This resource has been generously supported by the Embassy of the Kingdom of the Netherlands in Australia, to commemorate the 400th anniversary of the arrival of Dirk Hartog on the West Australian coast in 1616.

At least four VOC ships were shipwrecked on the Western Australian coast in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. The Batavia in 1629, the Vergulde Draeck in 1656, the Zuytdorp in 1712 and the Zeewijk in 1727. Other shipwrecks may still be found, as many ships went missing between the Netherlands and the East Indies in the 200 years of the VOC’s power.

The tragedy of the Batavia shipwreck is one of the most gruesome tales to be found in Australian history. On its maiden voyage and loaded with a cargo of coins and valuable antiquities, the Batavia left Texel for the East Indies, with a fleet of seven ships. In command of the voyage was merchant Francisco Pelsaert, with Ariaen Jacobszoon as Captain and Jeronimus Cornelisz third in command. Due to a violent storm, the Batavia was separated from the fleet.

Most of the 300 or more people on board were male officers and soldiers. Several civilian passengers were onboard, including women and children voyaging to the East Indies as family of VOC employees.

Once at sea, Jacobszoon and Cornelisz plotted to mutiny so they could use the ship for piracy. Before they could carry out their plan, the Batavia was shipwrecked off the coast of Western Australia at the Abrolhos Islands, near Geraldton.

Some passengers drowned; 180 survivors, including women and children, were transferred to nearby islands on the ship’s boats along with provisions. Cornelisz and 70-odd men remained on the wreck.

