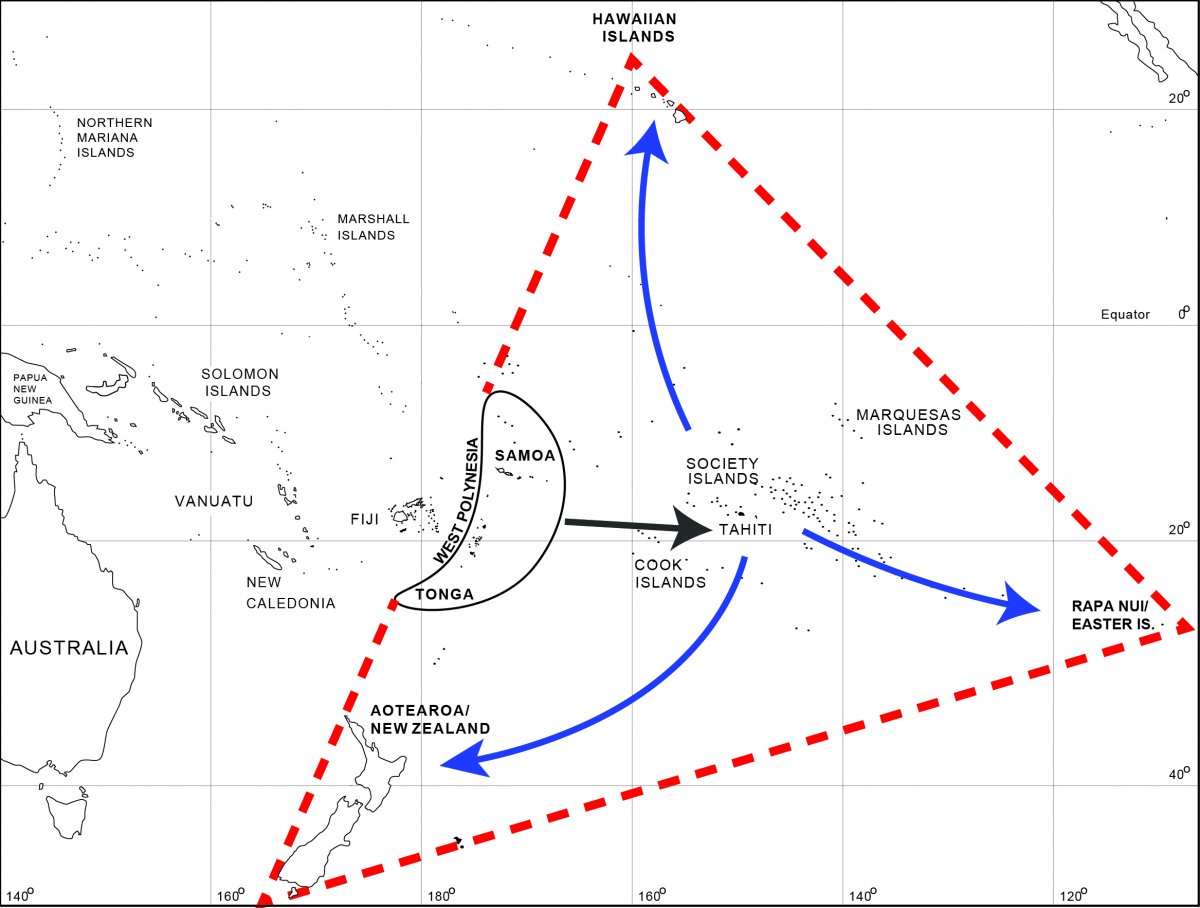

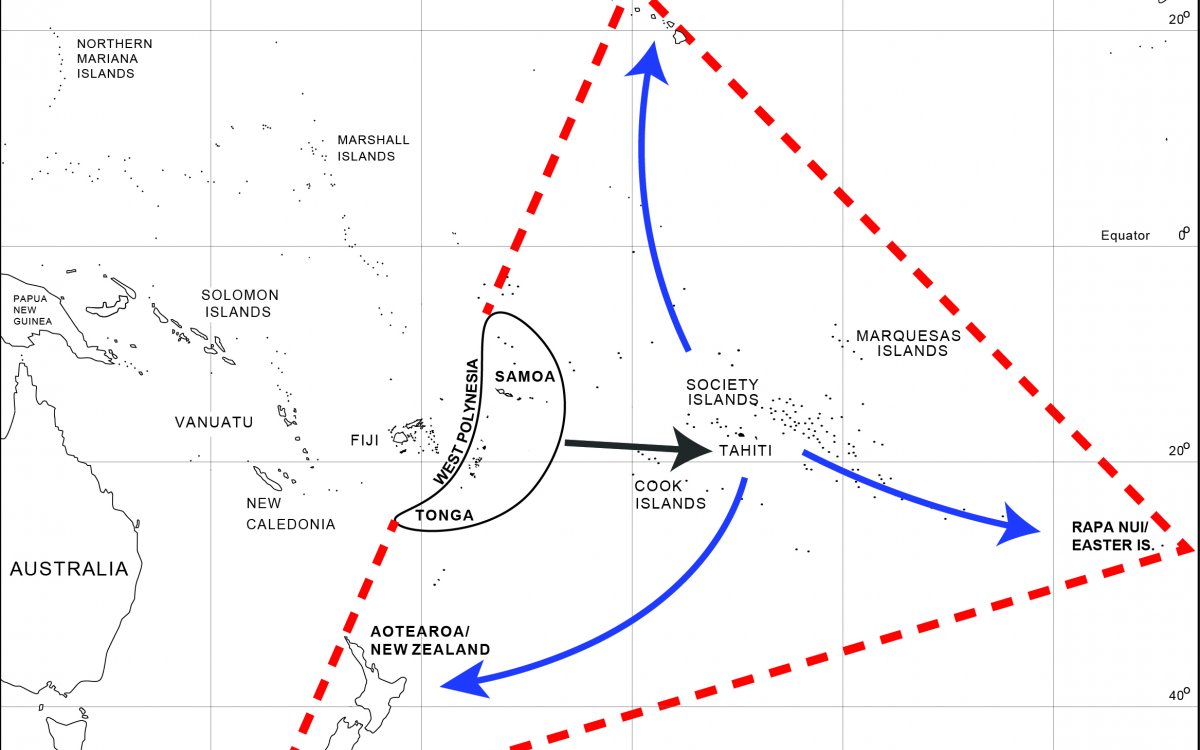

The three points of the Polynesian Triangle

When European explorers began to enter the Pacific they were astounded by its vast extent and fact that most of the islands were already inhabited. How long ago the scattered islands of Oceania had been occupied and by whom has therefore been an enduring question. This is especially the case in the east Pacific where the majority of remote islands—landmasses that are 350 kilometres or more from another island—are found. To navigators such as Captain James Cook, it was incredible that people in Tonga and Samoa spoke a language that was related to the languages used on islands thousands of kilometres away, in Rapa Nui (Easter Island), Aotearoa (New Zealand) and the Hawaiian Islands. The language similarity was unexpected, as it pointed to an ancient maritime migration covering more ocean than any other known to history.

| Language | "One" | "Two" | "Three" |

|---|---|---|---|

| Tonga | taha | ua | tolu |

| Samoa | tasi | lua | tolu |

| Aotearoa | tahi | rua | toru |

| Rapa Nui | tahi | rua | toru |

| Hawaiian Islands | kahi | lua | kolu |

The region containing the shared language became known as 'Polynesia', a term popularised by the French explorer Dumont d’Urville in 1832. It was later subdivided into West Polynesia—Tonga, Samoa and ’Uvea mo Futuna (Wallis and Futuna islands)—and East Polynesia, containing all of the islands within the three archipelagos of the Hawaiian Islands–Rapa Nui–Aotearoa that outline Triangle Polynesia (Figure 1). The corners of Triangle Polynesia are separated by 6000 to 7000 kilometres of ocean, similar to the distance from Brisbane to Tokyo. East Polynesia covers 36 million square kilometres of ocean, but within it the total amount of land is only 310,000 square kilometres, or less than one per cent of the total area. As Aotearoa comprises over 85 per cent of all land in East Polynesia, successful colonisation required remarkable canoe voyages, by people who were able to locate and settle small islands in a vast and mostly empty ocean.

Clark, G. (2021). Map of the Pacific showing Triangle Polynesia and colonisation movements from West Polynesia to East Polynesia [Map].

