This resource has been generously supported by the Embassy of the Kingdom of the Netherlands in Australia, to commemorate the 400th anniversary of the arrival of Dirk Hartog on the West Australian coast in 1616.

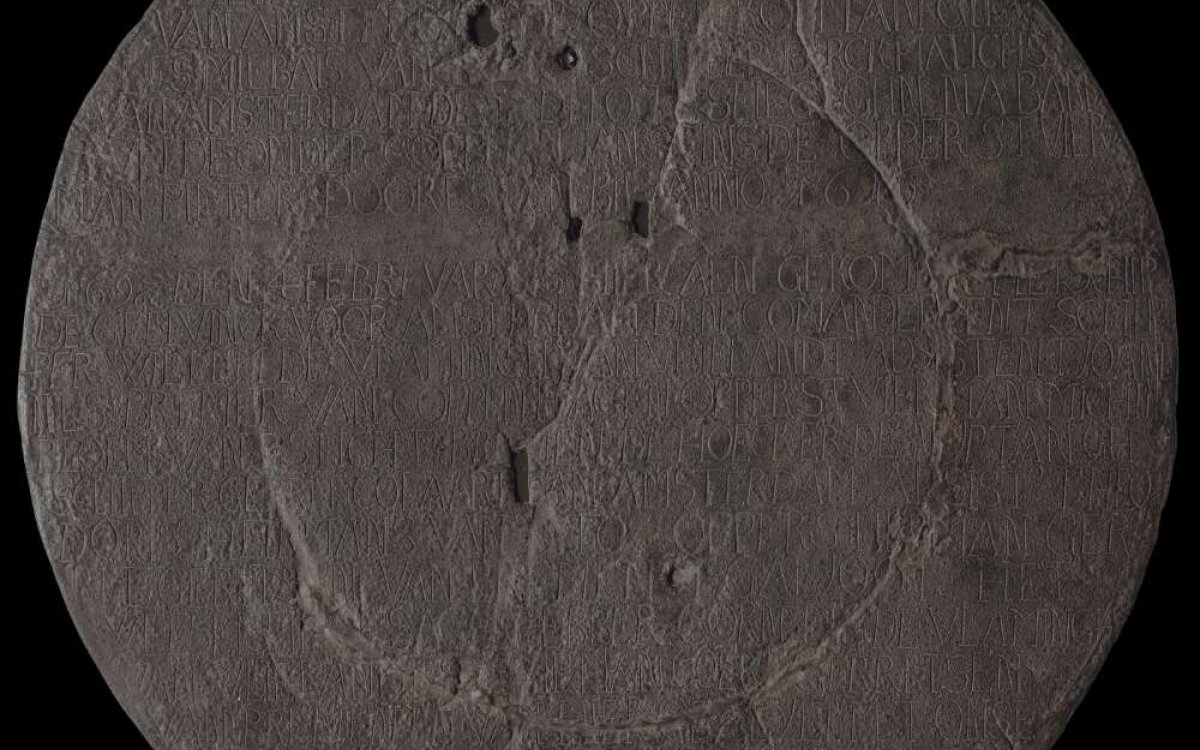

(1950). [Replica of the Vlamingh Plate] [realia]. http://nla.gov.au/nla.obj-135734827

As captain of the newly built Eendracht, Dirk Hartog was bound for the East Indies in 1616, along with other VOC ships. Separated from those ships in a storm, and seeking to shorten his sailing time to Batavia, Hartog used the strong winds of the ‘roaring forties’. Finding himself off course, Hartog made contact with the West Australian coast. This was the second time Europeans had landed on the continent of Australia.

Hartog spent three days exploring the area now known as Dirk Hartog Island. He declared the area inhospitable and of no use to the VOC in their quest for trading goods and world domination. Hartog recorded the existence of a large continent to the East and named this continent ‘Landt van d’Eendracht’after his ship. Flattening a pewter dinner plate, Hartog inscribed it with the details of his arrival. He nailed it to a post, in an area now known as Cape Inscription, and continued up the coast of Western Australia, charting the area for the first time before heading to Batavia.

The plate remained there, until 1697, when fellow Dutch Captain Willem de Vlamingh visited the island, finding the plate weathered and half-buried. He took the plate and replaced it with his own. On this new plate, Vlamingh copied the transcription left by Hartog, and added in the details of his own visit.

Vlamingh’s plate remained untouched until 1801, when two French ships, the Naturaliste led by Jacques Hamelin and the Géographe led by Nicolas Baudin, visited the island. Louis de Freycinet, a young cartographer of the French navy, removed Vlamingh’s plate, only to be ordered to return it by Captain Hamelin.

Later in 1818, when Freycinet was himself a captain of his own ship, the Uranie, he returned to Dirk Hartog Island and took the plate again. With no-one to order him to return it, he took his prize back to France. For some time, it sat unnoticed on a shelf among some copper plates at the Académie Française. It was discovered in 1940, in storage in the Musée de l’Homme in Paris, and returned to Australia by the French Government.

The National Library of Australia’s collection includes this replica plate of the original Vlamingh plate, which is now stored in the collection of the Western Australian Maritime Museum.

As captain of the newly built Eendracht, Dirk Hartog was bound for the East Indies in 1616, along with other VOC ships. Separated from those ships in a storm, and seeking to shorten his sailing time to Batavia, Hartog used the strong winds of the ‘roaring forties’. Finding himself off course, Hartog made contact with the West Australian coast. This was the second time Europeans had landed on the continent of Australia.

Hartog spent three days exploring the area now known as Dirk Hartog Island. He declared the area inhospitable and of no use to the VOC in their quest for trading goods and world domination. Hartog recorded the existence of a large continent to the East and named this continent ‘Landt van d’Eendracht’after his ship. Flattening a pewter dinner plate, Hartog inscribed it with the details of his arrival. He nailed it to a post, in an area now known as Cape Inscription, and continued up the coast of Western Australia, charting the area for the first time before heading to Batavia.

