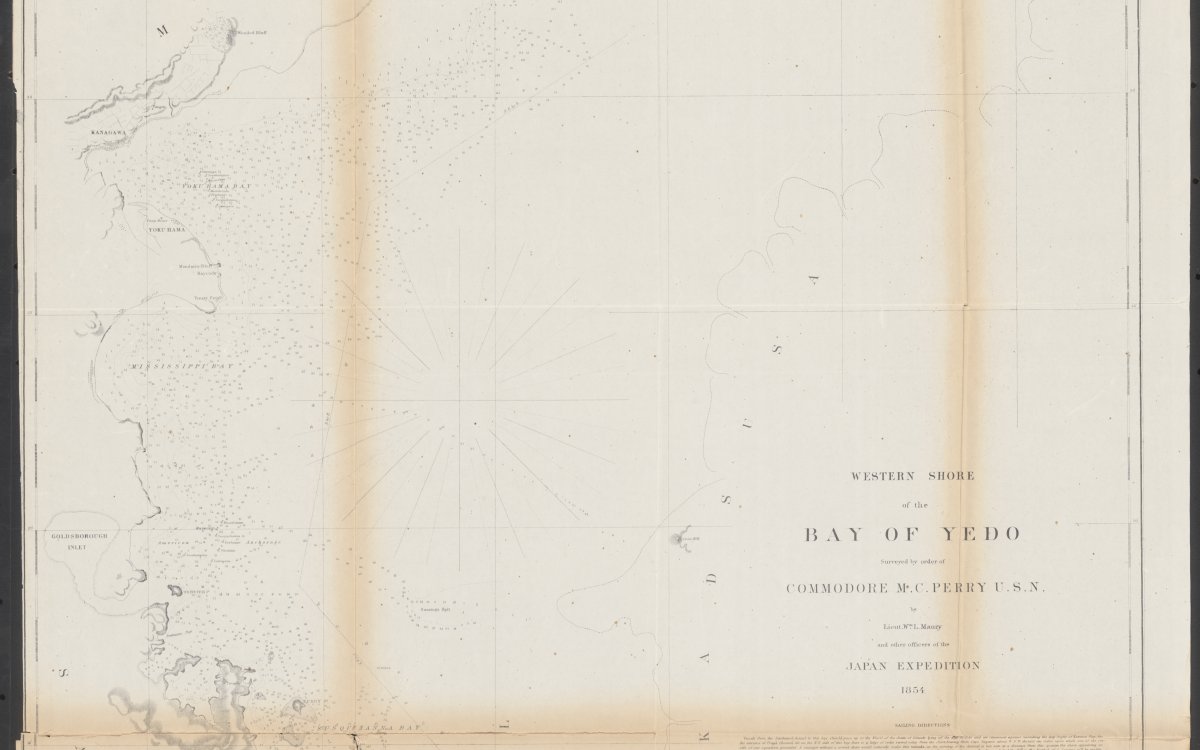

United States. Hydrographic Office & Perry, Matthew Calbraith, 1794-1858 & Siebert, Selmar & Bien, Julius, 1826-1909 & Sels, Edward & Maury, William L. (1854). Western shore of the Bay of Yedo [cartographic material] / surveyed by order of Commodore M.C. Perry U.S.N. by Lieut. Wm. L. Maury and other officers of the Japan Expedition 1854 ; drawn by Edward Sels ; engraved by Selmar Siebert. http://nla.gov.au/nla.obj-231475240

[Edo-wan okatame no zu] [picture]. http://nla.gov.au/nla.obj-151489510

After a further three days of surveying and mapping the Japanese coast, Perry and his fleet left Japanese waters on 17 July, 1853. Perry and his Black Ships returned a year later, a visit which resulted in the bakufu signing the Convention of Kanagawa which established direct diplomatic relations with the United States.

Four years later, in 1858, the Harris Treaty was signed by the United States and Japan, establishing trade, navigation and formal diplomatic relations between the two nations. This treaty with the United States was quickly followed by similar treaties with other Western nations. While the fear of aggression from the American ships receded with the signing of these conventions, the bakufu’s acceptance of Perry’s terms and the acceptance of his letter had revealed how unprepared the Shogunate was and how vulnerable their policies were to pressure from the outside. The opening of Japan, keikoku (開国 – Open Country), would fuel a civil war and bring down the Shogunate.

