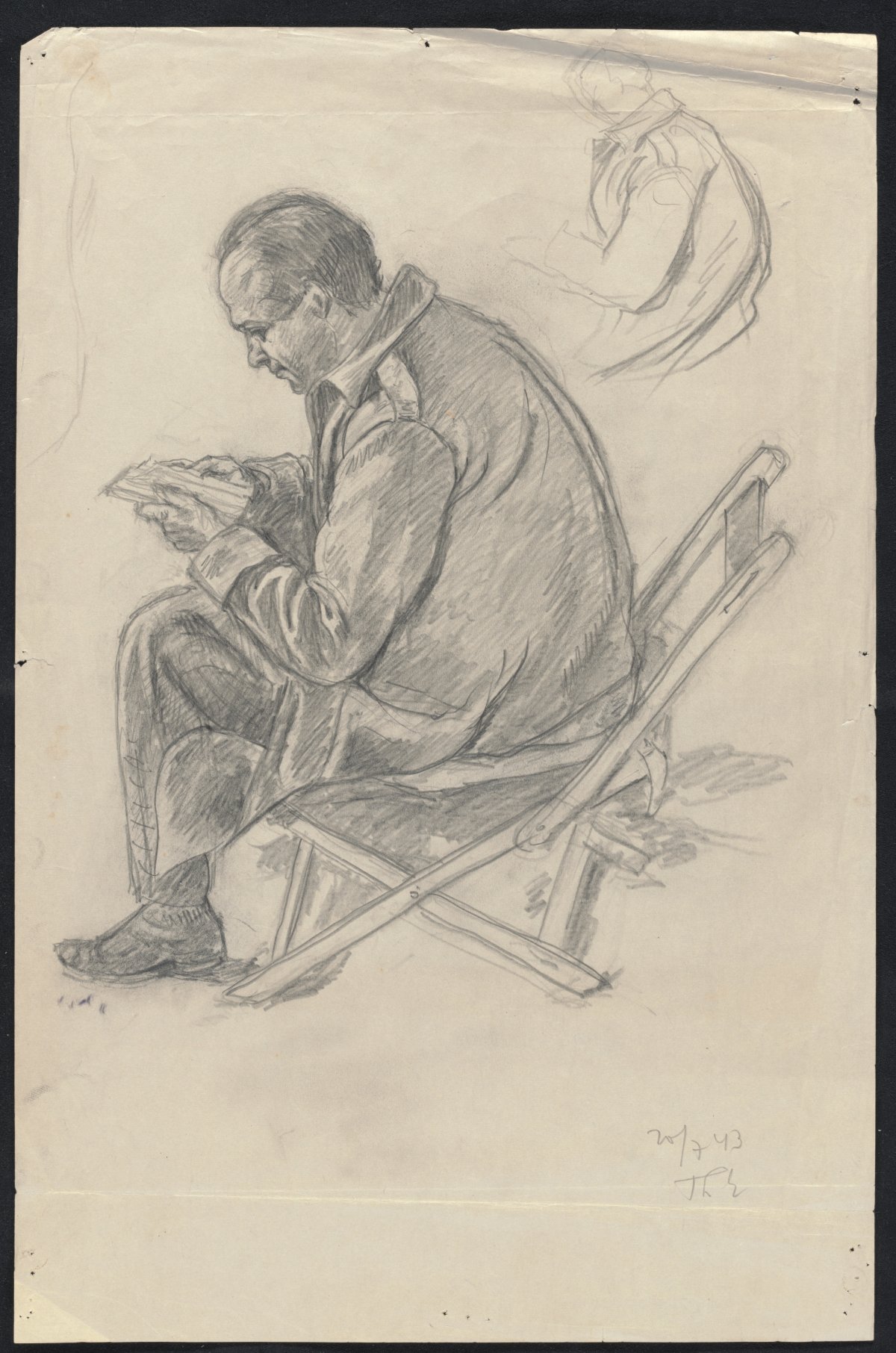

Engel, Theodor, 1886-1978. (1943). Study of a Dunera boy in a deck chair, 20 July 1943 / Theodor Engel. http://nla.gov.au/nla.obj-153000808

Enemy Aliens

In the years leading to the outbreak of World War II, Hitler and his government’s anti-Semitism became increasingly violent. German Jews sought refuge in Britain and other countries in increasing numbers; however, those who settled in Britain to escape persecution nevertheless found themselves labelled as ‘enemy aliens’ the moment war was declared between Germany and the United Kingdom.

This change in classification did not have much impact initially, as it was understood that they were refugees escaping from Nazi oppression; however, sentiment quickly changed once the Nazi forces claimed victories in the Low Countries and in France. Panic followed and the British Government ordered widespread arrests of ‘enemy aliens’. Among the German population resident in Britain were Nazi sympathisers, even potential ‘fifth columnists’ who might possibly have posed a threat to the British public. With rising tensions and anxieties both among the Government and the general public, internment policies were applied with no consideration given to faith, race or politics.