Beginnings of exploration

The beginnings of Polynesian expansion lie in West Polynesia, which was settled 2860 years ago during an earlier phase of oceanic expansion by pottery-making people of the Lapita culture. These people originated in the islands of South East Asia and migrated to islands around New Guinea before moving east into the Pacific as far as Tonga and Samoa. Around a thousand years ago, powerful chiefdoms developed in West Polynesia that had hereditary titles; the status of leaders was displayed mainly through architecture. These complex societies maintained contact with one another using ocean-going canoes that were the property of chiefs, as they were expensive to construct and maintain. Competition and conflict among these groups may have led to the discovery of islands in East Polynesia, but unplanned voyages are perhaps just as likely, given the amount of canoe travel in West Polynesia. Another possibility, seen in a study of lake sediments, is that an extended period of drought 900–1100 years ago led to social instability and voyages to find new lands to the east of Tonga and Samoa.

Whatever the reason, the discovery of new islands led to a rapid phase of migration that archaeologists have identified from the discovery of early sites in the Cook Islands, Society Islands and Marquesas Islands. Radiocarbon dating—a scientific method that measures the age-related number of carbon atoms in a sample—shows that wood charcoal from human fires in these island groups dates to 1000–1100 years ago. A second phase of movement, 700–800 years ago, then spread to the Hawaiian Islands, Rapa Nui and Aotearoa, which were harder to reach because of their remote position, small size and location in weather zones that were difficult to sail to due to prevailing winds and currents.

In the oral history of Polynesia, these epic colonisation journeys were recorded in tales of ancestral voyages and famous captain chiefs such as Kupe (Aotearoa), Hotu Matu'a (Rapa Nui) and Kaha'i (Hawaii) who navigated canoes and named newly discovered lands. The homeland of East Polynesian colonists in these traditions is known as ‘Hawaiki’: this might refer to the island of Savai'i (in Samoa) in West Polynesia or to locations in the Cook Islands or Society Islands where voyages to the outer margins of East Polynesia began.

