A view from Tahiti and the Society Islands

Many European explorers, sailing across the eastern Pacific islands from the eighteenth century onwards, reported with astonishment their visits at religious sites, the impressive carved statues and the complex ceremonies they witnessed. Open-air temples built of stone and coral were known as marae in the Cook Islands, Tahiti, the Tuamotu Islands and Aotearoa, me’ae in the Marquesas Islands, heiau in Hawaii, and ahu moai on Rapa Nui. Tongan mala’e and Samoan malae also refer to ceremonial plazas. Despite linguistic and architectural variations across the region, all of these sites pertain to the pan-Polynesian marae concept: a sacred (tapu) place of interactions between the ao, the world of the living, and the pō, the world of deities and ancestors. Nowadays, thousands of marae ruins are scattered in the island valleys and attest to their prominence in ancient chiefdoms.

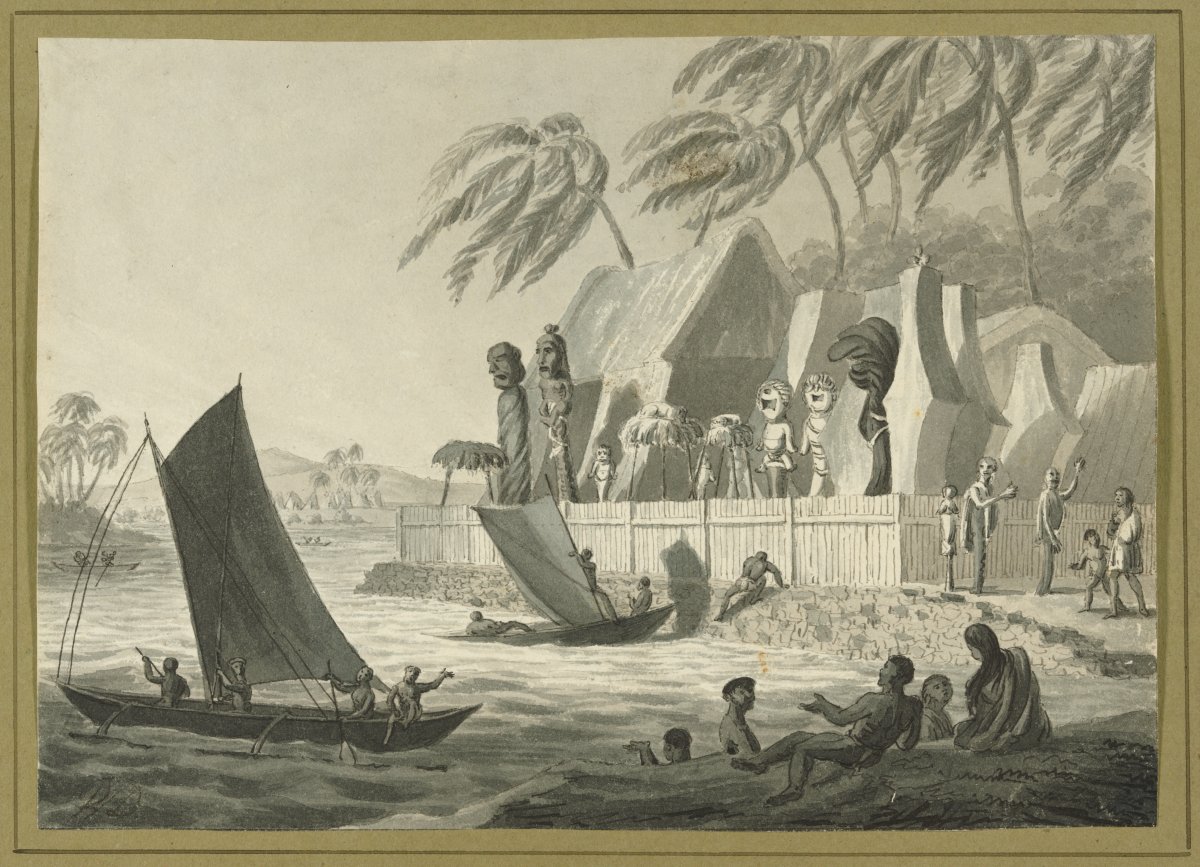

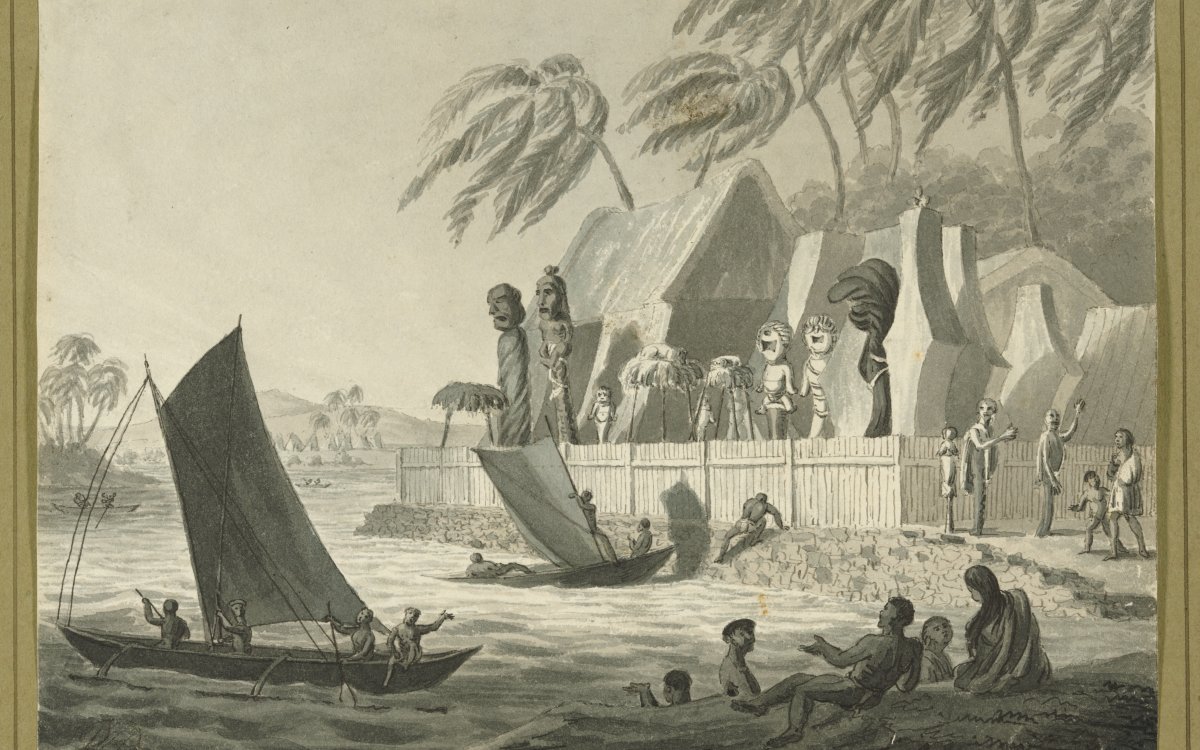

Choris, Louis, 1795-1828. (1825). [Morai near Karakakooa, Sandwich Islands] [picture] / R.D. http://nla.gov.au/nla.obj-135577085