Sonnō jōi

Utagawa, Yoshikazu, active 1848-1863 & 歌川芳員, active 1848-1863. (1860). Gokakoku no uchi Igirisu nyonin [picture]. http://nla.gov.au/nla.obj-151442463

In the years following keikoku, distinct political factions emerged. Pro-western groups studied ideas like democracy, free trade and western science. They advocated that modernisation was the only way Japan could survive. Pro-western daimyos such as Ii Naosuke, who was acting as regent for the 14-year-old Shogun,Tokugawa Iemochi, sent 77 samurai to the United States to learn what they could about that country’s military and civic matters. Naosuke also led purges of government officials whom he saw as insufficiently loyal to the bakufu through their anti-western sentiment. Those who were part of the anti-western factions rallied under the slogan of Sonnō Jōi ( 尊皇攘夷– Revere the Emperor, Expel the Western Barbarians).

In 1863, the Emperor Komei issued the ‘edict to expel the barbarians’ which essentially directed all foreigners to leave Japan. This marked a departure from more than 200 years of political inaction from the emperor in Kyoto. Anti-western factions openly confronted or even attacked foreigners in the streets. Some went as far as attacking Japanese citizens who were seen to be consorting with or admiring westerns and their ideas. Ii Naosuke was murdered in the street for his pro-western stance and in retaliation for his own attacks.

When Tokugawa Iemochi died at age 20 in 1866 the new Shogun, Tokugawa Yoshinobu, tried to find a middle ground by reorganising the political power structure in a way that would appease those loyal to the Emperor, but keep the Shogun in command. His attempts failed and in 1867, Yoshinobu abdicated as Shogun reasoning that, unless the government was controlled by one central authority (the Imperial Court) the nation would fail. The Shogun’s resignation came as something of a shock to the court. With no alternative in place, the Imperial Court permitted the Shogun (and the Tokugawa clan) to continue administering the country until a plan could be devised. Despite Yoshinobu’s decision, pro-shogun forces still remained loyal.

The internal conflict came to a head with the Boshin War (1868–1869) in which those loyal to the Shogunate were challenged by those seeking to place the new young Emperor Meiji (1852–1912) on the throne and to restore imperial rule.

Taiso, Yoshitoshi, 1839-1892 & 大蘇芳年, 1839-1892. (1877). Kagoshima bōto shōzō ryakuden [picture]. http://nla.gov.au/nla.obj-152241305

An alliance of powerful daimyos from Satsuma, Choshu and Tosa sided with the Emperor and helped the Court secure their powerbase in Kyoto. This alliance promoted the philosophy of abolishing the Shogunate and the Bakumatsu, confiscating the lands of the Tokugawas and a full restoration of all power to the Imperial Court and Emperor. Tokugawa Yoshinobu declared he would not be bound by this restoration and prepared to attack Kyoto.

Conflict between both sides culminated at Battle of Toba–Fushimi, between Osaka and Kyoto. The battle lasted for four days. Despite being outgunned, the troops loyal to the Emperor prevailed with their more modern weaponry. The Battle of Toba–Fushimi was a decisive victory for the imperial loyalists. A number of pro-Shogunate forces retreated and set up a short-lived resistance in Hokkaido (then called Ezo). Their resistance ended after five months with the Battle of Hakodate.

