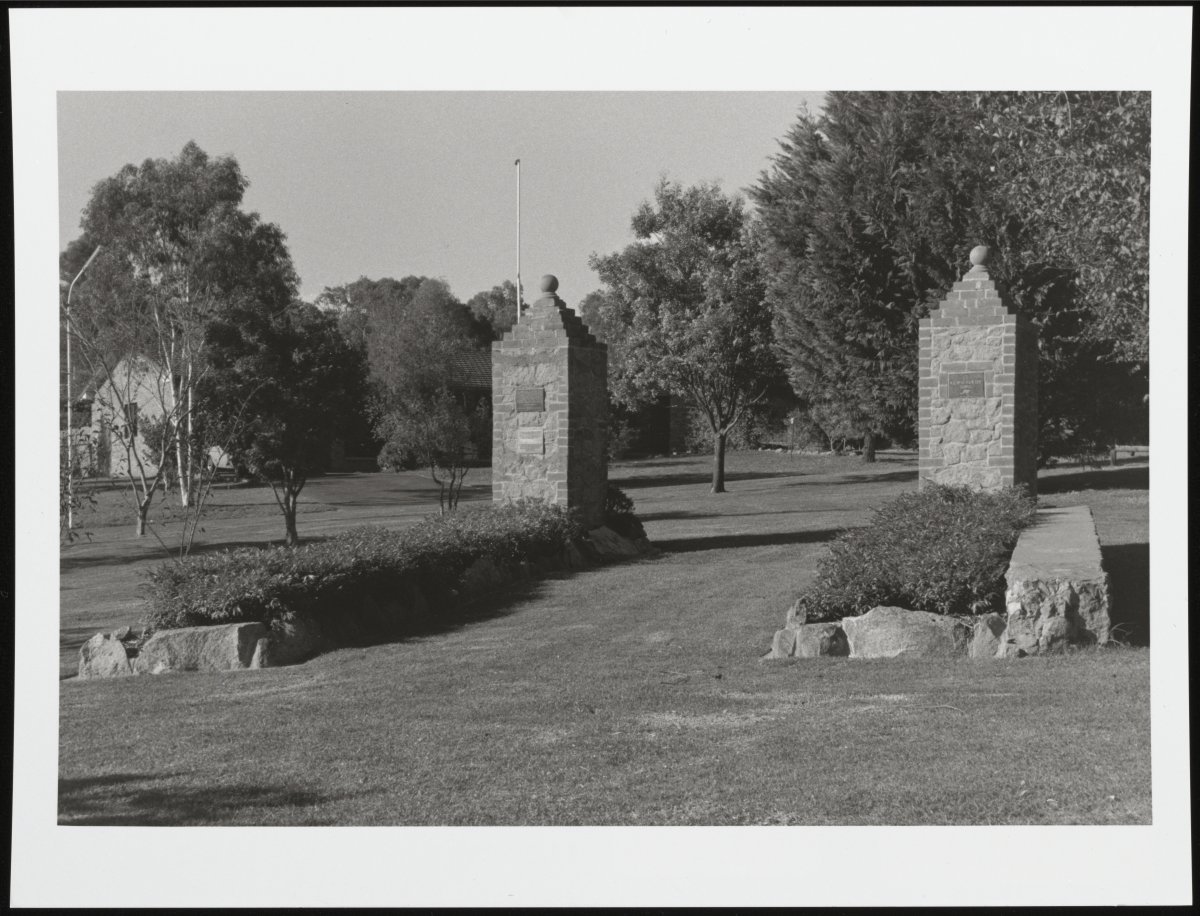

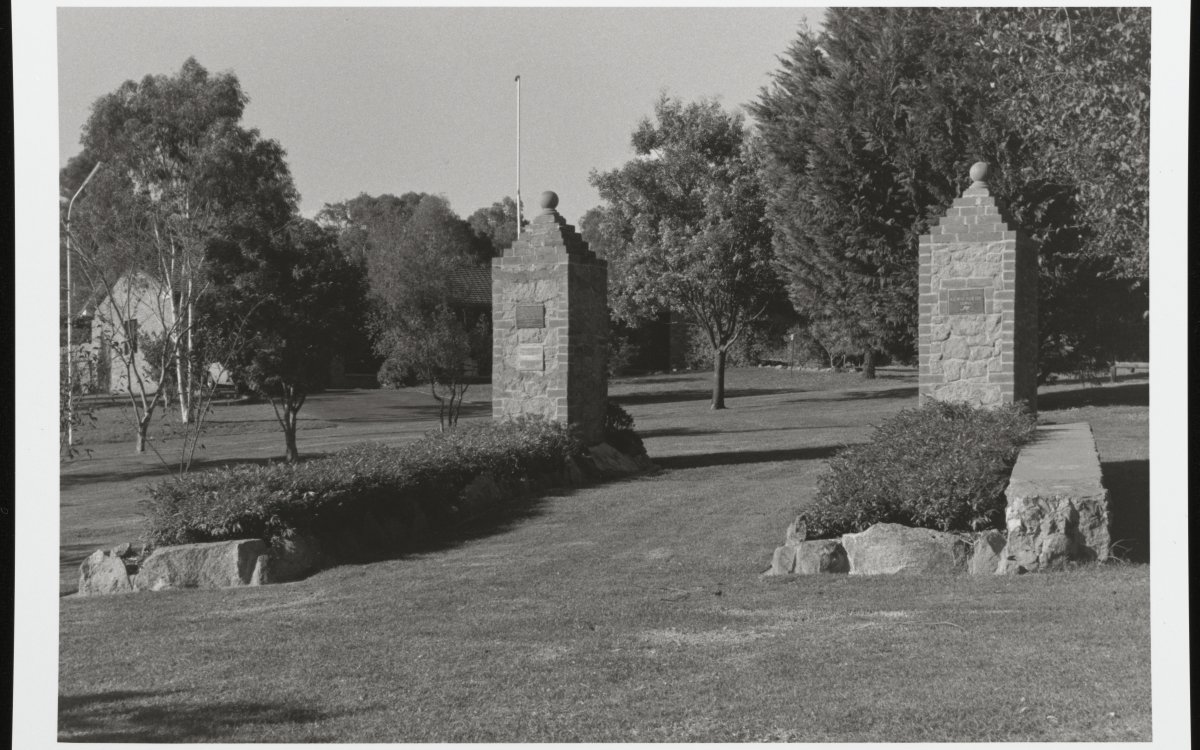

Kelson, Brendon, 1935-2022. (1996). Garrison Gates Memorial (former entrance to POW camp), Binni Creek Road, Cowra [picture]. http://nla.gov.au/nla.obj-143115748