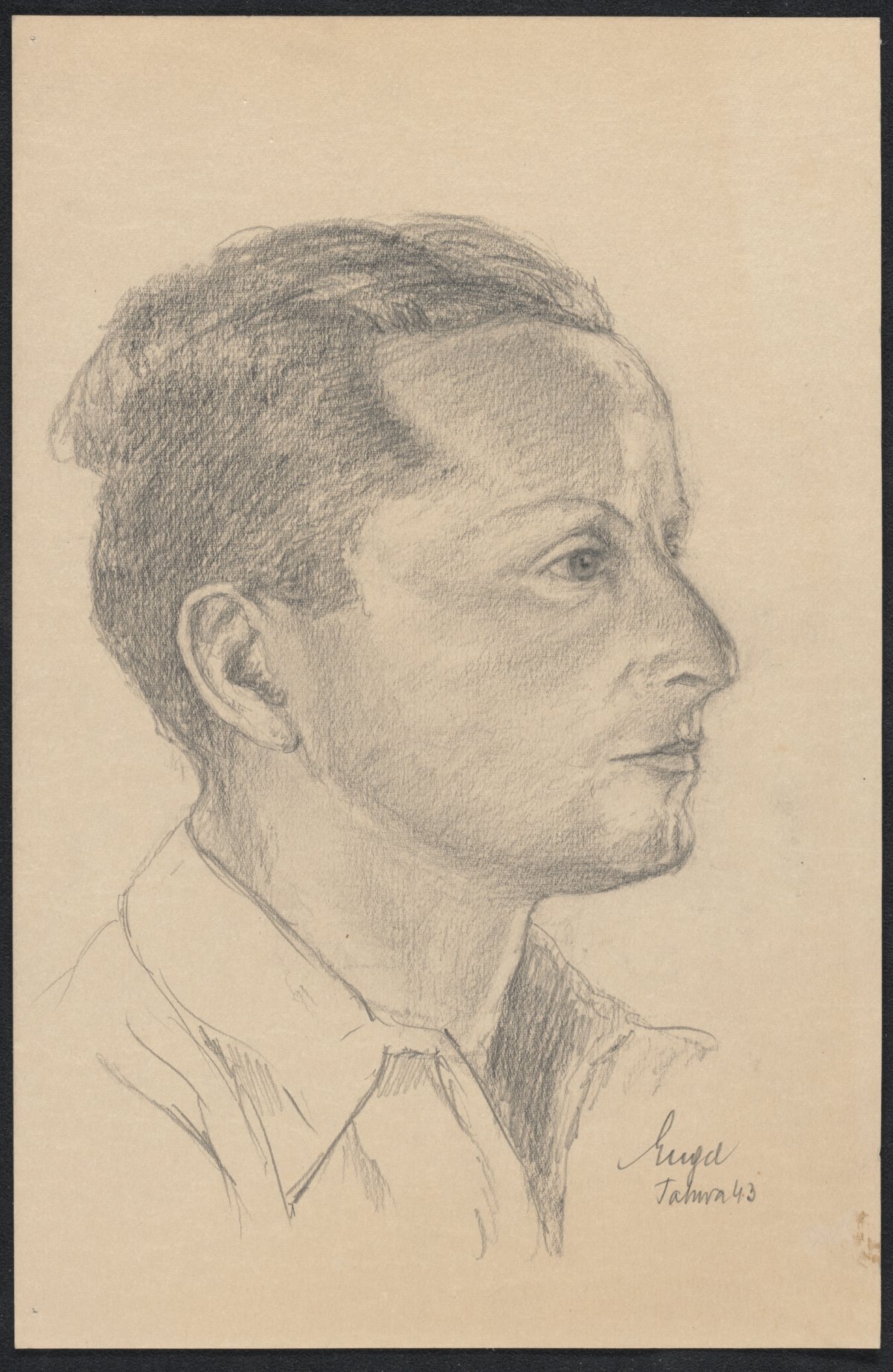

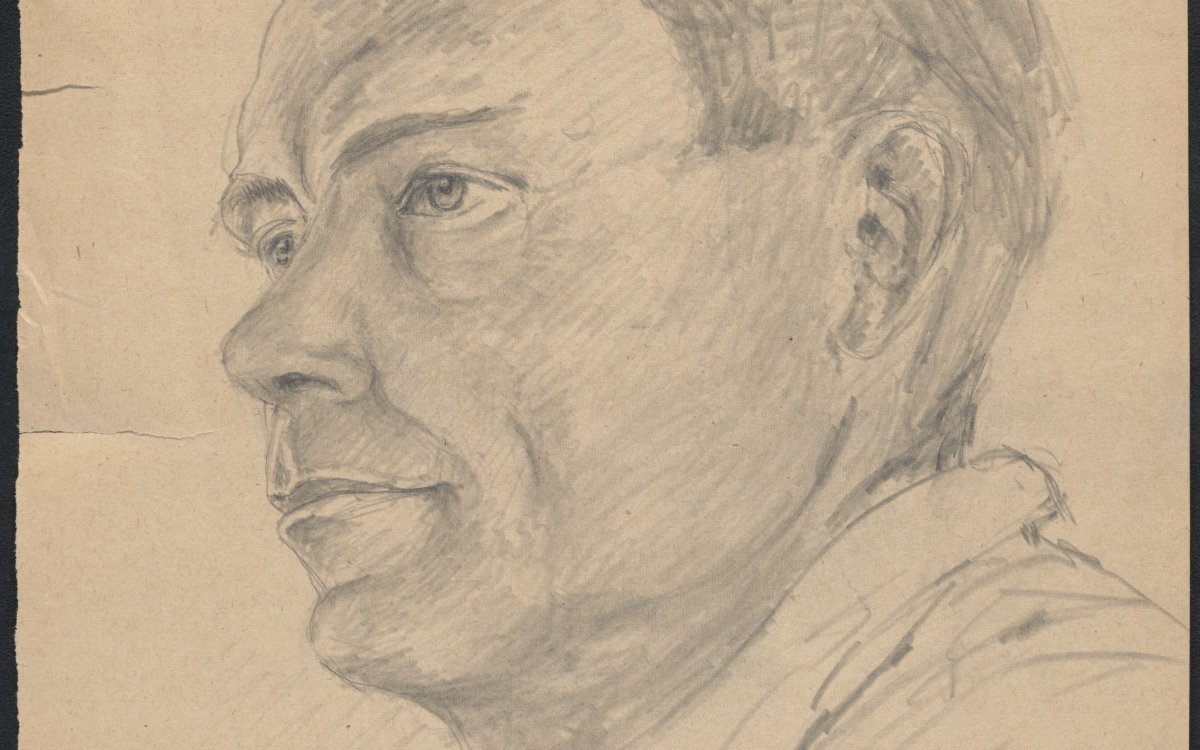

Engel, Theodor, 1886-1978. (1943). Study of a Dunera boy at Tatura, Victoria, 1943 / Theodor Engel. http://nla.gov.au/nla.obj-152997802

HMT Dunera

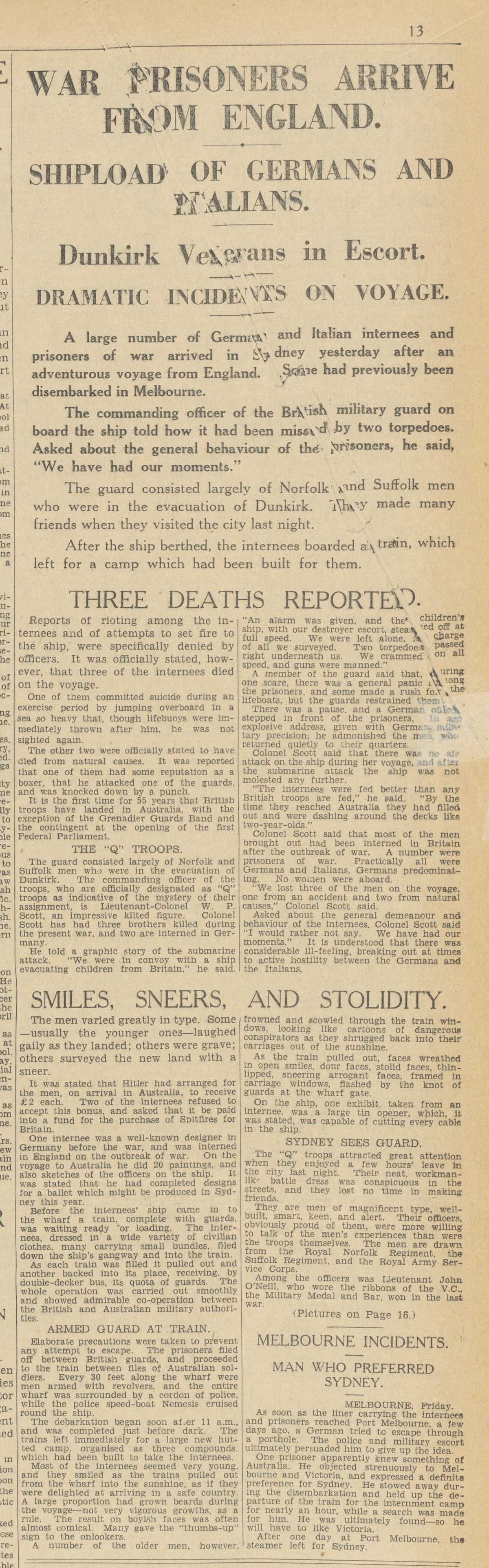

To ease the burden of a large and growing internee population, the British Government decided to send a portion of them to the dominions, including Australia. To accommodate this undertaking, the British Government conscripted passenger ships and other commercial vessels to provide troop transport to and from theatres of war. One of those ships was the SS Dunera (or HMT Dunera once in service). The Dunera’s job was to take 2,542 ‘enemy aliens’ to Australia. The majority—all together, 2,036 of them—were anti-Nazi and most of them were Jewish refugees from Germany and territories now under Nazi control. However, much like the internment policies of the time, transport of aliens was a broad sweep and the Dunera was also transporting 200 Italian and 251 German prisoners of war, along with a smaller number of Nazi sympathisers. Tensions were high among the ‘passengers’ and fights were commonplace. Around 300 British guards were assigned to the trip, but it was apparent to those on board that the guards were just as likely to perpetrate violence on the passengers.