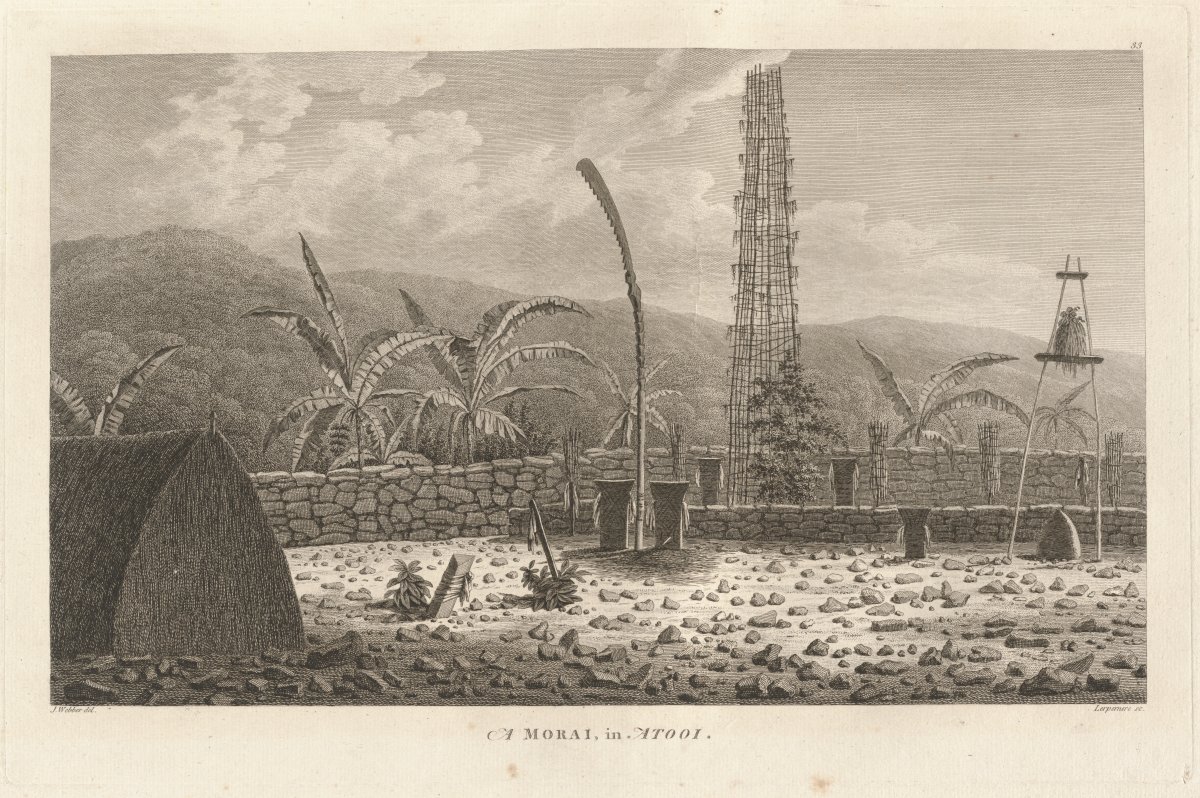

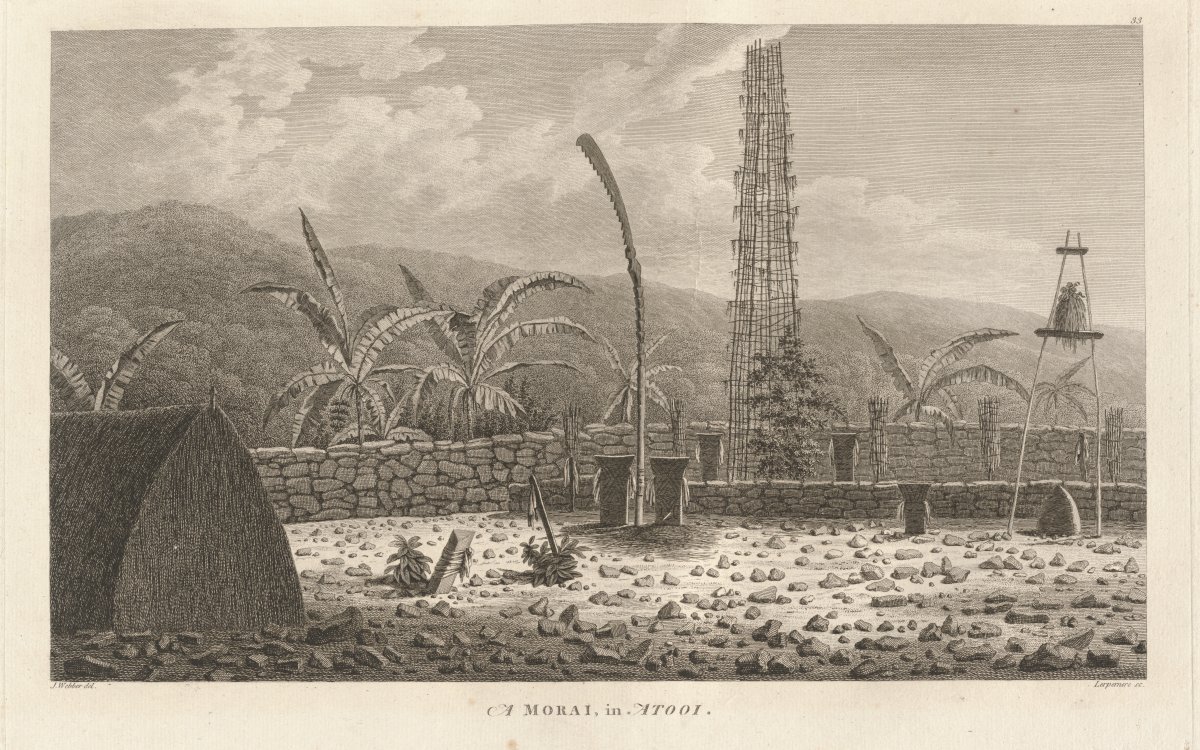

Lerpiniere, Daniel, 1745-1785 & Cook, James, 1728-1779. Voyage to the Pacific Ocean & Webber, John, 1752-1793. (1784). A morai in Atooi [picture] / J. Webber del.; Lerpernere [sic] sc. http://nla.gov.au/nla.obj-625227838