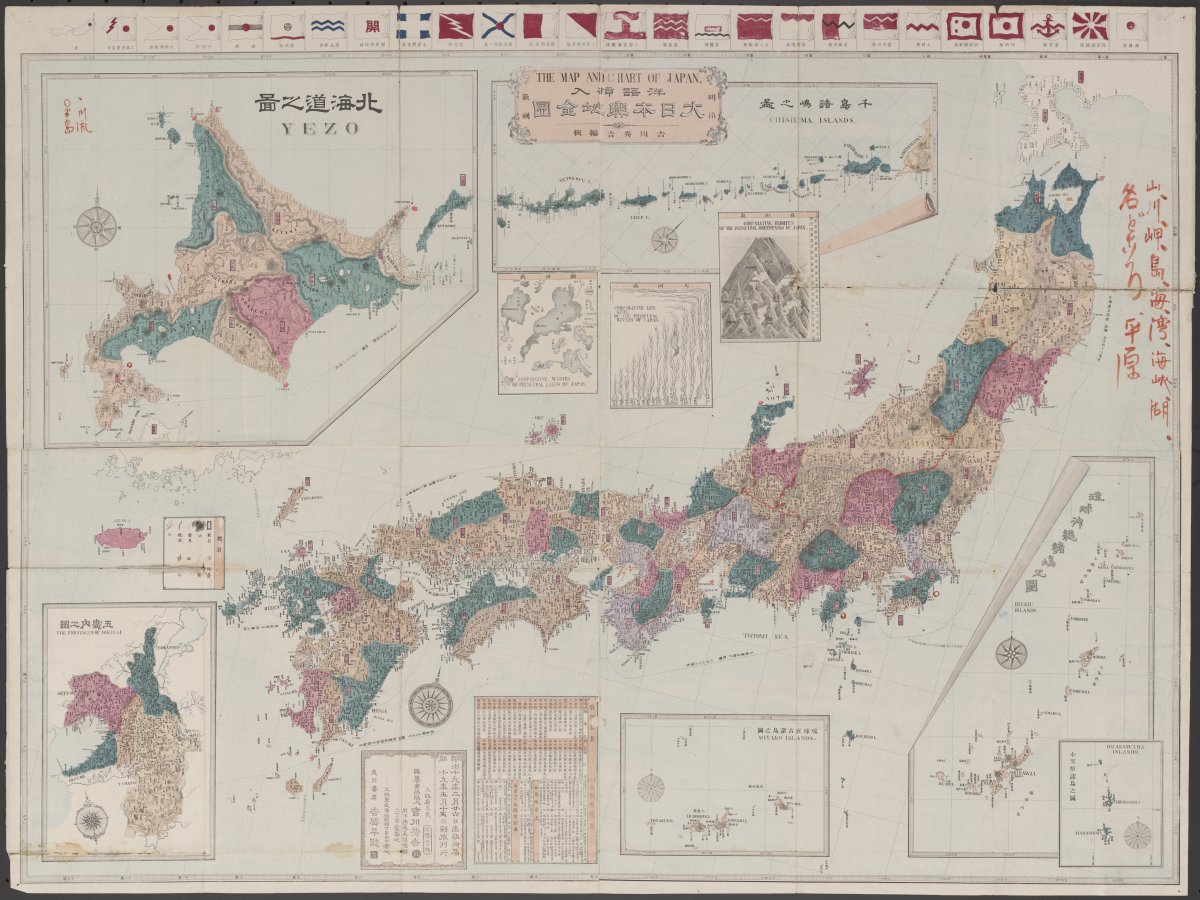

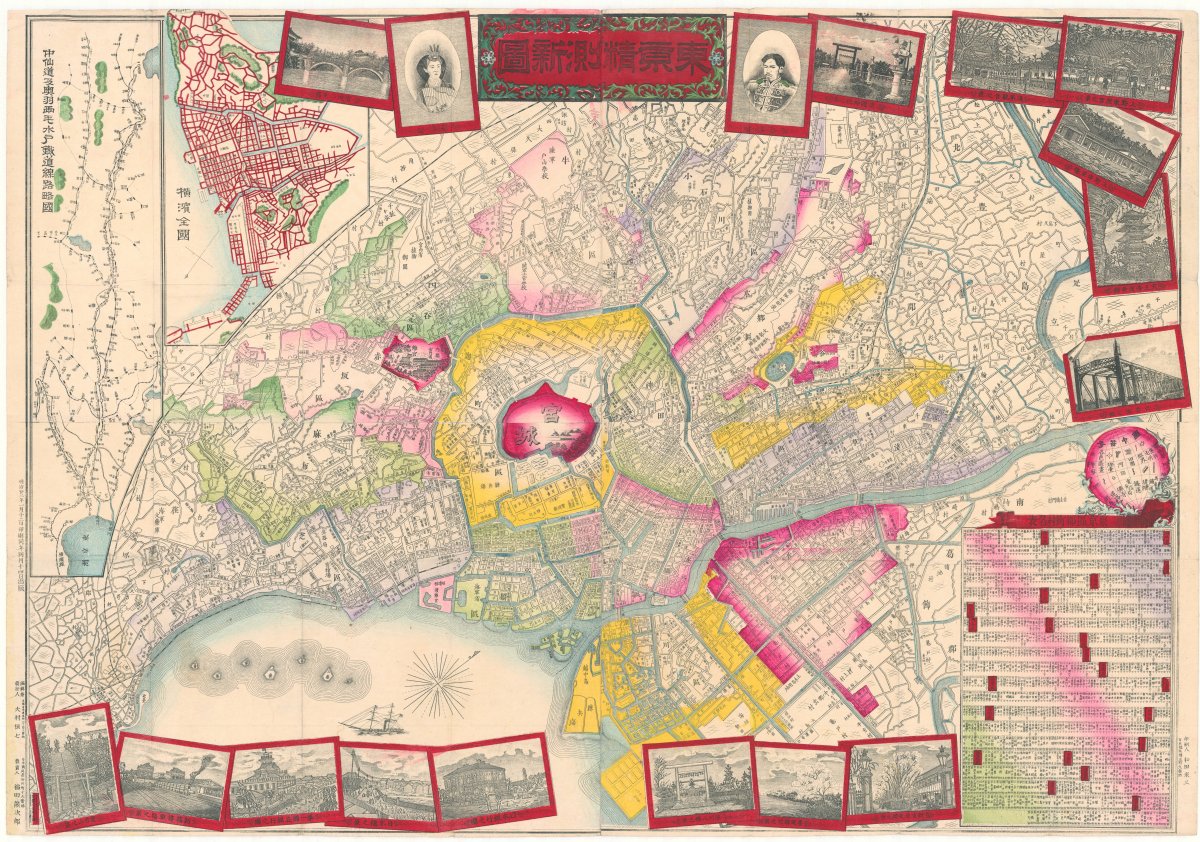

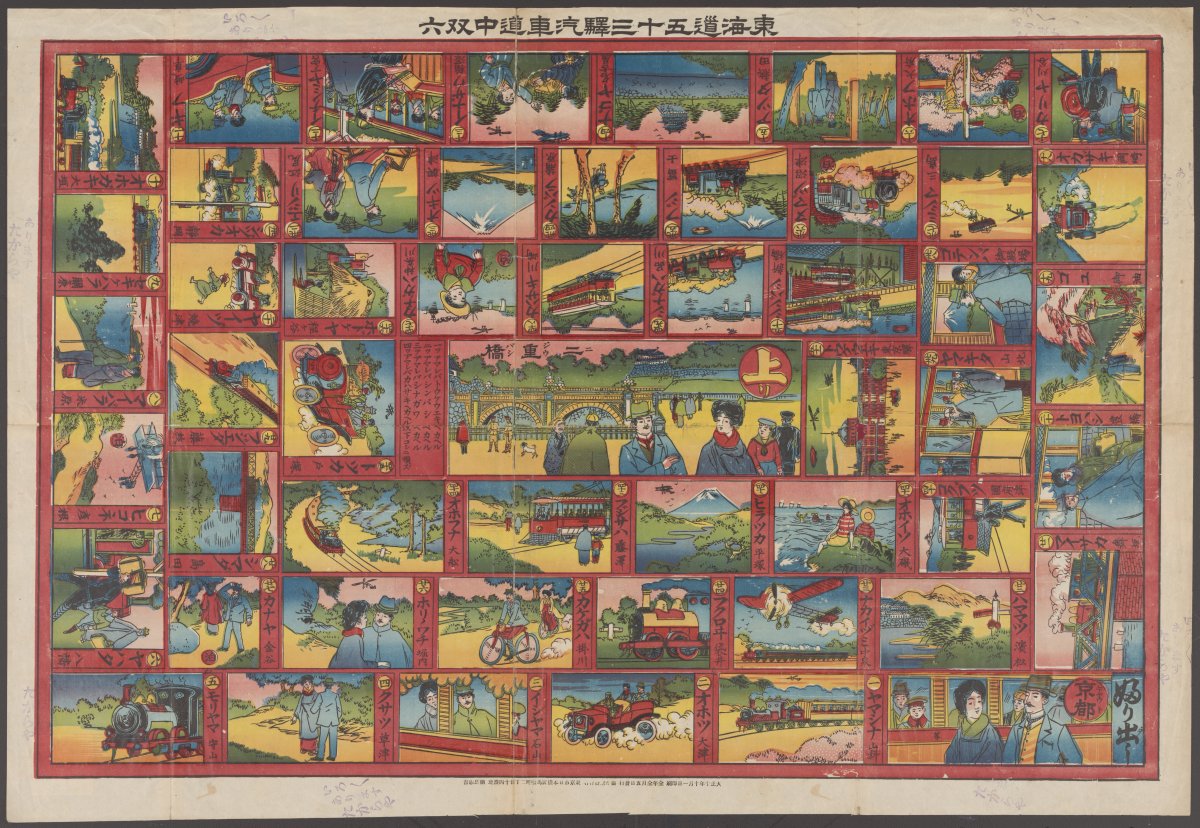

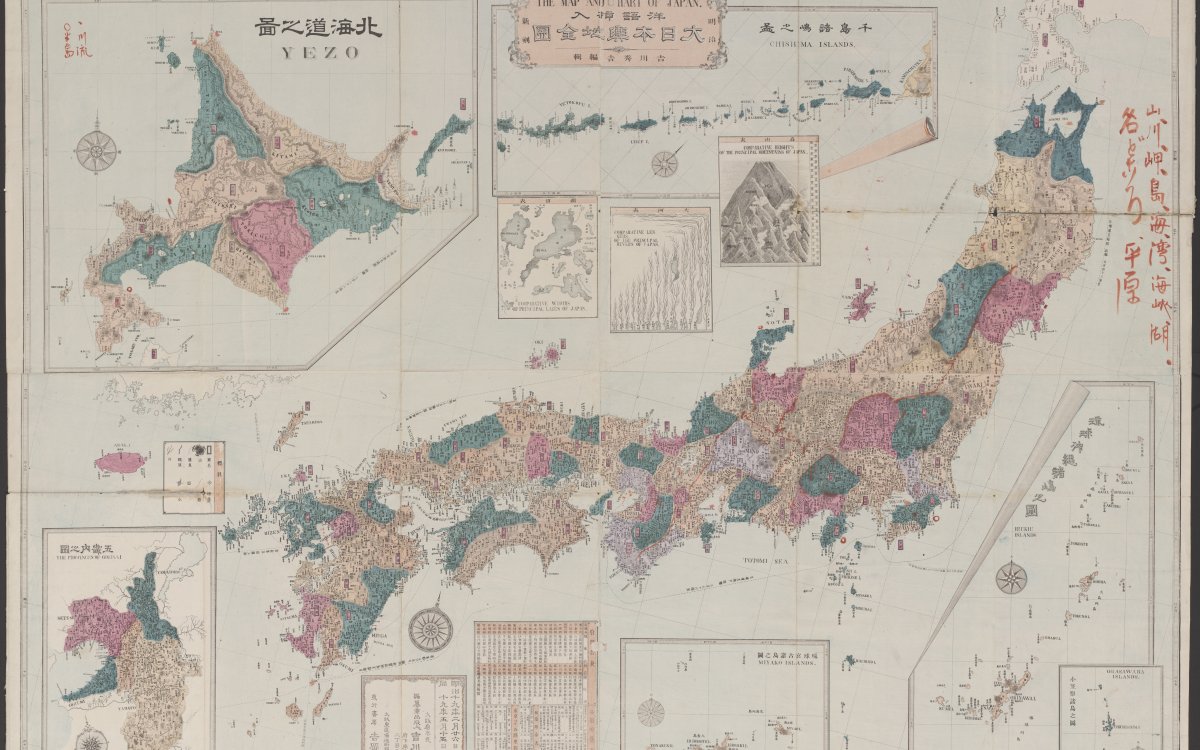

With the defeat of the Shogunate forces, the Meiji Restoration took place. Tokugawa Yoshinobu was stripped of his power and lands (although he would later be pardoned and given the title of Prince). The imperial system was restored for the first time since the short-lived