Cowra Prisoner of War Camp

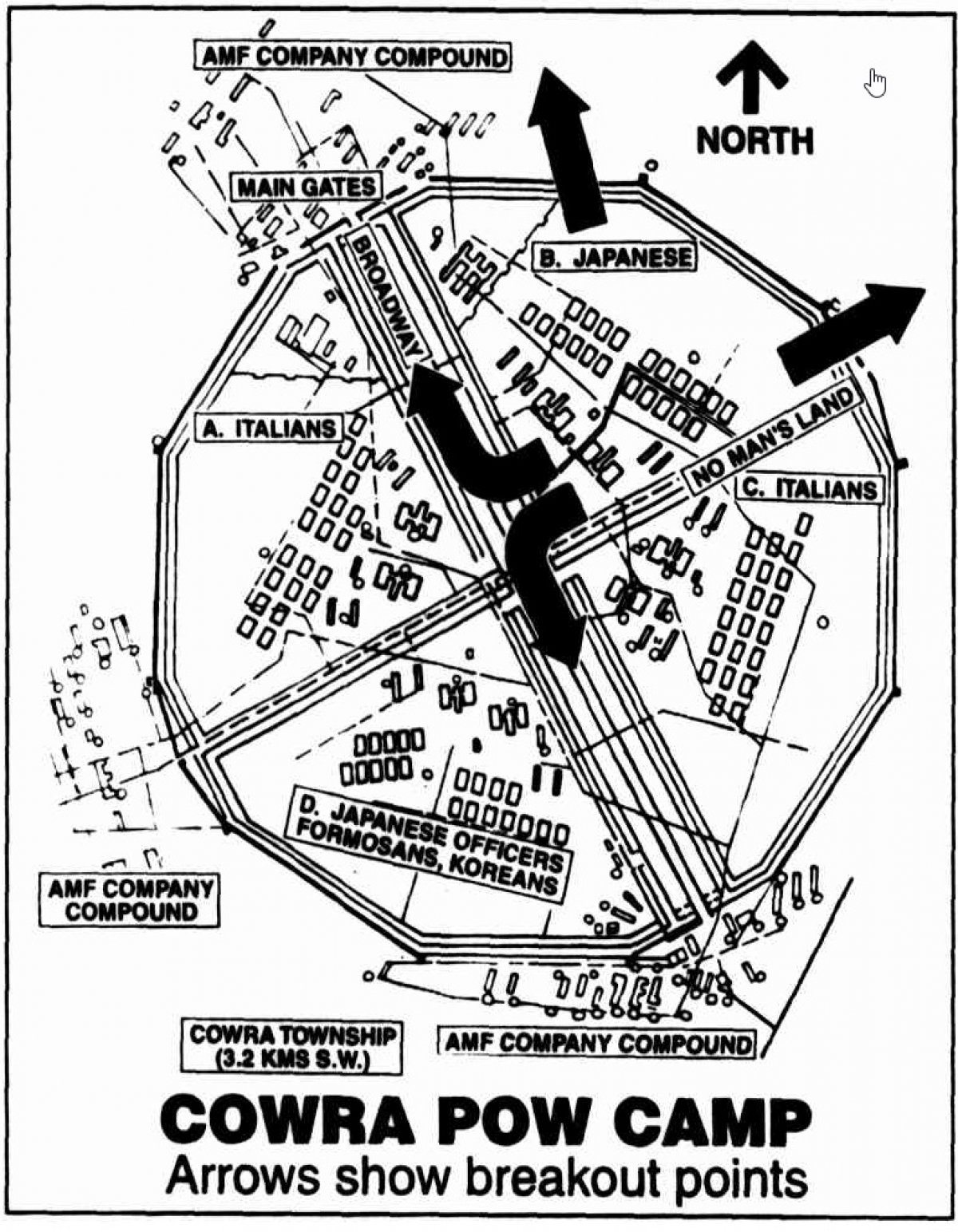

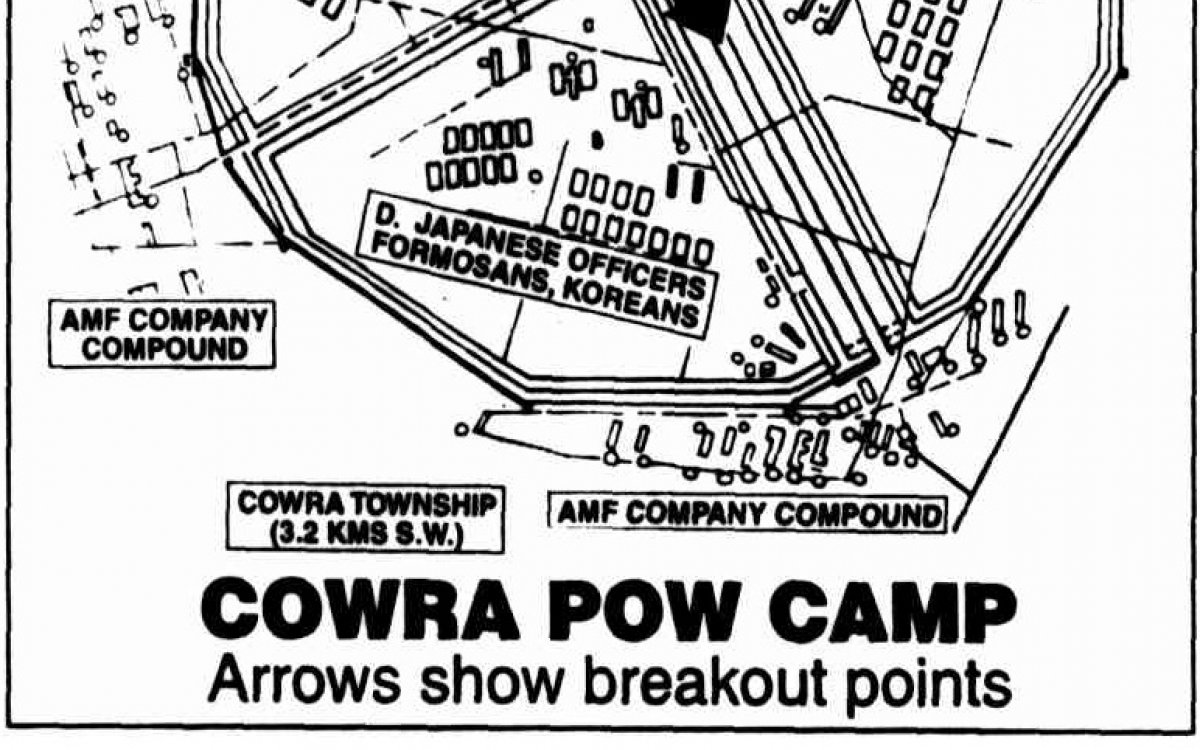

Opened in 1941, the Cowra camp was used as a site to house the growing number of Prisoners of War (POWs) from the Mediterranean theatre of war, mainly Italian and German troops. Following a design similar to other POW camps, Cowra had a perimeter fence enclosing an area of roughly 28 hectares, divided into four equal-sized compounds by two intersecting roads. Each road was about 700 metres long and one of them was wide enough to carry vehicles. This was known as Broadway. At each end, there was a gate. Movement within the camp was difficult, but escape was an even trickier affair. Each compound was divided from the others by wire fences and barbed wire.

