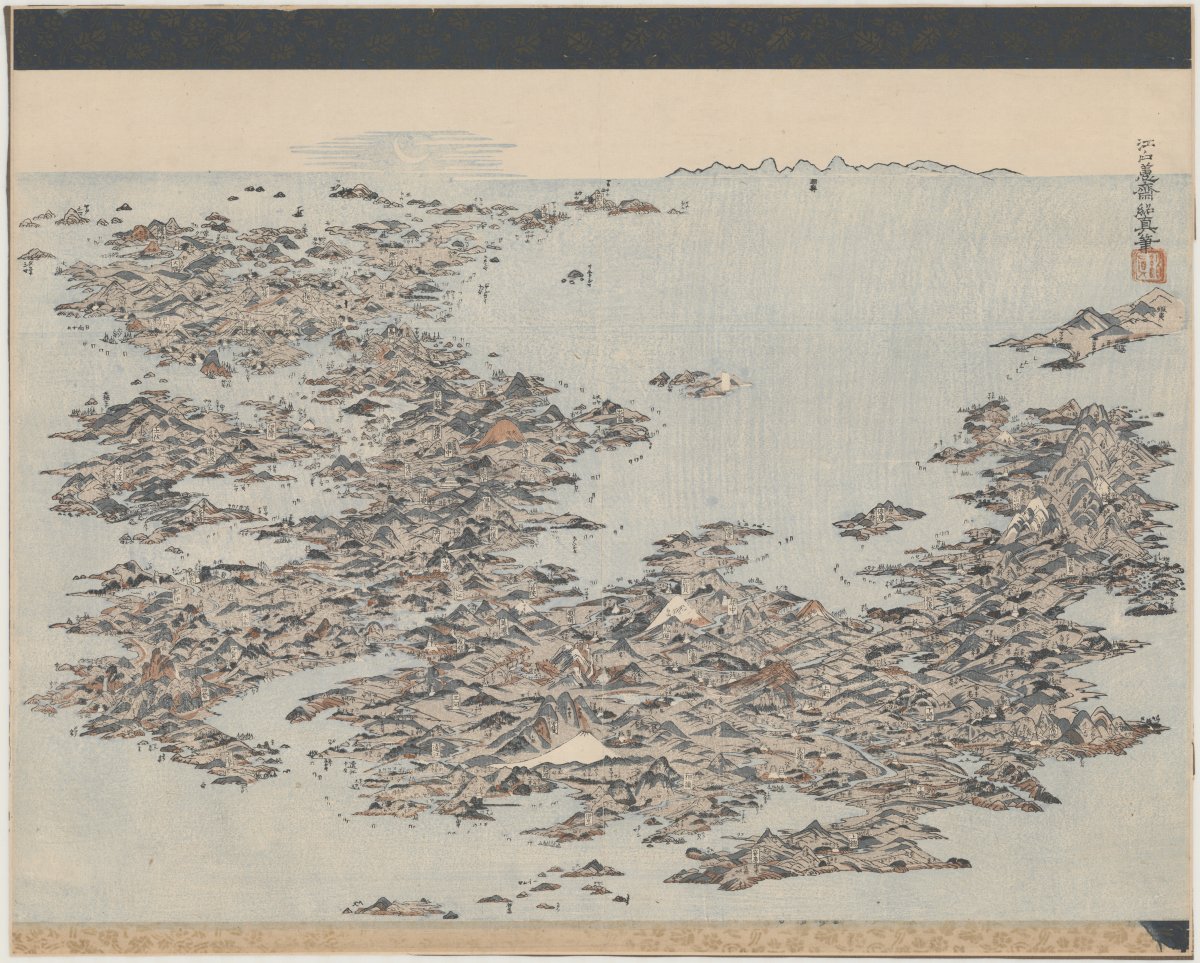

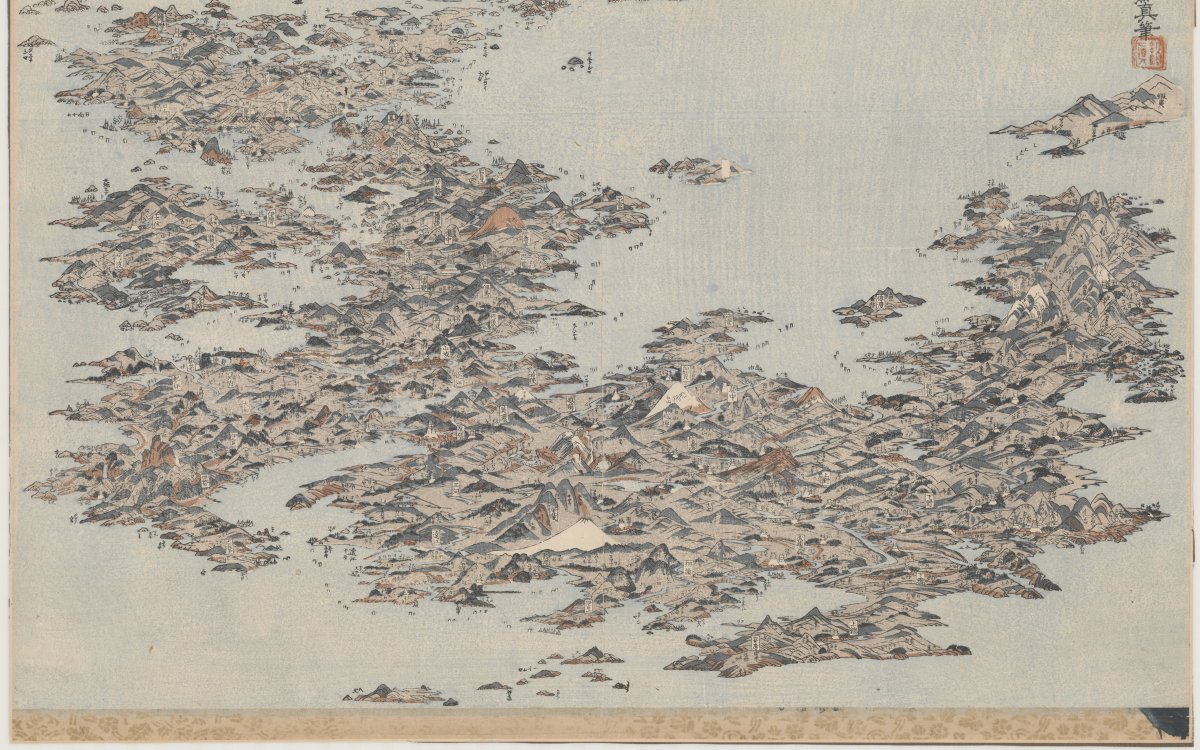

Kitao, Masayoshi, 1764-1824 & 北尾政美 , 1764-1824. (1820). [Nihon meisho no e] [cartographic material] / Edo Keisai Tsugusane hitsu. http://nla.gov.au/nla.obj-248637076

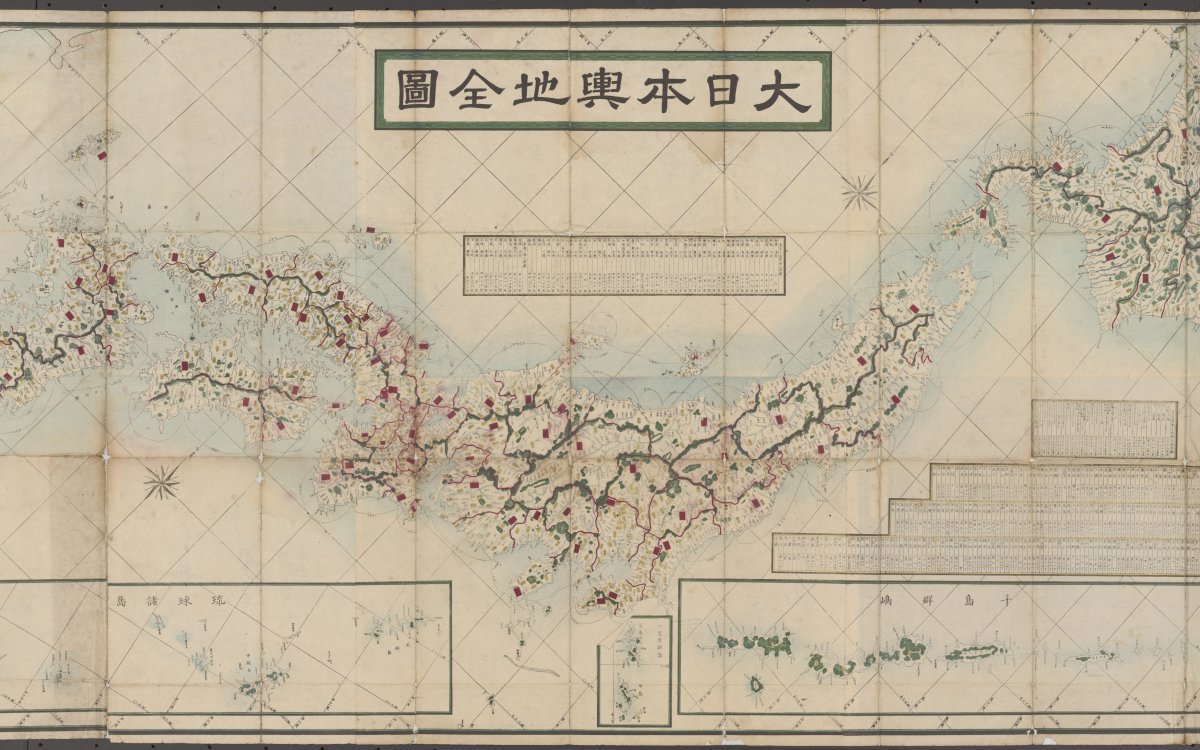

Japan’s geographic location and formation have, of all external forces, had the most profound role in shaping its cultural, political and environmental development. Japan, as we know it today, comprises four main islands (Honshu, Hokkaido, Kyushu and Shikoku (in descending order of size) and a number of smaller island chains including the Ryukyu and Izu–Ogasawara Islands. Throughout history Japanese political power and administrative borders have been shaped by its island nature.