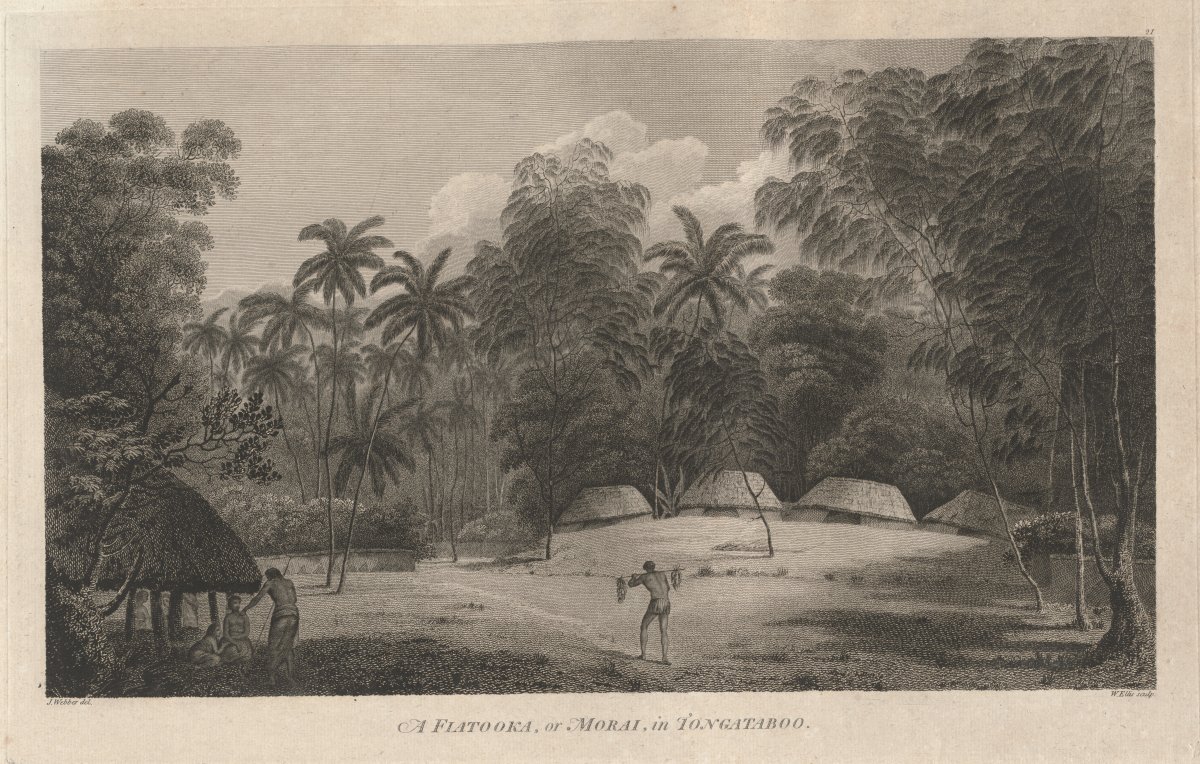

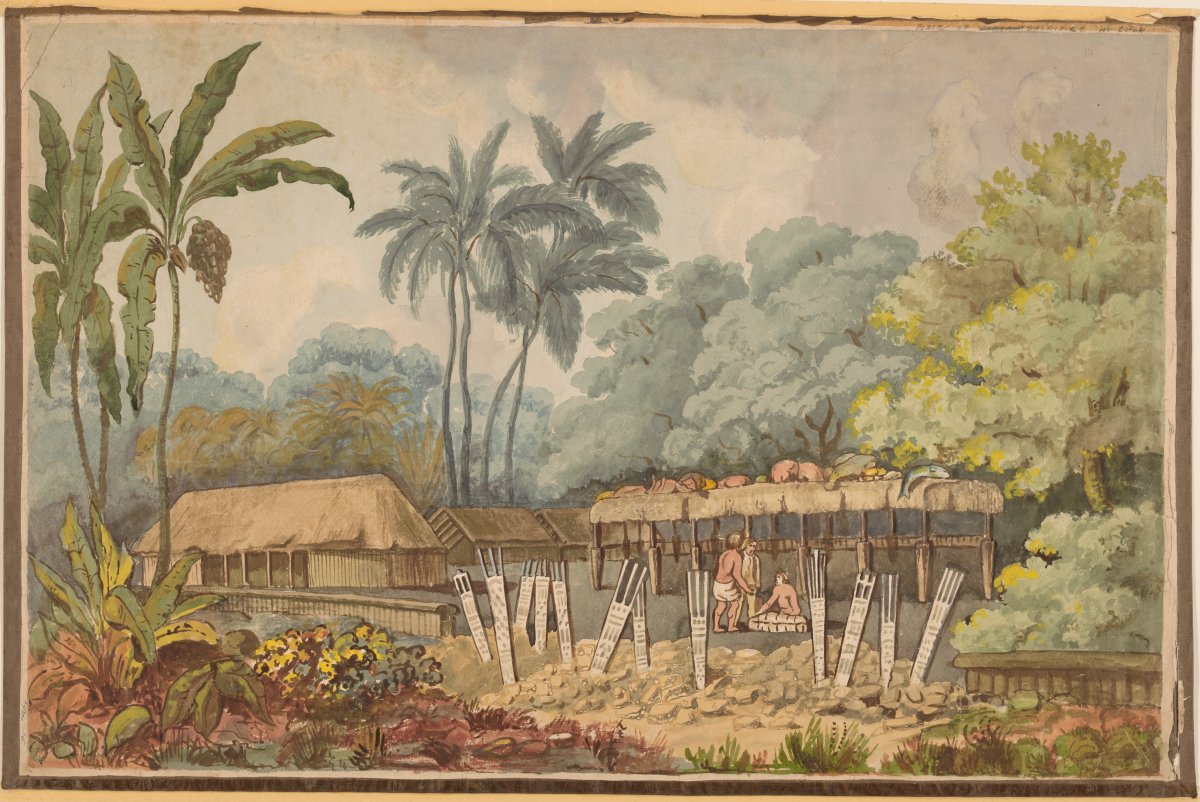

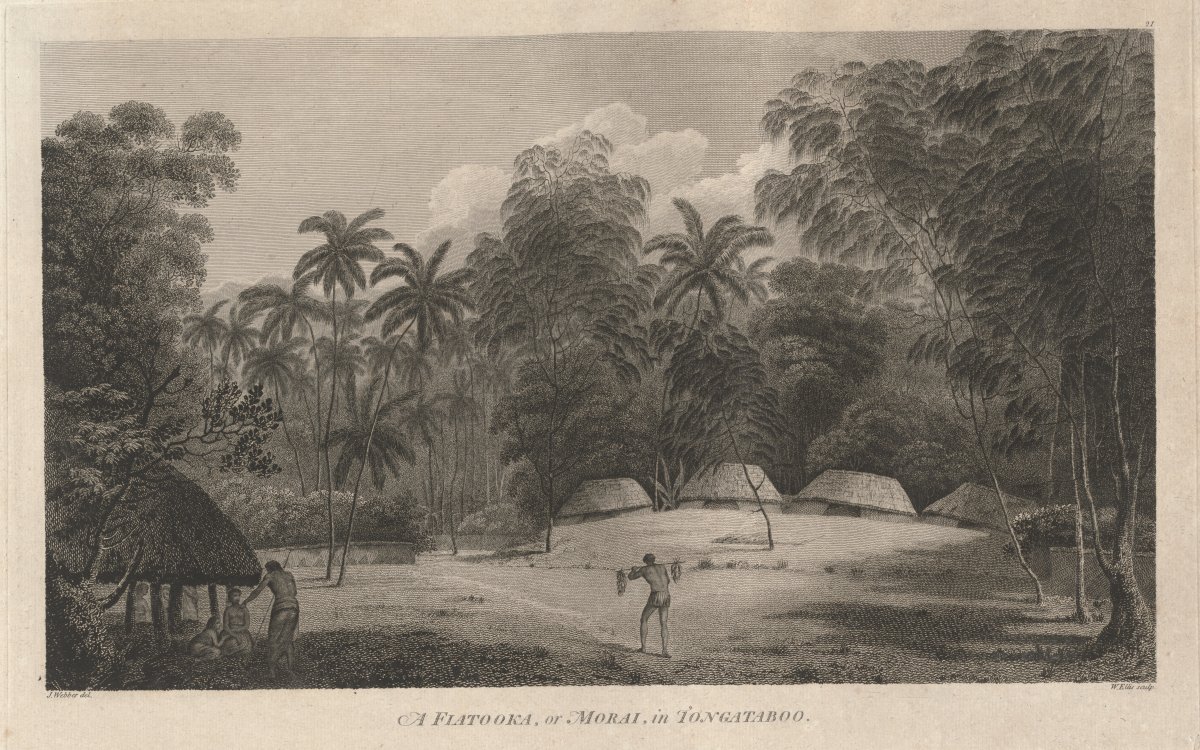

Ellis, William, 1747-1810 & Cook, James, 1728-1779. Voyage to the Pacific Ocean & Webber, John, 1752-1793. (1784). A fiatooka, or morai, in Tongatabo [picture] / J. Webber del.; W. Ellis sculp. http://nla.gov.au/nla.obj-625223511

The elements of a Tahitian marae

In the Society Islands, of which Tahiti is the largest, marae were ceremonial places organised around a central court that could be enclosed by low walls. At one end of the court, the ahu comprises a platform-like structure made of stone and/or coral slabs, similar to an altar. The largest marae built in Tahiti, the marae Maha’iatea, displayed an 80 metre–long pyramidal ahu of ten degrees. Erected on top of the ahu, upright stones, sometimes human shaped, served as the repository for the spirits of the gods and ancestors invoked during the rituals. The priests deposited plates of food offerings in front of these sacred stones and ornamented them with garlands of flowers and shells. In the rest of the court, other stone seats marked the position and rank of the officiants during the ceremonies.

While only stone features have stood the test of time, the marae also included special constructions made of perishable material. Aside from the priest’s house, the sacred objects, such as plates, drums and to’o figures (representations of the gods and ancestors), were stored in the fare ia manaha. Offerings of bananas, roasted pigs and fish were placed on top of wooden platforms with posts were shaped in a conical form to prevent rats from climbing them and touching the sacred food reserved for the deities. The unu were wooden boards carved with animal motifs symbolising the identity of the social group.

The rituals conducted at the marae

In ancient times, occasions for conducting rituals at the marae were numerous; however, the Christianisation of the populations by the Catholic and Protestant missionaries in the nineteenth century led to the prohibition of these ‘pagan’ practices and the abandonment, and even destruction, of the marae. Thankfully, oral traditions provide us with a better understanding of ceremonial activities that occurred at all levels of the chiefdoms, from the family group to the whole community and chiefs.