Although best known as a prisoner-of-war camp, the Cowra site was also used to house civilian internees. Located in the central west of New South Wales, it helped to meet a growing demand for space for civilian internee accommodation. Some local Italians spent time in a compound there, as did nearly 500 Indonesians.

Cowra is widely known as part of Australian wartime history for being the site of the largest prison breakout of World War II, and the bloodiest.

Unrest

In August 1944, the efforts of Japanese POWs to free themselves from the shame of imprisonment triggered a bloodbath that had long-lasting impacts on the survivors and their captors.

It soon became clear to Australians that Japanese attitudes to capture and imprisonment were quite different from those of Italians and Germans. The prevailing cultural attitudes of the Japanese soldiers dictated that to be captured and imprisoned brought great shame: shame on the prisoner, his family, Japan and the Emperor. Many Japanese soldiers avoided capture by taking their own lives. Those who were captured often did not give their true names and refused the opportunity to contact their families. Better, they thought, to let their families believe they had been killed in battle serving their country.

As the war continued, and Japan started to lose territory in the Pacific with the advance of the Australian and United States forces, the stream of Japanese POWs increased. By the middle of 1944, the Japanese compounds at Cowra were full. Along with Japanese military personnel, there were also around 500 merchant seamen, who were treated as POWs. All faced the prospect of eventually returning home to Japan, at the end of hostilities, with ambivalence, at best. For some men, the hope remained that captivity might present them with the opportunity to resume the battle against their enemies. To lose their lives in this way would at least remove the shame of being captured.

Eventually, the crowded conditions in Cowra saw the Australian authorities consider a transfer of about 700 prisoners to another camp at Hay, 400 kilometres to the south-west. When this plan was communicated to the POWs, it cause increased stress and anger among the men. Over many months, the men had built a community. They now faced separation and an uncertain future.

In B Compound, the Japanese began to plot a breakout. Lively discussions took place in the Japanese huts in the hours following the announcement of the transfer. While not all favoured dramatic action, the thought of a transfer had intensified the feelings of discontent into those of rebellion.

Most realised that the chance of staging a successful breakout was low. Even if they were to get clear of the camp, there was little hope that they would be able to make their way home. Cowra is 72 kilometres from the nearest large city and more than 300 kilometres from Sydney and the coast; however, even with the odds so low, they were undaunted.

After some debate, the men in most huts voted on a course of action. In one or two instances, the hut leaders did not permit a vote and ordered their men to take part in the revolt.

With a clear majority favouring rebellion, a time was set: the night of 5 August 1944. The agreed plan called for one group of prisoners to attack the Vickers machine gun at the northern corner of the camp, while another group would aim to breech a designated section of the perimeter fence. If successful, they would make their way to the nearby infantry training camp, taking the Australians there by surprise and avoiding any possibility that they would rush to defend the camp. A third group of prisoners would attempt to break into Broadway to deal with the guards who would be gathering to stop the uprising. Once in Broadway, one group would make their way into D Compound, where the Japanese officers were held.

FEATURES The night the sky was glowing red (1994, July 9). The Canberra Times (ACT : 1926 - 1995), p. 42. http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article118189979

The Breakout

A bugle call just before 2am signalled the beginning of the revolt. The group that forced its way into Broadway took the guards by surprise; a tower equipped with a Bren gun capable of cutting down the escapees was not manned. The speed and weight of the assault from the Japanese compound into Broadway forced open the gate. At the same time, and adding to the confusion, fires carefully lit in the Japanese huts began to consume not just the buildings, but the bodies of some 20 Japanese who had chosen to take their own lives.

The failure of the breakout can be attributed in large part to just two men, Ralph Jones and Ben Hardy, both of whom would be posthumously awarded the George Cross for their actions that night.

The two men realised that the outcome of the breakout would depend on which side gained control of the unmanned machine gun situated 50 metres outside the perimeter fence. It would be a race that pitted the two guards against more than 200 Japanese POWs.

The POWs brought with them blankets and coats to throw onto the barbed wire, and carried baseball bats and weapons made from whatever other materials they could find to stab or bash any resistance.

Hardy and Jones won the race and immediately began firing into the advancing Japanese. Some were killed, while others saw the futility of the situation and took their own lives, but enough cleared the third layer of fencing to take on the Vickers gun and the two men firing it. Hardy and Jones stood their ground and continued firing the gun; while doing so, they were clubbed and stabbed to death. The Japanese prisoners were unable to operate the gun and, aware that more guards would soon catch up to them, they fled the camp.