The Dunera left Liverpool on 10 July 1940. The voyage quickly turned horrific. Before the war, Dunera was an ocean liner with a passenger capacity of 367 (103 first class, 100 second class, 163 third class) and 260 crew. With 2,542 prisoners and 300 crew the ship was dangerously overcrowded. Soap, toothpaste and toothbrushes were not given to the passengers for a great part of the voyage and disease was rampant. This did nothing to improve relations between passengers or between passengers and the guards. All this was happening in an environment in which the passengers and crew had to live with the constant threat of attacks by German U-boats.

In Fremantle, an Australian officer boarded the vessel and recorded his shock at what he saw:

Actually the position is this: All these internees … were dumped on the ship and told to get out to Australia, without any thought of documents or anything else. The whole show is terrible, if you could see these Huns and Dagos behind the wire after 2 months at sea, with rough weather all the way, you would wonder how on earth they survived it.

Although the ship was now in Australian waters, the experience did not improve for most of the passengers, who later became known as ‘the Dunera Boys’, until the ship reached Sydney and the remaining passengers were disembarked and loaded aboard a train for the 750km journey to their destination, the internment camp at Hay, New South Wales.

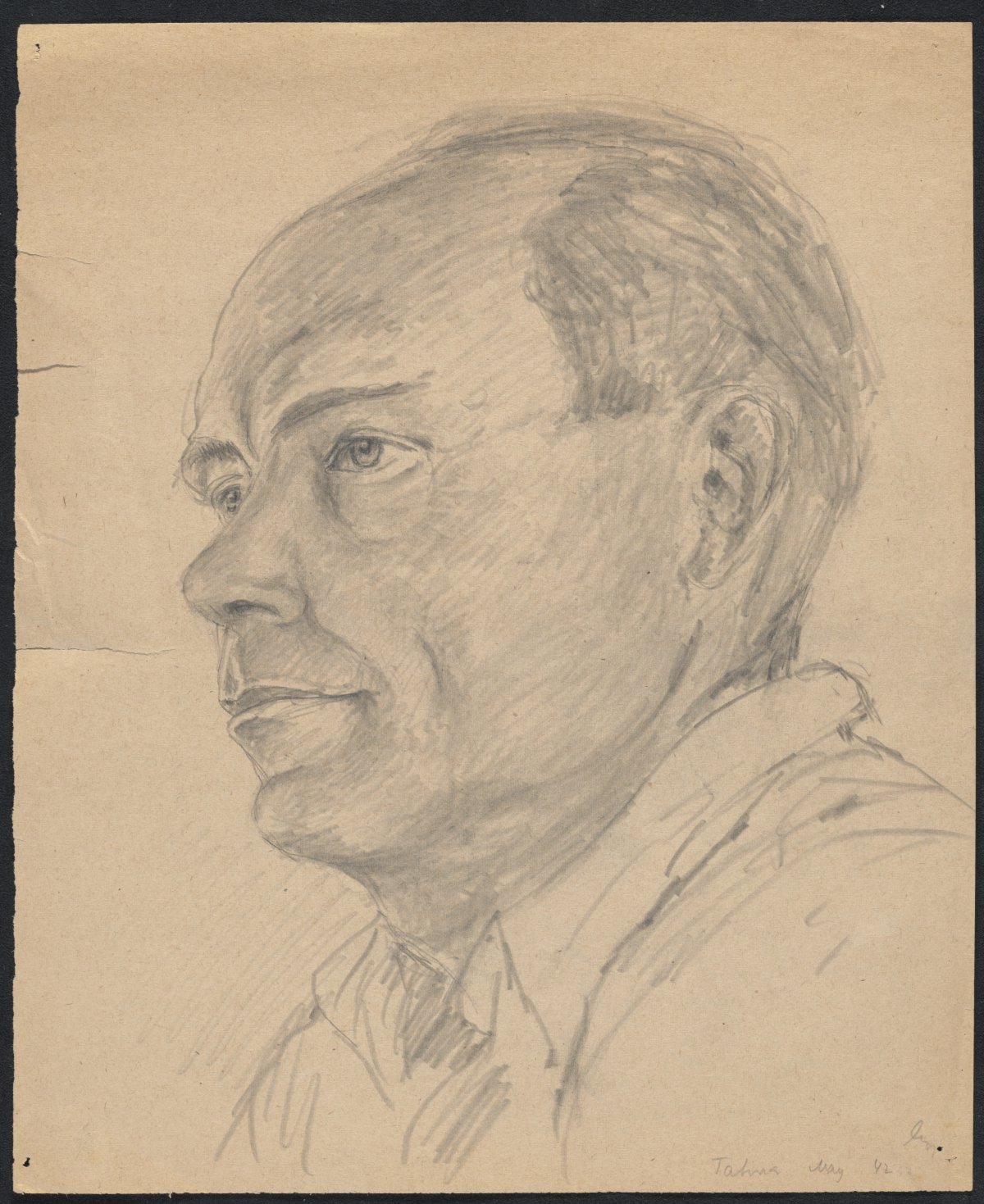

Engel, Theodor, 1886-1978. (1942). Study of Heinz, a Dunera boy at Tatura, Victoria, May, 1942 / Theodor Engel. http://nla.gov.au/nla.obj-152999452

WAR PRISONERS ARRIVE FROM ENGLAND. SHIPLOAD OF GERMANS AND ITALIANS. (1940, September 7). The Sydney Morning Herald (NSW : 1842 - 1954), p. 13. http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article27947256