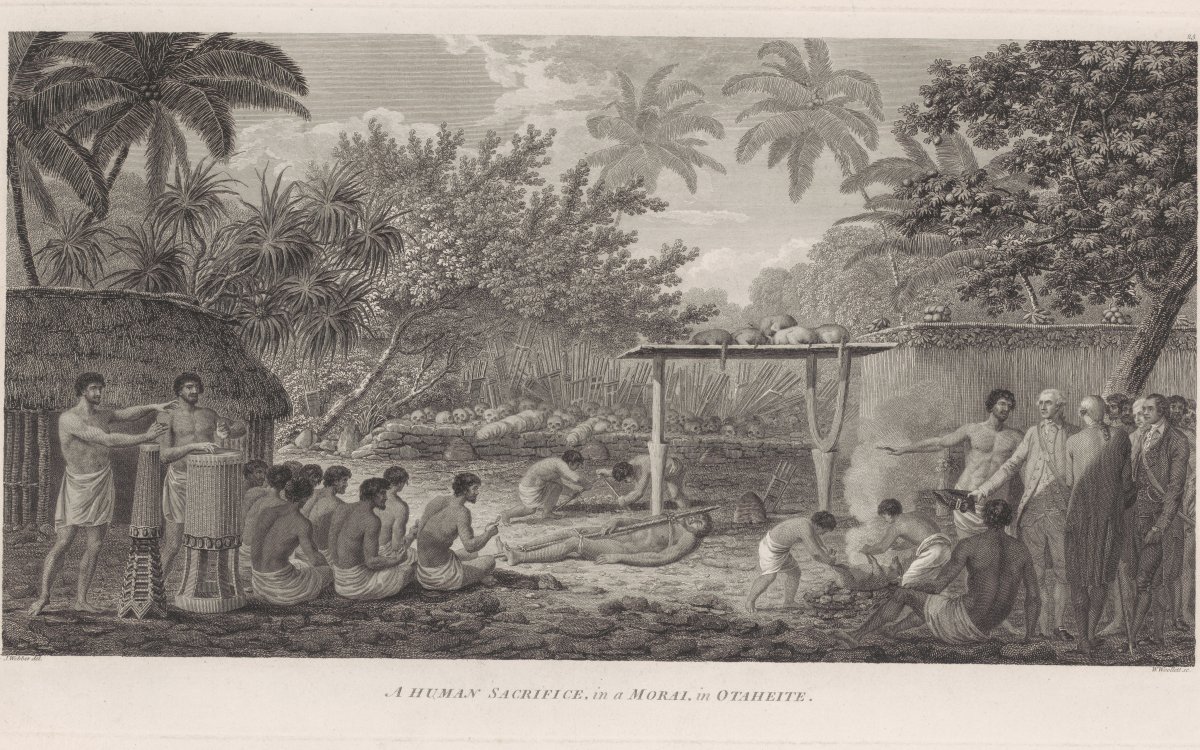

Many rituals were linked to fertility renewal, and people commonly recited prayers asking the gods some favour: for a good fishing party, or a productive harvest. The rise of the Pleiades constellation in the sky, called matari’i i ni’a, marked the beginning of the abundance season in the traditional calendar and was celebrated at the chief’s marae. In the Tuamotu Islands, people would capture the first turtles of the season, seen as a gift from the ancestors, and bring them to the marae where they were sacrificed, cooked in the ovens and consumed by the participants. Other ceremonies aimed at elating the warriors (to’a) before a battle, or calling a truce after a war. The specialists of various crafting activities (tau’a) also performed rituals linked to their professions. For instance, the canoe builders put their adzes ‘to sleep’ at the marae before starting a new construction, so the tools could acquire some mana and thus become more efficient.