Kodama, Matashichi & 児玉又七. (1879). Dai Nihon yochi zenzu [cartographic material] / Kodama Matashichi. http://nla.gov.au/nla.obj-232448147

From the first evidence of a centralised ‘capital’ and ruler in 500BCE, Japanese society and political infrastructure grew and become more stable across the next five centuries. Across the years, the central court issued a range of political edicts and reforms that aimed to consolidate the central ruling authority of the emperor. These edicts included curtailing the power of regional officials, abolishing private land ownership, codifying a penal system and organising a central bureaucratic system staffed by educated officials. One of the most significant arrangements was the establishing and consolidation of the shōen (庄園), a feudal manor–style arrangement in which large areas of land were granted to officials, who were often friends and family of the emperor. These landowners paid shares of their profits, often to a more powerful member of the court, in order to be exempted from government taxes. As these estates grew in size, so long as they paid their dues they were permitted to function as they saw fit. This system would play a major role in the shift in government in Japan.

Kyoto – Peace Capital

Another significant reform prompted the creation of a new capital which became known as Heian-kyo (平安京 – literally, Peace Capital), and later Kyoto (京都 – Capital City). The construction and move to this new city marked the end of the Nara period which had lasted from 710–794CE and signified the beginning of the Heian period (794–1185CE).

Kyoto – Peace Capital

Another significant reform prompted the creation of a new capital which became known as Heian-kyo (平安京 – literally, Peace Capital), and later Kyoto (京都 – Capital City). The construction and move to this new city marked the end of the Nara period which had lasted from 710–794CE and signified the beginning of the Heian period (794–1185CE).

Throughout the Heian period, the power of the court grew but the emperor's control over the expanding territory didn’t keep up. As the distance from the capital grew, the influence of the emperor and the court diminished. Outside the capital, settlements and societies existed much as they had in the centuries before a centralised state. Some of these people aligned themselves with the emperor and conducted trade and sent tribute, while others remained hostile. Successive emperors sent armies, commanded by military leaders from prominent families to assert their rule and ensure the populations adhered to the emperor’s rule.

Utagawa, Kuniyoshi, 1798-1861 & 歌川国芳, 1798-1861. (1830). Honchō Suikoden gōyū happyakunin no hitori : Eda Genzō Hirotsuna / Ichiyūsai Kuniyoshi ga. http://nla.gov.au/nla.obj-151535028

Once brought under the influence of the central court, the outlying areas and settlements became vassals who, under the administration of regional governors, were expected to provide goods and services to the court including the provision of military forces to the capital. The bulk of military force available to the court was found in the provinces.

Governors spent large amounts of time in the capital, away from their regions. Absentee governors delegated vice-governors, who were almost always drawn from powerful warrior families, with day-to-day provincial administration. Selecting vice-governors and other high-ranking positions from members of these powerful families was a way for regional governors to cement their authority and that of the emperor, whom they represented. In time, however, the loyalty of the vassal states and their leaders manifested itself, not as loyalty to the emperor and court, who ruled far away in Kyoto, but as loyalty to regional governors and the powerful families. Successive emperors had ruled poorly and generally ignored those outside the capital. This increased the standing of local leaders in the eyes of the people.

By the mid-twelfth century, members of local warrior clans began to rival civilian and court-appointed landowners of large shōen estates and emerged as leaders of the landowning class by binding their followers to themselves as vassals, rather than to the emperor and court. The influence of local leaders grew until in 1156 a group of military clan leaders settled a dispute over the succession to the throne. This incident, known as the Hogen rebellion, marked a turning point at which the warrior class stopped being subordinate to the court. For decades after the rebellion, the powerful military clans would battle for supremacy and influence amongst themselves.

In 1192, Minamoto no Yoritomo (1147–1199), a member of the powerful Minamoto clan, was awarded the highest military rank in Japan, Sei-i Taishōgun (征夷大将軍 – Commander-in-chief of the expeditionary force against the barbarians). Traditionally a temporary rank which ended at the completion of a military campaign, Yoritomo established the position as a hereditary system, passing the title on to his elder son Yoriie and then his younger son after that. While there had been shoguns before Yoshitomo, none had held more power or influence. So powerful was the Shogun that, while the emperor and court remained in Kyoto, they held a ceremonial position with little administrative power. Yoshitomo, however, with his new title and military government (bafuku – 幕府 – Tent Government) based in Kamakura, held military and administrative control of the country. So began the Kamakura Shogunate and the era of the shoguns in Japan, which would persist for the next 700 years.

Activities

- Japan is an island nation. Have the students define what an island is (as opposed to a continent) and compile a list of other island nations around the world. Have the students evaluate the strategic and economic advantages and disadvantages of being an island nation.

- Ask the students to consider how, as the emperor in a time where communication and travel were slower compared to today, they would minimise the risk of discontent among the population a long way from the capital? Ask them to create a plan to govern effectively, reminding them of the perils of absolute leniency and absolute violence.