Fire raged within the compounds. The Australians set up positions at both ends of Broadway, from where they were able to fire into both B Compound and Broadway. Following their plan, some of the Japanese were able to break into the compound containing the dozen Japanese officers. One of the men attempting to reach that compound from Broadway was Ichiro Takata. A survivor of the breakout, he later described his experiences:

As I was running I was praying for a bullet in the body. I wanted to receive it as soon as possible. I could see in front of me my comrades were going down like dominoes. I kept feeling, the next one is me. We were being raked by a strong spray of bullets. People on my left and right were going down. I kept thinking, it’s coming. Then I did go down. I tried to stand and I couldn’t. My leg wouldn’t work. I was wounded. To try to invite more bullets, I stretched my head and shoulders up from the ground. But many people were running from behind, and they stepped on my back, squashing me down again. I felt that if things kept happening like that I would live through it and I didn’t want to. I had prepared a knife. I took it out of my pocket, opened my tunic button and plunged it in hard below my left nipple. The blood made my hands slippery, and it didn’t go in too deeply. So I pushed all of my weight on it, trying to get it to penetrate hard. Finally I felt it go all the way through, but it missed my heart. I tried to grind myself around the knife, in a mortar-and-pestle action. So much blood was coming out that I thought I had managed to do it. I shut my eyes quietly. The sounds of the guns were louder, and I was becoming satisfied that I would finally die. I could now avoid the shame of being a prisoner. Gradually I felt proud again to be a soldier of the Japanese Army.

By the time a ceasefire was called at 6.20am, the Australians had successfully rounded up about 500 men on a strip of land now littered with corpses. They still confronted the reality that the perimeter fence had been breached, and about 300 POWs had made good their escape into the surrounding countryside. It was assumed those escapees would be a grave threat to the population of Cowra and the surrounding region, though in reality the code of the Japanese soldier did not sanction violence against civilians. The soldiers on the patrols formed to hunt them down, however, were considered fair game.

Realising the bleakness of their situation, some of the escapees chose death by their own hands over recapture. One of them, an infantryman by the name of Shoichi Yamamoto, had managed to gain a rifle in the course of his escape. With no ammunition and no magazine, his outlook was hopeless. He attempted to take his own life, but was unsuccessful. He was recaptured but died later in hospital.

The first rounding up of those men who had escaped took place before daybreak. Many of the Japanese simply surrendered when tracked down by the patrols, which consisted largely of Australian soldiers, but also of policemen and civilians. The danger they faced was illustrated by the case of Harry Doncaster, bludgeoned and stoned to death by a group of Japanese, the third member of the Australian forces to lose his life. Three days later, a member of the Volunteer Defence Corps, having joined the hunt for escapees, suffered accidental but fatal gunshot wounds.

On the Japanese side, the toll was much higher. After a round-up that lasted nine days, 334 Japanese were recovered, including 25 who had died. Added to those killed during the breakout, the number of Japanese casualties reached 234. No-one had effected a successful escape.