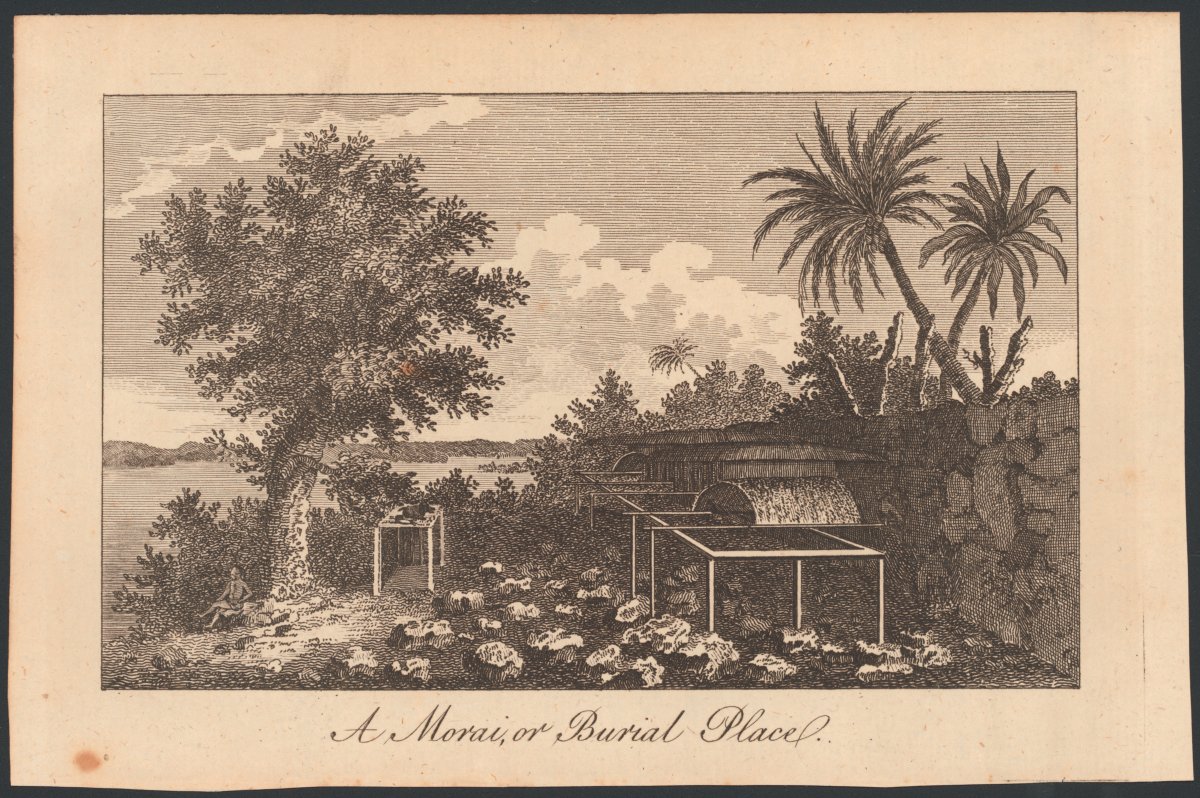

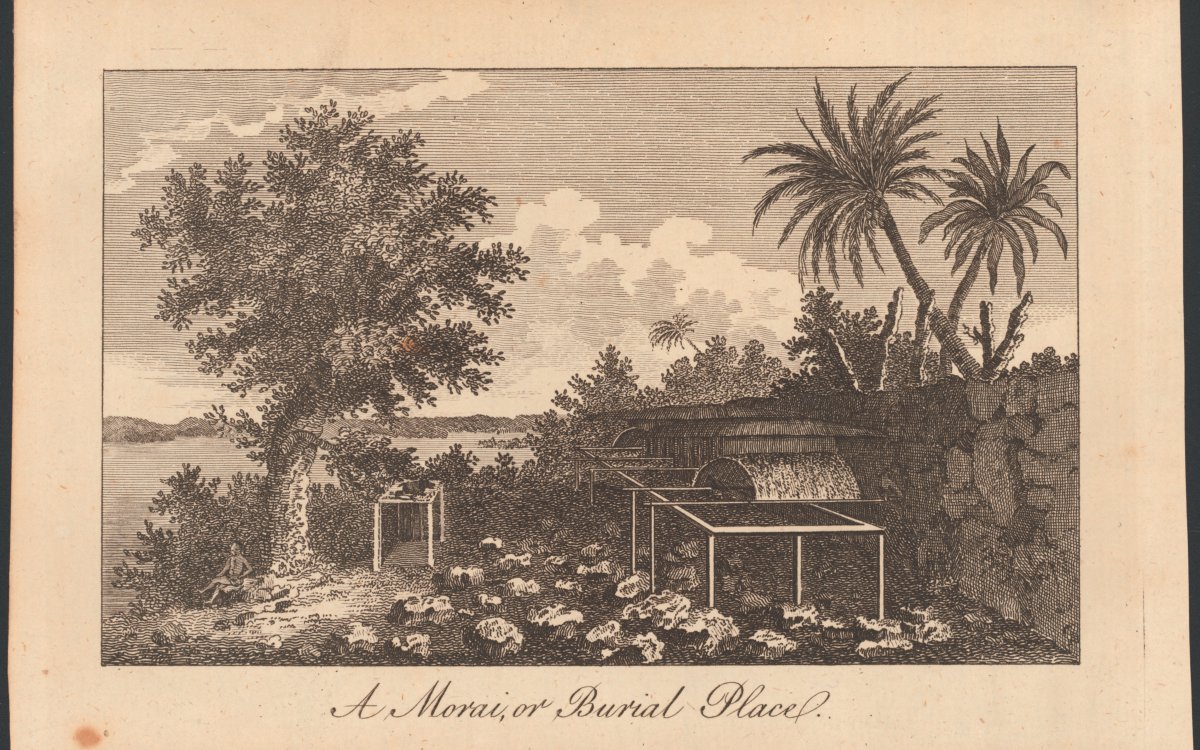

Marae and shrines were also dedicated to the cult of the ancestors. Some European drawings depict funerary platforms called fara tupapa’u where the bodies of the deceased chiefs or leaders were left exposed, sometimes for months. During this period, the Tahitian priests wore a mourning costume made of tapa (barkcloth) and hundreds of shining pearl shell pieces. Bones of the deceased were later picked up and concealed in some niches of the marae, or in rock shelters in the mountain. Families kept bringing offerings to the ancestors, while reciting their genealogies. The deified ancestors continued to play a role for the living and were memorialised in stone, as in the Marquesan tiki figures, as well as the moai statues on Rapa Nui.

Newton, James, 1748-approximately 1804 & Parkinson, Sydney, 1745?-1771. Journal of a voyage to the South Seas, in His Majesty's ship, the Endeavour. A morai, or burial place [in the Island of Yoolee-Etea] [picture]. http://nla.gov.au/nla.obj-136606240