Kenmu Restoration in 1333. Under Emperor Meiji, Japan accelerated its program of industrialisation, modernisation and social reform including, curiously, adopting some western dress and social norms. The slogan of Sonnō Jōi was replaced with Fukoku Kyōhei (富国強兵 – Enrich the country, strengthen the military). New industries such as shipyards and foundries were established and adopted western technology to improve production, and public services such as education were promoted for all classes. Rapid industrialisation saw the beginnings of Japan’s extensive railroad network and establishment of national communication systems. Western technology and ideas were also incorporated into military training and weaponry. The armed forces were further strengthened by the imposition of nationwide conscription and Japan soon came to see itself as a military power with victories in the Sino–Japan war and the Russo–Japan war.

Yoshikawa, Hidekichi & 吉川秀吉. (1886). Meiji shinkoku yōgo sōnyū Dai Nihon yochi zenzu = The map and chart of Japan / Yoshikawa Hidekichi henshū; Araga Seiichi kōetsu. http://nla.gov.au/nla.obj-232447345

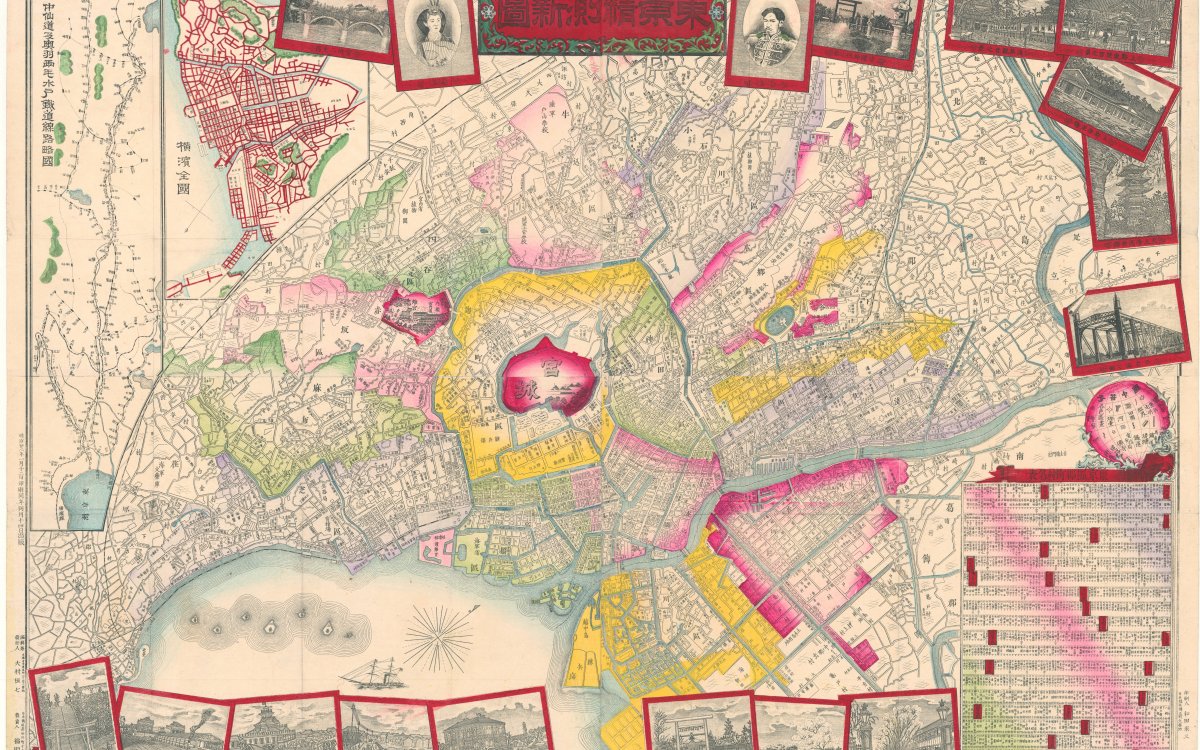

Ōmura, Tsuneshichi & 大村恒七 & Fukuda, Kumajirō & 福田熊次郎. (1888). Tōkyō seisoku shinzu / Ōmura Tsuneshichi henshū ken hakkōnin. http://nla.gov.au/nla.obj-387373979