Cowra Today

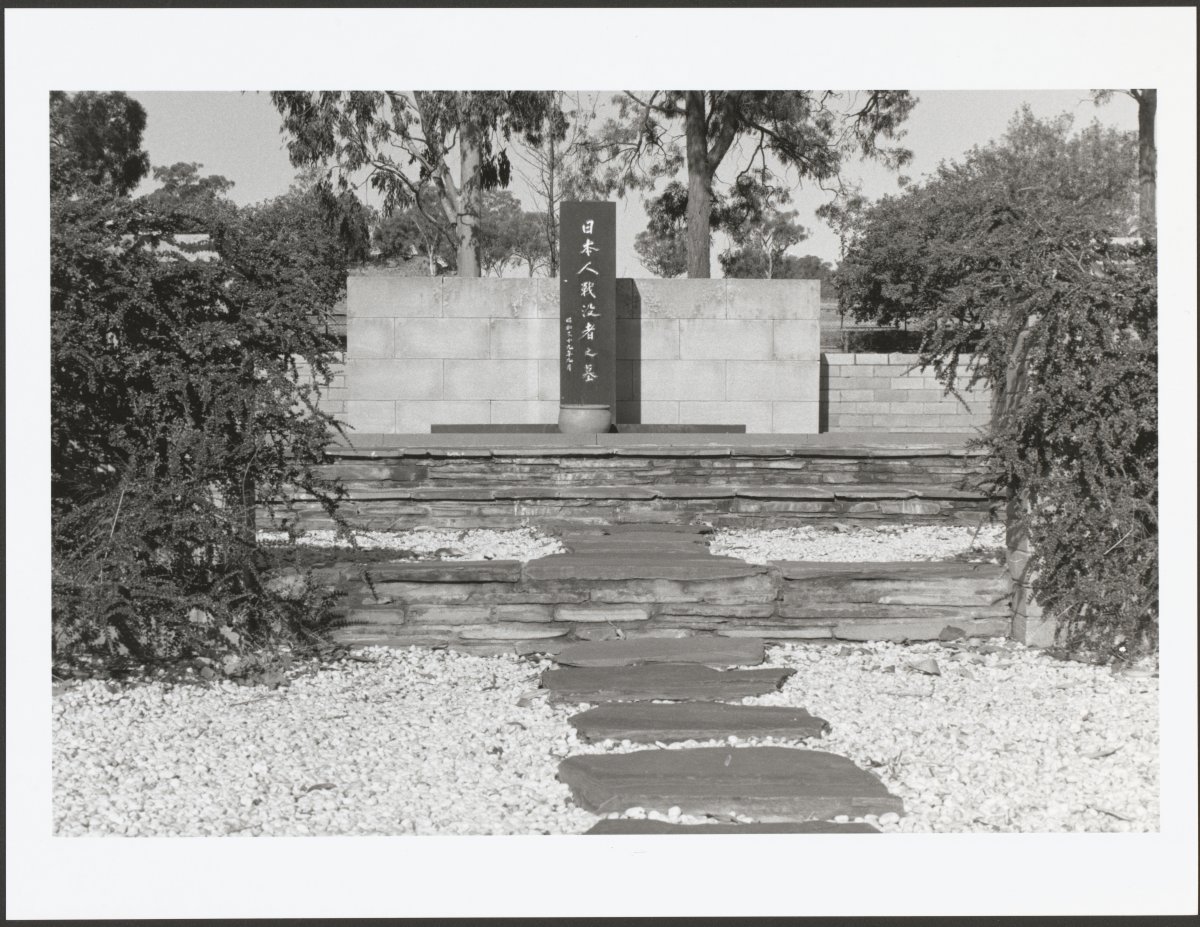

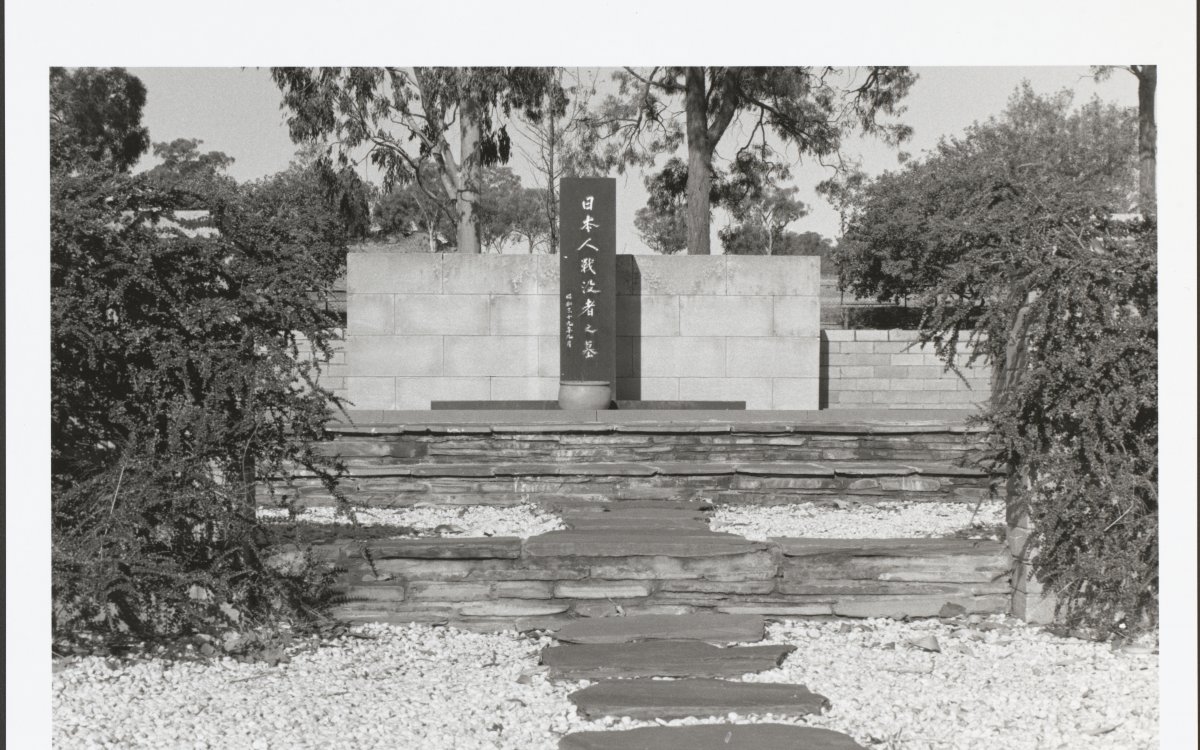

Kelson, Brendon, 1935-2022. (1996). Japanese War Cemetery, Doncaster Drive, Cowra [picture]. http://nla.gov.au/nla.obj-143115541

Kelson, Brendon, 1935-2022. (1996). Commonwealth War Graves Cemetery, Doncaster Drive, Cowra [picture]. http://nla.gov.au/nla.obj-143115643

Kelson, Brendon, 1935-2022. (1996). Memorial to Australian soldiers killed in 1944 POW outbreak (1994), Squire Park, Street, Cowra [picture]. http://nla.gov.au/nla.obj-143114945