Arrival in Australia

Eric Eckstein, one of those on board the ship as it docked in Sydney, recalled a noticeable change:

Once we were on the train everyone was friendly, especially the guards, who fascinated us with their slouch hats and their rolled cigarettes. Our guard, George, got tired of standing beside the door with his rifle and came to sit beside us to have what he called a ‘yarn’. George thought it was ‘bloody rotten’ to trick people like that, when he learned about the assurances that had been given to some of the older internees who had been separated from their families that they would accompany them in the same convoy. ‘Just hold my rifle a sec. while I roll myself a smoke.’ We were quite flabbergasted. It was totally unexpected and marvellously refreshing. George was the first person to appear genuinely interested in what had happened to us, and naturally he was overwhelmed with our complaints. All he could do was shake his head and say: ‘Well I never, the rotten bastards’.

The passengers loaded on the train had little idea of where they were going or what to expect in the unfamiliar landscape of western New South Wales.

One of the youngest members of the Dunera contingent, Walter Kaufmann, recalled his experience:

We travel into the darkness. The soldiers have long fallen silent, as have we; the wheels clatter monotonously, the rat-a-tat penetrates our half-sleep, and when at dawn the beat of the wheels stops, the train has rattled to a halt. In black on the grey station wall is emblazoned the word HAY, and along the platform soldiers stand in line, all of them younger than those on the train. They stand there watchfully, their slouch hats buckled tightly under their chins, and then a lieutenant gestures behind him with his thumb—he makes a bold impression with slouch hat and leather strap across his breast. ‘Okay, you men, come on out!’, we hear him call. The guards in the train pass on the order. We stir ourselves and climb out one after the other. Soon there is movement in our ranks. Flanked by the soldiers, we march from the station. Under a cloudless sky and scorching sun, in the middle of the column I trudge toward the watch-towers, recognizable in the distance. The lieutenant, who has ridden ahead on his brown stallion to disappear in a cloud of smoke, and calls to us in apparent derision: ‘Hot and dusty, too’.

The Italians aboard the Dunera had disembarked earlier in Melbourne, destined for internment in Victoria. Like the Germans, they too were anti-fascists, and some had been living in Britain for lengthy periods before being sent to the Antipodes. Loaded onto a train in Melbourne, Marco Gazzi recalled:

The sergeant came into our compartment and spoke to us and we all answered in English, and he said to us, ‘Ohrrr you speak better English than we do’. We were all Italian, but we all spoke with a different accent, Welsh, Scottish and London, and he said to us, ‘Do you all smoke?’ and he went off and bought a packet of Woodbine cigarettes, and gave us all one. I said, ‘You can give mine to one of the others—I don’t smoke’, and off he went and bought me a two ounce [60 gram] block of Nestlé’s chocolate. And my thought was: ‘If an Army Sergeant can do that for me, it must be a wonderful country.’

This warm experience was not universal. Italian passenger Vittorio Tolaini endured the Dunera voyage but was not interned at Hay. He was transported to the camp at Loveday in South Australia. There, he observed:

Our treatment in Camp 10 was very harsh. Bashed with the butts of rifles we were pushed into a large hall and forced to strip naked whilst the guards thoroughly examined each piece of clothing. Some of us were coerced to submit to an extremely degrading investigation. We were forced to bend forward while medical staff closely handled and explored the most intimate parts of our bodies to ensure that we didn’t have anything hidden there. It was a terrible experience.