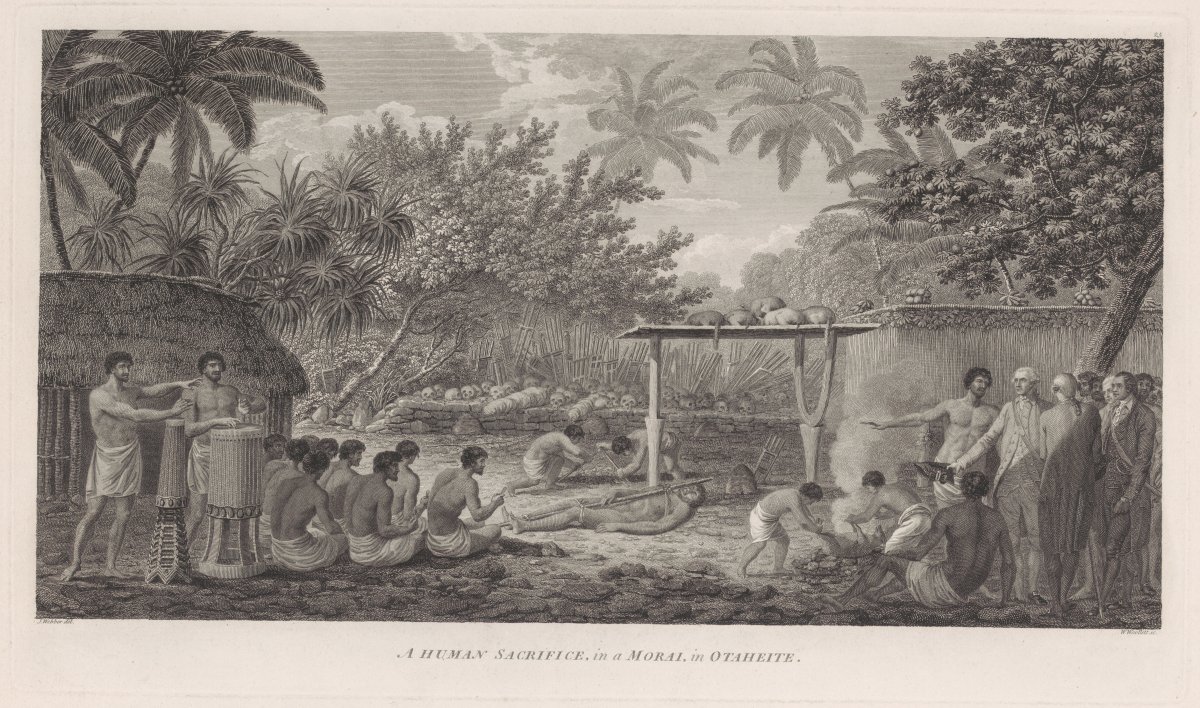

Woollett, William, 1735-1785 & Webber, John, 1752-1793 & Cook, James, 1728-1779. Voyage to the Pacific Ocean. (1784). A human sacrifice in a morai in Otaheite [picture] / J. Webber del.; W. Woollett sc. http://nla.gov.au/nla.obj-135724101

Williams, John, 1796-1839 & Webber, John, 1752-1793 & Cook, James, 1728-1779. Voyage to the Pacific Ocean. A human sacrifice in a morai in Otaheite [picture]. http://nla.gov.au/nla.obj-136423378

The marae as places of socio-political power

The most impressive monuments belonged to the chiefs, the ari’i nui. The labour-intensive constructions further reflected the chiefs’ sociopolitical power and authority. On the island of Raiatea, the Tamatoa dynasty of ruling chiefs founded its centre at the Taputapuātea complex. Navigators from distant islands came to meet with the ari’i at the main marae, dedicated to the god of war, ’Oro. The marae Hauviri, built by the lagoon shore, welcomed the lavish ceremonies held for the rise of a new chief. The latter sat back against the large white stone erected in the middle of the court and the priests presented him with the red-and-yellow feathered girdle, called maro ’ura, the most sacred insignia of the ari’i. During the festivities, the figure of the god ’Oro was taken out of his sacred container and displayed on the marae: these sacred figures (to’o) consisted of a piece of wood covered with sennit (a braided rope) and decorated with feathers, and served as the receptacles of the deities. Because of its importance for Polynesian people, the Taputapuātea site was recently listed as a UNESCO World Heritage site.

Webber, John, 1752-1793. Views in the South Seas. (1789). A toopapaoo of a chief, with a priest making his offering to the morai in Huoheine [picture] / J. Webber fecit. http://nla.gov.au/nla.obj-135726448

Webber, John, 1752-1793. Views in the South Seas. (1789). Waheiadooa, chief of Oheitepeha, lying in state [picture] / J. Webber fecit. http://nla.gov.au/nla.obj-135725616

Marae were thus more than just ceremonial sites. Their hierarchy mirrored the social organisation of the chiefdom, from the small family shrines to the large temples that cemented political alliances. Marae further represented the connection of a group to their ancestral lands, the history of their clan: in other words, their identity.

The restoration of many marae sites, conducted by archaeologists and cultural bodies, contributed to the Polynesian renaissance in the 1970s. Marae embody Polynesian origins, histories and traditional connections, and they are progressively reinvested as places of sharing and celebrations of the Polynesian identity and living culture.

Activities