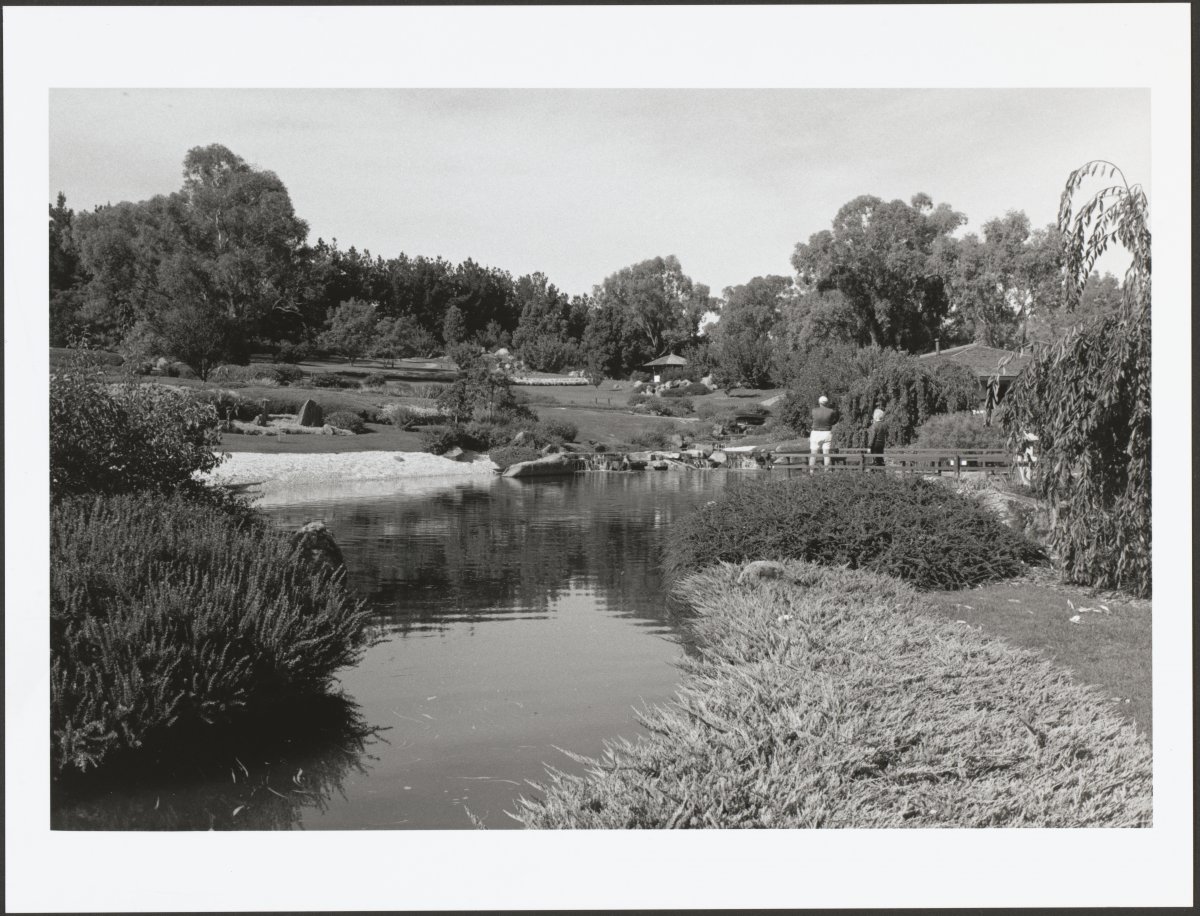

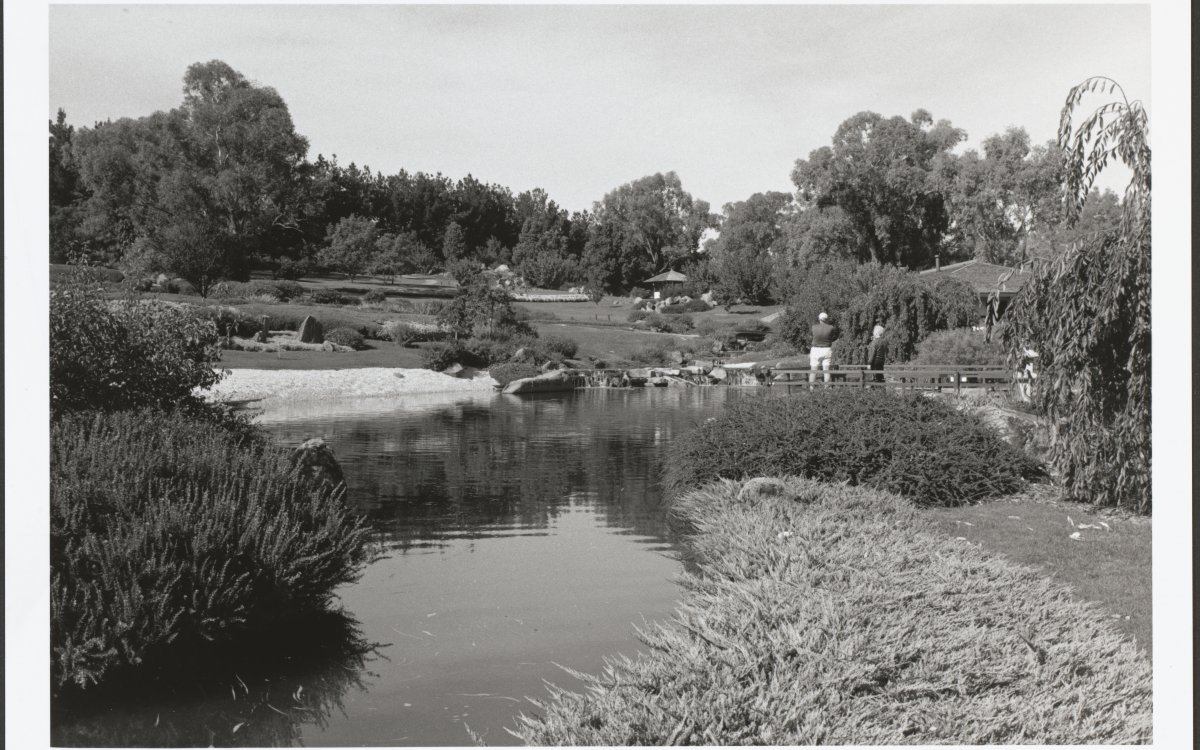

Kelson, Brendon, 1935-2022. (1996). Japanese Garden and Cultural Centre, Sakura Avenue, Cowra [picture]. http://nla.gov.au/nla.obj-143114246

Today, Cowra is home to a Japanese garden which attracts visitors to its annual Cherry Blossom Festival, Sakura Matsuri. The town is also the site of the only Japanese war cemetery in Australia. The cemetery was established in 1964 and holds the remains of all Japanese nationals who died on Australian soil during World War II, including those killed in the breakout attempt.

Nearby is the Australian War Cemetery while holds the remains of the four Australians killed during the breakout and other soldiers from Cowra and surrounds who died during the war. The town also has a memorial plaque remembering the Australian soldiers killed in the breakout.

Activities

- Cowra is a town in central western New South Wales, 300 kilometres inland from Sydney. Why do you think the decision was made to place a camp in this location? Find a map showing other sites of internment camps around Australia during World War II. Are there any similarities in terms of location?

- How might the announcement that some prisoners were to be transported cause stress and anxiety among the prisoners?

- As a resident of Cowra, how do you think you would have felt knowing there were going to be several thousand ‘enemies’ in a camp outside your town? What impact might this have had on the town and its people? Use Trove Newspapers to find articles relating to the Cowra breakout and aftermath.

- What can be inferred from the fact that Cowra is the site of a Japanese War Cemetery, where the remains and memory of the Japanese prisoners are looked after next to the Australian War Cemetery? Are there any other examples of former adversaries caring for the graves of the opposition? Is there any significance in this act?