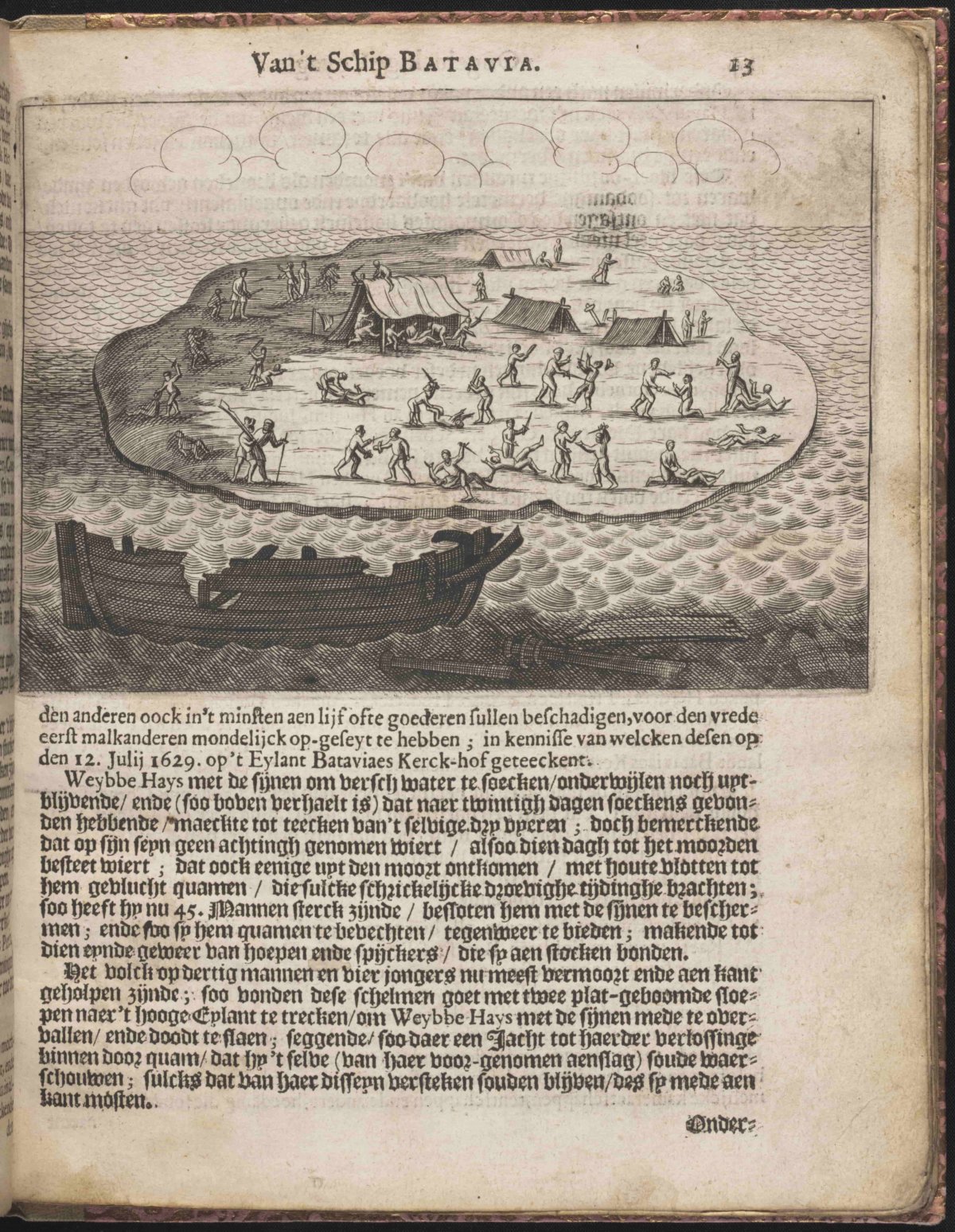

With no water source and limited supplies, Pelsaert left the survivors and headed to Batavia in search of help, inciting much bitterness among those who remained. In his absence, Cornelisz took control of the disgruntled men, set about dividing up the group on the pretence of searching for water and supplies, and then embarked on a raping and slaughtering campaign of the remaining survivors.

Having reached Batavia, Pelsaert returned in a rescue ship to a scene of debauchery, blood and terror. Cornelisz was captured, his hands were cut off and then he was executed on Seal Island. The remaining culprits were punished and taken back to Batavia, where they were later executed. The treasures of the ship were lost to the sea until the wreck’s discovery in 1963.

Captain Francisco Pelsaert’s published journal about the Ongeluckige Voyagie (or ‘Unlucky Voyage’) reveals the horrors in dramatic illustrated detail. The National Library of Australia’s copy is the uncommon Utrecht edition, which included not only new illustrations such as this image, but additional eye-witness accounts from wreck survivors.

Pelsaert, Francisco, -1630. (1649). Ongeluckige voyagie van't schip Batavia na Oost-Indien uyt-gevaren onder de E. Franç̧ois Pelsaert : gebleven op de Abriolhos van Frederick Houtman op de hooghte van 28 en een half graden by Zuyden de Linie Equinoctiael : vervattende 't verongelucken des schips, en de grouwelijcke moorderyen onder 't scheeps-volck, op't eylandt Bataviaes Kerck-hoff nevens de straffe der handtdadigers in de Jaren 1628 en 1629 ; hier achter is by- gevoeght eenige discourssen der Oost-Indische Zee-vaert als mede de gantsche gelegentheyt der Koopmanschappen diemen in Indien doet. t' Utrecht : Lucas de Vries, Boeck-verkooper in de Snipper-vlucht http://nla.gov.au/nla.obj-39984464

1. Once familiar with the events of 1629, have students explore the story of the Batavia wreck in detail with the following questions:

- Who were the main characters on board the Batavia and what was the relationship between them?

- What were the factors that led to a plan of mutiny against Pelsaert?

- Is any one person to blame for the events of 1629?

2. Have students work together to create a timeline of the events that happened in 1629, from the departure of the Batavia in Texel, to the trials of the mutineers in Batavia.

Show students the images in Pelsaert’s journal, and allocate these images to their timeline. Have them each choose an event from the remainder of the timeline, and have them illustrate this scene.

Combine their own illustrations with the images from Pelsaert’s journal, in a visual timeline on the classroom wall.

3. Explore the other three known VOC shipwrecks with your students - the Vergulde Draeck (or Gilted Dragon) in 1656, the Zuytdorp in 1712 and the Zeewijk in 1727. In building an understanding of the need to preserve history, lead the class in a discussion with the following questions:

- Who owns a shipwreck?

- Should a wreck site be preserved?

- Should a wreck site be visited?

4. Have students view the episode, Batavia Shipwreck Ruins from the series Australia’s Heritage – National Treasures with Chris Taylor.

The need to preserve wreck sites on the Western Australian coast inspired the forming of an organisation known as ANCODS, the Australian Netherlands Committee on Old Dutch Shipwrecks. This organisation is tasked with preserving a collection of thousands of items belonging to those wrecks, some of which are displayed in museums around the world.

Using Trove, have students research the salvaging of the wrecks off the Western Australian coast, including the discovery of artefacts and graves in the Abrolhos Islands. They should consider the following questions:

- What has been discovered in the shipwrecks?

- Where are those items kept now and why?

- Who is responsible for preserving such artefacts?

Using Pinterest, students can then create a theme wall of links to the many existing artefacts, memorials, statues and sites that tell the story of the Batavia. They should write appropriate descriptions for each item, with regards to historical accuracy.

5. Survivors of shipwrecks on the WA coast may have lived with the local indigenous people and not only survived, but reproduced. Using both Trove and the Internet, have students investigate current theories, evidence and projects, in relation to indigenous people with Dutch heritage.

Other Digital Classroom sources that relate to the concepts explored in this source include: Early Explorers.