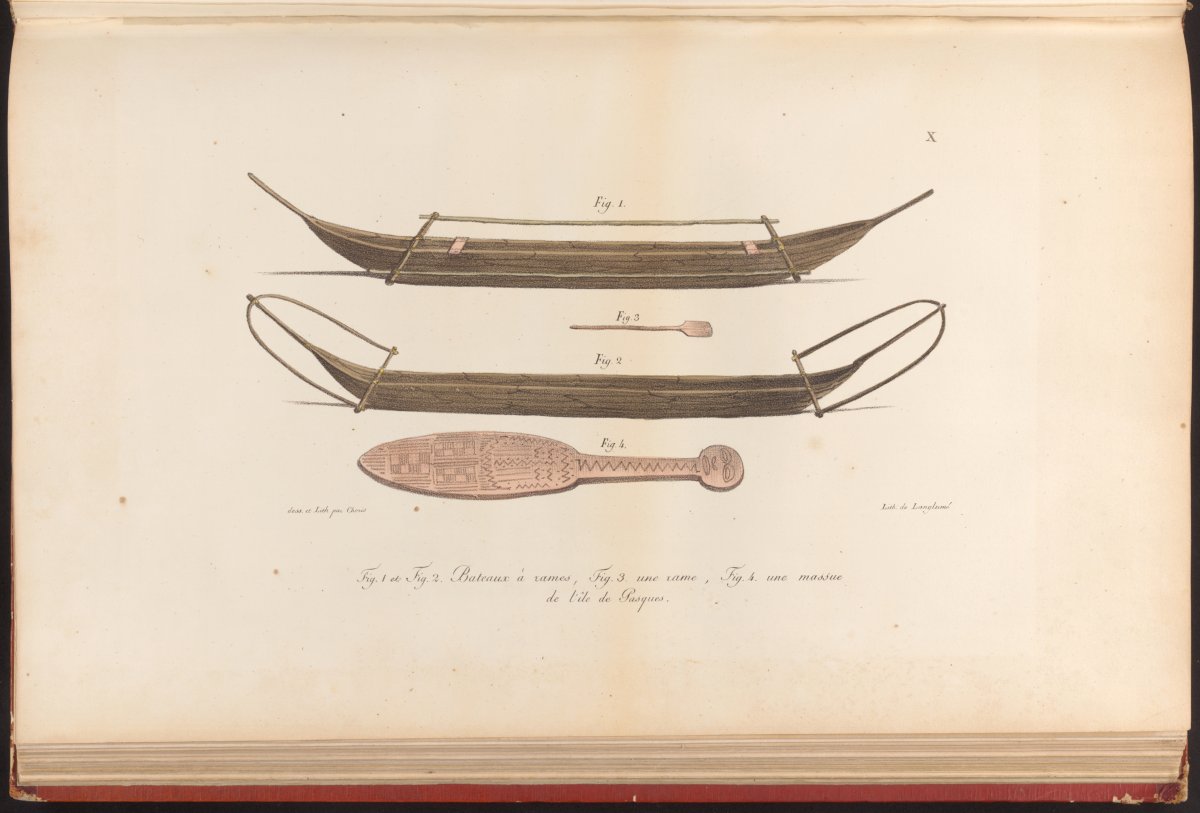

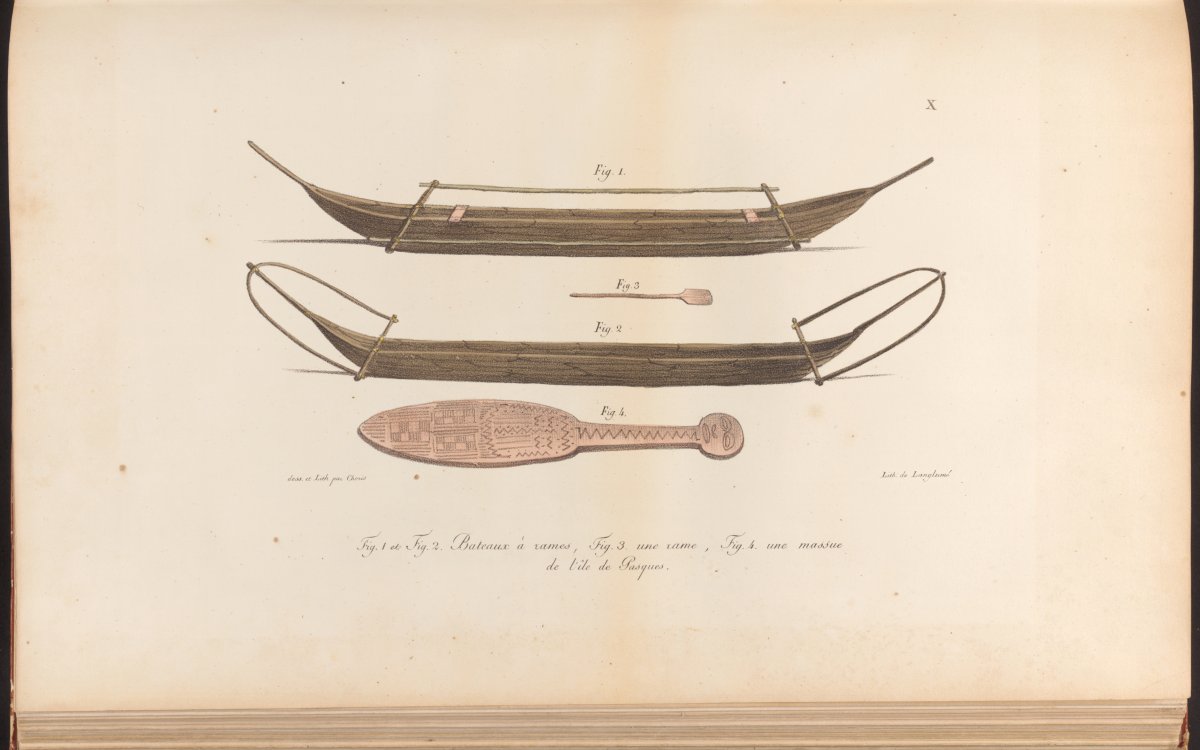

Choris, Louis, 1795-1828. Voyage pittoresque autour du monde & Choris, Louis, 1795-1828. (1822). [Canoes, and a club from Easter Island] [picture] / dess. et lith. par Choris. http://nla.gov.au/nla.obj-136165362

Polynesian expansion was achieved with canoes that were probably formed by joining two wooden hulls together and the vessel was propelled by a simple sailing rig. No remains of early voyaging canoes have been found, but the rapid discovery and occupation of East Polynesia suggests that founding populations were established relatively quickly by small canoe fleets or by multiple voyages from the Hawaiki homeland. Navigation was based on the sun during the day, the position of stars at night, and from the prevailing wind direction. These techniques are still used today in modern canoe voyages undertaken by Polynesians following ancient sea lanes.