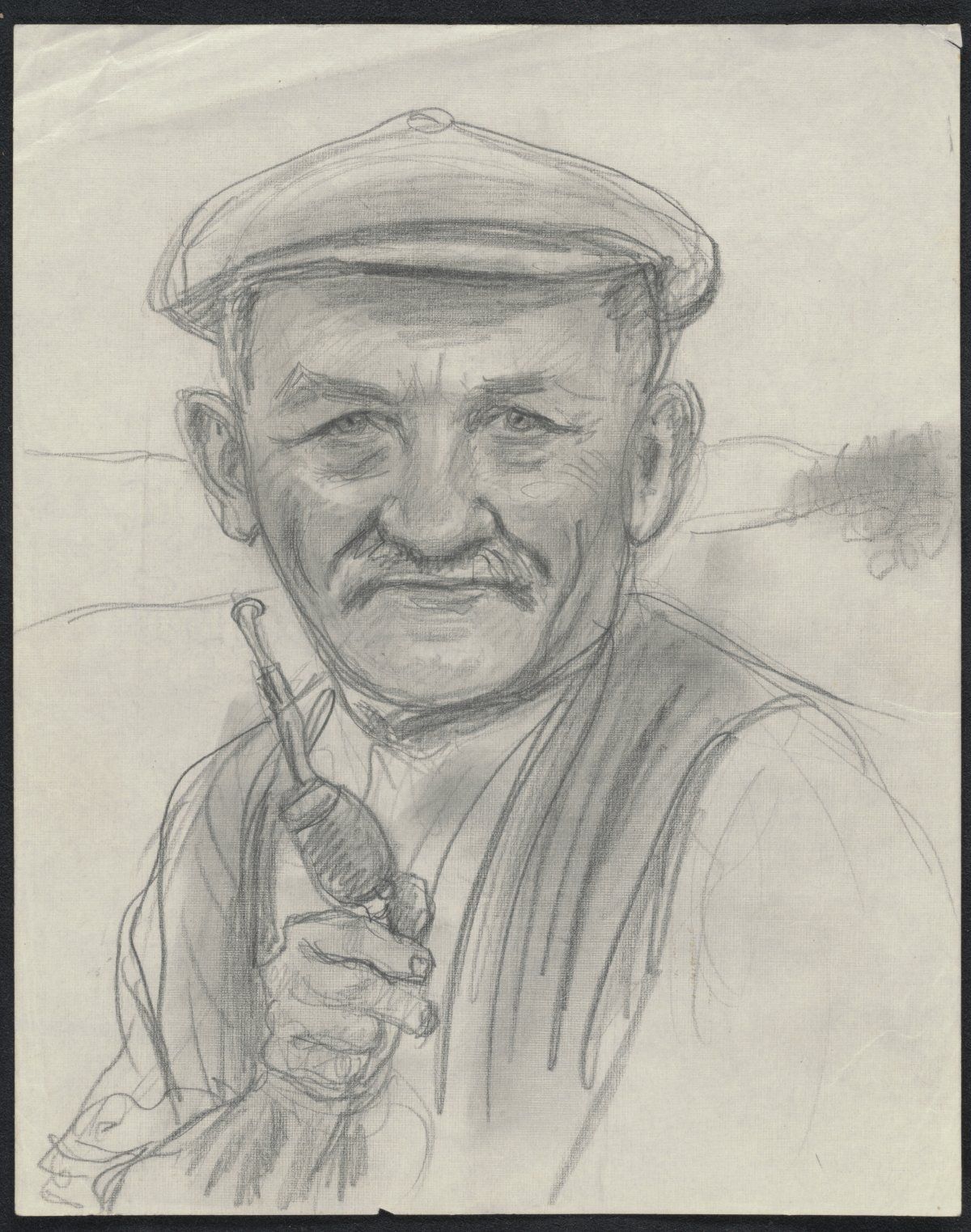

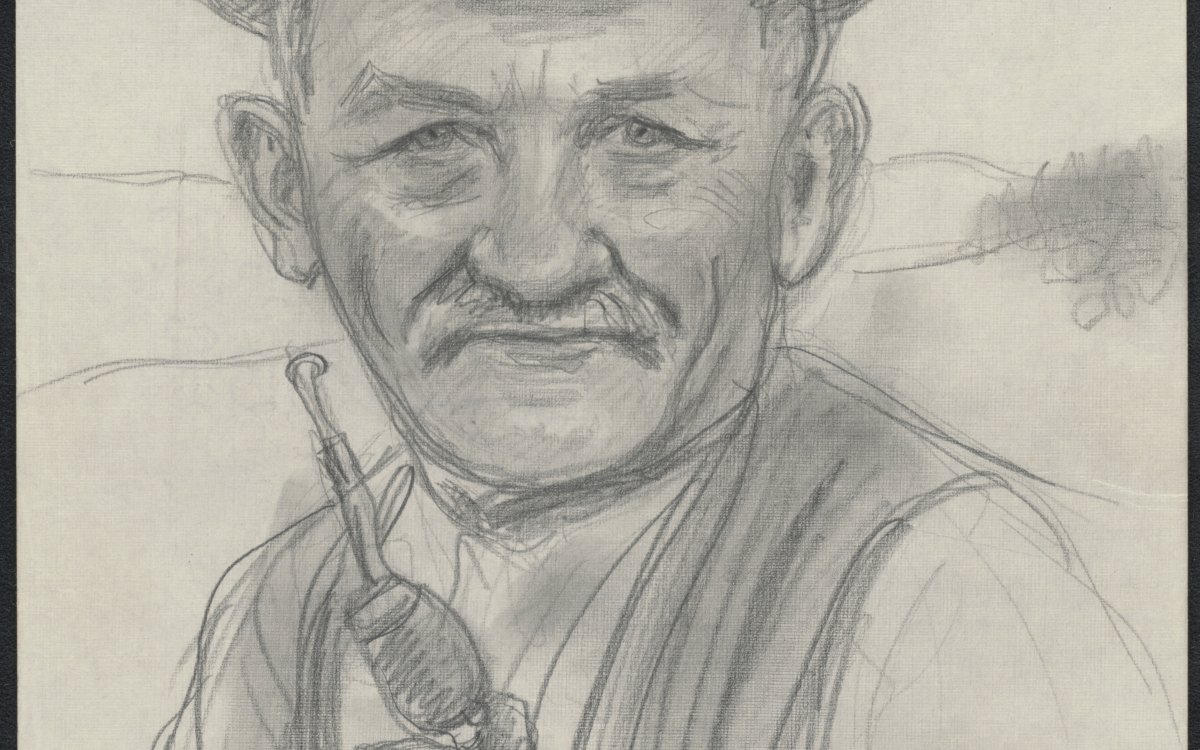

Engel, Theodor, 1886-1978. (1942). Study of a Dunera boy holding a pipe, 1942 / Theodor Engel. http://nla.gov.au/nla.obj-152997209

Aliens Distinguished

On 30 July 1941, the Australian Government announced that, should be required, it would agree to intern 300 male Japanese internees. Australia would eventually accommodate 3,160 Japanese who were transported to Australia from neighbouring countries under Allied control, including New Zealand, New Caledonia, the former New Hebrides (now Vanuatu) and the Dutch East Indies (now Indonesia).