- Various types of materials in Polynesian societies were thought to have a symbolic connection to the gods and ancestors. Seeking out symbolic treasures often involved treacherous journeys over coral reefs and at times resulted in war against rival villages. The tusk of the boar represented fierceness and strength and was worn by warriors. Human hair from ancestors was woven and plaited into many items to give strength to family bonds.

- Ask students to research a traditional ceremony from a the Polynesian region. What are the features of the ceremony? Are there special materials worn? Are there any ceremonial objects that are used? What symbols are featured during the ceremony or in ceremonial spaces?

- Many Polynesian and Pacific societies are known for their body markings. The symbols and patterns used in traditional tattooing carried many means. Traditionally, bone chisels with sharp points were dipped into pigment and then tapped into the skin with a miniature mallet. Detailed geometric patterning covered much of the body and face in Samoa and revolved around the ritual of adolescence to manhood. Markings on women more generally focused on one section of the body, an example of this can be seen in Māori tradition where women carry tattoos around their mouth.

- Have students investigate the meanings of symbols and patterns that feature in traditional Polynesian and Pacific Islander tattoos. Who can have one? Are there some patterns or symbols that only men or women can have? Is there a condition that must be met to be allowed to get a particular tattoo? What does it mean to have a tattoo? Do other nations/cultures have similar patterns and symbols?

- Have students consider the permanence of a tattoo and the significance of the decision to get one. What does it mean to carry a mark for, the most part, life?

|

Image

|

Guillaume Molle is a Senior Lecturer in Pacific Archaeology and Australian Research Council DECRA Fellow at the Australian National University, and Deputy-Director of the International Centre for Polynesian Archaeological Research (CIRAP), Tahiti. His doctoral thesis at the University of French Polynesia (2007-2011) was a study of the pre-contact past on the island of Ua Huka (Marquesas). He is particularly interested in human settlement in the Pacific and is developing an archaeological approach to ritual in order to document more fully the ancient Polynesian religious systems. He has led or co-led several research missions in the Marquesas Islands, the Gambier and Tuamotu Archipelagos and on the atoll of Teti’aroa. He has published a number of scholarly articles and monographs and is currently preparing a work on the archaeological history of the Marquesas Islands to be published by the University of Hawai’i Press. |