Cultural and environmental divergence

Early Polynesian settlers initially shared a common language and culture that included a social organisation ruled by chiefs; belief in a pantheon of gods including Maui; the use of built sites for ritual activity; tattooing to mark the status and achievements of an individual; and a flexible fishing–farming–hunting way of life. The distant societies of East Polynesia began to diverge from one another soon after they were established, as the islands and environments they inhabited were very different from one other, and each colonising group brought with it only part of the cultural and genetic variation of the parent Hawaiki population.

For instance, Aotearoa is by far the largest landmass in East Polynesia, but is also considerably colder than tropical Polynesia. Foods such as taro, yam and sweet potato were difficult to grow in cooler parts of Aotearoa, while the important coconut palm was never established. Similarly, only some of the domestic animals that people depended on in West Polynesia were able to survive the long and arduous canoe voyages to East Polynesia. In the tropical Hawaiian Islands the pig (Sus scrofa), dog (Canis familiaris), chicken (Gallus gallus) and Pacific rat (Rattus exulans) were all introduced, but only the dog and Pacific rat made it to Aotearoa, and the chicken and Pacific rat to Rapa Nui. A good example of cultural differentiation is the development of distinctive ritual sites in East Polynesia. The huge stone statues of Rapa Nui known as moai contrast with the stone temples of the Hawaiian Islands (heiau), and the chiefly ceremonial areas (marae) of the Society Islands revealing that new religious and political structures were emerging from ancestral Polynesian forms.

Further exploration

After reaching the limits of the Polynesian triangle, navigators might have ceased their expansion as they realised there could only be a small amount of land left to find, or that long voyages were difficult due to the inevitable loss of life involved in oceanic exploration. Yet, surprisingly, evidence suggests that Polynesian sailing extended to both sides of the Pacific Ocean.

Bottiglia, C. (1820). [Inhabitants and monuments of Easter Island] [picture] / C. Bottiglia f. http://nla.gov.au/nla.obj-135963198

It has long been known that Polynesians had contact with the Americas, as several food plants such as the sweet potato (kumara) that is grown in Polynesia came from South America. A recent genetic study shows that Polynesians in Rapa Nui and the Marquesas had been in contact with people from Colombia–Ecuador, probably from canoe passages that reached the South American coast. On the other side of the Pacific Ocean, archaeologists discovered an abandoned Polynesian site on Norfolk Island—an external territory of Australia—and Polynesian stone tools have been found on the east coast of Australia. Polynesians also sailed southward to islands in subantarctic latitudes (50° South), and Polynesian communities settled on small islands to the west of Tonga–Samoa in Melanesia and Micronesia.

Migration is an integral part of society that, in the case of Polynesian peoples, developed into a culture of mobility based on voyaging in large sailing canoes. The maritime technology was combined with a belief that the Pacific Ocean was not infinite and that new lands lay beyond the horizon for those ready to risk the journey.

Activities

- Innovative scientific processes, such as radiocarbon dating have helped anthropologists to identify and more accurately date evidence of the migration and settlement of people across Polynesia.

- Have students research and discuss the science behind radiocarbon dating. They might like to think about what radiocarbon dating can tell us about the past and what other applications it might be useful for.

- Have students research and discuss the science behind radiocarbon dating. They might like to think about what radiocarbon dating can tell us about the past and what other applications it might be useful for.

- Have students research the commonality of the food staples, such as taro/kalo, pigs, coconuts etc found across many of the Polynesian and wider Pacific nations. How have these staple foods been adapted across different locations.Compare recipes from different Polynesian nations that use one of the staple foods. Are there any other similarities or differences between the recipes? Are the farming practices different across the Polynesia region due to different environments. Do any Polynesian nations have a unique staple food?

- Have students study the design and elements of a Polynesian canoe. Ask them to design and make their own canoe out of basic crafting supplies. The canoes should use the elements featured in Polynesian craft including sails and outriggers. Students can compete in teams to race or sail their canoes or just display them. Further building activities could including building more canoes without features like outriggers and comparing how stable the crafts are in (simulated) rough seas, or how hydrodynamic the craft is without its sleek profile etc. What advantages did this innovations give to early mariners navigating the vast expanses of the Pacific Ocean?

|

Image

|

Professor Geoffrey Clark is an archaeologist at the Australian National University who has worked on islands in the Indian Ocean and the Pacific Ocean. His interests focus on maritime migration and island colonisation, the development of early states and the impact of warfare in the past. |