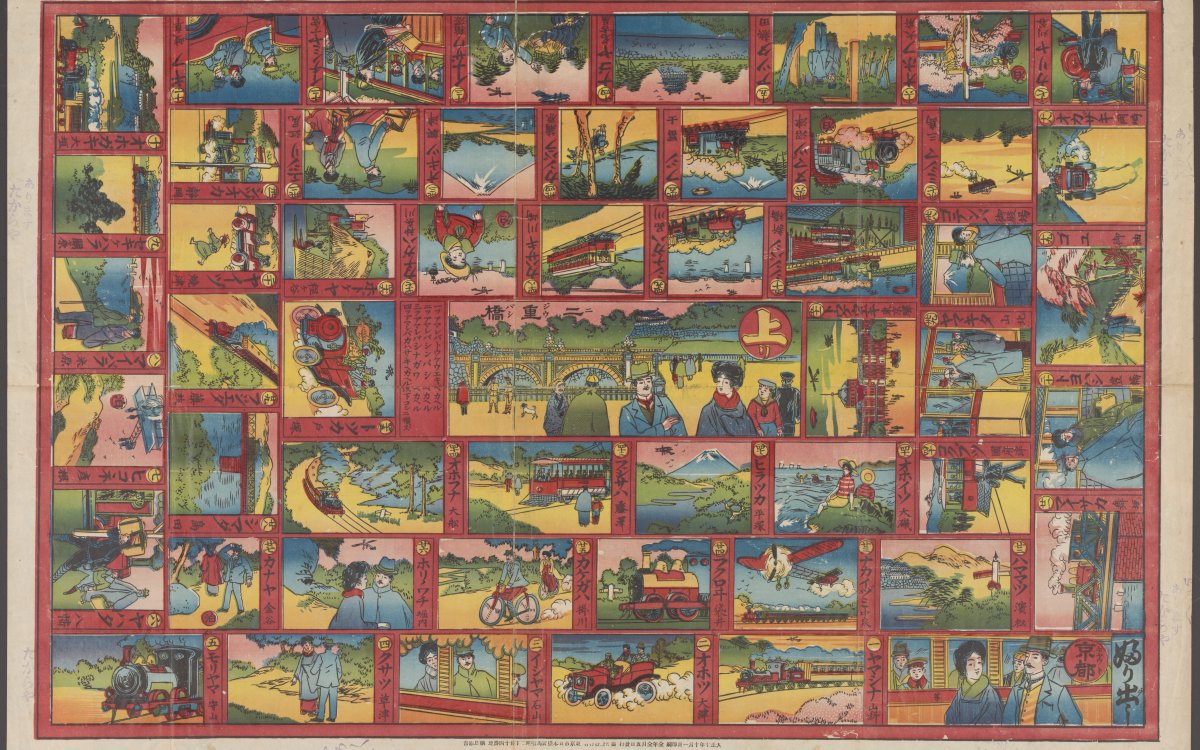

Tsunashima, Kamekichi & 綱島亀吉. (1921). Tōkaidō gojūsan-eki kisha dōchū sugoroku [picture] / Tsunashima Kamekichi hen. http://nla.gov.au/nla.obj-151637652

Yōsai, Nobukazu, 1872-1944 & 楊斎延一, 1872-1944. (1900). Kōi konreishiki no zu [picture]. http://nla.gov.au/nla.obj-151494111

Activities

- Perry’s arrival was a major turning point in Japan’s history and policy. Have students conduct a class debate, one side representing the Japanese government that is opposed to opening the country to the world; the other side representing the Perry expedition who want to begin trading with Japan. Have students consider commercial, cultural, and political implications of their arguments. Students should consider the historical time in which this debate would have taken place and challenge the validity of the prevailing political trends/philosophies, such as colonial expansion, political coercion by imperial powers, the ‘civilising mission’.

- After the Meiji Restoration, Japan underwent rapid industrialisation. What does it mean to be industrialised? What impact does industrialisation have on a country? What are its advantages and disadvantages?