At the outbreak of the war, 1,103 Japanese already residing in Australia were interned. These prisoners were soon outnumbered by those brought to Australia from elsewhere. As late as November 1946, the date of their final release, there were still 3,268 Japanese in Australian internment camps.

The Australian government, in time, recognised that this treatment of ‘aliens’ who were refugees from European persecution was unfair. From February 1942, the National Security Regulations distinguished clearly between ‘allied nationals’, ‘enemy aliens’, ‘neutral aliens’ and ‘refugee aliens’; however, the government remained firm in its resolve to detain Japanese people.

For the Dunera Boys and many like them, classification in the last of these categories brought release from internment. Commonly, these men then volunteered for service in the Australian armed forces. As Australian policy did not allow such men overseas on combat duties, many soon found themselves serving alongside more than 500 other Jewish refugees in the 8th Australian Employment Company, providing invaluable labour in support of the war effort. For them, at last there was an opportunity to fight fascism, and they eagerly embraced it.

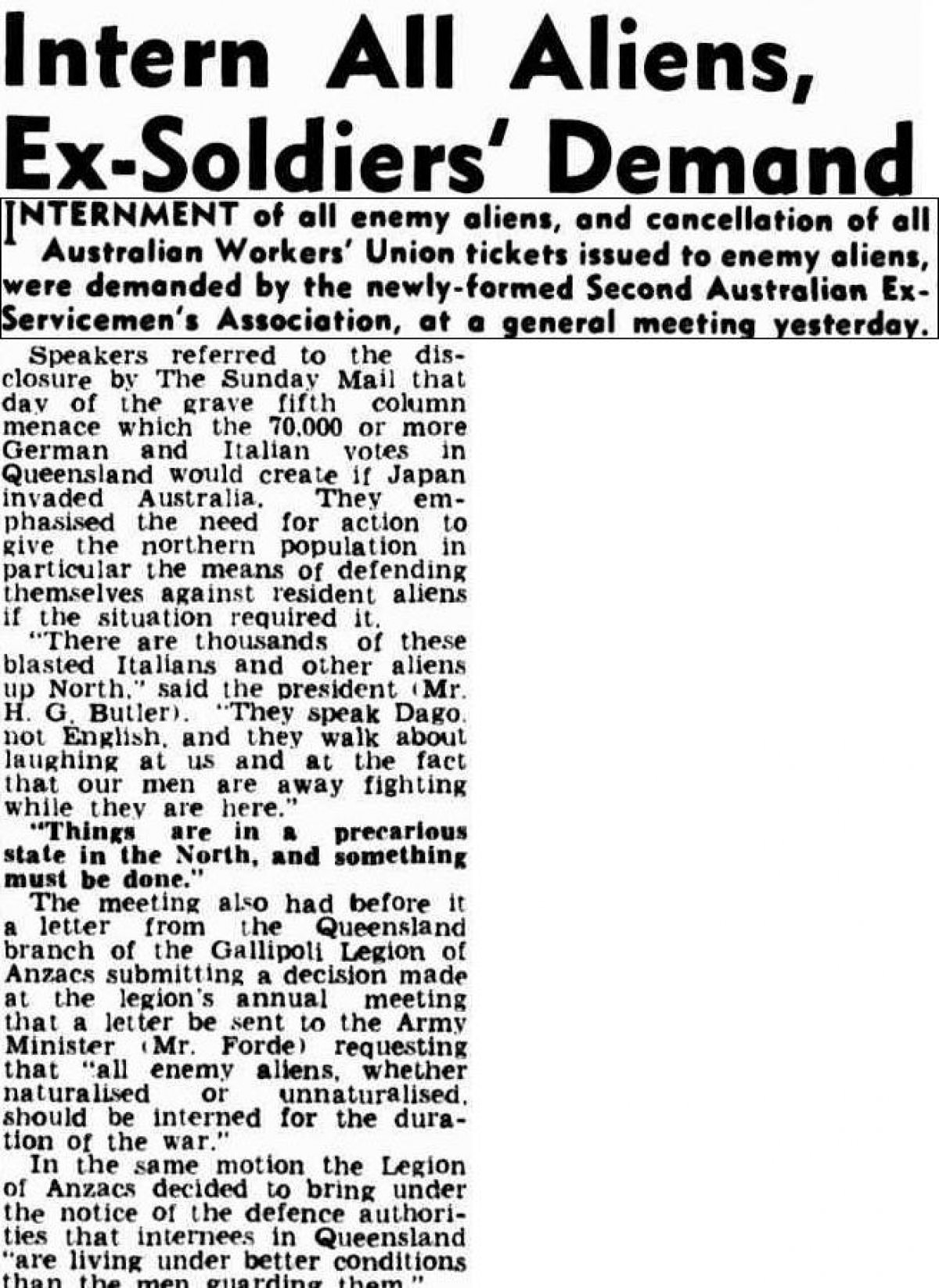

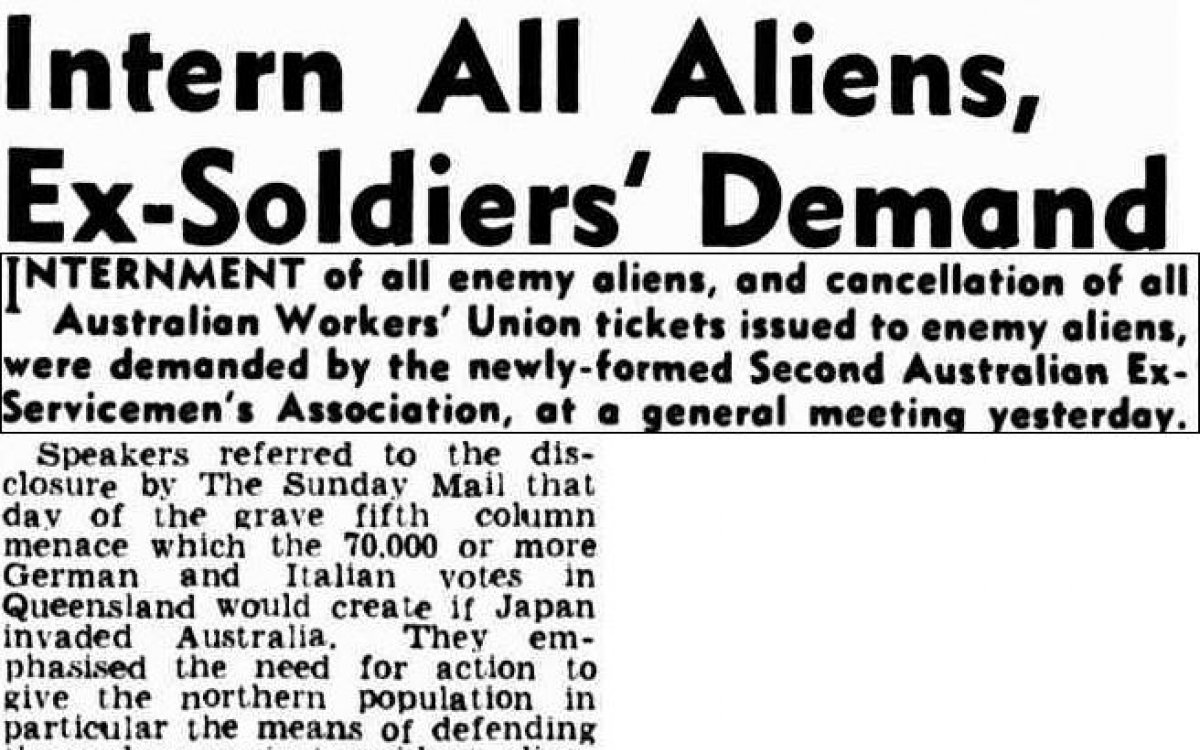

Not everyone was happy to have those designated as aliens released from internment, even if they were pitching in to the war effort. Ex-soldiers and people from communities across Australia called for the internment of all aliens regardless of status.

Intern All Aliens, Ex-Soldiers' Demand (1942, February 2). The Courier-Mail (Brisbane, Qld. : 1933 - 1954), p. 3. http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article50137810

After the war, the bond between the men who were interned at Hay and who had suffered on board the Dunera remained strong. Regular reunions were held with Dunera Boys coming from across the country to meet and reminisce.