The plate remained there, until 1697, when fellow Dutch Captain Willem de Vlamingh visited the island, finding the plate weathered and half-buried. He took the plate and replaced it with his own. On this new plate, Vlamingh copied the transcription left by Hartog, and added in the details of his own visit.

Vlamingh’s plate remained untouched until 1801, when two French ships, the Naturaliste led by Jacques Hamelin and the Géographe led by Nicolas Baudin, visited the island. Louis de Freycinet, a young cartographer of the French navy, removed Vlamingh’s plate, only to be ordered to return it by Captain Hamelin.

Later in 1818, when Freycinet was himself a captain of his own ship, the Uranie, he returned to Dirk Hartog Island and took the plate again. With no-one to order him to return it, he took his prize back to France. For some time, it sat unnoticed on a shelf among some copper plates at the Académie Française. It was discovered in 1940, in storage in the Musée de l’Homme in Paris, and returned to Australia by the French Government.

The National Library of Australia’s collection includes this replica plate of the original Vlamingh plate, which is now stored in the collection of the Western Australian Maritime Museum.

1. Have students create a timeline of the many visits that were made to Dirk Hartog Island between 1606 and 1818. Have them consider:

- How many visitors were there to Shark Bay in the 212 years between 1606 and 1818?

- What nationalities were represented on those visits?

- Did any of the visitors make a claim to the land? Why or why not?

- Who did the land belong to?

2. Show students the original plate held in the Rijksmuseum, and the replica of the Vlamingh plate held in the National Library of Australia.

Tell them that Hartog chose to use pewter to record his visit to the Western Australian coast. Have them investigate:

- What is pewter?

- What purposes did it have in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries?

- Why do you think Hartog used pewter?

- Why do you think Hartog left the plate?

- What did he write on the plate?

- What did Vlamingh write on his plate?

- What are the differences between the two plates?

3. 2016 is an important year in Australian history, marking 400 years since the arrival of Dirk Hartog in Western Australia. Have students investigate what special events are planned to commemorate this anniversary. In doing so, have them ask:

- What are the planned celebrations in 2016?

- What name do we give to a 400 year anniversary?

- How has Dirk Hartog Island changed in those 400 years?

- What are the future plans for Dirk Hartog Island and why?

4. Have students imagine that they are the first explorers on a newly discovered planet. Having arrived in a previously uncharted area, they are going to leave their mark on history with an object or long-lasting record for posterity. Have them think about the following:

- What will you need to consider in terms of where you leave your object?

- What should you think about in terms of the conditions on that planet?

- What material are you going to use and why?

- What information are you going to include and why?

- What are the reasons for leaving behind a record of your visit?

Ask students to illustrate their object, including any writing or markings on it, and display their work in the classroom.

5. Have students look closely at these two maps created by Vlamingh when he visited the West Australian coast in 1697. These maps were so accurate that Matthew Flinders used them to complete his own map of Australia in 1814.

Links here:

http://nla.gov.au/nla.obj-231306558/view

http://nla.gov.au/nla.obj-231306393/view

Ask them to find the relevant areas on Google Maps.

Investigate the Vlamingh maps with the following questions:

- Are the maps accurate? Why or why not?

- What challenges do you think Dutch explorers faced when charting new territories?

- Why did Vlamingh call the island near Perth, ‘Rottnest’?

- Where exactly did Vlamingh explore?

- Why was Vlamingh visiting the West Australian coast?

6. Students can then look at Freycinet’s map of the Shark Bay area, from his first visit in 1803 and an image from his 1818 visit to the same area.

Links here:

http://nla.gov.au/nla.obj-230976159/view

http://nla.gov.au/nla.obj-135928443/view

Use the images as inspiration for a larger enquiry about Freycinet’s visits to the area. Ask students to investigate the images with the following questions:

- What did Freycinet find there in 1803?

- What did he find there in 1818?

- What did he do with what he found? Why do you think he did that?

- What did Freycinet call the land that he was visiting? Who does he reference on the map?

- What appears to be happening in the scene with the local Indigenous people?

- What happened on Freycinet’s voyage back to France?

- He took something else on that voyage, which was out of the ordinary – can you find out more?

7. Have students write a narrative from the point of view of the Indigenous people in the 1818 Freycinet image. Have them consider their feelings about the encounter and what was exchanged.

8. Dirk Hartog left a legacy behind him—not only a pewter plate, but a destination for future ships from other countries, such as France and England. In 1772, the first French vessel visited Dirk Hartog Island.

Have students research the journey of Frenchman François de Saint Aloüarn, including his claim of the western half of Australia for France, and his death on his return voyage. Conduct a debate in your classroom on the topic: ‘Western Australia actually belongs to the French’. You should encourage your students to consider the viewpoints of all groups with interest in Australia—the Indigenous people, the English, the French and the Dutch.

9. Hartog’s original plate now resides in the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam as the earliest artefact of European visitation to Australia. The original Vlamingh plate is held at the Western Australian Maritime Museum; however, this wasn’t always the case. The Vlamingh plate has moved from Australia to France, and back to Australia.

Using TROVE, have students research the story of the Vlamingh plate, and its return to Australia from France in the 1940s. In searching for newspaper articles about the event, have students consider the following questions:

- What should govern where an item of such significance is held?

- What was the reasoning given by Western Australia for being the rightful owners of the Vlamingh plate?

- What was given to the National Library in exchange for the plate?

- Where do you think the plate should be held and why?

Other Digital Classroom sources that relate to the concepts explored in this source include: Indigenous Experiences and Early Explorers.