Talbot, Henry, 1920-1999. (1963). Dunera Boys reunion, Melbourne, 1963 [picture] / Henry Talbot. http://nla.gov.au/nla.obj-143101197

Talbot, Henry, 1920-1999. (1981). Dunera Boys reunion, Melbourne, 1981 [picture] / Henry Talbot. http://nla.gov.au/nla.obj-143101740

Talbot, Henry, 1920-1999. (1987). Dunera Boys reunion, Sydney, 1987 [picture] / Henry Talbot. http://nla.gov.au/nla.obj-143101546

Talbot, Henry, 1920-1999. (1995). Dunera Boys reunion, Melbourne, 1995 [picture] / Henry Talbot. http://nla.gov.au/nla.obj-143101345

Activities

- Once war was declared and British prisons started to become overcrowded, the government of the time made the decision to transport prisoners to overseas territories. What similarities can you draw between this situation and earlier examples of prisoner transportation? Do these decisions say anything about the prevailing feelings of the British government at the time(s) towards its colonies or dominions? Discuss.

- After February 1942, distinctions were made among ‘enemy aliens’ based on the reasons for their internment, with those fleeing persecution and those from allied nations distinguished from prisoners of war, enemy sympathisers, etc. But some Australians still called for the imprisonment of all aliens. Why do you think there was still animosity towards these people? What justification could people make for imprisoning people fighting on the same side?

- Michael Brent, a Dunera Boy, was interviewed by the National Library of Australia’s Oral History and Folklore team. Listen to him talk about his voyage on the Dunera and his time in Hay. He begins talking about the Dunera from 1 hour and 7 minutes. Use this link to begin from that point. Use the subject headings to locate sections of interest.